Braveheart

Braveheart is a 1995 American epic historical fiction war film directed and co-produced by Mel Gibson, who portrays William Wallace, a late-13th-century Scottish warrior. The film depicts the life of Wallace leading the Scots in the First War of Scottish Independence against King Edward I of England. The film also stars Sophie Marceau, Patrick McGoohan and Catherine McCormack. The story is inspired by Blind Harry's 15th century epic poem The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace and was adapted for the screen by Randall Wallace.

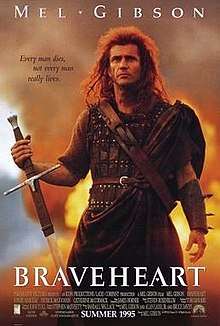

| Braveheart | |

|---|---|

North American theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mel Gibson |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Randall Wallace |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Horner |

| Cinematography | John Toll |

| Edited by | Steven Rosenblum |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (North America) 20th Century Fox (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 178 minutes |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $65–70 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $213.2 million[2] |

Development on the film initially started at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer when producer Alan Ladd Jr. picked up the project from Wallace, but when MGM was going through new management, Ladd left the studio and took the project with him. Despite initially declining, Gibson eventually decided to direct the film, as well as star as Wallace. The film was filmed in Scotland and Ireland from June to October 1994 with a budget around $65–70 million.[4] Braveheart, which was produced by Gibson's Icon Productions and The Ladd Company, was distributed by Paramount Pictures in North America and by 20th Century Fox internationally.

Released on May 24, 1995, Braveheart received generally positive reviews from critics, who praised the performances, directing, production values, battle sequences, and musical score, but criticized its historical inaccuracies, especially regarding Wallace's title, love interests, and attire.[5] The film grossed $75.6 million in the US and grossed $210.4 million worldwide. At the 68th Academy Awards, the film was nominated for ten Academy Awards and won five: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Makeup, and Best Sound Effects Editing. A spin-off sequel, Robert the Bruce, was released in 2019, with Angus Macfadyen reprising his role.

Plot

In 1280, King Edward "Longshanks" invades and conquers Scotland following the death of Alexander III of Scotland, who left no heir to the throne. Young William Wallace witnesses Longshanks' treachery, survives the deaths of his father and brother, and is taken abroad on a pilgrimage throughout Europe by his paternal uncle Argyle, where he is educated. Years later, in 1297, Longshanks grants his noblemen land and privileges in Scotland, including Prima Nocte. Meanwhile, a grown Wallace returns to Scotland and falls in love with his childhood friend Murron MacClannough, and the two marry in secret. Wallace rescues Murron from being raped by English soldiers, but as she fights off their second attempt, Murron is captured and publicly executed. In retribution, Wallace leads his clan to slaughter the English garrison in his hometown and send the occupying garrison at Lanark back to England.

Longshanks orders his son Prince Edward to stop Wallace by any means necessary. Alongside his friend Hamish, Wallace rebels against the English, and as his legend spreads, hundreds of Scots from the surrounding clans join him. Wallace leads his army to victory at the Battle of Stirling and then destroys the city of York, killing Longshanks' nephew and sending his severed head to the king. Wallace seeks the assistance of Robert the Bruce, the son of nobleman Robert the Elder and a contender for the Scottish crown. Robert is dominated by his father, who wishes to secure the throne for his son by submitting to the English. Worried by the threat of the rebellion, Longshanks sends his son's wife Isabella of France to try to negotiate with Wallace as a distraction for the landing of another invasion force in Scotland.

After meeting him in person, Isabella becomes enamored of Wallace. She warns him of the coming invasion, and Wallace implores the Scottish nobility to take immediate action to counter the threat and take back the country, asking Robert the Bruce to lead. In 1298, leading the English army himself, Longshanks confronts the Scots at Falkirk. There, noblemen Mornay and Lochlan turn their backs on Wallace after being bribed by the king, resulting in the death of Hamish's father, Campbell. Wallace is then further betrayed when he discovers Robert the Bruce was fighting alongside Longshanks; after the battle, after seeing the damage he helped do to his countrymen, the Bruce reprimands his father and vows not to be on the wrong side again.

Wallace kills Lochlan and Mornay for their betrayal, and wages a guerrilla war against the English for the next seven years, assisted by Isabella, with whom he eventually has an affair. In 1305, Robert sets up a meeting with Wallace in Edinburgh, but Robert's father has conspired with other nobles to capture and hand over Wallace to the English. Learning of his treachery, Robert disowns and banishes his father. Isabella exacts revenge on the now terminally ill Longshanks by telling him that his bloodline will be destroyed upon his death as she is now pregnant with Wallace's child.

