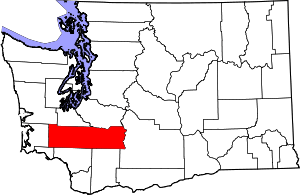

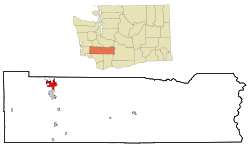

Centralia, Washington

Centralia (/sɛnˈtreɪliə/) is a city in Lewis County, Washington, United States. It is located along Interstate 5 near the midpoint between Seattle and Portland, Oregon. The city had a population of 16,336 at the 2010 census. Centralia is twinned with Chehalis, located to the south near the confluence of the Chehalis and Newaukum rivers.

Centralia | |

|---|---|

Centralia Downtown Historic District | |

Location of Centralia, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°43′14″N 122°57′41″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Lewis |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.81 sq mi (20.22 km2) |

| • Land | 7.62 sq mi (19.74 km2) |

| • Water | 0.19 sq mi (0.48 km2) |

| Elevation | 187 ft (57 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 16,336 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 17,745 |

| • Density | 2,328.43/sq mi (899.04/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98531 |

| Area code(s) | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-11160 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1503899[4] |

| Website | CityofCentralia.com |

History

In the 1850s and 1860s, Centralia's Borst Home, at the confluence of the Chehalis and Skookumchuck Rivers, was the site of a toll ferry, and the halfway stopping point for stagecoaches operating between Kalama, Washington and Tacoma. In 1850, J. G. Cochran and his wife Anna were led there via the Oregon Trail by their adopted son, George Washington, a free African-American. The family feared Washington would be forced into slavery if they stayed in Missouri after the passage of the Compromise of 1850. Cochran filed a donation land claim near the Borst Home in 1852 and was able to sell his claim to Washington for $6,000 because unlike the neighboring Oregon Territory, there was no restriction against passing legal ownership of land to African Americans in the newly formed Washington Territory.

Upon hearing of the imminent arrival of the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) in 1872, Washington and his wife, Mary Jane, filed a plat for the town of Centerville, naming the streets after biblical references and offering lots for $10 each, with one lot free to buyers who built houses. Washington also donated land for a city park, a cemetery, and a Baptist church.[5] Responding to new settlers' concern about a town in Klickitat County with the same name, the town was renamed Centralia by 1883, as suggested by a recent settler from Centralia, Illinois, and officially incorporated on February 3, 1886.[6] The town's population boomed, then collapsed in the Panic of 1893, when the NP went bankrupt; entire city blocks were offered for as little as $50 with no takers. Washington (despite facing racial prejudice from some newcomers) made personal loans and forgave debt to keep the town afloat until the economy stabilized; the city then boomed again based on the coal, lumber and dairying industries. When Washington died in 1905, all businesses in the town closed, and 5,000 mourners attended his funeral.

The boom lasted until November 11, 1919, when the infamous Centralia Massacre occurred. Spurred on by local lumber barons, American Legionnaires (many of whom had returned from WWI to find their jobs filled by pro-union members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)), used the Armistice Day parade to attack the IWW hall. Marching with loaded weapons, the Legionnaires broke from the parade and stormed the hall in an effort to bust union organizing efforts by what was seen to be a Bolshevik-inspired labor movement. Though it remains a point of controversy as to who fired first, IWW workers including recently returned WWI veteran Wesley Everest, stood their ground, engaging and killing four Legionnaires. Everest was captured, jailed and then brutally lynched. Other IWW members were also jailed. The event made international headlines, and coupled with similar actions in Everett, Washington and other lumber towns, stifled the American labor movement until the economic devastation of the 1930s Great Depression changed opinions about labor organizations.[7]

The town's name was originally a reference to the town's location as the midway point between Tacoma and Kalama (which were originally the NP's Washington termini), but proved to have longevity when it became the midpoint between Seattle and Portland, Oregon as well during the development of Washington's I-5 portion of the Interstate Highway System. As extractive industries faced decline, Centralia's development refocused on freeway oriented food, lodging, retail and tourism, as well as regional shipping and warehousing facilities, leading to 60 percent growth in population over the past four decades.

Economy and employment

Founded as a railroad town, Centralia's economy was originally dependent on such extractive industries as coal, lumber and agriculture. At one time, five railroad lines crossed in Centralia, including the Union Pacific Railroad, Northern Pacific Railway, Milwaukee Road, Great Northern Railroad and a short line.

