Glycoside

In chemistry, a glycoside /ˈɡlaɪkəsaɪd/ is a molecule in which a sugar is bound to another functional group via a glycosidic bond. Glycosides play numerous important roles in living organisms. Many plants store chemicals in the form of inactive glycosides. These can be activated by enzyme hydrolysis,[1] which causes the sugar part to be broken off, making the chemical available for use. Many such plant glycosides are used as medications. Several species of Heliconius butterfly are capable of incorporating these plant compounds as a form of chemical defense against predators.[2] In animals and humans, poisons are often bound to sugar molecules as part of their elimination from the body.

In formal terms, a glycoside is any molecule in which a sugar group is bonded through its anomeric carbon to another group via a glycosidic bond. Glycosides can be linked by an O- (an O-glycoside), N- (a glycosylamine), S-(a thioglycoside), or C- (a C-glycoside) glycosidic bond. According to the IUPAC, the name "C-glycoside" is a misnomer; the preferred term is "C-glycosyl compound".[3] The given definition is the one used by IUPAC, which recommends the Haworth projection to correctly assign stereochemical configurations.[4] Many authors require in addition that the sugar be bonded to a non-sugar for the molecule to qualify as a glycoside, thus excluding polysaccharides. The sugar group is then known as the glycone and the non-sugar group as the aglycone or genin part of the glycoside. The glycone can consist of a single sugar group (monosaccharide) or several sugar groups (oligosaccharide).

The first glycoside ever identified was amygdalin, by the French chemists Pierre Robiquet and Antoine Boutron-Charlard, in 1830.[5]

Related compounds

Molecules containing an N-glycosidic bond are known as glycosylamines and are not discussed in this article. (Many authors in biochemistry call these compounds N-glycosides and group them with the glycosides; this is considered a misnomer, and discouraged by IUPAC.) Glycosylamines and glycosides are grouped together as glycoconjugates; other glycoconjugates include glycoproteins, glycopeptides, peptidoglycans, glycolipids, and lipopolysaccharides.

Chemistry

Much of the chemistry of glycosides is explained in the article on glycosidic bonds. For example, the glycone and aglycone portions can be chemically separated by hydrolysis in the presence of acid and can be hydrolyzed by alkali. There are also numerous enzymes that can form and break glycosidic bonds. The most important cleavage enzymes are the glycoside hydrolases, and the most important synthetic enzymes in nature are glycosyltransferases. Genetically altered enzymes termed glycosynthases have been developed that can form glycosidic bonds in excellent yield.

There are many ways to chemically synthesize glycosidic bonds. Fischer glycosidation refers to the synthesis of glycosides by the reaction of unprotected monosaccharides with alcohols (usually as solvent) in the presence of a strong acid catalyst. The Koenigs-Knorr reaction is the condensation of glycosyl halides and alcohols in the presence of metal salts such as silver carbonate or mercuric oxide.

Classification

Glycosides can be classified by the glycone, by the type of glycosidic bond, and by the aglycone.

By glycone/presence of sugar

If the glycone group of a glycoside is glucose, then the molecule is a glucoside; if it is fructose, then the molecule is a fructoside; if it is glucuronic acid, then the molecule is a glucuronide; etc. In the body, toxic substances are often bonded to glucuronic acid to increase their water solubility; the resulting glucuronides are then excreted.

By type of glycosidic bond

Depending on whether the glycosidic bond lies "below" or "above" the plane of the cyclic sugar molecule, glycosides are classified as α-glycosides or β-glycosides. Some enzymes such as α-amylase can only hydrolyze α-linkages; others, such as emulsin, can only affect β-linkages.

There are four type of linkages present between glycone and aglycone:

- C-linkage/glycosidic bond, "nonhydrolysable by acids or enzymes"

- O-linkage/glycosidic bond

- N-linkage/glycosidic bond

- S-linkage/glycosidic bond

By aglycone

Glycosides are also classified according to the chemical nature of the aglycone. For purposes of biochemistry and pharmacology, this is the most useful classification.

