Rudolf Caracciola

Otto Wilhelm Rudolf Caracciola[1] (30 January 1901 – 28 September 1959) was a racing driver from Remagen, Germany. He won the European Drivers' Championship, the pre-1950 equivalent of the modern Formula One World Championship, an unsurpassed three times. He also won the European Hillclimbing Championship three times – twice in sports cars, and once in Grand Prix cars. Caracciola raced for Mercedes-Benz during their original dominating Silver Arrows period, named after the silver colour of the cars, and set speed records for the firm. He was affectionately dubbed Caratsch by the German public,[2] and was known by the title of Regenmeister, or "Rainmaster", for his prowess in wet conditions.

| Rudolf Caracciola | |

|---|---|

Caracciola in 1928 | |

| Nationality | German (naturalized Swiss in November 1946) |

| Born | Otto Wilhelm Rudolf Caracciola 30 January 1901 Remagen, German Empire |

| Died | 28 September 1959 (aged 58) Kassel, West Germany |

| Retired | 1952 |

| European Championship | |

| Years active | 1931–1932, 1935–1939 |

| Teams | Mercedes-Benz (1931, 1935–1939) Alfa Romeo (1932) |

| Starts | 26 |

| Wins | 11 |

| Championship titles | |

| 1935, 1937, 1938 | Drivers' Championship |

| European Hillclimbing Championship | |

| Years active | 1930–1932 |

| Teams | Mercedes-Benz (1930–1931) Alfa Romeo (1932) |

| Championship titles | |

| 1930, 1931 1932 | Sports cars Grand Prix cars |

Caracciola began racing while he was working as apprentice at the Fafnir automobile factory in Aachen during the early 1920s, first on motorcycles and then in cars. Racing for Mercedes-Benz, he won his first two Hillclimbing Championships in 1930 and 1931, and moved to Alfa Romeo for 1932, where he won the Hillclimbing Championship for the third time. In 1933, he established the privateer team Scuderia C.C. with his fellow driver Louis Chiron, but a crash in practice for the Monaco Grand Prix left him with multiple fractures of his right thigh, which ruled him out of racing for more than a year. He returned to the newly reformed Mercedes-Benz racing team in 1934, with whom he won three European Championships, in 1935, 1937 and 1938. Like most German racing drivers in the 1930s, Caracciola was a member of the Nazi paramilitary group National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK), but never a member of the Nazi Party. He returned to racing after the Second World War, but crashed in qualifying for the 1946 Indianapolis 500. A second comeback in 1952 was halted by another crash, in a sports car race in Switzerland.

After he retired, Caracciola worked as a Mercedes-Benz salesman targeting North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) troops stationed in Europe. He died in the German city of Kassel, after suffering liver failure. He was buried in Switzerland, where he had lived since the early 1930s. He is remembered as one of the greatest pre-1939 Grand Prix drivers, a perfectionist who excelled in all conditions. His record of six German Grand Prix wins remains unbeaten.

Early life and career

Rudolf Caracciola was born in Remagen, Germany, on 30 January 1901. He was the fourth child of Maximilian and Mathilde, who ran the Hotel Fürstenberg. His ancestors had migrated during the Thirty Years' War from Naples to the German Rhineland, where Prince Bartolomeo Caracciolo (nephew of Spanish-allegiance Field Marshal Tommaso Caracciolo) had commanded the Ehrenbreitstein Fortress near Koblenz.[1] Caracciola was interested in cars from a young age, and from his fourteenth birthday wanted to become a racing driver.[3] He drove an early Mercedes during the First World War,[4] and gained his driver's license before the legal age of 18. After Caracciola's graduation from school soon after the war, his father wanted him to attend university, but when he died Caracciola instead became an apprentice in the Fafnir automobile factory in Aachen.[3][5]

Motorsport in Germany at the time, as in the rest of Europe, was an exclusive sport, mainly limited to the upper classes. As the sport became more professional in the early 1920s, specialist drivers, like Caracciola, began to dominate.[6] Caracciola enjoyed his first success in motorsport while working for Fafnir, taking his NSU motorcycle to several victories in endurance events.[5] When Fafnir decided to take part in the first race at the Automobil-Verkehrs- und Übungs-Straße (AVUS) track in 1922, Caracciola drove one of the works cars to fourth overall, the first in his class and the quickest Fafnir.[4][5] He followed this with victory in a race at the Opelbahn in Rüsselsheim.[4] He did not stay long in Aachen, however; in 1923, after punching a soldier from the occupying Belgian Army in a nightclub, he fled the city.[5][7] He moved to Dresden, where he continued to work as a Fafnir representative. In April of that year, Caracciola won the 1923 ADAC race at the Berlin Stadium in a borrowed Ego 4 hp.[4][8] In his autobiography, Caracciola said he only ever sold one car for Fafnir, but due to inflation by "the time the car was delivered the money was just enough to pay for the horn and two headlights".[9]

Later in 1923, he was hired by the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft as a car salesman at their Dresden outlet. Caracciola continued racing, driving a Mercedes 6/25/40 hp to victory in four of the eight races he entered in 1923.[4][5] His success continued in 1924 with the new supercharged Mercedes 1.5-litre; he won 15 races during the season, including the Klausenpass hillclimb in Switzerland.[5] He attended the Italian Grand Prix at Monza as a reserve driver for Mercedes, but did not take part in the race.[10] He drove his 1.5-litre to five victories in 1925,[5] and won the hillclimbs at Kniebis and Freiburg in a Mercedes 24/100/140 hp.[4] With his racing career becoming increasingly successful, he abandoned his plans to study mechanical engineering.[5]

