Long March 5

Long March 5 (LM-5, CZ-5, or Chang Zheng 5) is a Chinese heavy lift launch system developed by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT). It is the first Chinese launch vehicle designed from the ground up to focus on non-hypergolic liquid rocket propellants.[8] There are currently two CZ-5 variants: CZ-5 and CZ-5B. The maximum payload capacities of the base variant is ~25,000 kilograms (55,000 lb) to LEO[9] and ~14,000 kilograms (31,000 lb) to GTO.[10] The Long March 5 roughly matches the capabilities of American EELV heavy-class vehicles such as the Delta IV Heavy. It is currently the most powerful member of the Long March rocket family and the world's third most powerful orbital launch vehicle currently in operation, trailing Delta IV Heavy and Falcon Heavy.[11]

Long March 5 Y2 transporting to launch site | |

| Function | Heavy launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | CALT |

| Country of origin | China |

| Size | |

| Height | 56.97 metres (186.9 ft) |

| Diameter | 5 metres (16 ft) |

| Mass | 878,556 kilograms (1,936,884 lb) |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO (200 km × 400 km × 42°) | 25,000 kilograms (55,000 lb)[1][2] |

| Payload to GTO | 14,400 kilograms (31,700 lb)[3][4] |

| Payload to TLI | 8,800 kilograms (19,400 lb)-9,400 kilograms (20,700 lb) |

| Payload to GEO | 6,000 kilograms (13,000 lb) |

| Payload to SSO | 15,000 kilograms (33,000 lb)(700km) 6,700 kilograms (14,800 lb)(2000km) |

| Payload to MTO | 13,000 kilograms (29,000 lb) |

| Payload to TMI | 6,000 kilograms (13,000 lb) |

| Associated rockets | |

| Family | Long March |

| Comparable | |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Active |

| Launch sites | Wenchang, LC-1 |

| Total launches | 5

|

| Successes | 4

|

| Failures | 1 (CZ-5)

|

| First flight | |

| Last flight | Active |

| Boosters – CZ-5-300 | |

| No. boosters | 4 |

| Length | 27.6 m (91 ft) |

| Diameter | 3.35 m (11.0 ft) |

| Gross mass | 155,700 kg (343,300 lb) |

| Propellant mass | 144,000 kg (317,000 lb) |

| Engines | 2 × YF-100 |

| Thrust | SL: 2,400 kN (540,000 lbf) Vac.: 2,680 kN (600,000 lbf) |

| Total thrust | 9,600 kN (2,200,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | SL: 300 seconds (2.9 km/s) Vac: 335 seconds (3.29 km/s) |

| Burn time | 180 seconds |

| Fuel | RP-1 / LOX |

| First stage – CZ-5-500 | |

| Length | 31.7 m (104 ft) |

| Diameter | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Gross mass | 175,600 kg (387,100 lb) |

| Propellant mass | 158,300 kg (349,000 lb) |

| Engines | 2 × YF-77 |

| Thrust | SL: 1,020 kN (230,000 lbf) Vac: 1,400 kN (310,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | SL: 310.2 seconds (3.042 km/s) Vac: 430 seconds (4.2 km/s) |

| Burn time | 480 seconds |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

| Second stage – CZ-5-HO | |

| Length | 10.6 m (35 ft) |

| Diameter | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Gross mass | 25,000 kg (55,000 lb) |

| Propellant mass | 17,100 kg (37,700 lb) |

| Engines | 2 × YF-75D |

| Thrust | 176.52 kN (39,680 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 442 seconds (4.33 km/s) |

| Burn time | 700 seconds |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

| Third stage – YZ-2 (Optional) | |

| Diameter | 3.8 metres (12 ft) |

| Engines | 2 x YF-50D |

| Thrust | 6.5 kN (1,500 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 316 seconds (3.10 km/s) |

| Burn time | 1105 seconds |

| Fuel | N2O4 / UDMH |

The first CZ-5 launched from Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Center on 3 November 2016 and placed its payload in a suboptimal but workable initial orbit.[12] The second CZ-5 rocket, launched on 2 July 2017, failed due to an engine problem in the first stage.

