The French Connection (film)

The French Connection is a 1971 American action-thriller film[6] directed by William Friedkin. The screenplay, written by Ernest Tidyman, is based on Robin Moore's 1969 non-fiction book The French Connection. It tells the story of New York Police Department detectives Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle and Buddy "Cloudy" Russo, whose real-life counterparts were Narcotics Detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, in pursuit of wealthy French heroin smuggler Alain Charnier. The film stars Gene Hackman as Popeye, Roy Scheider as Cloudy, and Fernando Rey as Charnier. Tony Lo Bianco and Marcel Bozzuffi also star.

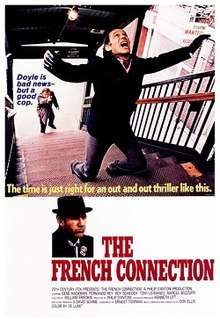

| The French Connection | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William Friedkin |

| Produced by | Philip D'Antoni |

| Screenplay by | Ernest Tidyman |

| Based on | The French Connection by Robin Moore |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Don Ellis |

| Cinematography | Owen Roizman |

| Edited by | Gerald B. Greenberg |

Production company | Philip D'Antoni Productions |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $1.8 million[3] |

| Box office | |

At the 44th Academy Awards, it won the Oscars for Best Picture, Best Actor (Hackman), Best Director (Friedkin), Best Film Editing, and Best Adapted Screenplay (Tidyman). It was nominated for Best Supporting Actor (Scheider), Best Cinematography, and Best Sound Mixing. Tidyman also received a Golden Globe Award nomination, a Writers Guild of America Award, and an Edgar Award for his screenplay. A sequel, French Connection II, followed in 1975 with Gene Hackman and Fernando Rey reprising their roles.

The American Film Institute included the film in its list of the best American films in 1998 and again in 2007. In 2005, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

In Marseille, an undercover police detective follows Alain Charnier, who runs the world's largest heroin-smuggling syndicate. The policeman is assassinated by Charnier's hitman, Pierre Nicoli. Charnier plans to smuggle $32 million worth of heroin into the United States by hiding it in the car of his unsuspecting friend, television personality Henri Devereaux, who is traveling to New York City by ship.

In New York City, detectives Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle and Buddy "Cloudy" Russo go out for drinks at the Copacabana. Popeye notices Salvatore "Sal" Boca and his young wife, Angie, entertaining mobsters involved in narcotics. They tail the couple and establish a link between the Bocas and lawyer Joel Weinstock, who is part of the narcotics underworld.

Popeye learns from an informant that a massive shipment of heroin will arrive in the next two weeks. The detectives convince their supervisor to wiretap the Bocas' phones. Popeye and Cloudy are joined by federal agents Mulderig and Klein.

Devereaux's vehicle arrives in New York City. Boca is impatient to make the purchase—reflecting Charnier's desire to return to France as soon as possible—while Weinstock, with more experience in smuggling, urges patience, knowing Boca's phone is tapped and that they are being investigated.

Charnier realizes he is being observed. He "makes" Popeye and escapes on a departing subway shuttle. To avoid being tailed, he has Boca meet him in Washington D.C., where Boca asks for a delay to avoid the police. Charnier, however, wants to conclude the deal quickly. On the flight back to New York City, Nicoli offers to kill Popeye, but Charnier objects, knowing that Popeye would be replaced by another policeman. Nicoli insists, however, saying they will be back in France before a replacement is assigned.

Soon after, Nicoli attempts to shoot Popeye but misses. Popeye chases Nicoli, who boards an elevated train. Popeye commandeers a car and gives chase. Realizing he is being pursued, Nicoli works his way forward through the carriages, shoots a policeman who tries to intervene and hijacks the motorman at gunpoint, forcing him to drive straight through the next station, also shooting the train conductor. The motorman passes out and they are just about to slam into a stationary train when an emergency trackside brake engages, hurling the assassin against a glass window. Popeye arrives to see the killer descending from the platform. When the killer sees Popeye, he turns to run but is shot dead by Popeye.

After a lengthy stakeout, Popeye impounds Devereaux's Lincoln Continental. He and his team take it apart searching for the drugs, but come up empty-handed. Cloudy notes that the vehicle's shipping weight is 120 pounds over its listed manufacturer's weight. They remove the rocker panels and discover the heroin concealed therein. The police restore the car to its original condition and return it to Devereaux, who delivers the Lincoln Continental to Charnier.

