London Underground electric locomotives

Electric locomotives were first used on the London Underground when the first deep-level tube line, the City and South London Railway (C&SLR), was opened in 1890. The first underground railways in London, the Metropolitan Railway (MR) and the District Railway (DR), used specially built steam locomotives to haul their trains through shallow tunnels which had many ventilation openings to allow steam and smoke to clear from the tunnels. It was impractical to use steam locomotives in the small unvented tubular tunnels of the deep-level lines, and the only options were rope haulage (as on the Glasgow Underground) or electric locomotives.

| London Underground electric locomotives | |

|---|---|

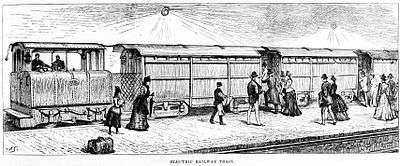

A print from the Illustrated London News showing a City & South London Railway electric locomotive and train | |

| Stock type | Deep-level tube |

| Notes | |

The C&SLR was opened just a few years after the very first use of electricity to drive rail vehicles (trains or trams) and the primitive locomotives reflected this. Over the next 15 years, motors became smaller, gear drives and motor suspension were developed and reliable multiple unit control became available. Electric multiple unit trains became the standard, but electric locomotives were still being built.

From 1903, the MR and the DR began to electrify the central parts of their lines for use by electric multiple units (EMUs). On both railways carriages were hauled by electric locomotives that were exchanged for a steam engine to run over un-electrified distant sections. The last steam-hauled passenger trains were replaced in 1961.

When not hauling passenger trains, the electric locomotives were used for shunting and for hauling departmental trains. Some locomotives, as on the MR, were retained just for these duties. Rather than buy additional locomotive for this work, as was required with the battery-electric locomotives, makeshift locomotives were created from withdrawn passenger vehicles of at least three types, which were modified to haul trains over any part of the system or shunt rolling stock at Acton Works.

City & South London Railway

| Central & South London Railway locomotives | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

C&SLR locomotive number 13, preserved at the London Transport Museum Depot, 2005 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

When the City & South London Railway (C&SLR) was authorised in 1884, it was intended to be a cable-hauled line, but during the construction phase, the promoters decided to use electric traction, despite the fact that the technology was in its infancy.[1] Two prototype locomotives were built by Mather & Platt in 1889, to a design by Dr Edward Hopkinson, with Beyer-Peacock supplying many of the mechanical parts. No. 1 used motors mounted directly on the drive axles, while No. 2 had motors driven through gears. Trials were conducted in December 1889 with No. 1 and two passenger cars. No. 2 was also used for testing, but it is not clear whether it pulled any cars. A production run of 14 locomotives was then built, numbered 1 to 14, duplicating the original numbers 1 and 2. Each had four wheels, with Edison-Hopkinson motors fitted to the axles, which were permanently wired in series. A 26-step rheostat was used to control the speed, and a switch which altered the connections to the armature was used to reverse the direction of travel.[2]

The locomotives were small and short to fit within the small diameter tunnels, which were 10 feet 2 inches (3.10 m) at the northern end of the railway, and 10 feet 6 inches (3.20 m) on the straighter southern section, to allow higher speeds.[3] The cab was built along the centre line of the locomotive with a door at each end and the controls and equipment mounted on the sides. There was a single driving position at one end of the locomotive with the power controller on one side and the Westinghouse air-brake valve and hand-brake column on the other. The controls worked directly so no form of multiple-unit control was ever possible.

Each locomotive could haul three coaches at up to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) on good track, providing a service speed of around 11.5 mph (18.5 km/h). At the end of a run, the arriving locomotive was trapped in the platform by its carriages. A replacement locomotive hauled the train away on the next trip and the released locomotive was then available to head the next incoming train (this is called "slip working").[2]

The train air-braking system, controlled by the driver, was fed from an air reservoir on the locomotive and, as the original locomotives were unable to generate their own compressed air, the reservoirs were recharged at Stockwell Station from an air line maintained at 80 psi (5.5 bar).[2] Later, locomotives were fitted with compressors.

The railway was opened on 4 November 1890 by The Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) and locomotive No. 10 carried a commemorative nameplate with the name Princess of Wales to celebrate its use on that occasion. There was soon a need for an additional two locomotives to operate the service. Nos. 15 and 16 were built by Siemens with a modified design of motor,[4] which attempted to overcome the problem of burnt-out armatures that had plagued the line since its opening.

