Cabinetry

A cabinet is a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers for storing miscellaneous items. Some cabinets stand alone while others are built in to a wall or are attached to it like a medicine cabinet. Cabinets are typically made of wood (solid or with veneers or artificial surfaces), coated steel (common for medicine cabinets), or synthetic materials. Commercial grade cabinets, which differ in the materials used, are called casework, casegoods, or case furniture.

Cabinets usually have one or more doors on the front, which are mounted with door hardware, and occasionally a lock. Cabinets may have one or more doors, drawers, and/or shelves. Short cabinets often have a finished surface on top that can be used for display, or as a working surface, such as the countertops found in kitchens.

A cabinet intended to be used in a bedroom and with several drawers typically placed one above another in one or more columns intended for clothing and small articles is called a chest of drawers. A small bedside cabinet is more frequently called a nightstand or night table. A tall cabinet intended for clothing storage including hanging of clothes is called a wardrobe or an armoire, or (in some countries) a closet if built-in.

History

Before the advent of industrial design, cabinet makers were responsible for the conception and the production of any piece of furniture. In the last half of the 18th century, cabinet makers, such as Thomas Sheraton, Thomas Chippendale, Shaver and Wormley Bros. Cabinet Constructors, and George Hepplewhite, also published books of furniture forms. These books were compendiums of their designs and those of other cabinet makers. The most famous cabinetmaker before the advent of industrial design is probably André-Charles Boulle (11 November 1642 – 29 February 1732) and his legacy is known as "Boulle Work" and the École Boulle, a college of fine arts and crafts and applied arts in Paris, today bears testimony to his Art.[1]

With the industrial revolution and the application of steam power to cabinet making tools, mass production techniques were gradually applied to nearly all aspects of cabinet making, and the traditional cabinet shop ceased to be the main source of furniture, domestic or commercial. In parallel to this evolution there came a growing demand by the rising middle class in most industrialised countries for finely made furniture. This eventually resulted in a growth in the total number of traditional cabinet makers.

Before 1650, fine furniture was a rarity in Western Europe and North America. Generally, people did not need it and for the most part could not afford it. They made do with simple but serviceable pieces.

The arts and craft movement which started in the United Kingdom in the middle of the 19th century spurred a market for traditional cabinet making, and other craft goods. It rapidly spread to the United States and to all the countries in the British Empire. This movement exemplified the reaction to the eclectic historicism of the Victorian era and to the 'soulless' machine-made production which was starting to become widespread. During this time, cabinetry was said to be one of the most noble and admirable skills by nearly one fourth of the population of the United Kingdom, and 31% of those who believed this strived for their children to learn the art of cabinetry.

After World War II woodworking became a popular hobby among the middle classes. The more serious and skilled amateurs in this field now turn out pieces of furniture which rival the work of professional cabinet makers. Together, their work now represents but a small percentage of furniture production in any industrial country, but their numbers are vastly greater than those of their counterparts in the 18th century and before.

Schools of design

Scandinavian

This style of design is typified by clean horizontal and vertical lines. Compared to other designs there is a distinct absence of ornamentation. While Scandinavian design is easy to identify, it is much more about the materials than the design.

French Provincial

This style of design is very ornate. French Provincial objects are often stained or painted, leaving the wood concealed. Corners and bevels are often decorated with gold leaf or given some other kind of gilding. Flat surfaces often have artwork such as landscapes painted directly on them. The wood used in French provincial varied, but was often originally beech.[3]

Early American Colonial

This design emphasises both form and materials. Early American chairs and tables are often constructed with turned spindles and chair backs often constructed using steaming to bend the wood. Wood choices tend to be deciduous hardwoods with a particular emphasis on the wood of edible or fruit-bearing trees such as cherry or walnut.[4]

Rustic

The rustic style of design sometimes called "log furniture" or "log cabin" is the least finished. Design is very utilitarian yet seeks to feature not only the materials used but in, as much as possible, how they existed in their natural state. For example, a table top may have what is considered a "live edge" that allows you to see the original contours of the tree that it came from. It also often uses whole logs or branches including the bark of the tree. Rustic furniture is often made from pine, cedar, fir and spruce. Also see Adirondack Architecture.

