Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era (/ˌsiː.nəˈzoʊ.ɪk, -noʊ-, ˌsɛn.ə-, ˌsɛn.oʊ-/ see-nə-ZOH-ik, -noh-, SEN-ə-, SEN-oh-)[1][2] meaning "new life" is the current and most recent of the three geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. It follows the Mesozoic Era and extends from 66 million years ago to the present day. It is generally believed to have started on the first day of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (also referred to as the K-Pg, or K-T, extinction event) when an asteroid hit the Earth.[3]

| Cenozoic Era 66–0 million years ago | |

Subdivisions of the Cenozoic -70 — – -60 — – -50 — – -40 — – -30 — – -20 — – -10 — – 0 — Phanerozoic Eon Graphic showing approximate timescale of the Cenozoic Era, and the time of the ** K-Pg mass extinction event at 65.8 Ma ago. Ordinate scale: millions of years (Ma) before present |

The Cenozoic is also known as the Age of Mammals, because the extinction of many groups allowed mammals to greatly diversify so that large mammals dominated the Earth. The continents also moved into their current positions during this era.

Early in the Cenozoic, following the K-Pg extinction event, most of the fauna was relatively small, and included small mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. From a geological perspective, it did not take long for mammals and birds to greatly diversify in the absence of the large reptiles that had dominated during the Mesozoic. Phorusrhacids, a group of avians known as the "terror birds", grew larger than the average human and were formidable predators. Mammals came to occupy almost every available niche (both marine and terrestrial), and some also grew very large, attaining sizes not seen in most of today's mammals.

The Earth's climate had begun a drying and cooling trend, culminating in the glaciations of the Pleistocene Epoch, and partially offset by the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.

Nomenclature

Cenozoic, meaning "new life," is derived from Greek καινός kainós "new," and ζωή zōḗ "life."[4] The era is also known as the Cænozoic, Caenozoic, or Cainozoic (/ˌkaɪnəˈzoʊɪk, ˌkeɪ-/).[5][6] The name "Cenozoic" (originally: "Kainozoic") was proposed in 1840 by the British geologist John Phillips (1800–1874).[7][8][9]

Divisions

The Cenozoic is divided into three periods: the Paleogene, Neogene, and Quaternary; and seven epochs: the Paleocene, Eocene, Oligocene, Miocene, Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene. The Quaternary Period was officially recognized by the International Commission on Stratigraphy in June 2009,[10] and the former term, Tertiary Period, became officially disused in 2004 due to the need to divide the Cenozoic into periods more like those of the earlier Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras.[11] The common use of epochs during the Cenozoic helps paleontologists better organize and group the many significant events that occurred during this comparatively short interval of time. Knowledge of this era is more detailed than any other era because of the relatively young, well-preserved rocks associated with it.

Paleogene

The Paleogene spans from the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, 66 million years ago, to the dawn of the Neogene, 23.03 million years ago. It features three epochs: the Paleocene, Eocene and Oligocene.

The Paleocene epoch lasted from 66 million to 56 million years ago. Modern placental mammals originated during this time. The Paleocene is a transitional point between the devastation that is the K-T extinction, and the rich jungle environment that is the Early Eocene. The Early Paleocene saw the recovery of the earth. The continents began to take their modern shape, but all the continents and the subcontinent of India were separated from each other. Afro-Eurasia was separated by the Tethys Sea, and the Americas were separated by the strait of Panama, as the isthmus had not yet formed. This epoch featured a general warming trend, with jungles eventually reaching the poles. The oceans were dominated by sharks[12] as the large reptiles that had once predominated were extinct. Archaic mammals filled the world such as creodonts (extinct carnivores, unrelated to existing Carnivora).

The Eocene Epoch ranged from 56 million years to 33.9 million years ago. In the Early-Eocene, species living in dense forest were unable to evolve into larger forms, as in the Paleocene. All known mammals were under 10 kilograms.[13] Among them were early primates, whales and horses along with many other early forms of mammals. At the top of the food chains were huge birds, such as Paracrax. The temperature was 30 degrees Celsius with little temperature gradient from pole to pole. In the Mid-Eocene, the Circumpolar-Antarctic current between Australia and Antarctica formed. This disrupted ocean currents worldwide and as a result caused a global cooling effect, shrinking the jungles. This allowed mammals to grow to mammoth proportions, such as whales which, by that time, had become almost fully aquatic. Mammals like Andrewsarchus were at the top of the food-chain. The Late Eocene saw the rebirth of seasons, which caused the expansion of savanna-like areas, along with the evolution of grass.[14][15] The end of the Eocene was marked by the Eocene-Oligocene extinction event, the European face of which is known as the Grande Coupure.

