Brazil–Uruguay relations

Brazil–Uruguay relations encompass many complex relations over the span of three centuries, beginning in 1680 with the establishment of the Colónia do Sacramento, to the present day, between the Federative Republic of Brazil and the Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Brazil and Uruguay are neighbouring countries in South America, and share close political, economic and cultural ties. The singularity of the bilateral relationship between the two countries originates from a strong historical connection – marked by important events, such as the establishment of the Colónia do Sacramento in 1680, the invasion of the Banda Oriental by Brazil in 1815 and the subsequent creation of the Província Cisplatina, and Uruguay's independence from Brazil in 1828.[1] The bilateral relationship was further defined by the Uruguayan Civil War (1839–1851) and the Paraguayan War (1864–1870).

| |

Brazil |

Uruguay |

|---|---|

Relations during the late-19th to late-20th centuries were overshadowed by domestic politics and resulted in a period of distancing between the two countries. The signing of the Treaty of Asunción in 1991 initiated a period of closer political, economical and cultural ties. Today, the Brazilian government defines Uruguay as a strategic ally and places the bilateral relationship as a foreign policy priority.[2] This is met with reciprocity by Montevideo.[2] Uruguay has supported the Brazilian bid for a permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council.[2]

History

Colonization

The Spanish arrived in the territory of present-day Uruguay in 1516, but the indigenous people's fierce resistance to conquest, combined with the absence of gold and silver, limited settlement in the region during the 16th and 17th centuries. Uruguay became a zone of contention between the Spanish and the Portuguese empires. In 1603 the Spanish began to introduce cattle, which became a source of wealth in the region. The first permanent settlement on the territory of present-day Uruguay was founded by the Spanish in 1624 at Soriano on the Río Negro. In 1669–71, the Portuguese built a fort at the banks of the Río de la Plata. Founded in 1680 by Portugal as Colónia do Sacramento, the colony was later disputed by the Spanish who settled on the opposite bank of the river at Buenos Aires. The colony was conquered by José de Garro in 1680, but returned to Portugal the next year. It was conquered again by the Spanish in March 1705 after a siege of five months, but was eventually given back to Portugal in the Treaty of Utrecht. Spain would try to regain the colony during the Spanish–Portuguese War of 1735. It kept changing hands from crown to crown due to treaties such as the Treaty of Madrid in 1750 and the Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1777, until it remained with the Spanish.

Annexation and independence

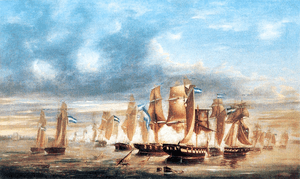

In 1811, José Gervasio Artigas, who became Uruguay's national hero, launched a successful revolt against Spain, defeating Spanish forces on May 18 in the Battle of Las Piedras. He then liberated Montevideo from the centralizing control of Buenos Aires, and in 1815 declared the Liga Federal. In August 1816, forces from Brazil invaded the Banda Oriental (present-day Uruguay) with the intention of destroying the Liga Federal. The Brazilian forces, thanks to their numerical and material superiority, occupied Montevideo on January 20, 1817, and after struggling for three years in the countryside, defeated Artigas in the Battle of Tacuarembó.

In 1821, the Banda Oriental, was annexed by Brazil under the name of Província Cisplatina. In response, the Thirty-Three Orientals, led by Juan Antonio Lavalleja, declared independence from Brazil on August 25, 1825, supported by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (present-day Argentina). This led to the 500-day Cisplatine War. Neither side gained the upper hand, and in 1828 the Treaty of Montevideo, fostered by the British Empire, gave birth to Uruguay as an independent state.

Uruguayan civil war

The political scene in Uruguay following its independence from Brazil became split between two parties, the conservative Blancos and the liberal Colorados. The Colorados were led by Fructuoso Rivera and represented the business interests of Montevideo; the Blancos were headed by Manuel Oribe, who looked after the agricultural interests of the countryside and promoted protectionism.

In 1838, the Kingdom of France started a naval blockade over the port of Buenos Aires, in support of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation, who had declared the War of the Confederation over the Argentine Confederation. Unable to deploy land troops, France sought allied forces to fight Juan Manuel de Rosas - the governor of the Argentine Confederation, on their behalf. For this purpose they helped Fructuoso Rivera to topple the Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe, who was staying in good terms with Rosas.[3] Oribe was exiled to Buenos Aires and Rivera assumed power in October 1838. Rosas did not recognize Rivera as a legitimate president, and sought to restore Oribe in power. Rivera and Juan Lavalle prepared troops to attack Buenos Aires. Both British and French troops intervened, initiating the Uruguayan Civil War, or Guerra Grande (Great War).

Manuel Oribe was eventually defeated in 1851, leaving the Colorados in full control of the country. Brazil followed up by intervening in Uruguay in May 1851, supporting the Colorados with financial and naval forces. In February 1852, Rosas resigned, and the pro-Colorado forces lifted the siege of Montevideo.[4] Uruguay rewarded Brazil's financial and military support by signing five treaties in 1851 that provided for perpetual alliance between the two countries. Montevideo confirmed Brazil's right to intervene in Uruguay's internal affairs. The treaties also allowed joint navigation on the Uruguay River and its tributaries, and tax exempted cattle and salted meat exports. The treaties also acknowledged Uruguay's debt to Brazil for its aid against the Blancos, and Brazil's commitment for granting an additional loan. In addition, Uruguay renounced its territorial claims north of the Quaraí River, thereby reducing its area to about 176,000 square kilometers, and recognized Brazil's exclusive right of navigation in the Lagoa Mirim and the Jaguarão River, the natural border between the countries.[4]