Mission Style

Mission Design is characterized by straight, thick horizontal and vertical lines and flat panels. The most common material used in Mission furniture is oak. For early mission cabinetmakers, the material of choice was white oak, which they often darkened through a process known as "fuming".[5] Hardware is often visible on the outside of the pieces and made of black iron. It is a style that became popular in the early 20th century; popularized by designers in the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveaux movements.

Oriental

Also known as Asian Design, this style of furniture is characterized by its use of materials such as bamboo and rattan. Red is a frequent color choice along with landscape art and Chinese or other Asian language characters on the pieces.

Shaker

Shaker furniture design is focused on function and symmetry. Because it is so influenced by an egalitarian religious community and tradition it is rooted in the needs of the community versus the creative expression of the designer. Like Early American and Colonial design, Shaker craftsmen often chose fruit woods for their designs. Pieces reflect a very efficient use of materials.

Types of cabinetry

The fundamental focus of the cabinet maker is the production of cabinetry. Although the cabinet maker may also be required to produce items that would not be recognized as cabinets, the same skills and techniques apply.

A cabinet may be built-in or free-standing. A built-in cabinet is usually custom made for a particular situation and it is fixed into position, on a floor, against a wall, or framed in an opening. For example, modern kitchens are examples of built-in cabinetry. Free-standing cabinets are more commonly available as off-the-shelf items and can be moved from place to place if required. Cabinets may be wall hung or suspended from the ceiling. Cabinet doors may be hinged or sliding and may have mirrors on the inner or outer surface.

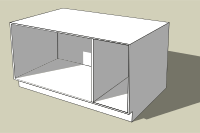

Cabinets may have a face frame or may be of frameless construction (also known as European or euro-style). Face frame cabinets have a supporting frame attached to the front of the cabinet box. This face frame is usually 1 1⁄2 inches (4 cm) in width. Mounted on the cabinet frame is the cabinet door. In contrast, frameless cabinet have no such supporting front face frame, the cabinet doors attach directly to the sides of the cabinet box. The box's side, bottom and top panels are usually 5⁄8 to 3⁄4 inch (15 to 20 mm) thick, with the door overlaying all but 1⁄16 inch (2 mm) of the box edge.[6] Modern cabinetry is often frameless and is typically constructed from man-made sheet materials, such as plywood, chipboard or medium-density fibreboard (MDF). The visible surfaces of these materials are usually clad in a timber veneer, plastic laminate, or other material. They may also be painted.

Cabinet components

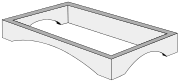

Bases

Cabinets which rest on the floor are supported by some base. This base could be a fully enclosed base (i.e. a plinth), a scrolled based, bracket feet or it could be a set of legs.

Adjustable feet

A type of adjustable leg has been adopted from the European cabinet system which offers several advantages. First off, in making base cabinets for kitchens, the cabinet sides would be cut to 34½ inches, yielding four cabinet side blanks per 4 foot by 8 foot sheet. Using the adjustable feet, the side blanks are cut to 30 inches, thus yielding six cabinet side per sheet.

These feet can be secured to the bottom of the cabinet by having the leg base screwed onto the cabinet bottom. They can also be attached by means of a hole drilled through the cabinet bottom at specific locations. The legs are then attached to the cabinet bottom by a slotted, hollow machine screw. The height of the cabinet can be adjusted from inside the cabinet, simply by inserting a screwdriver into the slot and turning to raise or lower the cabinet. The holes in the cabinet are capped by plastic inserts, making the appearance more acceptable for residential cabinets. Using these feet, the cabinets need not be shimmed or scribed to the floor for leveling. The toe kick board is attached to the cabinet by means of a clip, which is either screwed onto the back side of the kick board, or a barbed plastic clip is inserted into a saw kerf, also made on the back side of the kick board. This toe kick board can be made to fit each base cabinet, or made to fit a run of cabinets.[7]