The Oligocene Epoch spans from 33.9 million to 23.03 million years ago. The Oligocene featured the expansion of grass which had led to many new species to evolve, including the first elephants, cats, dogs, marsupials and many other species still prevalent today. Many other species of plants evolved in this period too. A cooling period featuring seasonal rains was still in effect. Mammals still continued to grow larger and larger.[16]

Neogene

The Neogene spans from 23.03 million to 2.58 million years ago. It features 2 epochs: the Miocene, and the Pliocene.[17]

The Miocene epoch spans from 23.03 to 5.333 million years ago and is a period in which grass spread further, dominating a large portion of the world, at the expense of forests. Kelp forests evolved, encouraging the evolution of new species, such as sea otters. During this time, perissodactyla thrived, and evolved into many different varieties. Apes evolved into 30 species. The Tethys Sea finally closed with the creation of the Arabian Peninsula, leaving only remnants as the Black, Red, Mediterranean and Caspian Seas. This increased aridity. Many new plants evolved: 95% of modern seed plants evolved in the mid-Miocene.[18]

The Pliocene epoch lasted from 5.333 to 2.58 million years ago. The Pliocene featured dramatic climactic changes, which ultimately led to modern species of flora and fauna. The Mediterranean Sea dried up for several million years (because the ice ages reduced sea levels, disconnecting the Atlantic from the Mediterranean, and evaporation rates exceeded inflow from rivers). Australopithecus evolved in Africa, beginning the human branch. The isthmus of Panama formed, and animals migrated between North and South America during the great American interchange, wreaking havoc on local ecologies. Climatic changes brought: savannas that are still continuing to spread across the world; Indian monsoons; deserts in central Asia; and the beginnings of the Sahara desert. The world map has not changed much since, save for changes brought about by the glaciations of the Quaternary, such as the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and the Baltic sea.[19][20]

Quaternary

The Quaternary spans from 2.58 million years ago to present day, and is the shortest geological period in the Phanerozoic Eon. It features modern animals, and dramatic changes in the climate. It is divided into two epochs: the Pleistocene and the Holocene.

The Pleistocene lasted from 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago. This epoch was marked by ice ages as a result of the cooling trend that started in the Mid-Eocene. There were at least four separate glaciation periods marked by the advance of ice caps as far south as 40° N in mountainous areas. Meanwhile, Africa experienced a trend of desiccation which resulted in the creation of the Sahara, Namib, and Kalahari deserts. Many animals evolved including mammoths, giant ground sloths, dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, and most famously Homo sapiens. 100,000 years ago marked the end of one of the worst droughts in Africa, and led to the expansion of primitive humans. As the Pleistocene drew to a close, a major extinction wiped out much of the world's megafauna, including some of the hominid species, such as Neanderthals. All the continents were affected, but Africa to a lesser extent. It still retains many large animals, such as hippos.[21]

The Holocene began 11,700 years ago and lasts to the present day. All recorded history and "the Human history" lies within the boundaries of the Holocene epoch.[22] Human activity is blamed for a mass extinction that began roughly 10,000 years ago, though the species becoming extinct have only been recorded since the Industrial Revolution. This is sometimes referred to as the "Sixth Extinction". It is often cited that over 322 recorded species have become extinct due to human activity since the Industrial Revolution,[23][24] but the rate may be as high as 500 veterbrate species alone, the majority of which have occurred after 1900.[25]

Animal life

Early in the Cenozoic, following the K-Pg event, the planet was dominated by relatively small fauna, including small mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. From a geological perspective, it did not take long for mammals and birds to greatly diversify in the absence of the dinosaurs that had dominated during the Mesozoic. Some flightless birds grew larger than humans. These species are sometimes referred to as "terror birds," and were formidable predators. Mammals came to occupy almost every available niche (both marine and terrestrial), and some also grew very large, attaining sizes not seen in most of today's terrestrial mammals.