1926–1930: Breakthrough

Caracciola's breakthrough year was in 1926. The inaugural German Grand Prix was held at the AVUS track on 11 July, but the date clashed with a more prestigious race in Spain. The newly merged company Mercedes-Benz, conscious of export considerations, chose the latter race to run their main team.[11] Hearing this, Caracciola took a short leave from his job and went to the Mercedes office in Stuttgart to ask for a car.[11] Mercedes agreed to lend Caracciola and Adolf Rosenberger two 1923 2-litre M218s, provided they enter not as works drivers but independents.[12][13] Rosenberger started well in front of the 230,000 spectators, but Caracciola stalled his engine.[5] His riding mechanic, Eugen Salzer, jumped out and pushed the car to get it started, but by the time they began moving they had lost more than a minute to the leaders.[14] It started to rain, and Caracciola passed many cars that had retired in the poor conditions. Rosenberger lost control at the North Curve on the eighth lap when trying to pass a slower car, and crashed into the timekeepers' box, killing all three occupants; Caracciola kept driving.[13] In the fog and rain, he had no idea which position he was in, but resolved to keep driving so he could at least finish the race. When he finished the 20th and final lap, he was surprised to find that he had won the race.[15] The German press dubbed him Regenmeister, or "Rainmaster", for his prowess in the wet conditions.[13]

Caracciola used the prize money—17,000 Reichsmarks—to set up a Mercedes-Benz dealership on the prestigious Kurfürstendamm in Berlin.[5][16] He also married his girlfriend, Charlotte, whom he had met in 1923 while working at the Mercedes-Benz outlet in Dresden.[4] He continued racing in domestic competitions, returning again to Freiburg to compete in the Flying Kilometre race where he set a new sports car record in the new Mercedes-Benz 2-litre Model K, and finished first.[17] Caracciola entered the Klausenpass hillclimb and set a new touring car record; he also won the touring car class at the Semmering hillclimb before driving a newly supercharged 1914 Mercedes Grand Prix car over the same route to set the fastest time of the day for any class.[18] The recently completed Nürburgring was the host of the 1927 Eifelrennen, a race which had been held on public roads in the Eifel mountains since 1922. Caracciola won the first race on the track, and returned to the Nürburgring a month later for the 1927 German Grand Prix, but his car broke down and the race was won by Otto Merz.[19] However, he won 11 competitions in 1927, almost all of them in the Ferdinand Porsche-developed Mercedes-Benz Model S.[4]

Caracciola regained his German Grand Prix title at the Nürburgring at the 1928 German Grand Prix, driving the new 7.1-litre Mercedes-Benz SS.[20] He shared the driving with Christian Werner, who took over Caracciola's car when the latter collapsed with heat exhaustion at a pit stop.[21] The German Grand Prix, like many other races at the time, ignored the official Grand Prix racing rules set by the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus (International Association of Recognized Auto Clubs, or AIACR), which limited weight and fuel consumption, and instead ran races under a Formula Libre, or free formula. As a result, Mercedes-Benz focused less on producing Grand Prix cars and more on sports cars, and Caracciola drove the latest incarnation of this line, the SSK, at the Semmering hillclimb, and further reduced his own record on the course by half a second.[22]

The inaugural Monaco Grand Prix was held on 14 April 1929. Caracciola, driving a 7.1-litre Mercedes-Benz SSK, started from the back row of the grid (which was allocated randomly), and battled Bugatti driver William Grover-Williams for the lead early on.[23] However, his pit stop, which took four and a half minutes to refill his car with petrol, left him unable to recover the time, and he eventually finished third.[24] He won the RAC Tourist Trophy in slippery conditions, and confirmed his reputation as a specialist in wet track racing. He partnered Werner in the Mille Miglia and Le Mans endurance races in 1930; they finished sixth in the former but were forced to retire after leading for most of the race in the latter after their car's generator burnt out.[25] Caracciola took victory in the 1930 Irish Grand Prix at Phoenix Park,[26] and won four hillclimbs to take the title of European Hillclimb Champion for the first time.[4] However, he was forced to close his dealership in Berlin after the firm went bankrupt.[27]

1931–1932: Move to Alfa Romeo

Mercedes-Benz officially withdrew from motor racing in 1931—citing the global economic downturn as a reason for their decision—although they continued to support Caracciola and a few other drivers covertly, retaining manager Alfred Neubauer to run the 'independent' operation.[28] In part because of the financial situation, Caracciola was the only Mercedes driver to appear at the 1931 Monaco Grand Prix, driving an SSKL (a shorter version of the SSK).[29] Caracciola and Maserati driver Luigi Fagioli challenged the Bugattis of Louis Chiron and Achille Varzi for the lead early in the race, but when the SSKL's clutch failed Caracciola withdrew from the race.[30] A crowd of 100,000 turned out for the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring. Rain began to fall before the race, and continued as Caracciola chased Fagioli for the lead in the early laps. The spray from Fagioli's Maserati severely impaired Caracciola's vision, but he was able to pass to take the lead at the Schwalbenschwanz corner. The track began to dry on lap six, and Chiron's Bugatti, which was by then running second, began to catch the heavier Mercedes. Caracciola's pit stop, completed in record time, kept him ahead of Chiron, and despite the Bugatti lapping 15 seconds faster than the Mercedes late in the race, Caracciola won by more than one minute.[31]

Caracciola was lucky to escape from a crash in the Masaryk Grand Prix. He and Chiron were chasing Fagioli when Fagioli crashed into a wooden footbridge, bringing it crashing down onto the road. Caracciola and Chiron drove into a ditch at the side of the road to avoid the debris; while Chiron drove out of the ditch and was able to continue, Caracciola drove into a tree and retired.[32] Despite this accident, Caracciola again performed strongly in the Hillclimbing Championship; he won eight climbs in his SSKL to take the title.[33] Perhaps his most significant achievement of 1931 was his win in the Mille Miglia. The local fleet of Alfa Romeos battled for the lead early in the race, but when they fell back Caracciola was able to take control. His win, in record time, made him and his co-driver Wilhelm Sebastian (who allowed Caracciola to drive the entire race) the first foreigners to win the Italian race. The only other foreigners to win the race on the full course were Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson in 1955.[34]