The construction of Interstate 5 and its predecessor, U.S. Route 99, made Centralia the halfway point for motorists traveling between Seattle and Portland.[8]

The explosion of Mt. St. Helens on May 18, 1980 devastated the local lumber industry, as 12 million board feet of stockpiled lumber and 4 billion board feet of salable timber was damaged or destroyed.[9] Unemployment surged to double digits, and the town lost most of its retail base.

In 1988, London Fog opened the first factory outlet store in the Northwest, choosing the location because it was the midpoint between major northwest cities. Their success spawned the region's first factory outlet center, creating a tourist shopping destination. This led in turn to the redevelopment of the vintage downtown marketplace as an antique, art and specialty store destination.

On November 28, 2006, it was announced that TransAlta Corp., the largest employer in Centralia and operator of the Centralia Coal Mine and Centralia Power Plant, would eliminate 600 high-paying coal mining jobs.[10] Despite fears to the contrary, there has been little noticeable economic effect upon the City of Centralia as a result. Data indicates that Centralia is experiencing growth both in its light industrial areas as well as its core business district, historic downtown Centralia.[11] Additional development of regional distribution and transportation facilities, along with in-migration from retirees from more populated counties to the north, have helped diversify the economy, though unemployment remains stubbornly high and per-capita income well below the state average.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.56 square miles (19.58 km2), of which, 7.42 square miles (19.22 km2) is land and 0.14 square miles (0.36 km2) is water.[12]

Climate

This region experiences warm (but not hot) and dry summers, with no average monthly temperatures above 71.6 °F. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Centralia has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, abbreviated "Csb" on climate maps.[13] Temperatures are usually quite mild, although Centralia is generally warmer in the summer and colder in the winter than locations further north along the Puget Sound.

| Climate data for Centralia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

75 (24) |

85 (29) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

107 (42) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

75 (24) |

73 (23) |

107 (42) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 45.6 (7.6) |

50.1 (10.1) |

55.1 (12.8) |

61.5 (16.4) |

67.9 (19.9) |

72.8 (22.7) |

78.7 (25.9) |

78.5 (25.8) |

72.8 (22.7) |

62.3 (16.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

46.4 (8.0) |

62.0 (16.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 33.5 (0.8) |

34.6 (1.4) |

36.3 (2.4) |

39.1 (3.9) |

43.7 (6.5) |

48.4 (9.1) |

51.5 (10.8) |

51.3 (10.7) |

47.8 (8.8) |

43.0 (6.1) |

38.2 (3.4) |

34.8 (1.6) |

41.9 (5.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

0 (−18) |

14 (−10) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

33 (1) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

5 (−15) |

0 (−18) |

−4 (−20) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.65 (169) |

5.05 (128) |

4.75 (121) |

3.06 (78) |

2.30 (58) |

1.84 (47) |

0.70 (18) |

1.09 (28) |

2.00 (51) |

4.07 (103) |

7.03 (179) |

7.33 (186) |

45.89 (1,166) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.4 (8.6) |

1.4 (3.6) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

6.6 (16.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 20 | 17 | 18 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 14 | 20 | 21 | 164 |

| Source: WRCC[14] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 2,026 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,600 | −21.0% | |

| 1910 | 7,311 | 356.9% | |

| 1920 | 7,549 | 3.3% | |

| 1930 | 8,058 | 6.7% | |

| 1940 | 7,414 | −8.0% | |

| 1950 | 8,657 | 16.8% | |

| 1960 | 8,586 | −0.8% | |

| 1970 | 10,054 | 17.1% | |

| 1980 | 11,555 | 14.9% | |

| 1990 | 12,101 | 4.7% | |

| 2000 | 14,742 | 21.8% | |

| 2010 | 16,336 | 10.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 17,745 | [3] | 8.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] 2018 Estimate[16] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 16,336 people, 6,640 households, and 3,867 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,201.6 inhabitants per square mile (850.0/km2). There were 7,265 housing units at an average density of 979.1 per square mile (378.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.1% White, 0.6% African American, 1.4% Native American, 1.0% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 7.4% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 16.1% of the population.

There were 6,640 households, of which 31.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.7% were married couples living together, 14.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 41.8% were non-families. 33.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 3.06.