In London, Wallace is brought before an English magistrate, tried for high treason, and condemned to public torture and beheading. Even whilst being hanged, drawn and quartered, Wallace refuses to submit to the king. The watching crowd, deeply moved by the Scotsman's valor, begin crying for mercy. The magistrate offers him one final chance, asking him only to utter the word, "Mercy", and be granted a quick death. Wallace instead shouts, "Freedom!", and his cry rings through the square, Longshanks hearing it just before dying. The judge orders Wallace's death. While being decapitated, Wallace sees a vision of Murron in the crowd, smiling at him.

In 1314, Robert, now Scotland's king, leads a Scottish army before a ceremonial line of English troops on the fields of Bannockburn, where he is to formally accept English rule. As he begins to ride toward the English, he stops and invokes Wallace's memory, imploring his men to fight with him as they did with Wallace. Hamish throws Wallace's sword point-down in front of the English army, and he and the Scots chant Wallace's name. Robert then leads his army into battle against the stunned English, winning the Scots their freedom.

Cast

- Mel Gibson as William Wallace

- Jamie Robinson as Young William Wallace

- Sophie Marceau as Princess Isabella of France

- Angus Macfadyen as Robert the Bruce

- Patrick McGoohan as King Edward "Longshanks"

- Catherine McCormack as Murron MacClannough

- Mhairi Calvey as Young Murron

- Brendan Gleeson as Hamish

- Andrew Weir as Young Hamish

- Peter Hanly as Prince Edward

- James Cosmo as Campbell

- David O'Hara as Stephen of Ireland

- Ian Bannen as Bruce's father

- Seán McGinley as MacClannough

- Brian Cox as Argyle Wallace

- Sean Lawlor as Malcolm Wallace

- Sandy Nelson as John Wallace

- Stephen Billington as Phillip

- John Kavanagh as Craig

- Alun Armstrong as Mornay

- John Murtagh as Lochlan

- Tommy Flanagan as Morrison

- Donal Gibson as Stewart

- Jeanne Marine as Nicolette

- Michael Byrne as Smythe

- Malcolm Tierney as Magistrate

- Bernard Horsfall as Balliol

- Peter Mullan as Veteran

- Gerard McSorley as Cheltham (inspired by Hugh de Cressingham)

- Richard Leaf as Governor of York

- Mark Lees as Old Crippled Scotsman

- Tam White as MacGregor

- Jimmy Chisholm as Faudron

- David Gant as the Royal Magistrate

Production

Producer Alan Ladd Jr. initially had the project at MGM-Pathé Communications when he picked up the script from Wallace.[6] When MGM was going through new management in 1993, Ladd left the studio and took some of its top properties, including Braveheart.[7] Gibson came across the script and even though he liked it, he initially passed on it. However, the thought of it kept coming back to him and he ultimately decided to take on the project.[6] Gibson was initially interested in directing only and considered Brad Pitt in the role of William Wallace, but Gibson reluctantly agreed to play Wallace as well.[3]

Gibson and his production company, Icon Productions, had difficulty raising enough money for the film. Warner Bros. was willing to fund the project on the condition that Gibson sign for another Lethal Weapon sequel, which he refused. Gibson eventually gained enough financing for the film, with Paramount Pictures financing a third of the budget in exchange for North American distribution rights to the film, and 20th Century Fox putting up two thirds of the budget in exchange for international distribution rights.[8][3]

Principal photography on the film began on June 6, 1994.[4] While the crew spent three weeks shooting on location in Scotland, the major battle scenes were shot in Ireland using members of the Irish Army Reserve as extras. To lower costs, Gibson had the same extras, up to 1,600 in some scenes, portray both armies. The reservists had been given permission to grow beards and swapped their military uniforms for medieval garb.[9] Principal photography ended on October 28, 1994.[4] The film was shot in the anamorphic format with Panavision C- and E-Series lenses.[10]

Gibson had to tone down the film's battle scenes to avoid an NC-17 rating from the MPAA; the final version was rated R for "brutal medieval warfare".[11] Gibson and editor Steven Rosenblum initially had a film at 195 minutes, but Sheryl Lansing, who was the head of Paramount at the time, requested Gibson and Rosenblum to cut the film down to 177 minutes.[12] According to Gibson in a 2016 interview with Collider, there is a four-hour version of the film and would be interested in reassembling it if both Paramount and Fox are interested.[13]

Soundtrack

The score was composed and conducted by James Horner and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. It is Horner's second of three collaborations with Mel Gibson as director. The score has gone on to be one of the most commercially successful soundtracks of all time. It received considerable acclaim from film critics and audiences and was nominated for a number of awards, including the Academy Award, Saturn Award, BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe Award.