Mercedes-Benz withdrew entirely from motor racing at the start of 1932 in the face of the economic crisis, so Caracciola moved to Alfa Romeo with a promise to return to Mercedes if they resumed racing.[35] His contract stipulated he would begin racing for the Italian team as a semi-independent. Caracciola later wrote that the Alfa Romeo manager was defensive when he questioned him about this clause; Caracciola believed it was because the firm's Italian drivers did not believe he could change from the huge Mercedes cars to the much smaller Alfa Romeos.[36] His first race for his new team was at the Mille Miglia; he led early in the race, but retired when a valve connection broke. Caracciola later wrote, "I can still see the expression on [Alfa Romeo driver Giuseppe] Campari's face when I arrived back at the factory. He smiled to himself as if to say, Well, didn't I tell you that one wasn't going to make it?"[37]

The next race was the Monaco Grand Prix, where Caracciola was again entered as a semi-independent. He ran fourth early in the race, but moved to second as Alfa Romeo driver Baconin Borzacchini pitted for a wheel change and the axle on Achille Varzi's Bugatti broke. Tazio Nuvolari, in the other Alfa Romeo, found his lead reduced rapidly as Caracciola closed in; with ten laps remaining in the race Caracciola was so close he could see Nuvolari changing gears. He finished the race just behind Nuvolari. The crowd jeered Caracciola: they believed he had deliberately lost for the team, denying them a fight for the win. However, on the strength of his performance, Caracciola was offered a full spot on the Alfa Romeo team, which he accepted.[38]

Alfa Romeo dominated the rest of the Grand Prix season. Nuvolari and Campari drove the newly introduced Alfa Romeo P3 at the Italian Grand Prix, while Borzacchini and Caracciola drove much heavier 8Cs. Caracciola was forced to retired when his car broke down, but he took over Borzacchini's car when the Italian was hit by a stone, and came third, behind Nuvolari and Fagioli.[39] In the French Grand Prix, Caracciola, now driving a P3, battled Nuvolari for the lead early on. Alfa Romeo's dominance was so great and their cars so far ahead the team could choose the top three finishing positions, thus Nuvolari won from Borzacchini and Caracciola, with the two Italians ahead of the German. The order was different at the 1932 German Grand Prix, where Caracciola won from Nuvolari and Borzacchini.[40]

Caracciola performed strongly in other races; he won the Polish and Monza Grands Prix and the Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring, and took five more hillclimbs to win that Championship for the third and final time.[41] He was, however, beaten by the Mercedes-Benz of Manfred von Brauchitsch at the Avusrennen (the yearly race at the AVUS track). Von Brauchitsch drove a privately entered SSK with streamlined bodywork, and beat Caracciola's Alfa Romeo, which finished in second place. Caracciola was seen by the German crowd as having defected to the Italian team and was booed, while von Brauchitsch's all German victory drew mass support.[42]

1933–1934: Injury and return for Mercedes

Alfa Romeo withdrew its factory team from motor racing at the start of the 1933 season, leaving Caracciola without a contract. He was close friends with the Monegasque driver Louis Chiron, who had been fired from Bugatti, and while on vacation in Arosa in Switzerland the two decided to form their own team, Scuderia C.C. (Caracciola-Chiron).[43] They bought three Alfa Romeo 8Cs (known as Monzas), and Daimler-Benz provided a truck to transport them.[44][45] Chiron's car was painted blue with a white stripe, and Caracciola's white with a blue stripe.[43] The new team's first race was at the Monaco Grand Prix. On the second day of practice for the race, while Caracciola was showing Chiron around the circuit (it was Chiron's first time in an Alfa Romeo), the German lost control heading into the Tabac corner. Three of the four brakes failed, which destabilised the car. Faced with diving into the sea or smashing into the wall, Caracciola instinctively chose the latter.[46] Caracciola later recounted what happened after the impact:

Only the body of the car was smashed, especially around my seat. Carefully I drew my leg out of the steel trap. Bracing myself against the frame of the body, I slowly extricated myself from the seat ... I tried to hurry out of the car. I wanted to show that nothing had happened to me, that I was absolutely unhurt. I stepped to the ground. At that instant the pain flashed through my leg. It was a ferocious pain, as if my leg were being slashed by hot, glowing knives. I collapsed, Chiron catching me in his arms.[47]

Caracciola was carried on a chair to the local tobacco shop, and from there he went to the hospital.[48] He had sustained multiple fractures of his right thigh, and his doctors doubted he would race again.[43] He transferred to a private clinic in Bologna, where his injured leg remained in a plaster cast for six months.[48][49] Caracciola defied the predictions of his doctors and healed faster than expected, and in the winter Charlotte took her husband back to Arosa, where the altitude and fresh air would aid his recovery.[43]

The rise to power of the Nazi Party on 30 January 1933 gave German motor companies, notably Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, an opportunity to return to motor racing. Having secured promises of funding shortly after the Nazis' rise to power, both companies spent the better part of 1933 developing their racing projects.[50] Alfred Neubauer, the Mercedes racing manager, travelled to the Caracciolas' chalet in Lugano in November with a plan to sign him for the 1934 Grand Prix season if he was fit. Neubauer challenged Caracciola to walk, and although the driver laughed and smiled while he did so Neubauer was not fooled: Caracciola was not yet fit. Nevertheless, he offered him a contract, provided he prove his fitness in testing at the AVUS track early in the next year. Caracciola agreed and went to Stuttgart to sign the contract. The trip wore him out so much he spent much of his time lying on his hotel bed recuperating.[51]