Kitchen cabinets, or any cabinet generally at which a person may stand, usually have a fully enclosed base in which the front edge has been set back 75 mm or so to provide room for toes, known as the kick space. A scrolled base is similar to the fully enclosed base but it has areas of the base material removed, often with a decorative pattern, leaving feet on which the cabinet stands. Bracket feet are separate feet, usually attached in each corner and occasionally for larger pieces in the middle of the cabinet.

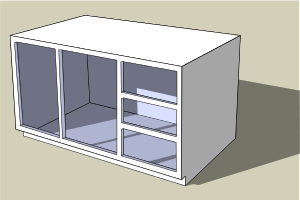

Compartments

A cabinet usually has at least one compartment. Compartments may be open, as in open shelving; they may be enclosed by one or more doors; or they may contain one or more drawers. Some cabinets contain secret compartments, access to which is generally not obvious.

Modern cabinets employ many more complicated means (relative to a simple shelf) of making browsing lower cabinets more efficient and comfortable. One example is the lazy susan, a shelf which rotates around a central axis, allowing items stored at the back of the cabinet to be brought to the front by rotating the shelf. These are usually used in corner cabinets, which are larger and deeper and have a greater "dead space" at the back than other cabinets.

Cabinet insert hardware

An alternative to the lazy susan, particularly in base cabinets, is the blind corner cabinet pull out unit. These pull out and turn, making the attached shelving unit slide into the open area of the cabinet door, thus making the shelves accessible to the user. These units make usable what was once dead space.

Other insert hardware includes such items as mixer shelves that pull out of a base cabinet and spring into a locked position at counter height. This hardware aids in lifting these somewhat heavy mixers and assists with positioning the unit for use. More and more components are being designed to enable specialized hardware to be used in standard cabinet carcasses.

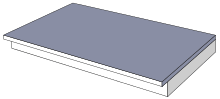

Tops

Most cabinets incorporate a top of some sort. In many cases, the top is merely to enclose the compartments within and serves no other purpose—as in a wall hung cupboard for example. In other cabinets, the top also serves as a work surface—a kitchen countertop for example.

See also

- List of furniture designers

- List of furniture types

- Woodworking

- Amish furniture

- Ébéniste (French for "cabinet-maker")

- Tansu

References

- Specific citations

-

- Monika Kuhnke (2000). "Cenny dar dla zwycięzcy spod Wiednia". icons.pl (in Polish). valuable, priceless, lost. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - French Furniture - Andre Saglio. Google Books. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- "Early American furniture - Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- The Stickley Brothers: The Quest for an American Voice - Michael E. Clark, Jill Thomas-Clark. Google Books. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- "Refinishing and Upgrading Kitchen Cabinets". CabinetsQandA.com. 2010. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- "Base Cabinet Construction Sketch". ProWoodworkingTips.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-05. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- General references

- Lee Jesberger (2007). Pro Woodworking Tips.com.

- Ernest Joyce (1970). Encyclopedia of Furniture Making. Revised and expanded by Alan Peters (1987). Sterling Publishing. ISBN 0-8069-6440-5 (Original edition), ISBN 0-8069-7142-8 (Paperback)

- John L. Feirer (1988). Cabinetmaking and Millwork, Fifth Edition. Glencoe Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-675950-0

External links

- Kenny, Peter M.; Safford, Frances Gruber; Vincent, Gilbert T. "American kasten : the Dutch-style cupboards of New York and New Jersey, 1650-1800" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries.; Register of Cabinetmakers, PDF: https://www.museenkoeln.de/Kunst-und-Museumsbibliothek/download/kittel%5B%5D (Kunst- und Museumsbibliothek der Stadt Köln, Kunstdokumentation Werner Kittel, Department of Furniture)