Release and reception

Box office

On its opening weekend, Braveheart grossed $9,938,276 in the United States and $75.6 million in its box office run in the U.S. and Canada.[2] Worldwide, the film grossed $210,409,945 and was the thirteenth-highest-grossing film of 1995.[2]

Critical response

Braveheart earned positive reviews; critics praised Gibson's direction and performance as Wallace, the performances of its cast, and its screenplay, production values, Horner's score, and the battle sequences. The depiction of the Battle of Stirling Bridge was listed by CNN as one of the best battles in cinema history.[14] However, it was also criticized for its depiction of history. On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 78%, with an average score of 7.29/10, based on 81 reviews. The site's consensus states "Distractingly violent and historically dodgy, Mel Gibson's Braveheart justifies its epic length by delivering enough sweeping action, drama, and romance to match its ambition."[15] On Metacritic the film has a score of 68 out of 100 based on 20 critic reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[16] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade A- on scale of A to F.[17]

.jpg)

Caryn James of The New York Times praised the film, calling it "one of the most spectacular entertainments in years." Roger Ebert gave the film 3.5 stars out of four, calling it "An action epic with the spirit of the Hollywood swordplay classics and the grungy ferocity of The Road Warrior."[18] In a positive review, Gene Siskel wrote that "in addition to staging battle scenes well, Gibson also manages to recreate the filth and mood of 700 years ago."[19] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone felt that "though the film dawdles a bit with the shimmery, dappled love stuff involving Wallace with a Scottish peasant and a French princess, the action will pin you to your seat."[20]

Not all reviews were positive, Richard Schickel of TIME magazine argued that "everybody knows that a non-blubbering clause is standard in all movie stars' contracts. Too bad there isn't one banning self-indulgence when they direct."[21] Peter Stack of San Francisco Chronicle felt "at times the film seems an obsessive ode to Mel Gibson machismo."[22] In a 2005 poll by British film magazine Empire, Braveheart was No. 1 on their list of "The Top 10 Worst Pictures to Win Best Picture Oscar".[23] Empire readers had previously voted Braveheart the best film of 1995.[24]

Effect on tourism

The European premiere was on September 3, 1995, in Stirling.[25]

In 1996, the year after the film was released, the annual three-day "Braveheart Conference" at Stirling Castle attracted fans of Braveheart, increasing the conference's attendance to 167,000 from 66,000 in the previous year.[26] In the following year, research on visitors to the Stirling area indicated that 55% of the visitors had seen Braveheart. Of visitors from outside Scotland, 15% of those who saw Braveheart said it influenced their decision to visit the country. Of all visitors who saw Braveheart, 39% said the film influenced in part their decision to visit Stirling, and 19% said the film was one of the main reasons for their visit.[27] In the same year, a tourism report said that the "Braveheart effect" earned Scotland £7 million to £15 million in tourist revenue, and the report led to various national organizations encouraging international film productions to take place in Scotland.[28]

The film generated huge interest in Scotland and in Scottish history, not only around the world, but also in Scotland itself. At a Braveheart Convention in 1997, held in Stirling the day after the Scottish Devolution vote and attended by 200 delegates from around the world, Braveheart author Randall Wallace, Seoras Wallace of the Wallace Clan, Scottish historian David Ross and Bláithín FitzGerald from Ireland gave lectures on various aspects of the film. Several of the actors also attended including James Robinson (Young William), Andrew Weir (Young Hamish), Julie Austin (the young bride) and Mhairi Calvey (Young Murron).

Awards and honors

Braveheart was nominated for many awards during the 1995 Oscar season, though it was not viewed by many as a major contender such as Apollo 13, Il Postino: The Postman, Leaving Las Vegas, Sense and Sensibility, and The Usual Suspects. It wasn't until after the film won the Golden Globe Award for Best Director at the 53rd Golden Globe Awards that it was viewed as a serious Oscar contender. When the nominations were announced for the 68th Academy Awards, Braveheart received ten Academy Award nominations, and a month later, won five including Best Picture, Best Director for Gibson, Best Cinematography, Best Sound Effects Editing, and Best Makeup.[29] Braveheart became the ninth film to win Best Picture with no acting nominations and is one of only three films to win Best Picture without being nominated for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture, the other being The Shape of Water in 2017 and followed by Green Book the following year.[30][31][32] The film also won the Writer's Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay.[33] In 2010, the Independent Film & Television Alliance selected the film as one of the 30 Most Significant Independent Films of the last 30 years[34]