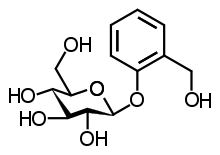

Alcoholic glycosides

An example of an alcoholic glycoside is salicin, which is found in the genus Salix. Salicin is converted in the body into salicylic acid, which is closely related to aspirin and has analgesic, antipyretic, and antiinflammatory effects.

Anthraquinone glycosides

These glycosides contain an aglycone group that is a derivative of anthraquinone. They have a laxative effect. They are mainly found in dicot plants except the family Liliaceae which are monocots. They are present in senna, rhubarb and Aloe species. Anthron and anthranol are reduced forms of anthraquinone.

Coumarin glycosides

Here, the aglycone is coumarin or a derivative. An example is apterin which is reported to dilate the coronary arteries as well as block calcium channels. Other coumarin glycosides are obtained from dried leaves of Psoralea corylifolia.

Chromone glycosides

In this case, the aglycone is called benzo-gamma-pyrone.

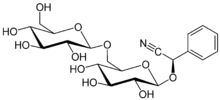

Cyanogenic glycosides

In this case, the aglycone contains a cyanohydrin group. Plants that make cyanogenic glycosides store them in the vacuole, but, if the plant is attacked, they are released and become activated by enzymes in the cytoplasm. These remove the sugar part of the molecule, allowing the cyanohydrin structure to collapse and release toxic hydrogen cyanide. Storing them in inactive forms in the vacuole prevents them from damaging the plant under normal conditions.[6]

Along with playing a role in deterring herbivores, in some plants they control germination, bud formation, carbon and nitrogen transport, and possibly act as antioxidants.[6] The production of cyanogenic glycosides is an evolutionarily conserved function, appearing in species as old as ferns and as recent as angiosperms.[6] These compounds are made by around 3,000 species; in screens they are found in about 11% of cultivated plants but only 5% of plants overall—humans seem to have selected for them.[6]

Examples include amygdalin and prunasin which are made by the bitter almond tree; other species that produce cyanogenic glycosides are sorghum (from which dhurrin, the first cyanogenic glycoside to be identified, was first isolated), barley, flax, white clover, and cassava, which produces linamarin and lotaustralin.[6]

Amygdalin and a synthetic derivative, laetrile, were investigated as potential drugs to treat cancer and were heavily promoted as alternative medicine; they are ineffective and dangerous.[7]

Some butterfly species, such as the Julia butterfly and Parnassius smintheus, have evolved to use the cyanogenic glycosides found in their host plants as a form of protection against predators through their unpalatability.[8][9]

Flavonoid glycosides

Here, the aglycone is a flavonoid. Examples of this large group of glycosides include:

- Hesperidin (aglycone: Hesperetin, glycone: Rutinose)

- Naringin (aglycone: Naringenin, glycone: Rutinose)

- Rutin (aglycone: Quercetin, glycone: Rutinose)

- Quercitrin (aglycone: Quercetin, glycone: Rhamnose)

Among the important effects of flavonoids are their antioxidant effect. They are also known to decrease capillary fragility.

Phenolic glycosides

Here, the aglycone is a simple phenolic structure. An example is arbutin found in the Common Bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi. It has a urinary antiseptic effect.