Paraguayan War

In 1855, new conflict broke out between the parties. It reached its high point during the Paraguayan War.[5] In 1863, the Colorado general Venancio Flores organized an armed uprising against the Blanco president, Bernardo Prudencio Berro. Flores won backing from Brazil and, this time, from Argentina, who supplied him with troops and weapons, while Berro made an alliance with the Paraguayan leader Francisco Solano López. When Berro's government was overthrown in 1864 with Brazilian help, López used it as a pretext to declare war on Uruguay. The result was the Paraguayan War, a five-year conflict in which Uruguayan, Brazilian and Argentinian armies fought Paraguay, and which Flores finally won, but only at the price of the loss of 95% of his own troops. Flores did not enjoy his Pyrrhic victory for long. In 1868, he was murdered on the same day as his rival Berro.

Both parties were weary of the chaos. In 1870, they came to an agreement to define spheres of influence: the Colorados would control Montevideo and the coastal region, the Blancos would rule the hinterland with its agricultural estates. In addition, the Blancos were paid half a million dollars to compensate them for the loss of their stake in Montevideo. But the caudillo mentality was difficult to erase from Uruguay and political feuding continued culminating in the Revolution of the Lances (Revolución de las Lanzas) (1870–1872), and later with the uprising of Aparicio Saravia, who was fatally injured at the Battle of Masoller (1904).

Recent years

On 30 July 2010, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil and Uruguays' José Mujica signed cooperation agreements on defence, science, technology, energy, river transportation and fishing with the hope of accelerating political and economic integration between these two neighbouring countries.[6]

Cross-border region

The Brazil–Uruguay border extends 1,068 kilometres (664 mi).[7] The close geographic proximity of some Brazilian and Uruguayan cities or urban centers have led them to be called "twin cities".[8] These cities usually share close demographic, economic, and political bonds. The following are twin cities:[8]

| Population | Border type | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuí | 6,564 | land (avenue) | Chuy | 10,401 |

| Jaguarão | 58,855 | river (international bridge) | Río Branco | 13,456 |

| Aceguá | 5,538 | land (avenue) | Aceguá | 4,578 |

| Santana do Livramento | 97,488 | land (plaza) | Rivera | 64,326 |

| Quaraí | 25,044 | river (international bridge) | Artigas | 41,687 |

| Barra do Quaraí | 4,578 | river (international bridge) | Bella Unión | 13,187 |

Border disputes

A longstanding border dispute involving territory in the vicinity of Masoller exists between Uruguay and Brazil, although this has not harmed close diplomatic and economic relations between the two countries. The disputed area is called Rincón de Artigas (Portuguese: Rincão de Artigas, Location -31.00, -55.95), and the dispute arises from the fact that the treaty that delimited the Brazil-Uruguay border in 1861 determined that the border in that area would be a creek called Arroyo de la Invernada (Portuguese: Arroio da Invernada), but the two countries disagree on which actual stream is the so-named one.[9]

Another disputed territory is Brazilian Island at the confluence of the Quaraí River and the Uruguay River.[10]

Trade and investment

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $1 billion | $1.2 billion | $1.6 billion | $1.4 billion | $1.5 billion | $2 billion | ||

| $0.6 billion | $0.8 billion | $1 billion | $1.2 billion | $1.6 billion | $1.7 billion | ||

| Total trade | $1.6 billion | $2 billion | $2.6 billion | $2.6 billion | $3.1 billion | $3.7 billion | |

| Note: All values are in U.S. dollars. Source: SECEX.[11] | |||||||

Resident diplomatic missions

|

|

See also

References

- Relaciones Bilaterales Embaixada do Brasil em Montevideo. Retrieved on 2011-12-24. (in Spanish).

- Atos assinados por ocasião da visita da Presidenta Dilma Rousseff ao Uruguai - Montevidéu, 30 de maio de 2011 Archived April 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Ministério das Relações Exteriores. Retrieved on 2011-12-24. (in Portuguese).

- Garibaldi in Uruguay: A Reputation Reconsidered.

- The Great War, 1843–52. Library of Congress. Retrieved on 2011-12-25.

- José M. Olivero Oreechia, "Chronology of the Uruguayan Army in the War of the Triple Alliance," Military Collector and Historian, Winter 2007, Vol. 59 Issue 4, pp 269-276

- Brazil and Uruguay step closer to integration American Express Travel. Retrieved on 2011-12-24.

- Fronteira Brasil/Uruguai Laboratório Nacional de Computação Científica. Retrieved on 2011-12-24. (in Portuguese).

- Relações Brasil-Uruguai: A Nova Agenda para a Cooperação e o Desenvolvimento Fronteiriço Archived May 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Aveiro, Thais Mere. University of Brasília. Retrieved on 2011-12-24. (in Portuguese).

- Griswold, Clark (2013-03-10). "The current territorial disputes of Brazil". Férias do Clark (personal blog) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2014-06-07.

- Borders and Limits of Brazil: Ilha Brasileira Archived March 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Wilson R.M. Krukoski, LNCC. Retrieved on 2009-06-23. (in Portuguese).

- Intercâmbio Comercial - Uruguai SECEX. Retrieved on 2011-12-24. (in Portuguese).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of Brazil and Uruguay. |

- Embassy of Brazil in Montevideo Official website

- Embassy of Uruguay in Brasília Official website