- American Film Institute lists

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies – Nominated[35]

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills – No. 91

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- William Wallace – Nominated Hero[36]

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes:

- "They may take away our lives, but they'll never take our freedom!" – Nominated[37]

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[38]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – No. 62

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated[39]

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Epic Film[40]

Cultural effects

Lin Anderson, author of Braveheart: From Hollywood To Holyrood, credits the film with playing a significant role in affecting the Scottish political landscape in the mid-to-late 1990s.[41]

Wallace Monument

In 1997, a 12-foot (3.7 m), 13-tonne (13-long-ton; 14-short-ton) sandstone statue depicting Mel Gibson as William Wallace in Braveheart was placed in the car park of the Wallace Monument near Stirling, Scotland. The statue, which was the work of Tom Church, a monumental mason from Brechin,[42] included the word 'Braveheart' on Wallace's shield. The installation became the cause of much controversy; one local resident stated that it was wrong to "desecrate the main memorial to Wallace with a lump of crap".[43] In 1998, someone wielding a hammer vandalized the statue's face. After repairs were made, the statue was encased in a cage every night to prevent further vandalism. This only incited more calls for the statue to be removed, as it then appeared that the Gibson/Wallace figure was imprisoned. The statue was described as "among the most loathed pieces of public art in Scotland".[44] In 2008, the statue was returned to its sculptor to make room for a new visitor centre being built at the foot of the Wallace Monument.[45]

Historical inaccuracy

Randall Wallace, who wrote the screenplay, has acknowledged Blind Harry's 15th-century epic poem The Acts and Deeds of Sir William Wallace, Knight of Elderslie as a major inspiration for the film.[46] In defending his script, Randall Wallace has said, "Is Blind Harry true? I don't know. I know that it spoke to my heart and that's what matters to me, that it spoke to my heart."[46] Blind Harry's poem is not regarded as historically accurate, and although some incidents in the film that are not historically accurate are taken from Blind Harry (e.g. the hanging of Scottish nobles at the start),[47] there are large parts that are based neither on history nor Blind Harry (e.g. Wallace's affair with Princess Isabella).[5]

Elizabeth Ewan describes Braveheart as a film that "almost totally sacrifices historical accuracy for epic adventure".[48] The "brave heart" refers in Scottish history to that of Robert the Bruce, and an attribution by William Edmondstoune Aytoun, in his poem Heart of Bruce, to Sir James the Good Douglas: "Pass thee first, thou dauntless heart, As thou wert wont of yore!", prior to Douglas' demise at the Battle of Teba in Andalusia.[49] It has been described as one of the most historically inaccurate modern films.[5]

Sharon Krossa noted that the film contains numerous historical inaccuracies, beginning with the wearing of belted plaid by Wallace and his men. In that period "no Scots [...] wore belted plaids (let alone kilts of any kind)." Moreover, when Highlanders finally did begin wearing the belted plaid, it was not "in the rather bizarre style depicted in the film". She compares the inaccuracy to "a film about Colonial America showing the colonial men wearing 20th century business suits, but with the jackets worn back-to-front instead of the right way around."[50] In a previous essay about the film, she wrote, "The events aren't accurate, the dates aren't accurate, the characters aren't accurate, the names aren't accurate, the clothes aren't accurate—in short, just about nothing is accurate."[51] The belted plaid (feileadh mór léine) was not introduced until the 16th century.[52] Peter Traquair has referred to Wallace's "farcical representation as a wild and hairy highlander painted with woad (1,000 years too late) running amok in a tartan kilt (500 years too early)."[53] In fact, Wallace was a lowlander; thus, the mountains and glens of his home as depicted in the film are also inaccurate.

Irish historian Seán Duffy remarked "the battle of Stirling Bridge could have done with a bridge."[54]

In 2009, the film was second on a list of "most historically inaccurate movies" in The Times.[5] In the humorous non-fictional historiography An Utterly Impartial History of Britain (2007), author John O'Farrell claims that Braveheart could not have been more historically inaccurate, even if a Plasticine dog had been inserted in the film and the title changed to "William Wallace and Gromit".[55]

In the DVD audio commentary of Braveheart, Mel Gibson acknowledges many of the historical inaccuracies but defends his choices as director, noting that the way events were portrayed in the film was much more "cinematically compelling" than the historical fact or conventional mythos.[5]

Jus primae noctis

Edward Longshanks, King of England, is shown invoking Jus primae noctis, allowing the lord of a medieval estate to take the virginity of his serfs' maiden daughters on their wedding nights. Critical medieval scholarship regards this supposed right as a myth: "the simple reason why we are dealing with a myth here rests in the surprising fact that practically all writers who make any such claims have never been able or willing to cite any trustworthy source, if they have any."[56][57]

Occupation and independence

The film suggests Scotland had been under English occupation for some time, at least during Wallace's childhood, and in the run-up to the Battle of Falkirk Wallace says to the younger Bruce, "[W]e'll have what none of us have ever had before, a country of our own." In fact, Scotland had been invaded by England only the year before Wallace's rebellion; prior to the death of King Alexander III it had been a fully separate kingdom.[58] After Alexander III death in 1286 his granddaughter Margaret, Maid of Norway, succeeded to the throne of Scotland until her death in 1290 in Orkney.

