Bretzenheim

Bretzenheim is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Bad Kreuznach district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde Langenlonsheim-Stromberg, whose seat is in Langenlonsheim. Bretzenheim is a state-recognized tourism community[2] and a winegrowing centre. It is also one of the district's ten biggest municipalities.[3]

Bretzenheim | |

|---|---|

Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary | |

Coat of arms | |

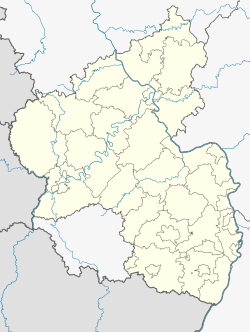

Location of Bretzenheim within Bad Kreuznach district  | |

Bretzenheim  Bretzenheim | |

| Coordinates: 49°52′41″N 7°53′55″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| District | Bad Kreuznach |

| Municipal assoc. | Langenlonsheim-Stromberg |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Thomas Gleichmann (CDU) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.81 km2 (2.24 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 102 m (335 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,593 |

| • Density | 450/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 55559 |

| Dialling codes | 0671 |

| Vehicle registration | KH |

| Website | www.bretzenheim.de |

Geography

Location

Bretzenheim lies on the Nahe, 10 km up from its mouth where it empties into the Rhine at Bingen am Rhein to the north. The municipality lies just north of Bad Kreuznach.

Neighbouring municipalities

Clockwise from the north, Bretzenheim's neighbours are the municipality of Langenlonsheim, the town of Bad Kreuznach and the municipality of Guldental.

History

It was people of the Linear Pottery culture of the New Stone Age who, about 5000 BC, founded the first settlement of any great size at what is now Bretzenheim. A wealth of archaeological finds establish that even in the later epochs of this level of civilization as well as in the time of the Urnfield culture (Bronze Age) and Hallstatt or La Tène times (Iron Age), this place was prized as a good place for a settlement. Later, the Romans came to settle here, bearing witness to whose presence are remnants of several buildings as well as finds of coins and various other things. The Franks might first have appeared here beginning in the 6th century. They introduced a lasting phase of settlement and gave the place its name, meaning “Brezzo’s Home” or “Brizzo’s Home” (although nobody now knows who he was). About the mid 7th century, as historians have assumed, the Archbishop of Cologne acquired Bretzenheim as a royal donation, which he and his successors kept until 1790, although it remained a Free Imperial Domain. The first authoritative documentary mention of Bretzenheim goes back to 1057, when the village was temporarily awarded to the Polish queen Richeza as a “precaria”. Bretzenheim might have taken on its current village structure sometime about the year 1000, to which time the building of the village fortifications with their wall, moats and three gates can be dated. The lordship over the village was exercised by those whom the Archbishop of Cologne enfeoffed, the Electorate of Cologne having been the landholder in the Free Imperial Domain of Bretzenheim until 1789. The fiefholders were at first the Counts Palatine of the Rhine, followed by the Counts of Falkenstein in various lines[4] before Count Alexander II of Velen bought the lordship in 1642. After his descendant Count Alexander IV of Velen died in 1733 without an heir, the Imperial lordship passed in 1734 to Ambrosius Franz von Virmont, who in 1744 likewise died without an heir, whereupon Baron Ignaz Felix von Roll zu Bernau was enfeoffed with Bretzenheim, selling it in 1772 to Count Karl August von Heydeck.[5] This was the beginning of a special historical epoch in Bretzenheim. Count Karl August was Elector Karl Theodor's illegitimate, and still underage, son, and in 1774, he was raised to Imperial Count (Reichsgraf) and in 1789 to Imperial Prince (Reichsfürst), thus raising Bretzenheim itself from Imperial lordship (Reichsherrschaft) to Imperial principality (Reichsfürstentum). Among other things, this gave the Prince the right to mint his own coins, which were called Bretzenheimer Taler. Only six years later, though, in 1795, the principality was beaten within the framework of the Napoleonic Wars and occupied by the French along with the rest of the German lands on the Rhine’s left bank. After the Congress of Vienna, Bretzenheim was grouped into Prussia’s Rhine Province. The apportionment of feudal rights in the village had been laid down in 1456 by a Weistum (cognate with English wisdom, this was a legal pronouncement issued by men learned in law in the Middle Ages and early modern times), which swept all orally handed-down principles aside. While the holders of the village lordship over Bretzenheim and Winzenheim lived at their castles and palaces outside Bretzenheim and had their rights exercised through an Amtmann, Emich Count of Falkenstein actually resided in Bretzenheim from 1589 to 1620, and even had a Schloss built, although this was largely destroyed in the Thirty Years' War. Later, the Count of Velen built a new Schloss wing, and his successor expanded the complex, which nowadays is still mostly preserved in the village centre.[6] Bretzenheim earned itself a measure of infamy after the Second World War. On parts of Bretzenheim’s municipal area from 1945 to 1948 lay a prisoner-of-war camp, the so-called Feld des Jammers (“Field of Misery”), one of the Rheinwiesenlager. A monument at the site nowadays commemorates this camp and its occupants.