Charnier drives to an old factory on Wards Island to meet Weinstock and deliver the drugs. After Charnier has the rocker panels removed, Weinstock's chemist tests one of the bags and confirms its quality. Charnier removes the drugs and hides the money, concealing it beneath the rocker panels of another car purchased at an auction of junk cars, which he will take back to France. Charnier and Sal drive off in the Lincoln, but hit a roadblock with a large contingent of police led by Popeye. The police chase the Lincoln back to the factory, where Boca is killed during a shootout while most of the other criminals surrender.

Charnier escapes into the warehouse with Popeye and Cloudy in pursuit. Popeye sees a shadowy figure in the distance and opens fire a split-second after shouting a warning, killing Mulderig. Undaunted, Popeye tells Cloudy that he will get Charnier. After reloading his gun, Popeye runs into another room and a single gunshot is heard.

Title cards note that Weinstock was indicted but his case dismissed for "lack of proper evidence"; Angie Boca received a suspended sentence for an unspecified misdemeanor; Lou Boca received a reduced sentence; Devereaux served four years in a federal penitentiary for conspiracy; and Charnier was never caught. Popeye and Cloudy were transferred out of the narcotics division and reassigned.

Cast

- Gene Hackman as Det. Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle

- Fernando Rey as Alain "Frog One" Charnier

- Roy Scheider as Det. Buddy "Cloudy" Russo

- Tony Lo Bianco as Salvatore "Sal" Boca

- Marcel Bozzuffi as Pierre Nicoli

- Frédéric de Pasquale as Henri Devereaux

- Bill Hickman as Bill Mulderig

- Ann Rebbot as Mrs. Marie Charnier

- Harold Gary as Joel Weinstock

- Arlene Farber as Angie Boca

- Eddie Egan as Walt Simonson

- André Ernotte as La Valle

- Sonny Grosso as Clyde Klein

- Alan Weeks as Pusher

Production

The film was originally set up at National General Pictures but they later dropped it and Richard Zanuck and David Brown offered to make it at Fox with a production budget of $1.5 million.[1] The film came in $300,000 over budget at a total cost of $1.8 million.[3]

In an audio commentary track recorded by Friedkin for the Collector's Edition DVD release of the film, Friedkin notes that the film's documentary-like realism was the direct result of the influence of having seen Z, a French film. The film was among the earliest to show the World Trade Center: the completed North Tower and the partially completed South Tower are seen in the background of the scenes at the shipyard following Devereaux's arrival in New York.

Friedkin credits his decision to direct the movie to a discussion with film director Howard Hawks, whose daughter was living with Friedkin at the time. Friedkin asked Hawks what he thought of his movies, to which Hawks bluntly replied that they were "lousy." Instead Hawks recommended that he "Make a good chase. Make one better than anyone's done."[7]

Casting

Though the cast ultimately proved to be one of the film's greatest strengths, Friedkin had problems with casting choices from the start. He was strongly opposed to the choice of Hackman for the lead, and actually first considered Paul Newman (out of the budget range), then Jackie Gleason, Peter Boyle and a New York columnist, Jimmy Breslin, who had never acted before.[Note 1] However, Gleason, at that time, was considered box-office poison by the studio after his film Gigot had flopped several years before, Boyle declined the role after disapproving of the violent theme of the film, and Breslin refused to get behind the wheel of a car, which was required of Popeye's character for an integral car chase scene. Steve McQueen was also considered, but he did not want to do another police film after Bullitt and, as with Newman, his fee would have exceeded the movie's budget. Tough guy Charles Bronson was also considered for the role. Friedkin almost settled for Rod Taylor (who had actively pursued the role, according to Hackman), another choice the studio approved, before he went with Hackman.

The casting of Fernando Rey as the main French heroin smuggler, Alain Charnier (irreverently referred to throughout the film as "Frog One"), resulted from mistaken identity. Friedkin had seen Luis Buñuel's 1967 French film Belle de Jour and had been impressed by the performance of Francisco Rabal, who had a small role in the film. However, Friedkin did not know his name, and remembered only that he was a Spanish actor. He asked his casting director to find the actor, and the casting director instead contacted Rey, a Spanish actor who had appeared in several other films directed by Buñuel. After Rabal was finally reached, they discovered he spoke neither French nor English, and Rey was kept in the film.[Note 1] Ironically, after screening the film's final cut, Rey's French was deemed unacceptable by the filmmakers. They decided to dub his French while preserving his English dialogue.