The median age in the city was 34.8 years. 24.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.7% were from 25 to 44; 22.3% were from 45 to 64; and 16.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.3% male and 51.7% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 14,742 people, 5,943 households, and 3,565 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,990.6 people per square mile (768.1/km2). There were 6,510 housing units at an average density of 879.0 per square mile (339.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.76% White, 0.44% African American, 1.25% Native American, 0.94% Asian, 0.30% Pacific Islander, 4.94% from other races, and 2.38% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 10.22% of the population.

There were 5,943 households, out of which 29.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.7% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.0% were non-families. 32.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.2% under the age of 18, 10.5% from 18 to 24, 25.7% from 25 to 44, 19.4% from 45 to 64, and 19.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,078, and the median income for a family was $35,684. Males had a median income of $31,595 versus $22,076 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,305. About 13.6% of families and 18.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.4% of those under age 18 and 10.8% of those age 65 or over.

Government and politics

Centralia is a noncharter code city with a council–manager form of government. The City Council consists of seven members with positions one through three being at-large positions.

Although slightly less so than Lewis County as a whole, Centralia is conservative and leans Republican.

Media

Centralia's leading newspaper is The Chronicle, ranked seventeenth in the state based on weekday circulation,[17] and serves most of Lewis County. There are also several community-based newspapers that are published bi-weekly, such as The Lewis County News and The East County Journal.

Radio

AM radio

FM radio

Education

Centralia College

Centralia College is the oldest continuously operating junior college in the state of Washington, and was founded on September 14, 1925.[18] Its first classes were held in the top floor of the Centralia High School building, and classes were taught by part-time teachers who also taught high school students.

The college found its beginning in large part due to the efforts of C. L. Littel, Centralia Public Schools Superintendent and Dean Frederick E. Bolton of the University of Washington School of Education. During the early years Centralia College prepared students who would later go on to enroll at the University of Washington, and a special partnership between the colleges remained in place until 1947. The following year Centralia College earned its accreditation from the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. Two years later the college's first major campus building, Kemp Hall, was constructed in the heart of Centralia.

The effort to expand and develop a separate campus was largely influenced by the end of World War II and the newly enacted GI Bill. This created an oversupply of new students ready to train for their careers, with limited space to do so. Just prior to this, enrollment had been shrinking, as many young Centralians and other residents of Lewis County had left to join the war effort. Prior to the war, the college's future had been in jeopardy during the Great Depression and resulting local bank closures. From approximately 1925 through the 1940s the college was primarily funded through private loans and donations from local businesses and community members, but steady funds were not always readily available. Credit for Centralia College surviving during these difficult times is in part given to Margaret Corbet, administrator, faculty member, and namesake of Corbet Hall, due to her efforts to keep the college financially afloat.[19][20]

Today, Centralia College is greatly expanded, both in physical plant with a campus covering several blocks and in curriculum offerings, including a full range of distribution classes for two-year AA degrees, a select few four-year degrees and a variety of technical skill sets taught at the college.

Culture

Seattle-based rock band Harvey Danger used Centralia as a metaphor in its song "Moral Centralia," found on the 2005 album Little by Little.

Local landmarks

Borst Home Built in 1864 at the site of the toll ferry crossing at the confluence of the Chehalis and Skookumchuck rivers, the Borst Home fulfilled a promise by Joseph Borst to his young wife Mary to build her the finest home along the Washington extension of the Oregon Trail. The original home is open to tour as part of the large Borst Park complex along I-5 exit 82.

Carnegie Library[21] is located in Washington Park and was originally built in 1913 followed by a remodel in 1977–78. The building houses a large chandelier taken from the old Centralia High School. The library is now part of the Timberland Regional Library system.

Centralia Square Built in 1920 by Joseph Wohleb, Washington's first professional architect, this long-time Elks Lodge was restored in 2015 to its original glory, including a 9-room boutique hotel with ballroom, two restaurants and the town's original antique mall. The building also features a mural depicting the laborer's side of the Centralia Massacre as a counterpoint to the statue commemorating the American Legionnaires slain in that incident, which stands in the Carnegie Library park across the street.

Centralia Union Depot was built in 1912 and features red brick architecture, vintage oak benches, and internal and external woodworking throughout. In 1996, restoration projects were started. They finished in 2002. The depot is currently served by Amtrak as the midpoint between stations in Kelso and Olympia. The depot is also served by connections to the Twin Transit Transportation system and is located within walking distance to Carnegie Library, Historic Fox Theater, McMenamin's Olympic Club Hotel & Theater, and Santa Lucia Coffee Company, as well as various eateries, shops and antique vendors.