At one point, Wallace's uncle refers to a piper as "playing outlawed tunes on outlawed pipes." Not only were bagpipes not outlawed at the time, they likely had not yet been introduced to Scotland. Further, the widely-held belief that bagpipes were banned by the Act of Proscription 1746 (400 years later), is erroneous. Bagpipes were never specifically outlawed in Scotland.

Portrayal of William Wallace

As John Shelton Lawrence and Robert Jewett writes, "Because [William] Wallace is one of Scotland's most important national heroes and because he lived in the very distant past, much that is believed about him is probably the stuff of legend. But there is a factual strand that historians agree to", summarized from Scots scholar Matt Ewart:

Wallace was born into the gentry of Scotland; his father lived until he was 18, his mother until his 24th year; he killed the sheriff of Lanark when he was 27, apparently after the murder of his wife; he led a group of commoners against the English in a very successful battle at Stirling in 1297, temporarily receiving appointment as guardian; Wallace's reputation as a military leader was ruined in the same year of 1297, leading to his resignation as guardian; he spent several years of exile in France before being captured by the English at Glasgow, this resulting in his trial for treason and his cruel execution.[59]

A. E. Christa Canitz writes about the historical William Wallace further: "[He] was a younger son of the Scottish gentry, usually accompanied by his own chaplain, well-educated, and eventually, having been appointed Guardian of the Kingdom of Scotland, engaged in diplomatic correspondence with the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck and Hamburg". She finds that in Braveheart, "any hint of his descent from the lowland gentry (i.e., the lesser nobility) is erased, and he is presented as an economically and politically marginalized Highlander and 'a farmer'—as one with the common peasant, and with a strong spiritual connection to the land which he is destined to liberate."[60]

Colin McArthur writes that Braveheart "constructs Wallace as a kind of modern, nationalist guerrilla leader in a period half a millennium before the appearance of nationalism on the historical stage as a concept under which disparate classes and interests might be mobilised within a nation state." Writing about Braveheart's "omissions of verified historical facts", McArthur notes that Wallace made "overtures to Edward I seeking less severe treatment after his defeat at Falkirk", as well as "the well-documented fact of Wallace's having resorted to conscription and his willingness to hang those who refused to serve."[61] Canitz posits that depicting "such lack of class solidarity" as the conscriptions and related hangings "would contaminate the movie's image of Wallace as the morally irreproachable primus inter pares among his peasant fighters."[60]

Portrayal of Isabella of France

Isabella of France is shown having an affair with Wallace after the Battle of Falkirk. She later tells Edward I she is pregnant, implying that her son, Edward III, was a product of the affair. In reality, Isabella was around three years old and living in France at the time of the Battle of Falkirk, was not married to Edward II until he was already king, and Edward III was born seven years after Wallace died.[62][5] Her menacing suggestion, to a dying Longshanks, that she would overthrow and destroy Edward II is based in fact. However, it was only in 1326, over 20 years after Wallace's death, that Isabella, her son, and her lover Roger Mortimer would invade England to depose - and later murder - Edward II.

Portrayal of Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce did change sides between the Scots loyalists and the English more than once in the earlier stages of the Wars of Scottish Independence, but he probably did not fight on the English side at the Battle of Falkirk (although this claim does appear in a few medieval sources).[63] Later, the Battle of Bannockburn was not a spontaneous battle; he had already been fighting a guerrilla campaign against the English for eight years.[64] His title before becoming king was Earl of Carrick, not Earl of Bruce.[65][66] In particular, while the film's name refers to protagonist William Wallace, the nickname "Braveheart" has been posthumously attributed to the Bruce, whose heart was brought to a Crusade in Spain by Sir James Douglas and thrown into a battle against the Moors.[67] Bruce's heart was then returned to Scotland and interred at Melrose Abbey.[68][69] Bruce's father, the real Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale, is portrayed as an infirm leper, a fact actually transmuted from Bruce himself, though only much later in his reign. In the film, Bruce's father - and presumably the ruling lord - betrays Wallace to his son's disgust, acknowledging it as the price of his crown, although in real life Wallace was betrayed by the nobleman John de Menteith and delivered to the English. Although the film exaggerates Bruce's role in Wallace's downfall, there is some uncertainty to what extent these dialogues should be taken literally. No other character interacts with "father" in the film, and the sequence may as well be taken as a portrayal of Bruce's internal conflict between pragmatic schemer with a desire to unite his country and impulsive patriot, a conflict explored throughout Bruce's story arc. In the end, his growing power secures him the ability to finally expel the English, in which he acknowledges his debt to Wallace's efforts. In reality, the rebellion of 1297-98 was a stepping stone in the larger string of conflicts, and there is no reason to suggest Bruce took a more anti-English stance as result of its failure.