In 1895, the C&SLR itself built locomotive No. 17 at Stockwell depot, and carried out a series of tests on locomotives 12, 15 and 17, as more locomotives would soon be needed for the extensions being made. They ordered three more locomotives from different manufacturers in 1898, which were equipped with four-pole motors, a more efficient control system using series-parallel switching of the motors, and on-board compressors. The motors were still mounted on the axles. Another two locomotives (Nos. 21 and 22), which were built at Stockwell Depot, included further refinements and were the prototypes for the final batches of locomotives. Nos. 23 to 52 were built by Crompton to an improved design, including nose-suspended motors connected to the axles by a single reduction gear, but still bore a strong external resemblance to the original locomotives. Between 1904 and 1907, locomotives Nos. 3 to 12 were rebuilt with new electrical equipment to improve their performance.[5]

Following the introduction of new locomotives and the abandonment of the restrictive King William Street terminus in 1900, the C&SLR was able to run trains with four cars.[6] Five-car trains were introduced from 1907.[7] Six-carriage trains were briefly operated in 1914/15 and from October 1923[8] before the last part of the line was closed for reconstruction and tunnel enlargement in November 1923.[9]

The enlarged tunnels allowed the locomotive hauled trains to be replaced by 'Standard' Stock electrical multiple units. 44 locomotives were in use just before the closure and some remained in service until 1925 hauling works trains while the tunnels were being enlarged.[7]

One locomotive survives in preservation. It was originally displayed as No.1, but investigations over a number of years finally identified it as either No. 13 or 14, and suggested that it was more likely to be No. 13 (the number which it now carries). After being displayed in the Science Museum,[7] it was transferred to the Acton store of the London Transport Museum, and then to the newly reopened museum in Covent Garden. No. 36 was displayed on a plinth at Moorgate Metropolitan line station for many years but was damaged beyond repair by a bomb in 1940. Some of its electrical parts were presented to Crompton Parkinson before the rest of it was scrapped.[7] A motor and axle from No. 36 are now held by the Science Museum but are currently in store.

Central London Railway

| Central London Railway locomotives | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

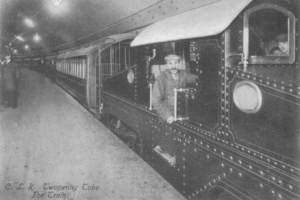

Original CLR locomotive with gate stock carriages behind | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Opened in 1900, the Central London Railway initially used 44-ton Bo-Bo electric locomotives to haul its trains. These long, low locomotives had deep plate frames, a central cab and equipment compartments on front and rear. The cabs had four doors, one on each side and one on each end (for safe access/exit when in the tunnels). Each axle carried a 117 hp (87 kW) GE56A motor directly mounted on it. When starting, pairs of motors were connected in parallel, and the two pairs were connected in series. The controller had nine series notches, after which the motors were open-circuited, reconnected in full parallel, and the controller had another seven parallel notches. The direct-working controls did not allow the locomotives to work in multiple.[10]

A serious design fault in these locomotives was their very high unsprung weight of 33 tons. Geared motors had not been used as it was thought they would be noisy in the confines of a tunnel. This resulted in serious problems with noise and vibration. Complaints from local residents started immediately after the service commenced and were such that the Board of Trade imposed a speed limit until modifications could be made. This was achieved by only using series mode on the controller, but by 1901, three of the locomotives had been rebuilt with new bogies and nose-suspended GE55 motors, reducing the unsprung weight to 11 tons.[11]

Six and seven car trains were run, and as on the City and South London Railway, locomotives were stepped back at the termini. A seven-car train required a crew of eight. Two men rode in the locomotive, there was a front and rear guard, and four additional men operated the gates on the passenger cars. 28 locomotives were built, although 32 were ordered, the remaining four intended for when the extension from Bank to Liverpool Street was opened. However, from 1901 trials were conducted with multiple units, with motor cars converted from trailer cars 54, 81, 84 and 88. These became the first operational multiple units in Europe, and the benefits of virtually eliminating vibration and the ease of reversing them at the termini resulted in an order for 64 motor cars being placed. They were delivered in mid-1903, and the locomotives became redundant after only three years.[12]

The three geared locomotives were retained, to be used for shunting at Wood Lane Depot, while the rest were offered for sale. The Metropolitan Railway subsequently bought two of the three, in order to carry out experiments in regenerative control. No. 12 remained at Wood Lane, becoming L21 in 1929. It saw occasional use until 4 May 1940, when the Central line was converted from three-rail to four-rail operation, and was scrapped in 1942.[13]