Fox Theater[22] originally opened on September 5, 1930. It was built with approximately 1,200 seats over three seating levels. The first film seen by the public was Buster Keaton in Doughboys. In 1982 the theater underwent renovations and separated the main stage into three smaller screening areas. The theater closed in 1998 and was purchased by Opera Pacifica in 2004 and underwent initial stages of restoration. In 2007 the City of Centralia bought the theater and it is currently being further restored by the Historic Fox Theatre Restorations. Limited film performances began again in 2009.

McMenamin's Olympic Club Hotel & Theater[23][24] opened in 1908 followed by an extensive remodel in 1913. Since then much of the building has remained unchanged. The hotel hosts 27 European-style guestrooms. Each room is named after a person of interest, including Roy Gardner, a train robber caught behind the hotel in 1921. The club was originally only frequented by gentlemen but has been opened to families for many years. The theater shows second run films, musical and comedy performances, and some televised sports events. The theater has replaced theater seating with various chairs and couches throughout. The pub serves Terminator Stout, Hammerhead, Ruby and other beverages and food items. Adjoining the pub and dining area is a 6-table poolroom and snooker table that was recently rated in the top 5 for "Best Pool Hall in Western Washington." Every April or May the Olympic Club host its annual Brewfest, where local, import and guest brews are highlighted.

Public art

Murals are found throughout historic downtown Centralia. Examples include murals depicting the founder of Centralia (Centerville) named George Washington, Buffalo Bill and his Wild West Show and an abstract mural depicting the 1919 Armistice Day Centralia Massacre, also known as the Wobbly War.

Notable people

- Charlie Albright, pianist

- Calvin Armstrong, American football player

- Ann Boleyn, singer

- Bob Coluccio, baseball player

- Merce Cunningham, modern dancer

- Noah Gundersen, singer

- Soren Johnson, video game designer

- James Kelsey, sculptor

- Craig McCaw, entrepreneur

- Angela Meade, operatic soprano

- C.D. Moore, U.S. Air Force general

- Patricia Anne Morton, first woman to serve as a Diplomatic Security special agent[25]

- Lyle Overbay, baseball player

- Tavita Pritchard, American football coach

- Jimmy Ritchey, country music songwriter and record producer

- Detlef Schrempf, NBA player

Transportation

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Centralia station, stopping at the town's renovated 1912 railroad depot. Amtrak train 11, the southbound Coast Starlight, is scheduled to depart Centralia at 11:45am with service to Kelso-Longview, Portland, Sacramento, Emeryville, California (with bus connection to San Francisco), and Los Angeles. Amtrak train 14, the northbound Coast Starlight, is scheduled to depart Centralia at 5:57pm daily with service to Olympia-Lacey, Tacoma and Seattle. Amtrak Cascades trains, operating as far north as Vancouver, British Columbia and as far south as Eugene, Oregon, serve Centralia several times daily in both directions. BNSF trains in Centralia's downtown rail yard and on the mainline serve local and regional shippers, but can affect the timeliness of Amtrak service and are a noisy reminder of the days of the town's heyday as the crossroads of four major railroads (Union Pacific, Milwaukee Road, Great Northern and Northern Pacific).

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Centralia". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Johnson, Kraen (January 18, 2007). "Centralia, Washington (1875–)". BlackPast.

- Oldham, Kit (February 23, 2003). "George and Mary Jane Washington found the town of Centerville (now Centralia) on January 8, 1875". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- Wobbly War: The Centralia Story, John McClellan, ISBN 0917048628

- Ott, Jennifer (February 12, 2008). "Centralia — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/msh/impact

- Daily Olympian article

- Boone, Rolf. Unemployment claims dropped more than 300 from peak, report says. The Olympian. May 17, 2007.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Centralia, Washington Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)".

- "CENTRALIA, WASHINGTON (451276)". Western Regional Climate Centre. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "Centralia College holds its first day of classes on September 14, 1925". HistoryLink.

- www.centralia.edu, Centralia College for. "About Centralia College". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 12, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "www.trl.org". Archived from the original on 2013-10-06. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- "Home".

- "Olympic Club - Olympic Club Pub - McMenamins".

- TEGNA. "Best of Western Washington". Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- "Patricia Anne Morton May 30 1935 October 16 2019 (age 84), death notice, USA". United States Obituary Notice. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2020.