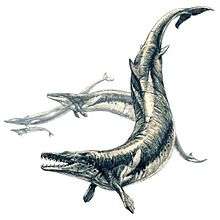

Early animals were the Entelodon, Paraceratherium (a hornless rhinoceros relative) and Basilosaurus (an early whale). The extinction of many large diapsid groups, such as flightless dinosaurs, Plesiosauria and Pterosauria allowed mammals and birds to greatly diversify and become the world's predominant fauna.

Tectonics

Geologically, the Cenozoic is the era when the continents moved into their current positions. Australia-New Guinea, having split from Pangea during the early Cretaceous, drifted north and, eventually, collided with South-east Asia; Antarctica moved into its current position over the South Pole; the Atlantic Ocean widened and, later in the era (2.8 million years ago), South America became attached to North America with the isthmus of Panama.

India collided with Asia 55 to 45 million years ago creating the Himalayas; Arabia collided with Eurasia, closing the Tethys Ocean and creating the Zagros Mountains, around 35 million years ago.[26]

The break-up of Gondwana in Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic times led to a shift in the river courses of various large African rivers including the Congo, Niger, Nile, Orange, Limpopo and Zambezi.[27]

Climate

In the Cretaceous, the climate was hot and humid with lush forests at the poles, there was no permanent ice and sea levels were around 300 metres higher than today. This continued for the first 10 million years of the Paleocene, culminating in the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum about 55.5 million years ago. Around 50 million years ago the earth entered a period of long term cooling. This was mainly due to the collision of India with Eurasia, which caused the rise of the Himalayas: the upraised rocks eroded and reacted with CO

2 in the air, causing a long-term reduction in the proportion of this greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Around 35 million years ago permanent ice began to build up on Antarctica.[28] The cooling trend continued in the Miocene, with relatively short warmer periods. When South America became attached to North America creating the Isthmus of Panama around 2.8 million years ago, the Arctic region cooled due to the strengthening of the Humboldt and Gulf Stream currents,[29] eventually leading to the glaciations of the Quaternary ice age, the current interglacial of which is the Holocene Epoch.

Recent analysis of the geomagnetic reversal frequency, oxygen isotope record, and tectonic plate subduction rate, which are indicators of the changes in the heat flux at the core mantle boundary, climate and plate tectonic activity, shows that all these changes indicate similar rhythms on million years' timescale in the Cenozoic Era occurring with the common fundamental periodicity of ∼13 Myr during most of the time.[30]

Life

During the Cenozoic, mammals proliferated from a few small, simple, generalized forms into a diverse collection of terrestrial, marine, and flying animals, giving this period its other name, the Age of Mammals, despite the fact that there are more than twice as many bird species as mammal species. The Cenozoic is just as much the age of savannas, the age of co-dependent flowering plants and insects, and the age of birds.[31] Grass also played a very important role in this era, shaping the evolution of the birds and mammals that fed on it. One group that diversified significantly in the Cenozoic as well were the snakes. Evolving in the Cenozoic, the variety of snakes increased tremendously, resulting in many colubrids, following the evolution of their current primary prey source, the rodents.

In the earlier part of the Cenozoic, the world was dominated by the gastornithid birds, terrestrial crocodiles like Pristichampsus, and a handful of primitive large mammal groups like uintatheres, mesonychids, and pantodonts. But as the forests began to recede and the climate began to cool, other mammals took over.

The Cenozoic is full of mammals both strange and familiar, including chalicotheres, creodonts, whales, primates, entelodonts, saber-toothed cats, mastodons and mammoths, three-toed horses, giant rhinoceros like Indricotherium, the rhinoceros-like brontotheres, various bizarre groups of mammals from South America, such as the vaguely elephant-like pyrotheres and the dog-like marsupial relatives called borhyaenids and the monotremes and marsupials of Australia.