Portrayal of Longshanks and Prince Edward

The actual Edward I was ruthless and temperamental, but the film exaggerates his negative aspects for effect. Edward enjoyed poetry and harp music, was a devoted and loving husband to his wife Eleanor of Castile, and as a religious man, he gave generously to charity. The film's scene where he scoffs cynically at Isabella for distributing gold to the poor after Wallace refuses it as a bribe would have been unlikely. Also, Edward died on campaign two years after Wallace's execution, not in bed at his home.[70]

The depiction of the future Edward II as an effeminate homosexual drew accusations of homophobia against Gibson.

We cut a scene out, unfortunately ... where you really got to know that character [Edward II] and to understand his plight and his pain ... But it just stopped the film in the first act so much that you thought, 'When's this story going to start?'[71]

Gibson defended his depiction of Prince Edward as weak and ineffectual, saying:

I'm just trying to respond to history. You can cite other examples—Alexander the Great, for example, who conquered the entire world, was also a homosexual. But this story isn't about Alexander the Great. It's about Edward II.[72]

In response to Longshanks' murder of the Prince's male lover Phillip, Gibson replied: "The fact that King Edward throws this character out a window has nothing to do with him being gay ... He's terrible to his son, to everybody."[73] Gibson asserted that the reason Longshanks kills his son's lover is because the king is a "psychopath".[74] Gibson expressed bewilderment that some filmgoers would laugh at this murder.[75]

Wallace's military campaign

"MacGregors from the next glen" joining Wallace shortly after the action at Lanark is dubious, since it is questionable whether Clan Gregor existed at that stage, and when they did emerge their traditional home was Glen Orchy, some distance from Lanark.[76]

Wallace did win an important victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, but the version in Braveheart is highly inaccurate, as it was filmed without a bridge (and without Andrew Moray, joint commander of the Scots army, who was fatally injured in the battle). Later, Wallace did carry out a large-scale raid into the north of England, but he did not get as far south as York, nor did he kill Longshanks' nephew[77] (however, this was not as wide of the mark as Blind Harry, who has Wallace making it as far south as St. Albans, and only refraining from attacking London after the English queen came out to meet him).[47] Edward's nephew John of Brittany did take part in the Wars of Scottish Independence, but he was not killed, dying of natural causes.[78]

The "Irish conscripts" at the Battle of Falkirk are also unhistorical; there were no Irish troops at Falkirk (although many of the English army were actually Welsh) [79] and it is anachronistic to refer to conscripts in the Middle Ages (although there were feudal levies).

The two-handed long swords used by Gibson in the film were not in wide use in the period. A one-handed sword and shield would have been more accurate.[80]

Accusations of Anglophobia

Sections of the English media accused the film of harboring Anglophobia. The Economist called it "xenophobic",[81] and John Sutherland writing in The Guardian stated that: "Braveheart gave full rein to a toxic Anglophobia".[82][83][84]

In The Times, Colin McArthur said "the political effects are truly pernicious. It's a xenophobic film."[83] Ian Burrell of The Independent has noted, "The Braveheart phenomenon, a Hollywood-inspired rise in Scottish nationalism, has been linked to a rise in anti-English prejudice".[85]

Home media

Braveheart was released on DVD on August 29, 2000.[86] It was released on Blu-ray as part of the Paramount Sapphire Series on September 1, 2009.[87] It was released on 4K UHD Blu-ray as part of the 4K upgrade of the Paramount Sapphire Series on May 15, 2018.[87]