Metropolitan Railway

.jpg)

Metropolitan Railway electric locomotives were used on London's Metropolitan Railway with conventional carriage stock. On the outer suburban routes an electric locomotive was used at the Baker Street end that was exchanged for a steam locomotive en route.[14]

The first ten had a central cab and were known as camel-backs, and these entered service in 1906. A year later another ten units with a box design and a driving position both ends arrived.[14] These were replaced by more powerful units in the early 1920s.[15]

One locomotive is preserved as a static display at London Transport Museum[16] and another, No. 12 "Sarah Siddons", has been used for heritage events, most recently in 2019.[17]

District Railway

In 1905 the District Railway bought ten bogie box cab locomotives that looked similar to their multiple units, but were only 25 feet (7.6 m) long. They were manufactured by the Metropolitan Amalgamated Carriage and Wagon Company, and most of them had a single cab at one end. Consequently, they were worked in pairs, coupled back to back with the cabs at the outer end.[18]

The locomotives were used to haul London and North Western Railway passenger trains on the electrified section of the Outer Circle route between Earl's Court and Mansion House. In December 1908 these services terminated at Earl's Court[19] and the locomotives were used to haul District line trains, one coupled to each end of a rake of four trailer cars.[20] From 1910 trains from the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway (LT&SR) were extended over the District line, the steam locomotives being exchanged for electric ones at Barking.[21] Two rakes of carriages were provided by the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway, and were hauled over the District tracks by the locomotives working in pairs. Not needed, three locomotives were scrapped, leaving three pairs and one spare. Originally numbered 1A to 10A, those that were not scrapped became L1 to L7 after 1910.[18]

Their electrical equipment was reused on new multiple unit trains that were being introduced.

The locomotives were equipped for working in multiple. Each locomotive had four GE69 motors,[20] rated at 200 horsepower (150 kW) totaling 800 hp.[22] In 1922 the motors were replaced with GE260 surplus from the F Stock.[20] L2 and L7 were scrapped in 1938, and the remaining locomotives were scrapped in 1939,[23] after the LT&SR service was withdrawn. Their electrical equipment was re-used in F-stock cars which were being converted to air-door operation.[18]

Acton Works Shunters

For moving rolling stock around the main workshops at Acton, four electric locomotives were created out of withdrawn passenger vehicles.

- L10 - This Bo-Bo locomotive was built from two Hampstead Gate Stock driving motors. It was constructed at Acton Works in 1930 from cars 1 and 3, originally built in 1907 by the American Car and Foundry Company. The motor ends of both cars were joined back-to-back, and this design was the first of several similar vehicles constructed from old stock. The vehicle was fitted with adjustable couplers at each end, which could be raised or lowered to cope with tube stock or sub-surface stock. Because of the layout of Acton Works, only the couplings on the southern end, known as the "Acton" end (as opposed to the "Ealing" end), were used, and those at the Ealing end were gradually cannibalised for spares for the Acton end. It was subsequently rebuilt, with flat panels on the sides, rather than the louvred ones of the Hampstead stock, and lost its distinctive clerestory roof. The GE69 motors were replaced with the superior GE212 motors, which included interpoles and roller bearings.[24] It survived until 1978, when it was cut up on site by Cashmores.[25]

- L11 - Built in 1964 from two 1931 Standard Stock vehicles (numbers 3080 and 3109), this vehicle followed the same concept as L10, as both donor vehicles had some of their passenger compartments cut off and the two cabs and control sections were joined back to back. The resulting locomotive was a single vehicle Bo-Bo. A small section of the passenger compartment remained, and most of the air system and braking equipment was moved into it from beneath the frames, so that it could be more easily maintained. The vehicle had four WT54A motors, which were wired so that each pair remained permanently in series. Thus they worked at half voltage, but the slow-speed characteristics were better-suited for shunting. Dual couplings for tube and sub-surface stock were fitted at the Acton end only. The front door was blocked off, but had a low-level screen, to enable the driver to see the couplings more easily. When first built, it carried a maroon livery, but was painted yellow in 1983.[24] It saw use until the early 1990s and since preservation in 2004, has been on display outside Epping Underground station.[26]