After an interval of almost two and a half years, the Long March 5 vehicle's return to flight mission (third launch) successfully occurred on 27 December 2019 with the launch and placement of the experimental Shijian-20 communications satellite into geostationary transfer orbit, thereby opening the way for China to proceed with its planned Tianwen 1 Mars mission, lunar Chang'e 5 sample-return mission, and modular space station[7], all of which require the lifting capabilities of a heavy lift launch vehicle.

Development

Since 2010, Long March launches (all versions) have made up 15–25% of the global launch totals. Growing domestic demand for launch services has also allowed China's state launch provider to maintain a healthy manifest. Additionally, China had been able to secure some international launch contracts by offering package deals that bundle launch vehicles with Chinese satellites, thereby circumventing the effects of U.S. embargo.[13]

China's main objective for initiating the new CZ-5 program in 2007 was in anticipation of its future requirement for larger LEO and GTO payload capacities during the next 20–30 years period. Formal approval of the Long March 5 program occurred in 2007 following two decades of feasibility studies when funding was finally granted by the Chinese government. At the time, the new rocket was expected to be manufactured at a facility in Tianjin, a coastal city near Beijing[9], while launch was expected to occur at the new Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site in the southernmost island province of Hainan.[9]

In July 2012, a new 1200 kN thrust LOX/kerosene engine to be used on the Long March 5 boosters was test-fired by China.[10][14]

The first photos of a CZ-5, undergoing tests, were released in March 2015.[15]

The first production CZ-5 was shipped from the port of Tianjin in North China to Wenchang Satellite Launch Center on Hainan Island on 20 September 2015 for launch rehearsals.[16]. The maiden flight of the CZ-5 was initially scheduled for 2014, but this subsequently slipped to 2016.[17]

The final production and testing of the first CZ-5 rocket to be launched into orbit were completed at its Tianjin manufacturing facility on or about 16 August 2016 and the various segments of the rocket were shipped to the launch center on Hainan island shortly thereafter.[18]

Design and specifications

The chief designer of CZ-5 is Li Dong (Chinese: 李东) of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT). The CZ-5 family include three primary modular core stages of 5.2-m diameter (maximum). The total length of the vehicle is 60.5 metres and its weight at launch is 643 tons, with a thrust of 833.8 tons. Boosters of various capabilities and diameters ranging from 2.25 metres to 3.35 metres would be assembled from three modular core stages and strap-on stages. The first stage and boosters would have a choice of engines that use different liquid rocket propellants: 1200 kN thrust LOX / kerosene engines or 500 kN thrust LOX / LH2. The upper stage would use improved versions of the YF-75 engine.

Engine development began in 2000–2001, with testing directed by the China National Space Administration (CNSA) commencing in 2005. Versions of both new engines, the YF-100 and the YF-77, had been successfully tested by mid-2007.

The CZ-5 series can deliver ~23 tonnes payload to LEO or ~14 tonnes payload to GTO (geosynchronous transfer orbit).[19] It will replace the CZ-2, CZ-3, and CZ-4 series in service, as well as provide new capabilities not possessed by the previous Long March rocket family. The CZ-5 launch vehicle would consist of a 5.0-m diameter core stage and four 3.35-m diameter strap-on boosters, which would be able to send a ~22 tonne payload to low earth orbit (LEO).

Six CZ-5 variants were originally planned,[20][21] but the light variants were cancelled in favor of CZ-6 and CZ-7 family launch vehicles.