Saponins

These compounds give a permanent froth when shaken with water. They also cause hemolysis of red blood cells. Saponin glycosides are found in liquorice. Their medicinal value is due to their expectorant, and corticoid and anti-inflammatory effects. Steroid saponins, for example, in Dioscorea wild yam the sapogenin diosgenin—in form of its glycoside dioscin—is an important starting material for production of semi-synthetic glucocorticoids and other steroid hormones such as progesterone. The ginsenosides are triterpene glycosides and Ginseng saponins from Panax Ginseng C. A. Meyer, (Chinese ginseng) and Panax quinquefolius (American Ginseng). In general, the use of the term saponin in organic chemistry is discouraged, because many plant constituents can produce foam, and many triterpene-glycosides are amphipolar under certain conditions, acting as a surfactant. More modern uses of saponins in biotechnology are as adjuvants in vaccines: Quil A and its derivative QS-21, isolated from the bark of Quillaja saponaria Molina, to stimulate both the Th1 immune response and the production of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) against exogenous antigens make them ideal for use in subunit vaccines and vaccines directed against intracellular pathogens as well as for therapeutic cancer vaccines but with the aforementioned side-effect of hemolysis.[10] Saponins are also natural ruminal antiprotozoal agents that are potential to improve ruminal microbial fermentation reducing ammonia concentrations and methane production in ruminant animals.[11]

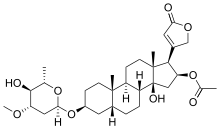

Steroidal glycosides or cardiac glycosides

Here the aglycone part is a steroidal nucleus. These glycosides are found in the plant genera Digitalis, Scilla, and Strophanthus. They are used in the treatment of heart diseases, e.g., congestive heart failure (historically as now recognised does not improve survivability; other agents are now preferred) and arrhythmia.

Steviol glycosides

These sweet glycosides found in the stevia plant Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni have 40-300 times the sweetness of sucrose. The two primary glycosides, stevioside and rebaudioside A, are used as natural sweeteners in many countries. These glycosides have steviol as the aglycone part. Glucose or rhamnose-glucose combinations are bound to the ends of the aglycone to form the different compounds.

Iridoid glycosides

These contain an iridoid group; e.g. aucubin, Geniposidic acid, theviridoside, Loganin, Catalpol.

Thioglycosides

As the name implies (q.v. thio-), these compounds contain sulfur. Examples include sinigrin, found in black mustard, and sinalbin, found in white mustard.

See also

References

- Brito-Arias, Marco (2007). Synthesis and Characterization of Glycosides. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-26251-2.

- Nahrstedt, A.; Davis, R.H. (1983). "Occurrence, variation and biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucosides linamarin and lotaustralin in species of the Heliconiini (Insecta: Lepidoptera)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry. 75 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(83)90041-x.

- "Glycosides". IUPAC Gold Book - Glycosides. 2009. doi:10.1351/goldbook.G02661. ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7.

- Lindhorst, T.K. (2007). Essentials of Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31528-4.

- Robiquet; Boutron-Charlard (1830). "Nouvelles expériences sur les amandes amères et sur l'huile volatile qu'elles fournissent". Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 44: 352–382.

- Gleadow, RM; Møller, BL (2014). "Cyanogenic glycosides: synthesis, physiology, and phenotypic plasticity". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 65: 155–85. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040027. PMID 24579992.

- Milazzo, S; Horneber, M (28 April 2015). "Laetrile treatment for cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005476.pub4. PMC 6513327. PMID 25918920.

- Benson, Woodruff W. (1971). "Evidence for the Evolution of Unpalatability Through Kin Selection in the Heliconinae (Lepidoptera)". The American Naturalist. 105 (943): 213–226. doi:10.1086/282719. JSTOR 2459551.

- Doyle, Amanda. "The roles of temperature and host plant interactions in larval development and population ecology of Parnassius smintheus Doubleday, the Rocky Mountain Apollo butterfly" (PDF). University of Alberta. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Sun, Hong-Xiang; Xie, Yong; Ye, Yi-Ping (2009). "Advances in saponin-based adjuvants". Vaccine. 27 (12): 1787–1796. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.091. PMID 19208455. Archived from the original on 2017-10-08. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- Patra, AK; Saxena, J (2009). "The effect and mode of action of saponins on the microbial populations and fermentation in the rumen and ruminant production". Nutrition Research Reviews. 22 (2): 204–209. doi:10.1017/S0954422409990163. PMID 20003589.

External links

- Definition of glycosides, from the IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, the "Gold Book"

- IUPAC naming rules for glycosides