"Field of Misery"

Standing today on Bundesstraße 48 (Naheweinstraße), between Bretzenheim and Bad Kreuznach, is a memorial at the site where once lay a notorious prison camp from April 1945 to late 1948, one that was known throughout Germany as the “Field of Misery” (Feld des Jammers). It was not exactly a prisoner-of-war camp, for it had been decided by SHAEF commander in chief Dwight D. Eisenhower that the Wehrmacht soldiers being kept there were to be treated as “Disarmed Enemy Forces” rather than prisoners of war so that they would not be covered by the Geneva Convention, because of the logistical impossibility of feeding millions of surrendered German soldiers at the levels required by the Geneva Convention during the food crisis of 1945. The broad camp, which spread out behind and to both sides of where the memorial now stands, and all the way to the vineyards, had an area of 210 to 220 ha, divided into 24 “cages”. At times, it contained more than 100,000 prisoners. From late April until 10 July 1945, it was under the command of the United States Army, and then from July 1945 to 31 December 1948, having been reduced to only 32 ha, under French occupational authority, first as a camp for war prisoners, and as of October 1945 as a transit camp (Dépôt de transit no.1). Hundreds of thousands of prisoners funnelled through this camp, with some being released to return to their homelands, and others being transported to France for forced labour. A horrifyingly great number of prisoners did not survive the camp, dying of hunger or falling victim to illness. The exact number of deaths cannot be determined. All figures are speculation. Admission today is free, and there are guided tours for those who wish them. Records take the form of documents, reports, journals, drawings, photographs, artefacts, handbills, placards and experiential accounts.[7]

“Field of Misery” memorial; neighbouring village of Bad Kreuznach-Winzenheim in background

“Field of Misery” memorial; neighbouring village of Bad Kreuznach-Winzenheim in background Memorial at the “Field of Misery” to Wilhelm Freiherr (Baron) von Lersner, hailed as, among other things, “Agent of reconciliation between former adversaries”

Memorial at the “Field of Misery” to Wilhelm Freiherr (Baron) von Lersner, hailed as, among other things, “Agent of reconciliation between former adversaries” Memorial to German soldiers who died at the “Field of Misery”

Memorial to German soldiers who died at the “Field of Misery” “Field of Misery” locator map