Sequel

On February 9, 2018, a sequel titled Robert the Bruce was announced. The film will lead directly on from Braveheart and follow the widow Moira, portrayed by Anna Hutchison, and her family (portrayed by Gabriel Bateman and Talitha Bateman), who save Robert the Bruce, with Angus Macfadyen reprising his role from Braveheart. The cast will also include Jared Harris, Patrick Fugit, Zach McGowan, Emma Kenney, Diarmaid Murtagh, Seoras Wallace, Shane Coffey, Kevin McNally, and Melora Walters. Richard Gray will direct the film, with Macfadyen and Eric Belgau writing the script. Helmer Gray, Macfadyen, Hutchison, Kim Barnard, Nick Farnell, Cameron Nuggent, and Andrew Curry will produce the film.[88]

See also

- Outlaw King; although not a sequel, it depicts events that occurred immediately after the events in Braveheart

References

- "Braveheart (1995)". British Film Institute. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- "Braveheart (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- THR Staff (April 18, 2017). "Mel Gibson Once Threw an Ashtray Through a Wall During 'Braveheart' Budget Talks". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- "Braveheart (1995) - Misc Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- White, Caroline. "The 10 most historically inaccurate movies". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- gaspare88 (February 7, 2018), Making Of Braveheart Behind The Scenes Documentary, retrieved October 26, 2018

- Nollen, Scott Allen (January 1, 1999). Robin Hood: A Cinematic History of the English Outlaw and His Scottish Counterparts. McFarland. ISBN 9780786406432.

- Michael Fleming (July 25, 2005). "Mel tongue-ties studios". Daily Variety.

- "Braveheart 10th Chance To Boost Tourism In Trim". Meath Chronicle. August 28, 2003. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- Chris Probst (June 1, 1996). "Cinematic Transcendence". American Cinematographer. Los Angeles, California, United States: American Society of Cinematographers. 77 (6): 76. ISSN 0002-7928.

- Classification and Rating Administration; Motion Picture Association of America. "Reasons for Movie Ratings (CARA)". Archived from the original on December 11, 2010.

- "Mel Gibson reveals secrets from behind the scenes of Braveheart". www.news.com.au. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Levine, Nick (October 26, 2016). "Mel Gibson has a whole hour of unseen 'Braveheart' footage for an extended cut". NME. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- "The best – and worst – movie battle scenes". CNN. March 30, 2007. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- "Braveheart". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- "Braveheart". Metacritic. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "BRAVEHEART (1995) A-". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger. "Braveheart movie review & film summary (1995)". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Siskel, Gene. "`CRUMB' DIGS DEEP AS THE OSCARS COME UP EMPTY". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- Travers, Peter (May 24, 1995). "Braveheart". Rolling Stone.

- Schickel, Richard (May 29, 1995). "CINEMA: ANOTHER HIGHLAND FLING". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "FILM REVIEW -- Macho Mel Beats His Chest in Bloody `Braveheart'". SFGate. May 24, 1995. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "Mel Gibson's "Braveheart" Voted Worst Oscar Winner". hollywood.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013.

- "Empire Award Past Winners - 1996". Empireonline.com. Bauer Consumer Media. 2003. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- "Scotland a nation again for a night". The Herald. Glasgow. September 4, 1995. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- Zumkhawala-Cook, Richard (2008). Scotland as We Know It: Representations of National Identity in Literature, Film and Popular Culture. McFarland. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-7864-4031-3.

- MacLellan, Rory; Smith, Ronnie (1998). Tourism in Scotland. Cengage Learning EMEA. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-86152-089-0.

- Martin-Jones, David (2009). Scotland: Global Cinema – Genres, Modes, and Identities. Edinburgh University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7486-3391-3.

- "The 68th Academy Awards (1996) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- "'BRAVEHEART' CONQUERS\Gibson's epic wins Best Picture\Sarandon, Cage take acting honors. - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- "Oscars Avoids "Envelopegate" Repeat as 'The Shape of Water' Takes Home Best Picture Prize". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- America, Good Morning. "Oscars 2019: 'Green Book' wins best picture". Good Morning America. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- WELKOS, ROBERT W. (March 19, 1996). "WGA Members Prize 'Sensibility' and 'Braveheart'". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- "UPDATE: How "Toxic" Is IFTA's Best Indies?". Deadline. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (PDF). Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains Nominees Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- "HollywoodBowlBallot" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- "Movies_Ballot_06" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10 Ballot" (PDF). Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Boztas, Senay (July 31, 2005). "Wallace movie 'helped Scots get devolution' – [Sunday Herald]". Braveheart.info. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- "Wallace statue back at home of sculptor". The Courier. October 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- Hal G. P. Colebatch (August 8, 2006). "The American Spectator". Spectator.org. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- Kevin Hurley (September 19, 2004). "They may take our lives but they won't take Freedom". Scotland on Sunday. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- "Wallace statue back with sculptor". BBC News. October 16, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- Anderson, Lin (2005). Braveheart: From Hollywood to Holyrood. Luath Press Ltd. p. 27.