- Active

| Version | CZ-5 | CZ-5B |

|---|---|---|

| Boosters | 4 × CZ-5-300, 2 × YF-100 | 4 × CZ-5-300, 2 × YF-100 |

| First stage | CZ-5-500, 2 × YF-77 | CZ-5-500, 2 × YF-77 |

| Second stage | CZ-5-HO, 2 × YF-75D | -- |

| Third stage (optional) | Yuanzheng-2 | -- |

| Thrust (at ground) | 10565 KN | 10565 KN |

| Launch weight | 867,000 kg | 849,000 kg [22] |

| Height | 56.97 m | 53.66 m |

| Payload (LEO 200 km) | -- | ~25,000 kg [23] |

| Payload (GTO) | ~14,000 kg [23] | -- |

| References:[19] | ||

- Proposed[23]

| Version | CZ-5-200 | CZ-5-320 | CZ-5-522 | CZ-5-540 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boosters | -- | 2 × CZ-5-200, YF-100 | 2 × CZ-5-200, YF-100; 2 × CZ-5-300, 2 × YF-100 | 4 × CZ-5-200, YF-100 |

| First stage | CZ-5-200, YF-100 | CZ-5-300, 2 × YF-100 | CZ-5-500, 2 × YF-77 | CZ-5-500, 2 × YF-77 |

| Second stage | CZ-YF-73, YF-73 | CZ-5-KO, | CZ-5-HO, 2 × YF-75D | CZ-5-HO, 2 × YF-75D |

| Third stage (not used for LEO) | -- | CZ-5-HO, YF-75 | -- | -- |

| Thrust (at ground) | 1.34 MN | 7.2 MN | 8.24 MN | 5.84 MN |

| Launch weight | 82,000 kg | 420,000 kg | 630,000 kg | 470,000 kg |

| Height (maximal) | 33 m | 55 m | 58 m | 53 m |

| Payload (LEO 200 km) | 1500 kg | 10,000 kg | 20,000 kg | 10,000 kg |

| Payload (GTO) | -- | 6000 kg | 11,000 kg | 6000 kg |

| References:[9] | ||||

Notable launches

First flight

The launch was planned to take place at around 10:00 UTC on 3 November 2016, but several issues, involving an oxygen vent and chilling of the engines, were detected during the preparation, causing a delay of nearly three hours. The final countdown was interrupted three times due to problems with the flight control computer and the tracking software.[24] The rocket finally launched at 12:43 UTC.[25] According to an internet blogger on the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo, a minor problem occurred during flight and the rocket put the YZ-2 upper stage and satellite into an orbit that was less accurate than expected. However, the trajectory was corrected with the YZ-2 upper stage and the payload was inserted into the desired orbit.[26]

Second flight

Its second launch on 2 July 2017 experienced an anomaly shortly after launch and was switched to an alternate, gentler trajectory. However, it was declared a failure 45 minutes into the flight.[27][28] The cause of the failure was confirmed by CASC and related to an anomaly which happened on one of the YF-77 engines in the first stage.[29]

Return to flight (third flight)

Investigations revealed the source of the second flight's failure to be located in one of the core stage's YF-77 engines (specifically, in the oxidizer's turbo-pump[7]). A redesigned YF-77 engine was test-fired in 2018 by China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC).[30] At the time, the launch date for the vehicle's return to flight was estimated to be in January 2019.[31] However, new problems in the redesigned engine were discovered during further testing, causing additional delays. After repeated cancellations and delays, the launch date for the return to flight mission Y3, was set for 27 December 2019.[32]

The Y3 mission of the Long March 5 program was launched on 27 December 2019, at about 12:45 UTC from the Wenchang Satellite Launch Center in Hainan, China. CASC declared the mission a success within an hour of launch, after the Shijian-20 communications satellite was placed in geostationary transfer orbit, thus marking the Long March 5 program's return to flight.[7]

Fourth flight (CZ-5B)

The fourth flight of the Long March 5 program also marked the debut of the CZ-5B variant. The CZ-5B variant is basically equivalent to the Long March 5 core stage with its four strapped-on liquid-fueled boosters; in place of the usual second stage of the base configuration, it is anticipated that heavier low Earth orbit payloads, such as components of the future modular space station, would be carried by the 5B variant.