“Field of Misery” locator map

Jewish history

Bretzenheim had a Jewish community until about 1900. It arose sometime in the 18th century. Even so, as early as the 16th and 17th centuries, there were individual Jews in the village. In 1537, “Jud Salomon” (“Jud” meaning “Jew”) was named, who had leased the former “Falkensteiner Hof” (“Falkenstein Estate”, which stood on a former street called the Nahegasse, now at Große Straße 31, where the narrow sidestreet Winkel meets it), where he is believed to have dealt in wine. Also in the lists of 1550 and 1555/1556 dealing with the Jews who lived in the Electorate of the Palatinate territory, “Salomon von Berzenum” (Berzenum being Bretzenheim) is named. Beginning in 1665, Jews or Jewish families are once again named in the accounts of the Velen comital Amt administration. According to those, there were three Jewish households in Bretzenheim, in 1669 two, in 1675 one, in 1680 two, in 1709 three, in 1720 four and in 1730 seven. The records actually name, among others, a woman called Hanna in Bretzenheim, who after an attack by soldiers on Bretzenheim in October 1675 was robbed. The account of this mentions a loss of a great deal of Krämerware (“general wares”), suggesting that she ran a general store in the village. In 1698, “Jud Abraham” was named and in 1700 “Jud Eysick” (Isaak). In the 18th century, the village Jewish families’ importance grew. In financial houses, in livestock dealing and commodity trading, Jewish inhabitants played an important role. In 1733, the following Jewish family heads were named: Moyses, Davidt, Hertz, Löser, Mayer and Seeligmann. In the years that followed, several Jewish families from other places moved to Bretzenheim. In 1795, nine Jewish families with all together 49 persons were living in the village: Löw Isaac with wife and four children, Majer Löser with wife and three children, Feist Henz with wife and four children, Joseph Abraham with wife, four children and one servant, Majer Moses (widowed) with five children, David with wife, Affron Raphael with wife and five children, Seeligmann Moses with wife and one child. Bretzenheim's Jewish inhabitants then made up 8.33% of the village's total population. In the 19th century, the Jewish population figures developed as follows: in 1808 some 40 Jewish inhabitants; 41 in 1843 (4.44% of all together 922 inhabitants); 22 in 1858 (2.36% of 931); 15 in 1895 (1.64% of 911). In 1808, Bretzenheim's Jewish inhabitants assumed permanent family names. These were Hirsch, Lui, Maier, Mühlstein, Scheier, Stern, Laub and Blum. Already by then, the Jewish families lived in the midst of Christian and other Jewish families right in the village. In 1853, the following Jewish household heads were named: Moses Löb (fruit broker), Abraham Schweig (wine and fruit dealer), Heinrich Schweig's wife (butcher’s trade) and Emrich Schweig (butcher’s trade). In village life, the Jewish families were most thoroughly integrated. They participated as a matter of course in general club life. Between 1848 and 1875, at least five Jewish men, each for six years, were members of the village “fire-quenching team”. When, in 1900, this grew into the Bretzenheim volunteer fire brigade, Moritz Schweig was the first fire chief. In the way of religious establishments, there were a synagogue, a Jewish school, a mikveh and a graveyard. It was in 1774 that a Judenschule (“Jews’ school”, that is to say, synagogue) was first mentioned, which was actually more a prayer room than a full synagogue. It is believed to have been housed somewhere about where numbers 4 and 6 on Große Straße are now. The prayer room was forsaken no later than 1895 when the Jewish community in Bretzenheim joined together with those in Langenlonsheim and Laubenheim. Only one member of Bretzenheim's Jewish community fell in the First World War, Gefreiter Otto Schweig (b. 19 October 1892 in Bretzenheim, d. 24 October 1918). In 1925, only five Jews were still living in the village. As of 1935, there was only one, Bretzenheim-born Hedwig Graf née Schweig, who was married to Heinrich Graf, who was Evangelical, and who managed to survive the Third Reich in the village unmolested. According to the Gedenkbuch – Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945 (“Memorial Book – Victims of the Persecution of the Jews under National Socialist Tyranny”) and Yad Vashem, of all Jews who either were born in Becherbach or lived there for a long time, none died in the time of the Third Reich.[8]

Population development

Bretzenheim's population development since Napoleonic times is shown in the table below. The figures for the years from 1871 to 1987 are drawn from census data:[2]

|

|

Religion

As at 31 August 2013, there are 2,559 full-time residents in Bretzenheim, and of those, 905 are Evangelical (35.365%), 976 are Catholic (38.14%), 2 (0.078%) belong to the Old Catholic Church, 3 (0.117%) belong to the Greek Orthodox Church, 158 (6.174%) belong to other religious groups and 515 (20.125%) either have no religion or will not reveal their religious affiliation.[9]

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 16 council members, who were elected by proportional representation at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.

The municipal election held on 7 June 2009 yielded the following results:[10]

| SPD | CDU | FWL | BBL | Total | |

| 2009 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 16 seats |

| 2004 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 16 seats |

Mayor

Bretzenheim's mayor is Thomas Gleichmann (CDU), and his deputies are Hardy Hollinka (CDU) and Kurt Freis (BBL).[11]

Coat of arms

The municipality's arms might be described thus: Gules a pretzel Or, on a chief Or four lozenges conjoined in fess throughout of the first.

The arms are apparently canting, for the main charge is a pretzel, and Brezel, Bretzel, Brezl and Breze are all words meaning “pretzel” in German, each one somewhat approximating the first two syllables in the municipality's name, Bretzenheim.

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[12]

- Nativity of Mary Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche Mariä Geburt), Kirchstraße 20 – Early Classicist aisleless church, 1789–1791, Building Inspector Faxlunger, Mannheim, mediaeval tower with Baroque spire; at the church a chapel, Classicist building with hip roof, about 1850; missionary cross, marked 1854 and 1857; M. Puricelli tomb, sandstone, 1860; Agnes Utsch tomb, cast-iron grave cross, 1841; fountain trough, cast-iron trough with relief, Rheinböllerhütte (ironworks), latter half of the 19th century; wedding hall bell, marked 1513

- Binger Straße 5 – hook-shaped estate, marked 1761; timber-frame house, plastered, possibly from the 18th century

- Binger Straße 11 – three-sided estate; Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, 17th century, gateway arch marked 1754, barn 1780; border stone, basalt, marked 1677

- Gartenstraße/corner of Mühlenstraße – border stone, possibly from the 18th century