- L13A/B - Created in 1974, this locomotive consisted of two 1938 Stock Driving Motor cars coupled back to back. Modifications included the addition of high level air pipes to allow coupling to other Departmental vehicles, reciprocating compressors, and the addition of power lines between the two cars. These gave the locomotive a very long shoegear span, since all four bogies were fitted with shoe beams, enabling it to cross gaps in the current rail at very low speeds. The locomotive was built so that L14A/B, which had proved the usefulness of a long shunting locomotive, could be scrapped.[27]

- L14A/B - Two of the flat fronted 1935 stock prototype cars were rebuilt to create this locomotive. The donor cars, numbers 10011 and 11011, had been displaced from the Epping - Ongar shuttle in 1966. They were transferred to Acton Works for articulation experiments, thought being given at the time to the articulation of trains on the Northern line.[27] The trailing ends of the two motor cars were cut back so there was only one window behind the rear double doors,[28] and both were mounted on a single steel bogie. The outer bogies were replaced with new lightweight ones, constructed of aluminium, and the unit was ready for testing to begin in August 1970. After a year of trials, engineers had collected sufficient data, and as it was never intended for the vehicle to enter passenger service, it was transferred to Acton Works as a shunting locomotive, where it was particularly useful, as the shoes spanned 64 feet (20 m). The experimental lightweight aluminium motor bogies were removed in 1975, and fitted to 1972 MkII car No3363, so that long-term testing of the design could be carried out. This ended the life of LT's only articulated locomotive, which was scrapped at Acton later that year.[27]

References

- Bruce 1988, pp. 9–10

- Bruce 1988, p. 11

- Bruce 1988, p. 7

- Bruce 1988, p. 12

- Bruce 1988, pp. 12–13

- Bruce 1988, p. 15

- Bruce 1988, p. 16

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 30.

- Day & Reed 2010, pp. 90–91.

- Bruce 1988, p. 25

- Bruce 1988, pp. 25–26

- Bruce 1988, pp. 27–29

- Bruce 1987, p. 18

- Green 1987, p. 26.

- Bruce 1983, p. 58.

- "Metropolitan Railway electric locomotive No. 5, "John Hampden", 1922". ltmcollection.org. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- "Past Events — Metro-land Heritage Vehicle Outing" (Press release). London Transport Museum. 11 September 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Bruce 1987, p. 19.

- Horne 2006, p. 44.

- Bruce 1983, p. 41.

- Bruce 1983, p. 47.

- "District Electric Trains" (PDF). Underground News. October 2010. p. 567.

- Bruce 1987, p. 89.

- Bruce 1987, pp. 20–21

- Bruce 1987, p. 90

- "L11 - A Unique Electric Locomotive". Cravens Heritage Trains. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Bruce 1987, p. 25

- Connor 1989, p. 89

Bibliography

- Croome, D.; Jackson, A (1993). Rails Through The Clay — A History Of London's Tube Railways (2nd ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-151-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, J Graeme (1983) [1970]. Steam to Silver: A history of London Transport Surface Rolling Stock. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 0-904711-45-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, J Graeme (1987). Workhorses of the London Underground. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 0-904711-87-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, J Graeme (1988). The London Underground Tube Stock. Shepperton: Ian Allan and London Transport Museum. ISBN 0-7110-1707-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Connor, Piers (1989). The 1938 Tube Stock. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-115-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2010) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (11th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-341-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Oliver (1987). The London Underground — An illustrated history. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1720-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2006). The District Line. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-292-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holman, Printz P. (1990). Amazing Electric Tube. London Transport Museum. ISBN 978-1-871829-01-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Institution of Civil Engineers Published Proceedings, Electrical Railways: The City & South London Railway, Edward Hopkinson - 1893

- Institution of Electrical Engineers Published Proceedings, Electrical Locomotives in Practice, P V McMahon - 1899 & The City & South London Railway, P V McMahon - 1904

External links

City & South London Railway

- Dr Edward Hopkinson, designer of the C&SLR's first locomotives

- Interior of locomotive No. 1, circa 1890-1900

- Locomotive No. 6, circa 1906-10

- Locomotive No. 36, 1925

- Locomotive No. 47, 1922

Central London Railway

Metropolitan Railway

- 1905 locomotive No. 1, circa 1920

- 1921 locomotive No. 2, circa 1921-7

- 1921 locomotive No. 15 with side panels removed, 1924

- 1921 locomotive No. 12, "Sarah Siddons", 1973

District Railway

Acton Works