The first flight of the 5B variant ("Y1 mission") carried an uncrewed prototype of China's future deep space crewed spacecraft, and, as a secondary payload, an experimental cargo return craft: the Flexible Inflatable Cargo Re-entry Vehicle. The Y1 mission was launched on 5 May 2020, at 10:00 UTC from the Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site in Hainan Island. CASC declared the launch a success after the payloads were placed in low Earth orbit.[33][34]

The flight's secondary payload, the experimental cargo return craft, malfunctioned during its return to Earth on 6 May 2020.[35] Nevertheless, the return capsule of the prototype next-generation crewed spacecraft, the flight's primary payload, successfully returned to the Dongfeng landing site in north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region at 05:49 UTC, on 8 May 2020. The prototype spacecraft flew in orbit for two days and 19 hours and carried out a series of apparently successful experiments and technology verifications.[36]

The Y1 mission's core stage, with a mass of about 20000 kg, was in an orbit with an inclination of 41.1° and eventually made an uncontrolled reentry at 15:33 UTC on 11 May 2020 over 20° W 20° N, as it flew over the Atlantic Ocean heading towards Nouakchott, Mauritania (some debris apparently survived reentry and landed in Côte d'Ivoire).[37] The Y1 mission's core stage may be the most massive object to make an uncontrolled re-entry since the Soviet Union's Salyut 7 space station in 1991 and the United States' Skylab in 1979.[38]

List of launches

Past launches

| Flight № | Date (UTC) | Variant | Launch site | Upper stage | Payload | Orbit | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | 3 November 2016 12:43 [6] |

5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | YZ-2 | Shijian 17 | GEO | Success |

| Y2 | 2 July 2017 11:23 |

5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Shijian 18 | GTO | Failure |

| Y3 | 27 December 2019 12:45 |

5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Shijian 20 | GTO | Success |

| 5B-Y1 | 5 May 2020 10:00 [34][39] |

5B | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Next-generation crewed spacecraft (success) Test of flexible inflatable cargo re-entry vehicle (failure) |

LEO | Success |

| Y4 | 23 July 2020 04:41 [40] |

5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Tianwen-1 Mars orbiter, lander and rover | TMI | Success |

Planned launches

| Flight № | Date (UTC) | Variant | Launch site | Upper stage | Payload | Orbit | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y5 | Q4 2020 [39] | 5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Chang'e 5, lunar sample-return | TLI | Planned |

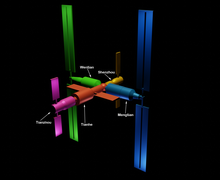

| 5B-Y2 | Q2 2021 [39] | 5B | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Tianhe, space station core module | LEO | Planned |

| 5B-Y3 | 2021 [39] | 5B | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Wentian, space station experiment module 1 | LEO | Planned |

| 5B-Y4 | 2022 [39] | 5B | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Mengtian, space station experiment module 2 | LEO | Planned |

| Y6 | 2024 [39] | 5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Chang'e 6, lunar sample-return | TLI | Planned |

| 5B-Y5 | 2024 [39] | 5B | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | Xun Tian, space telescope | LEO | Planned |

| Y7 | 2024 [39] | 5 | Wenchang, LC-1 | None | SPORT (Solar Polar Orbit Telescope) | Heliocentric | Planned |

See also

- Comparison of orbital launchers families

- Comparison of orbital launch systems

- Expendable launch system

- Lists of rockets

References

- Mu, Xuequan. "China's largest carrier rocket Long March-5 makes new flight". Xinhuanet. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Lifang. "China to launch Long March-5B rocket in 2019". Xinhuanet. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Mu, Xuequan. "China's largest carrier rocket Long March-5 makes new flight". Xinhuanet. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Lifang. "China to launch Long March-5B rocket in 2019". Xinhuanet. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Successful Launch of Long March-5 Rocket". CCTV. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "China conducts Long March 5 maiden launch". NASASpaceflight.com. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Jones, Andrew. "Successful Long March 5 launch opens way for China's major space plans". spacenews.com. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Chinese Long March 5 rocket". AirForceWorld.com. 12 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- "Long March 5 Will Have World's Second Largest Carrying Capacity". Space Daily. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Space.com staff (30 July 2012). "China Tests Powerful Rocket Engine for New Booster". Space.com.