See also

- Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–T boundary)

- Geologic time scale

- Late Cenozoic Ice Age

- Mesozoic

- Paleozoic

- Phanerozoic Eon

References

- "Cenozoic". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- "Cenozoic". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Gulick, Sean P. S.; Bralower, Timothy J.; Ormö, Jens; Hall, Brendon; Grice, Kliti; Schaefer, Bettina; Lyons, Shelby; Freeman, Katherine H.; Morgan, Joanna V.; Artemieva, Natalia; Kaskes, Pim; Graaff, Sietze J. de; Whalen, Michael T.; Collins, Gareth S.; Tikoo, Sonia M.; Verhagen, Christina; Christeson, Gail L.; Claeys, Philippe; Coolen, Marco J. L.; Goderis, Steven; Goto, Kazuhisa; Grieve, Richard A. F.; McCall, Naoma; Osinski, Gordon R.; Rae, Auriol S. P.; Riller, Ulrich; Smit, Jan; Vajda, Vivi; Wittmann, Axel; Scientists, the Expedition 364 (24 September 2019). "The first day of the Cenozoic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (39): 19342–19351. doi:10.1073/pnas.1909479116. PMC 6765282. PMID 31501350.

- "Cenozoic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "Cainozoic". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition, 1989

- Phillips, John (1840). "Palæozoic series". Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. vol. 17. London, England: Charles Knight and Co. pp. 153–154. From pp. 153–154: "As many systems or combinations of organic forms as are clearly traceable in the stratified crust of the globe, so many corresponding terms (as Palæozoic, Mesozoic, Kainozoic, &c.) may be made, … "

- Wilmarth, Mary Grace (1925). Bulletin 769: The Geologic Time Classification of the United States Geological Survey Compared With Other Classifications, accompanied by the original definitions of era, period and epoch terms. Washington, D.C., U.S.A.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 8.

- The evolution of the spelling of "Cenozoic" is reviewed in:

- Harland, W. Brian; Armstrong, Richard L.; Cox, Allen V.; Craig, Lorraine E.; Smith, David G.; Smith, Alan G. (1990). "The Chronostratic Scale". A Geologic Time Scale 1989. Cambridge, England, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 31.

- Phillips, John (1841). Figures and Descriptions of the Palæozoic Fossils of Cornwall, Devon, and West Somerset; …. London, England, U.K.: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans. p. 160.

- Gibbard, P. L.; Head, M. J.; Walker, M. J. C. (2010). "Formal ratification of the Quaternary System/Period and the Pleistocene Series/Epoch with a base at 2.58 Ma". Journal of Quaternary Science. 25 (2): 96–102. Bibcode:2010JQS....25...96G. doi:10.1002/jqs.1338.

- "International Stratigraphic Chart" (PDF).

- Royal Tyrrell Museum (28 March 2012), Lamniform sharks: 110 million years of ocean supremacy, retrieved 12 July 2017

- University of California. "Eocene Epoch". University of California.

- University of California. "Eocene Climate". University of California.

- National Geographic Society. "Eocene". National Geographic.

- University of California. "Oligocene". University of California.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Neogene". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- University of California. "Miocene". University of California.

- University of California. "Pliocene". University of California.

- Jonathan Adams. "Pliocene climate". Oak Ridge National Library. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015.

- University of California. "Pleistocene". University of California. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- University of California. "Holocene". University of California.

- Scientific American. "Sixth Extinction extinctions". Scientific American.

- IUCN. "Sixth Extinction". IUCN.

- Ceballos et al. (2015) (2015). "Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction". Science Advances. 1 (5): e1400253. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253. PMC 4640606. PMID 26601195.

- Allen, M. B.; Armstrong, H. A. (2008). "Arabia-Eurasia collision and the forcing of mid Cenozoic global cooling" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 265 (1–2): 52–58. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.04.021.

- Goudie, A.S. (2005). "The drainage of Africa since the Cretaceous". Geomorphology. 67 (3–4): 437–456. Bibcode:2005Geomo..67..437G. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.11.008.

- Dartnell, Lewis (2018). Origins:How the Earth Made Us. London, UK: Bodley Head. pp. 9–10, 40. ISBN 978-1-8479-2435-3.

- "How the Isthmus of Panama Put Ice in the Arctic". Oceanus Magazine.

- Chen, J.; Kravchinsky, V.A.; Liu, X. (2015). "The 13 million year Cenozoic pulse of the Earth". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 431: 256–263. Bibcode:2015E&PSL.431..256C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2015.09.033.

- "The Cenozoic Era".

Bibliography

- British Caenozoic Fossils, 1975, The Natural History Museum, London.

- Geologic Time, by Henry Roberts.

- After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals, by Donald R. Prothero, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-253-34733-6.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cainozoic. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cenozoic. |