- Große Straße 12 – former Amtshaus (administrative centre of an Amt); Renaissance building, eight-sided stairway tower, marked 1592; border stone from the Archfoundation of Cologne

- Große Straße 14 – Baroque estate complex, 18th century; timber-frame house, plastered, barn, partly timber-frame

- Große Straße 16 – Villa Plettenberg-Puricelli; two-and-a-half-floor plastered building, Renaissance Revival characterized by Late Classicism, marked 1877; further house, clock turret, timber-frame construction with clinker brick, stately side building; fenced-in garden complex with pumphouse, watertower; see Turmstraße (no number) below

- At Große Straße 31 – window embrasure, marked 1606

- Kirchstraße – so-called Altes Schloß (“Old Castle”) of the Counts of Velen; mid 17th century, ruin; girding wall with round tower and gateway arch, quarrystone

- Kirchstraße 2 – former Schloss; after a fire converted into a Baroque palatial residence, 1774, Building Inspector J. Faxlunger, Mannheim; complex grouped about a yard with commercial buildings, Renaissance gateway arch, about 1590, manor house with stairway tower, marked 1595; former dwelling building, about 1600, conversion possibly in 1783

- Kirchstraße 18 – former Catholic rectory; essentially a Late Baroque plastered building, marked 1789, floor added possibly about 1850 in Classicist forms

- Kreuznacher Straße 33 – “Zum grünen Baum” inn; timber-frame building, 17th century, marked 1779

- Kreuzstraße 8 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, marked 1712, gateway complex

- Naheweinstraße 19 – villa of a winegrowing estate, latter half of the 19th century

- Turmstraße (no number) – watertower; lookout tower, eight-sided Gründerzeit brick building, about 1880

- Winkel 4 – estate complex, 18th century, timber-frame house, plastered

- Former hunting lodge, at the Eremitage – Gründerzeit clinker brick building, façade tower, side building, late 19th century

- Eremitage, Eremitager Weg 211 – so-called Antonius-Klause (Klause means “hermit’s cell” in this context); parts of a Romanesque three-naved church hewn out of the cliff; on the cliff wall a mediaeval relief; former hermit dwelling 1759–1761 (see also just below)

- Karlshof – three-sided estate about 1850/1860; Late Classicist main building, incorporated barn wing, wayside cross

- Jewish graveyard, at the municipal limit with Bad Kreuznach, “In der Johanneshohl” (monumental zone) – gravestones from 1863 to 1932 (see also below)

Felseneremitage

Among the wealth of architectural witnesses to Bretzenheim's history, the Felseneremitage (or simply Eremitage, meaning “Hermitage”; Felsen means “cliff”), a place of worship wholly hewn out of a cliff that might even date from antiquity, and that underwent a conversion in early Christian times, is held to be the greatest sightseeing feature, and to be unique north of the Alps. It is believed that its origins lie in a prehistoric place of worship or tribunal site, and that the Romans took over the site in that same function. Its Christian character was supposedly acquired by the 6th or 7th century, even if the first documentary mention of a church there dates from 1043. This and all subsequent churches were partly made of chambers hewn into the cliff, and their remnants can still be seen today. The same is so for the rooms that served as hermits’ cells or a monastic convent, which were wholly hewn out of the stone. The one such dwelling that can still be visited now (90 m²) was for a time home to several hermits or a convent of a cliffside monastery. The last dwellers, between 1716 and 1827, were hermits, who after a long vacancy had once again created here a pilgrimage place known far beyond the borders. The last hermit died in 1827, after 51 “years of service” at the age of 82. The complex can be visited throughout the year without the need of a guided tour.[13][14]