Upon his return to Lugano, another tragedy befell him. In February, Charlotte died when the party she was skiing with in the Swiss Alps was hit by an avalanche. Caracciola withdrew almost entirely from public life while he mourned, almost deciding to retire completely from motor racing.[51][52] A visit from Chiron encouraged him to return to racing, and despite his initial reservations he was persuaded to drive the lap of honour before the 1934 Monaco Grand Prix.[51] Although his leg still ached while he drove, the experience convinced him to return to racing.[53]

Caracciola tested the new Mercedes-Benz W25 at the AVUS track in April, and despite his injuries—his right leg had healed five 5 centimetres (2.0 in) shorter than his left, leaving him with a noticeable limp—he was cleared to race.[54] However, Neubauer withdrew the Mercedes team from their first race, also at the AVUS track, as their practice times compared too unfavourably to Auto Union's.[55] Caracciola was judged not fit to race for the Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring,[56] but made the start for the German Grand Prix at the same track six weeks later. He took the lead from Auto Union driver Hans Stuck on the outside of the Karussel on the 13th lap, but retired a lap later when his engine failed.[57] He had better luck at the 1934 Italian Grand Prix in September. In very hot weather, Caracciola started from fourth and moved to second, where he trailed Stuck. After 59 laps, the pain in his leg overwhelmed him, and he pitted, letting teammate Fagioli take over his car. Fagioli won from Stuck's car which by then had been taken over by Nuvolari.[58] His best results in the rest of the season were a second place in the Spanish Grand Prix—he led before Fagioli passed him, much to the anger of Neubauer, who had ordered the Italian to hold position—and first at the Klausenpass hillclimb.[59][60]

1935–1936: First Championship and rivalry with Rosemeyer

Caracciola took the first of his three European Drivers' Championships in 1935. Seven Grands Prix—the Monaco, French, Belgian, German, Swiss, Italian and Spanish—would be included for Championship consideration.[60] He opened the Championship season with a pole in Monaco but he retired just after the half of the race, then he won in France and took the lead of the standings with another win in Belgium, ahead of Fagioli and von Brauchitsch, who shared the other Mercedes-Benz W25.[61] Nuvolari won a surprise victory at the Nürburgring in his Alfa Romeo P3, ahead of Stuck and Caracciola. The Swiss Grand Prix was held at the Bremgarten Circuit in Bern, and Caracciola won from Fagioli and the new Auto Union star Bernd Rosemeyer. Caracciola won the Spanish Grand Prix from Fagioli and von Brauchitsch; although his transmission failed at the Italian Grand Prix and he was forced to retire, his three wins allowed him to take the Championship.[62]

In the other races of the 1935 season, Caracciola won the Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring and finished second at the Penya Rhin Grand Prix in Barcelona.[63] He also won the Tripoli Grand Prix, organised by the Libyan Governor-General Italo Balbo. The Grand Prix was held in the desert, around a salt lake, and because of the intense heat Neubauer was concerned that the tyres on the Mercedes-Benz cars would not last. Caracciola started poorly, but moved to third, after four pit stops to change tyres, by lap 30 of 40. He inherited the lead from Nuvolari and Varzi when the two Italians pitted, and held it to the finish, despite a late charge from Varzi.[48] Caracciola later wrote that this was the race where he began to feel he had recovered from his crash in Monaco two years before, and he was now back among the contenders.[64]

Remaining in such a position would require Mercedes-Benz to produce a competitive car for the 1936 season. Although the chassis of the W25 was shortened, and the engine was significantly upgraded to 4.74 litres, the car proved inferior to the Type C developed by Auto Union.[65] Mercedes had not improved the chassis to match the engine, and the W25 proved uncompetitive and unreliable.[63][66] Despite this, Caracciola opened the season with a win in the rain at the Monaco Grand Prix, after starting from third position. He led the Hungarian Grand Prix early but retired with mechanical problems.[67] At the German Grand Prix, he retired with a failed fuel pump, before taking over his teammate Hermann Lang's car; he later retired that car with supercharger problems.[68] Caracciola led the Swiss Grand Prix for several laps, Rosemeyer trailing him closely, but the Clerk of the Course ordered Caracciola to cede the lead to Rosemeyer on the ninth lap after he was found to be blocking the Auto Union.[65] The two had a heated argument after the race despite Caracciola's later retirement with a rear axle problem.[69] Mercedes were so uncompetitive in 1936—Caracciola won only twice, in Monaco and Tunis—that Neubauer withdrew the team mid-season, leaving Rosemeyer to take the Championship for Auto Union.[70]

1937: Second Championship

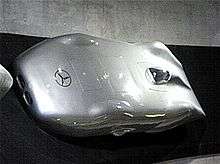

Mercedes-Benz returned to Grand Prix racing at the start of the 1937 season with a new car. The W125 was a vast improvement on its predecessor, its supercharged eight cylinder 5.6-litre engine delivered significantly more power than the W25: 650 brake horsepower compared to 500.[71][72] The first major race of 1937 was the Avusrennen where 300,000 people turned out to see the cars race on the newly re-constructed track. In order to keep speeds consistently high, the north curve was turned into a steeply banked turn, apparently at the suggestion of Adolf Hitler.[73] Driving a streamlined Mercedes-Benz, Caracciola won his heat against Rosemeyer, averaging around 250 kilometres per hour (160 mph), although a transmission failure forced him to retire in the final.[74][75] Following the AVUS race, Caracciola, along with Rosemeyer, Nuvolari and Mercedes' new driver, Richard Seaman, went to race in the revived Vanderbilt Cup in America, and in doing so missed the Belgian Grand Prix, which took place six days later.[76] Caracciola led until lap 22, when he retired with a broken supercharger.[75]