- Unmapping the Territory: Blind Hary's Wallace, Felicity Riddy's chapter in Edward Cowan's The Wallace Book (2007, ISBN 978-0-85976-652-4)

- Ewan, Elizabeth (October 1995). "Braveheart". American Historical Review. 100 (4): 1219–21. doi:10.2307/2168219.

- "Lays of the Scottish Cavaliers and Other Poems / Aytoun, W. E. (William Edmondstoune), 1813–1865". Infomotions.com. February 4, 2004. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Krossa, Sharon L. (October 2, 2008). "Braveheart Errors: An Illustration of Scale". Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- Krossa, Sharon L. (October 31, 2001). "Regarding the Film Braveheart". Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- "A History of Scottish Kilts | Authentic Ireland Travel". Authenticireland.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Traquair, Peter (1998). Freedom's Sword. HarperCollins. p. 62

- "History Ireland". History Ireland. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- O'Farrell, John (2007). An Utterly Impartial History of Britain. New York City: Doubleday. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-385-61198-5.

- Classen, Albrecht (2007). The medieval chastity belt: a myth-making process. London: Macmillan. p. 151. ISBN 9781403975584. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013.

- "Urban legends website". Snopes.com. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Traquair p. 15

- Shelton Lawrence, John; Jewett, Robert (2002). The Myth of the American Superhero. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 163.

- Canitz, A.E. Christa (2005). "'Historians ... Will Say I Am a liar': The Ideology of False Truth Claims in Mel Gibson's Braveheart and Luc Besson's The Messenger". In Utz, Richard J.; Swan, Jesse G. (eds.). Studies in Medievalism XIII: Postmodern Medievalisms. Suffolk, United Kingdom: D.S. Brewer. pp. 127–142. ISBN 978-1-84384-012-1.

- McArthur, Colin (1998). "Braveheart and the Scottish Aesthetic Dementia". In Barta, Tony (ed.). Screening the Past: Film and the Representation of History. Praeger. pp. 167–187. ISBN 978-0-275-95402-4.

- Ewan, Elizabeth (October 1995). "Braveheart". The American Historical Review. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 100 (4): 1219–21. doi:10.2307/2168219. ISSN 0002-8762. OCLC 01830326.

- Penman, Michael Robert the Bruce: King of the Scots pp. 58-59

- Traquair pp. 128-176

- Traquair p. 58

- "BraveHeart – the 10 historical inaccuracies you need to know before watching the movie". December 5, 2011.

- "Sorry, William Wallace – Robert the Bruce Was the Actual Braveheart (And Was Way More Violent Too)".

- "The Heart of Robert the Bruce". June 2016.

- "The Buried Heart of Scottish Hero Robert the Bruce".

- Traquair p. 147

- Della Cava, Marco R. (May 24, 1995). "Gibson has faith in family and freedom". USA Today.

- Stein, Ruth (May 21, 1995). "Mel Gibson Dons Kilt and Directs". San Francisco Chronicle.

- "Gay Alliance has Gibson's 'Braveheart' in its sights", Daily News, May 11, 1995, archived from the original on June 4, 2011, retrieved February 13, 2010

- Matt Zoller Seitz (May 25, 1995). "Icon: Mel Gibson talks about Braveheart, movie stardom, and media treachery". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- "Braveheart: The 10 historical inaccuracies you need to know before watching the movie".

- Way, George & Squire, Romily (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. pp. 220–221.

- Traquair pp. 77-79

- Jones, Michael (2004). "Brittany, John of, earl of Richmond (1266?–1334)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53083.

- Traquair pp. 81-84

- Matt, Easton. "Two-handed swords in Ironclad, Braveheart, Robin Hood & Kingdom of Heaven". YouTube. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Economist.com". Economist.com. May 18, 2006. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- "John Sutherland". The Guardian. London. August 11, 2003. Archived from the original on August 20, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- "Braveheart battle cry is now but a whisper". Times Online. London. July 24, 2005. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- Colin, McArthur (2003). Brigadoon, Braveheart and the Scots: Distortions of Scotland in Hollywood Cinema. I. B. Tauris. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-86064-927-1. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013.

- Burrell, Ian (February 8, 1999). "Most race attack victims `are white': The English Exiles – News". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- Various (August 29, 2000), Braveheart, Warner Bros., retrieved May 15, 2018

- "Braveheart DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Busch, Anita (February 9, 2018). "Angus Macfadyen-Led Action Drama 'Robert The Bruce' Drafts Jared Harris, Patrick Fugit & Others". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Braveheart |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Braveheart. |