Jewish graveyard

The Jewish graveyard in Bretzenheim might have been laid out as long ago as the 17th century. It was supposedly expanded sometime towards the middle of the 18th century. Other information, however, points to the graveyard's beginnings falling in “Prussian times” (after the Congress of Vienna and before Unification, and thus between 1815 and 1871), especially as the graveyard's area is precisely one Prussian Morgen. The oldest preserved gravestone bears the date 25 November 1863, whereas the newest bears the date 24 September 1932. Still preserved at the graveyard are ten single graves and three double graves. In the time of the Third Reich, the graveyard was not removed: the then mayor, Karl Schmidt, after statements made by Hedwig Graf née Schweig, a Jewish woman married to an Evangelical man and who survived the Nazis in Bretzenheim, opposed the authorities’ demands to obliterate the graveyard. Nevertheless, in 1941/1942, the gravestones were overturned, some of them were stolen, and then in the village they were used as flooring or paving stones. In early 1945, 38 concentration camp prisoners were buried at the graveyard, having died as part of a group of some 500 other prisoners who found themselves doing forced labour in the Bad Kreuznach area towards the end of the war. These prisoners were nationals of various European nations, and some were prisoners of war. They had to do their work, commanded by an SS building brigade, under catastrophic living and dietary conditions. Many died of hunger or illnesses, or were murdered. The people who had been buried at the Bretzenheim Jewish graveyard were exhumed and newly buried at a graveyard of honour at the Bad Kreuznach town cemetery in October 1948, and then in August 1952 at their own graveyard of honour, one for the victims of fascism at the French cemetery. The Bretzenheim Jewish graveyard had to be reconstructed in January 1946 – by former Nazi Party members. Overturned gravestones were once again set upright, trees were trimmed, hedges were removed and the path was made passable once more. In 1951, the graveyard was transferred to the Jewish worship community for the districts of Kreuznach and Birkenfeld. In 1959, the makeshift fence that had been standing at the graveyard was replaced with a trelliswork fence and a closeable gate was installed. The graveyard's area is, according to different sources, 2 186 or 2 255 m², the latter being one Prussian Morgen. The graveyard lies at the municipal limit between Bretzenheim and Bad Kreuznach in the zone known as “Johanneshohl” (in the rural cadastral area called “Auf dem Galgen”).[15]

Economy and infrastructure

Education

Bretzenheim has at its disposal a daycare centre, which is certified as a Bewegungskindergarten (one that emphasizes physical activity as a paedagogical tool), with four groups, among them a “nest group” for children under three years old. There is also a primary school with more than 100 pupils.[16]

Winegrowing

Bretzenheim belongs to the “Nahetal” winegrowing area, itself part of the Nahe wine region. Active in the village are 11 winegrowing operations, and the area of planted vineyards is 112 ha. Some 64% of the grapes grown are white wine varieties (as of 2007). In 1979, there were still 36 winegrowing operations, although the vineyard area was only 94 ha.[17]

Established businesses

Daily needs are ensured by three grocery markets, one clothing discounter, one hairdresser, one florist's shop, two bakeries with cafés, eleven winemakers, one hotel with a restaurant, two inns, many bed and breakfast rooms and flats, four medical practices and one veterinary clinic.[18]

Media

Located in Bretzenheim is Germany's first Pfarrradio (“parish radio station”): Studio Nahe is run by the Catholic parish of Bretzenheim and broadcasts church services and beginning at 10:00 on Saturday a local programme. Domradio Köln (“Cathedral Radio Cologne”) is the standby programme when Studio Nahe has no programme of its own to broadcast. The transmitter lies beneath the churchtower at Nativity of Mary Parish Church and sends its programme on 87.9 MHz with an output of 160 W (vertically polarized), reaching from Bad Kreuznach as far as Bingen am Rhein.

Transport

At Bretzenheim's disposal is a very favourable transport infrastructure with its railway station on the Regionalbahn line serving Bingen am Rhein, Bad Kreuznach and Kaiserslautern (Nahe Valley Railway), three stops on the RNN regional bus network serving Stromberg and Bad Kreuznach, and the nearby link to the Autobahnen A 61 and A 63. Running through the village is Bundesstraße 48. The district seat of Bad Kreuznach borders directly on Bretzenheim's municipal area and can also be reached easily on the Naheradweg (cycle path) between Bingen and Nahequelle (“Source of the Nahe”) near Selbach in the Saarland. The state capitals of Mainz and Wiesbaden, too, as well as Frankfurt Airport and Frankfurt-Hahn Airport can be quickly reached by the good Autobahn and highway links.[19]

References

- "Bevölkerungsstand 2018 - Gemeindeebene". Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz (in German). 2019.

- Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz – Regionaldaten

- General information Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- cf. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-09-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Günther Ebersold: Karl August Reichsfürst von Bretzenheim. Die politische Biographie eines Unpolitischen. BoD, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3833413506

- History Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- “Field of Misery” Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Geschichte der Synagoge Jewish history

- Religion

- Der Landeswahlleiter Rheinland-Pfalz: Kommunalwahl 2009, Stadt- und Gemeinderatswahlen

- Bretzenheim’s council Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Directory of Cultural Monuments in Bad Kreuznach district

- Eremitage Archived September 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Eremitage Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Jewish graveyard

- Education Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz - Infothek

- Established businesses Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Transport Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bretzenheim. |

- Municipality’s official webpage (in German)

- Video portrait of Bretzenheim an der Nahe (in German)

- Brief portrait of Bretzenheim at SWR Fernsehen (in German)