Caracciola started from the second row of the grid at the German Grand Prix, but was into the lead soon after the start. There he remained to the finish, in front of von Brauchitsch and Rosemeyer.[77] He took pole position at the Monaco Grand Prix three weeks later, and was soon engaged in a hard fight with von Brauchitsch.[78] The Mercedes-Benz drivers took the lead from each other several times, but von Brauchitsch won after a screw fell into Caracciola's induction system during a pit stop, costing him three and a half minutes.[79] Caracciola won his second race of the season at the Swiss Grand Prix. Despite heavy rain which made the Bremgarten Circuit slippery and hazardous, Caracciola set a new lap record, at an average speed of 169 kilometres per hour (105 mph), and cemented his reputation as the Regenmeister.[80]

For the first time, the Italian Grand Prix was held at the Livorno Circuit rather than the traditional venue of Monza.[80] Caracciola took pole position, and despite two false starts caused by spectators pouring onto the track, held his lead for the majority of the race and won from his teammate Lang by just 0.4 seconds.[81] In doing so Caracciola clinched the European Championship for the second time.[80] He backed up the win with another at the Masaryk Grand Prix two weeks later. He trailed Rosemeyer for much of the race until the Auto Union skidded against a kerb and allowed the Mercedes into the lead.[82]

Caracciola married for the second time in 1937, to Alice Hoffman-Trobeck, who worked as a timekeeper for Mercedes-Benz.[83] He had met her in 1932, when she was having an affair with Chiron. She was, at that time, married to Alfred Hoffman-Trobeck, a Swiss businessman and heir to a pharmaceutical empire.[84] She had taken care of Caracciola after Charlotte died, and shortly after began an affair with him, unbeknownst to Chiron.[85] They were married in June in Lugano, just before the trip to America.[86]

1938: Speed records and third Championship

On 28 January 1938, Caracciola and the Mercedes-Benz record team appeared on the Reichs-Autobahn A5 between Frankfurt and Darmstadt, in an attempt to break numerous speed records set by the Auto Union team.[87] The system of speed records at the time used classes based on engine capacity, allowing modified Grand Prix cars, in this case a W125, to be used to break records. Caracciola had broken previous records—he reached 311.985 kilometres per hour (193.858 mph) in 1935—but these had been superseded by Auto Union drivers, first Stuck and then Rosemeyer.[88] Driving a Mercedes-Benz W125 Rekordwagen, essentially a W125 with streamlined bodywork and a larger engine, Caracciola set a new average speed of 432.7 kilometres per hour (268.9 mph) for the flying kilometre and 432.4 kilometres per hour (268.7 mph) for the flying mile, speeds which remain to this day as some of the fastest ever achieved on public roads.[87][89] The day ended in tragedy however; Rosemeyer set off in his Auto Union in an attempt to break Caracciola's new records, but his car was struck by a violent gust of wind while he was travelling at around 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph), hurling the car off the road, where it rolled twice, killing its driver.[90] Rosemeyer's death had a profound effect on Caracciola, as he later wrote:

What was the sense in men chasing each other to death for the sake of a few seconds? To serve progress? To serve mankind? What a ridiculous phrase in the face of the great reality of death. But then—why? Why? And for the first time, at that moment, I felt that every life is lived according to its own laws. And that the law for a fighter is: to burn oneself up to the last fibre, no matter what happens to the ashes.[91]

The Grand Prix formula was changed again in 1938, abandoning the previous system of weight restrictions and instead limiting piston displacement.[92] Mercedes-Benz' new car, the W154, proved its abilities at the French Grand Prix, where von Brauchitsch won ahead of Caracciola and Lang to make it a Mercedes 1–2–3.[93] Caracciola won two races in the 1938 season: the Swiss Grand Prix and the Coppa Acerbo; finished second in three: the French, German and Pau Grands Prix; and third in two: the Tripoli and Italian Grands Prix, to take the European Championship for the third and final time.[94] The highlight of Caracciola's season was his win in the pouring rain at the Swiss Grand Prix. His teammate Seaman led for the first 11 laps before Caracciola passed him; he remained in the lead for the rest of the race, despite losing the visor on his helmet, severely reducing visibility, especially given the spray thrown up by tyres of the many lapped cars.[95]

1939: Claims of favouritism towards Lang

The 1939 season took place under the looming shadow of the coming Second World War, and the schedule was only halted with the invasion of Poland in September.[96] The Championship season began with the Belgian Grand Prix in June. In heavy rain, Caracciola spun at La Source, got out and pushed his car off into the safety of the trees. Later in the race, Seaman left the track at the same corner, his car bursting into flames upon impact with the trees, where he was burnt alive in the cockpit. He died that night in hospital, after briefly regaining consciousness. The entire Mercedes team travelled to London for his burial.[97] In the rest of the season, Caracciola won the German Grand Prix for the sixth and final time, again in the rain, after starting third on the grid.[98][99] He finished second behind Lang at the Swiss and Tripoli Grands Prix. The latter race was seen as a major win for Mercedes-Benz. In an effort to halt German dominance at the event, the Italian organisers decided to limit engine sizes to 1.5 litres (the German teams at the time ran 3-litre engines), and announce the change at the last moment. The change was, however, leaked to Mercedes-Benz well in advance, and in just eight months the firm developed and built two W165s under the new restrictions; both of them beat the combined might of 28 Italian cars, much to the disappointment of the organisers.[100] Caracciola believed that the Mercedes-Benz team were favouring Lang during the 1939 season; in a letter sent to Mercedes' brand owner Daimler-Benz CEO Dr. Wilhelm Kissel, he wrote:

I see little chance of the situation changing at all. Starting with Herr Sailer [Max Sailer, then the head of the Mercedes racing division] through Neubauer, down to the mechanics, there is an obsession with Lang. Herr Neubauer admitted frankly to Herr von Brauchitsch that he was standing by the man who has good luck, and whom the sun shines on ... I really enjoy racing and want to go on driving for a long time. However, this presupposes that I fight with the same weapons as my stablemates. Yet this will be hardly possible in the future, as almost all the mechanics and engine specialists in the racing division are on Lang's side ...[101]

Despite Caracciola's protests, Lang was declared the 1939 European Champion by the NSKK (Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps, or National Socialist Motor Corps)—although this was never ratified by the AIACR, and Auto Union driver Hermann Paul Müller may have a valid claim to the title under the official scoring system—and motor racing was put on hold upon the outbreak of war.[102]

War, comeback and later years

Caracciola and his wife Alice returned to their home in Lugano. For the duration of the war he was unable to drive; the rationing of petrol meant motor racing was unfeasible. The pain in his leg grew worse, and they went back to the clinic in Bologna to consult a specialist. Surgery was recommended, but Caracciola decided against that option, deterred by the minimum three months it would take to recover from the operation.[103] He spent much of the last part of the war—from 1941 onwards—attempting to gain possession of the two W165s used at the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix, with a view to maintaining them for the duration of the hostilities.[104] When they finally arrived in Switzerland in early 1945, they were confiscated as German property by the Swiss authorities.[105]

He was invited to participate in the 1946 Indianapolis 500, and originally intended to drive one of the W165s, but was unable to have them released in time.[106] Nevertheless, he headed to America to watch the race. Joe Thorne, a local team owner, offered him one of his Thorne Engineering Specials to drive,[107] but during a practice session before the race Caracciola was hit on the head by an object, believed to be a bird, and crashed into the south wall.[106] His life was saved by a tank driver's helmet the organisers insisted he wear. He suffered a severe concussion and was in a coma for several days.[106][108] Tony Hulman, owner of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, invited Caracciola and his wife to stay at his lodge near Terre Haute to let him fullly recover.[109]

Caracciola returned to racing in 1952, when he was recalled to the Mercedes-Benz factory team to drive the new Mercedes-Benz W194 in sports car races.[110] The first major race with the car was the Mille Miglia, alongside Karl Kling and his old teammate Hermann Lang. Kling finished second in the race, Caracciola fourth. It later emerged that Caracciola had been given a car with an inferior engine to his teammates, perhaps because of a lack of time to prepare for the race.[111] Caracciola's career ended with his third major crash; during a support race for the 1952 Swiss Grand Prix, the brakes on his 300SL locked and he skidded into a tree, fracturing his left leg.[54][112]

After his retirement from racing, he continued to work for Daimler-Benz as a salesman, targeting NATO troops stationed in Europe. He organised shows and demonstrations which toured military bases, leading in part to an increase in Mercedes-Benz sales during that period.[113] In early 1959, he became sick and developed signs of jaundice, which worsened despite treatment. Later in the year he was diagnosed with advanced cirrhosis.[113] On 28 September 1959, in Kassel, Germany, he suffered liver failure and died, aged 58.[4][114] He was buried in his home town of Lugano.[115]

Nazi interactions

Caracciola first met Adolf Hitler, the leader of the Nazi Party, in 1931. Hitler had ordered a Mercedes-Benz 770, at that point Mercedes' most expensive car, but due to the amount of time spent upgrading the car in line with the Nazi leader's wishes, the delivery was late. To mollify Hitler's anger, Caracciola was dispatched by Mercedes to deliver the car to the Brown House in Munich. Caracciola drove Hitler and his niece Geli Raubal around Munich to demonstrate the car.[116] He later wrote (after the fall of the Nazi Party) that he was not particularly awed by Hitler: "I could not imagine that this man would have the requirements for taking over the government someday."[117]

Like most German racing drivers in Nazi Germany, Caracciola was a member of the NSKK,[118] a paramilitary organisation of the Nazi Party devoted to motor racing and motor cars; during the Second World War it handled transport and supply.[119] In reports on races by German media Caracciola was referred to as NSKK-Staffelführer Caracciola, the equivalent of a Squadron Leader. After races in Germany the drivers took part in presentations to the crowd coordinated by NSKK leader Adolf Hühnlein and attended by senior Nazis.[120] Although he wrote after the fall of the Nazi regime that he found such presentations dull and uninspiring, Caracciola occasionally used his position as a famous racing driver to publicly support the Nazi regime; for example, in 1938, while supporting the Nazi platform at the Reichstag elections, he said, "[t]he unique successes of these new racing cars in the past four years are a victorious symbol of our Führer's (Hitler's) achievement in rebuilding the nation."[121]

Despite this, when Caracciola socialised with the upper Nazi echelons he did so merely as an "accessory", not as an active member, and at no time was he a member of the Nazi Party.[122] According to his autobiography, he turned down a request from the NSKK in 1942 to entertain German troops, as he "could not find it in myself to cheer up young men so that they would believe in a victory I myself could not believe in".[123] Caracciola lived in Switzerland from the early 1930s,[124] and despite strict currency controls, his salary was paid in Swiss francs. During the war, he continued to receive a pension from Daimler-Benz, until the firm ceased his payments under pressure from the Nazi party in 1942.[125]

Legacy

Caracciola is remembered—along with Nuvolari and Rosemeyer—as one of the greatest pre-1939 Grand Prix drivers.[126] He has a reputation of a perfectionist, who very rarely had accidents or caused mechanical failures in his cars, who could deliver when needed regardless of the conditions.[48][127] His relationship with Mercedes racing manager Alfred Neubauer, one of mutual respect, is often cited as a contributing factor to his success.[127][128] After Caracciola's death, Neubauer described him as:

... the greatest driver of the twenties and thirties, perhaps even of all time. He combined, to an extraordinary extent, determination with concentration, physical strength with intelligence. Caracciola was second to none in his ability to triumph over shortcomings.[129]

His trophy collection was donated to the Indianapolis Hall of Fame Museum,[130] and he was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1998.[131] In 2001, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, a monument to Caracciola was erected in his birth town of Remagen,[132] and on the 50th anniversary of his death in 2009 Caracciola Square was dedicated off of the town's Rheinpromenade.[133] Karussel corner at the Nürburgring was renamed after him, officially becoming the Caracciola Karussel.[4] As of 2014, Caracciola's record of six German Grand Prix victories remains unbeaten.

During the inaugural official meeting of the 200 Mile Per Hour Club on 2 September 1953, Caracciola was inducted as one of the original three foreigners who met the club's requirements of achieving an average of over 200 mph over two runs for his past achievements prior to the club's foundation.[134]

Racing record

Complete 24 Hours of Le Mans results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Laps | Pos. | Class Pos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | Mercedes-Benz SS | 8.0 | 85 | DNF | DNF | ||

Source:[135] | |||||||

Complete European Championship results

(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) (Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | EDC | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | R. Caracciola | Mercedes-Benz SSKL | Mercedes-Benz 7.1 L6 | ITA | FRA Ret |

BEL | 27th | 22 | ||||

| 1932 | SA Alfa Romeo | Alfa Romeo Monza | Alfa Romeo 2.3 L8 | ITA 11 |

3rd | 9 | ||||||

| Alfa Romeo Tipo B/P3 | Alfa Romeo 2.6 L8 | FRA 3 |

GER 1 |

|||||||||

| 1935 | Daimler-Benz AG | Mercedes W25B | Mercedes 4.0 L8 | MON Ret |

FRA 1 |

BEL 1 |

GER 3 |

SUI 1 |

ITA Ret |

ESP 1 |

1st | 17 |

| 1936 | Daimler-Benz AG | Mercedes W25C | Mercedes 4.7 L8 | MON 1 |

GER Ret |

SUI Ret |

ITA | 6th | 22 | |||

| 1937 | Daimler-Benz AG | Mercedes W125 | Mercedes 5.7 L8 | BEL | GER 1 |

MON 2 |

SUI 1 |

ITA 1 |

1st | 13 | ||

| 1938 | Daimler-Benz AG | Mercedes W154 | Mercedes 3.0 V12 | FRA 2 |

GER 2 |

SUI 1 |

ITA 3 |

1st | 8 | |||

| 1939 | Daimler-Benz AG | Mercedes W154 | Mercedes 3.0 V12 | BEL Ret |

FRA Ret |

GER 1 |

SUI 2 |

3rd | 17 | |||

Notable victories

- Monaco Grand Prix (1): 1936

- Mille Miglia: (1): 1930

- Eifelrennen (3): 1931, 1932, 1935

- German Grand Prix (6): 1926, 1928, 1931, 1932, 1937, 1939

- GP Guipúzcoa (1): 1926

- Irish Grand Prix (1): 1930

- Avusrennen (1): 1931

- Monza Grand Prix (1): 1932

- Tripoli Grand Prix (1): 1935

- Coppa Arcebo (1) : 1938

- Lviv Grand Prix (1): 1932

- Mont Ventoux Hill Climb (2) : 1931, 1932

Notes

- Bolsinger and Becker (2002), p. 63

- Reuss (2006), p. 20

- Caracciola (1958), p. 1

- "Biography: Rudolf Caracciola (1901–1959)". Daimler Global Media Site. Daimler AG. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- Bolsinger and Becker (2002), p. 64

- Reuss (2006), pp. 18–19

- Caracciola (1958), p. 2

- Caracciola (1958), p. 215

- Caracciola (1958), p. 12

- Cimarosti (1986), pp. 65–66

- Caracciola (1958), p. 34

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 75

- Rendall (1993), p. 116

- Hilton (2005), p. 89

- Caracciola (1958), pp. 38–39

- Caracciola (1958), p. 40

- Bentley (1959), p. 31

- Bentley (1959), pp. 31–32

- Robert Blinkhorn (6 May 1999). "Lords of the 'Ring". 8W. FORIX. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 83

- Hilton (2005), p. 101

- Bentley (1959), pp. 32–33

- Rendall (1993), p. 124

- Hilton (2005), p. 104

- Bentley (1959), pp. 33–34

- Bentley (1959), p. 35

- Hilton (2005), p. 112

- Rendall (1993), p. 128

- Rendall (1993), p. 129

- Hilton (2005), p. 113

- Hilton (2005), pp. 115–116

- Hilton (2005), p. 116

- Bentley (1959), p. 36

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 90

- Rendall (1993), p. 131

- Caracciola (1958), pp. 55–56

- Caracciola (1958), p. 57

- Hilton (2005), pp. 118–120

- Rendall (1993), pp. 131–133

- Rendall (1993), p. 133

- Bentley (1959), p. 37

- Reuss (2006), pp. 30–31

- Bentley (1959), p. 38

- Caracciola (1958), p. 60

- Rendall (1993), p. 134

- Hilton (2005), p. 125

- Caracciola (1958), p. 62

- Leif Snellman (August 1999). "Mercedes' most successful driver". 8W. FORIX. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- Caracciola (1958), p. 67