- Mosher, Dave. "China's wildly ambitious future in space just got a big boost with the successful launch of its new heavy-lift rocket". Business Insider. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Foust, Jeff. "Long March 5 launch fails". Spacenews. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Henry, Caleb (22 August 2017). "Back-to-back commercial satellite wins leave China Great Wall hungry for more". SpaceNews.

- Additional engine test-firings took place in July 2013.David, Leonard (15 July 2013). "China Long March 5 Rocket Engine Test". Space.com.

Chinese Rocket Engine Test a Big Step for Space Station Project

- Errymath. "First released picture of Long March 5 (CZ-5) Heavy Rocket". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "China to rehearse new carrier rocket for lunar mission". English.news.cn. 20 September 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- spaceflightnow Archived 24 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 30 September 2016

- "Chinese Long March 5 rocket ready to launch". AirForceWorld.com. 17 August 2015. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Xiang, Meng; Tongyu, Li. "The New Generation Launch Vehicles In China" (PDF). International Astronautical Federation. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Harvey, Brian (2013). China in Space: The Great Leap Forward. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 364. ISBN 978-1-4614-5043-6.

- Zhao, Lei (21 April 2016). "6 versions of LongMarch 5 rocket inworks". usa.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- http://french.peopledaily.com.cn/n3/2020/0506/c31357-9687050.html - 6 May 2020 - 8 May 2020

- Kyle, Ed. "CZ-5 Data Sheet".

- 罪恶大天使 (4 November 2016). "长征五号首飞纪实" [The first flight of the Long March 5]. Sina Weibo (in Chinese). Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "China launches Long March 5, one of the world's most powerful rockets". SpaceFlightNow.com. 3 November 2016.

- 大脚丫的汤婆婆 (4 November 2016). "远征二号是两次点火,第一次近地点附近点火..." [Yuanzheng-2 ignited twice, with the first ignition near the perigee...]. Sina Weibo (in Chinese). Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Chinese rocket launch fails after liftoff". CNN. 3 July 2017.

- Barbosa, Rui C. (2 July 2017). "Long March 5 suffers failure with Shijian-18 launch". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Casc Confirms Cause Of Long March 5 Failure". Aviation Week. 2 March 2018.

- "China test fires YF-77 rocket engine ahead of return-to-flight of Long March 5". Global Times. 28 February 2018.

- "Chinese Long March 5 heavy-lift launcher ready for January 2019 comeback flight". GBTimes.com. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- https://m.weibo.cn/detail/4443949391356221

- "China's first Long March 5B rocket launches on crew capsule test flight". SpaceFlightNow.com. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Clark, Stephen (24 January 2020). "Prototypes for new Chinese crew capsule and space station arrive at launch site". SpaceFlightNow.com. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/05/06/experimental-chinese-cargo-return-capsule-malfunctions-during-re-entry/ - 6 May 2020

- http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-05/08/c_139041254.htm - 8 May 2020 - 9 May 2020

- "Reentry". www.planet4589.org. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "U.S. military tracking unguided re-entry of large Chinese rocket". spaceflightnow.com. SFN. 9 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Pietrobon, Steven (30 January 2019). "Chinese Launch Manifest". Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Jones, Andrew (23 July 2020). "Tianwen-1 launches for Mars, marking dawn of Chinese interplanetary exploration". spacenews.com. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

External links