Naringin

Naringin is a flavanone-7-O-glycoside between the flavanone naringenin and the disaccharide neohesperidose. The flavonoid naringin occurs naturally in citrus fruits, especially in grapefruit, where naringin is responsible for the fruit's bitter taste. In commercial grapefruit juice production, the enzyme naringinase can be used to remove the bitterness created by naringin. In humans naringin is metabolized to the aglycone naringenin (not bitter) by naringinase present in the gut.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

7-[[2-O-(6-Deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy]-2,3-dihydro-5-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | |

| Other names

Naringin Naringoside 4',5,7-Trihydroxyflavanone-7-rhamnoglucoside Naringenin 7-O-neohesperidoside | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.502 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H32O14 | |

| Molar mass | 580.54 g/mol |

| Melting point | 166 °C (331 °F; 439 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

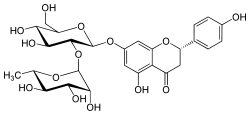

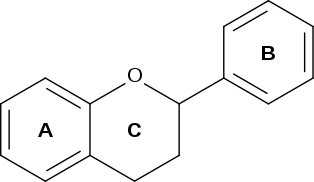

Structure

Naringin belongs to the flavonoid family. Flavonoids consist of 15 carbon atoms in 3 rings, 2 of which must be benzene rings connected by a 3 carbon chain. Naringin contains the basic flavonoid structure along with one rhamnose and one glucose unit attached to its aglycone portion, called naringenin, at the 7-carbon position. The steric hindrance provided by the two sugar units makes naringin less potent than its aglycone counterpart, naringenin.[1]

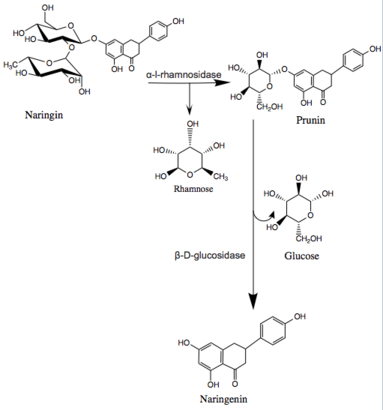

Metabolism

In humans, naringinase is found in the liver and rapidly metabolizes naringin into naringenin. This happens in two steps- first, naringin is hydrolyzed by α-L-rhamnosidase activity of naringinase to rhamnose and prunin. The prunin formed is then hydrolyzed by β-d-glucosidase activity of naringinase into naringenin and glucose.[2] Naringinase is an enzyme that has a wide occurrence in nature and can be found in plants, yeasts, and fungi. It is commercially attractive due to its debittering properties.[2]

Toxicity

The typical concentration of naringin in grapefruit juice is around 400 mg/l.[3] The reported LD50 of naringin in rodents in 2000 mg/kg.[4]

Naringin inhibits some drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP3A4 and CYP1A2, which may result in drug-drug interactions.[5] Ingestion of naringin and related flavonoids can also affect the intestinal absorption of certain drugs, leading to either an increase or decrease in circulating drug levels. To avoid interference with drug absorption and metabolism, the consumption of citrus (especially grapefruit) and other juices with medications is advised against.[6]

However, in vitro studies have also shown that naringin in grapefruit is not what causes the inhibitory effects associated with grapefruit juice. Naringin solution when compared to grapefruit solution produced much less inhibition of CYP3A4.[7] Furthermore, bitter orange juice, which contains considerably less naringin content than grapefruit juice, was found to produce the same level of inhibition of CYP3A4 as grapefruit juice. This would suggest than an inhibitor other than naringin, such as furanocoumarin, which is also found in Seville oranges, may be at work.[7] At the same time, naringenin is known to be a more potent inhibitor of CYP3A4/5 than naringin [8] and in vitro studies have been unable to effectively convert naringin into naringenin. This leaves open the possibility that in vivo, naringin converted into naringenin by naringinase is what causes the inhibitory effect on CY3PA4.[7] Due to the contradictory results of the effect of naringin it is hard to tell whether it is naringin itself or other components of grapefruit juice that cause drug-drug interaction and lead to its toxicity.

Uses

Commercial

When naringin is treated with potassium hydroxide or another strong base, and then catalytically hydrogenated, it becomes a naringin dihydrochalcone, a compound roughly 300–1800 times sweeter than sugar at threshold concentrations.[9]

Further reading

References

- Alam, M. Ashraful; Subhan, Nusrat; Rahman, M. Mahbubur; Uddin, Shaikh J.; Reza, Hasan M.; Sarker, Satyajit D. (2014-07-01). "Effect of Citrus Flavonoids, Naringin and Naringenin, on Metabolic Syndrome and Their Mechanisms of Action". Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal. 5 (4): 404–417. doi:10.3945/an.113.005603. ISSN 2156-5376. PMC 4085189. PMID 25022990.

- Ribeiro, Maria H. (2011-06-01). "Naringinases: occurrence, characteristics, and applications". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 90 (6): 1883–1895. doi:10.1007/s00253-011-3176-8. ISSN 0175-7598. PMID 21544655.

- Yusof, Salmah (January 1990). "Naringin content in local citrus fruits". Food Chemistry. 37 (2): 113–121. doi:10.1016/0308-8146(90)90085-I.

- "Naringin:Safety and Acute toxicity". www.mdidea.com. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- Fuhr U, Kummert AL (1995). "The fate of naringin in humans: a key to grapefruit juice-drug interactions?". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 58 (4): 365–373. doi:10.1016/0009-9236(95)90048-9. PMID 7586927.

- "BBC NEWS, Health, Fruit juice 'could affect drugs'". 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- Edwards, D. J.; Bernier, S. M. (1996-01-01). "Naringin and naringenin are not the primary CYP3A inhibitors in grapefruit juice". Life Sciences. 59 (13): 1025–1030. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00417-1. ISSN 0024-3205. PMID 8809221.

- Lundahl, J.; Regårdh, C. G.; Edgar, B.; Johnsson, G. (1997-01-01). "Effects of grapefruit juice ingestion--pharmacokinetics and haemodynamics of intravenously and orally administered felodipine in healthy men". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 52 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1007/s002280050263. ISSN 0031-6970. PMID 9174684.

- Tomasik P, ed. (2004). Chemical and Functional Properties of Food Saccharides. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-84-931486-5. LCCN 2003053186.

External links