- Reuss (2006), pp. 77–78

- Hilton (2005), p. 131

- Bentley (1959), p. 39

- Hilton (2005), p. 132

- Bolsinger and Becker (2002), p. 65

- Rendall (1993), p. 138

- Rendall (1993), p. 139

- Hilton (2005), p. 135

- Hilton (2005), pp. 137–138

- Bentley (1959), p. 42

- Hilton (2005), p. 138

- Hilton (2005), p. 141

- Hilton (2005), p. 147

- Bentley (1959), p. 44

- Caracciola (1958), p. 118

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 104

- Reuss (2006), p. 199

- Hilton (2005), pp. 151–152

- Hilton (2005), pp. 154–155

- Hilton (2005), p. 156

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 109

- Bentley (1959), pp. 44–45

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 110

- Reuss (2006), pp. 333–335

- Reuss (2006), pp. 337–338

- Bentley (1959), p. 46

- Hilton (2005), p. 158

- Hilton (2005), pp. 159–160

- Hilton (2005), p. 161

- Bentley (1959), pp. 46–47

- Bentley (1959), p. 47

- Hilton (2005), p. 164

- Bentley (1959), p. 48

- Caracciola (1958), p. 119

- Hilton (2005), p. 124

- Hilton (2005), p. 142

- Caracciola (1958), p. 120

- Reuss (2006), pp. 314–315

- Reuss (2006), pp. 211–212

- "Mercedes speed record cars of the 1930s". DaimlerChrysler. Classic Driver. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- Reuss (2006), p. 317

- Caracciola (1958), p. 127

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 116

- Hilton (2005), p. 177

- Bentley (1959), p. 49

- Hilton (2005), p. 179

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 122

- Hilton (2005), pp. 183–184

- Bentley (1959), p. 50

- Hilton (2005), p. 185

- Bentley (1959), pp. 50–53

- Reuss (2006), p. 369

- Richard Armstrong (11 July 2002). "Unfinished Symphony: Why the 1939 European Championship was never won". 8W. FORIX. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- Caracciola (1958), pp. 165–166

- Caracciola (1958), p. 168

- Caracciola (1958), p. 172

- Rendall (1993), p. 164

- Caracciola (1958), pp. 180–181

- Bentley (1959), p. 53

- A long way from home - Eoin Young, Motorsport Magazine, February 2009

- Bentley (1959), p. 54

- Boddy (1983), pp. 22–25

- Boddy (1983), p. 25

- Zane, Allan H. (Epilogue, 1961) in Caracciola (1958), pp. 212–213

- Rendall (1993), p. 216

- Zane, Allan H. (Epilogue, 1961) in Caracciola (1958), p. 214

- Reuss (2006), pp. 53–54

- Caracciola (1958), p. 163

- Reuss (2006), p. 115

- Reuss (2006), p. 113

- Reuss (2006), p. 187

- Reuss (2006), pp. 187–188

- Reuss (2006), p. 330

- Caracciola (1958), pp. 168–169

- Reuss (2006), p. 29

- Reuss (2006), p. 188

- Hilton (2005), p. 140

- Bentley (1959), p. 30

- Mattijs Diepraam; Felix Muelas; Leif Snellman (18 January 2000). "The Greatest Driver of the Century – The Poll Votes". 8W. FORIX. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- Ross Finlay (30 January 2001). "Rudi Caracciola: Part Two". CAR Keys. PDRonline. Archived from the original on 14 May 2006. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- Nick Garton (6 April 2008). "The Indianapolis Hall of Fame". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- "Rudolf Caracciola – International Motorsports Hall of Fame Inductee". International Motorsports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- "Remagen sightseeing". Remagen.de. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Remagen freut sich über seine neue Rheinpromenade". Remagen.de (in German). Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Noeth, Louise Ann Noeth (1999). "The 200 Mile Per Hour Club". Bonneville: The Fastest Place on Earth. Motorbooks. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7603-1372-5.

- "All Results of Rudolf Caracciola". racingsportscars.com. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "THE GOLDEN ERA – OF GRAND PRIX RACING". kolumbus.fi. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "Rudolf Caracciola". motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

References

- Bentley, John (1959). The Devil Behind Them: Nine Dedicated Drivers who Made Motor Racing History. London: Angus & Robertson.

- Boddy, William (1983). Mercedes-Benz 300SL: gull-wing & roadster, 3 litre, 6 cylinder. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-501-4.

- Bolsinger, Markus & Becker, Clauspeter (2002). Mercedes-Benz Silver Arrows. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-3-7688-1377-8.

- Caracciola, Rudolf (translated by Rock, Sigrid) (1961) [1958]. A Racing Car Driver's World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cimarosti, Adriano (translated by David Bateman Ltd) (1990) [1986]. The Complete History of Grand Prix Motor Racing. New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-69709-2.

- Hilton, Christopher (2005). Grand Prix Century: The First 100 Years of the World's Most Glamorous and Dangerous Sport. Somerset: Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-120-9.

- Rendall, Ivan (1993). The Chequered Flag: 100 Years of Motor Racing. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-83220-1.

- Reuss, Eberhard (translated by McGeoch, Angus) (2008) [2006]. Hitler's Motor Racing Battles: The Silver Arrows under the Swastika. Somerset: Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-476-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rudolf Caracciola. |

- Grand Prix History – Hall of Fame, Rudolf Caracciola

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

European Hill Climb Champion (for Sports Cars) 1930–1931 |

Succeeded by Hans Stuck |

| Preceded by Juan Zanelli |

European Hill Climb Champion (for Racing Cars) 1932 |

Succeeded by Carlo Felice Trossi |

| Preceded by Tazio Nuvolari (1932) |

European Drivers' Champion 1935 |

Succeeded by Bernd Rosemeyer |

| Preceded by Bernd Rosemeyer |

European Drivers' Champion 1937–1938 |

Succeeded by None (not awarded) |