Comparison to actual people

The plot centers on drug smuggling in the 1960s and early 1970s, when most of the heroin illegally imported into the East Coast came to the United States through France (see French Connection). In addition to the two main protagonists, several of the fictional characters depicted in the film also have real-life counterparts. The Alain Charnier character is based upon Jean Jehan who was arrested later in Paris for drug trafficking, though he was not extradited since France does not extradite its citizens.[8] Sal Boca is based on Pasquale "Patsy" Fuca, and his brother Anthony. Angie Boca is based on Patsy's wife Barbara, who later wrote a book with Robin Moore detailing her life with Patsy. The Fucas and their uncle were part of a heroin dealing crew that worked with some of the New York City crime families.[9] Henri Devereaux, who takes the fall for importing the Lincoln to New York City, is based on Jacques Angelvin, a television actor arrested and sentenced to three to six years in a federal penitentiary for his role, serving about four before returning to France and turning to real estate.[10] The Joel Weinstock character is, according to the director's commentary, a composite of several similar drug dealers.[11]

Car chase

The film is often cited as containing one of the greatest car chase sequences in movie history.[12] The chase involves Popeye commandeering a civilian's car (a 1971 Pontiac LeMans) and then frantically chasing an elevated train, on which a hitman is trying to escape. The scene was filmed in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn roughly running under the BMT West End Line (currently the D train, then the B train) which runs on an elevated track above Stillwell Avenue, 86th Street and New Utrecht Avenue in Brooklyn, with the chase ending just north of the 62nd Street station. At that point, the train hits a train stop, but is going too fast to stop in time and collides with the train ahead of it, which has just left the station.[Note 2]

The most famous shot of the chase is made from a front bumper mount and shows a low-angle point of view shot of the streets racing by. Director of photography Owen Roizman wrote in American Cinematographer magazine in 1972 that the camera was undercranked to 18 frames per second to enhance the sense of speed. Roizman's contention is borne out when you see a car at a red light whose exhaust pipe is pumping smoke at an accelerated rate. Other shots involved stunt drivers who were supposed to barely miss hitting the speeding car, but due to errors in timing, accidental collisions occurred and were left in the final film.[13] Friedkin said that he used Santana's cover of Fleetwood Mac's song "Black Magic Woman" during editing to help shape the chase sequence; though the song does not appear in the film, "it [the chase scene] did have a sort of pre-ordained rhythm to it that came from the music."[14]

The scene concludes with Doyle confronting Nicoli the hitman at the stairs leading to the subway and shooting him as he tries to run back up them.[Note 3] Many of the police officers acting as advisers for the film objected to the scene on the grounds that shooting a suspect in the back was simply murder, not self-defense, but director Friedkin stood by it, stating that he was "secure in my conviction that that's exactly what Eddie Egan (the model for Doyle) would have done and Eddie was on the set while all of this was being shot."[15][16]

Filming locations

The French Connection was filmed in the following locations:[17][18][19][20]

- 50th Street and First Avenue, New York City (where Doyle waits outside the restaurant)

- 82nd Street and Fifth Avenue (near the Metropolitan Museum of Art), New York City, (Weinstock's apartment)

- 86th Street, Brooklyn, New York City (the chase scene)

- 91 Wyckoff Avenue, Bushwick, Brooklyn (Sal and Angie's Cafe)

- 940 2nd Avenue, New York City (where Charnier and Nicoli buy fruit and Popeye is watching)

- 177 Mulberry Street near Broome street, Little Italy, New York City (where Sal makes a drop)

- Avenue De L'Amiral Ganteaume, Cassis, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (Charnier's house)

- Château d'If, Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (where Charnier and Nicoli meet Devereaux)

- Chez Fon Fon, Rue Du Vallon Des Auffes, Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (where Charnier dines)

- Columbia Heights, Brooklyn, New York City, New York, USA (where Sal parks the Lincoln)

- Le Copain, 891 First Ave, New York City, New York, USA (where Charnier dines)

- Doral Park Avenue Hotel (now 70 Park Avenue Hotel), 38th Street and Park Avenue, New York City, New York, USA (Devereaux's hotel)

- Dover street near by the Brooklyn Bridge, New York City, New York, (where Sal leaves the Lincoln)

- Forest Avenue, Ridgewood, Queens, New York City, New York,

- Grand Central Station Shuttle, Manhattan, New York City, New York,

- Henry Hudson Parkway Route 9A at Junction 24 (car accident)

- Marlboro Housing Project, Avenues V, W, and X off Stillwell Avenue, Brooklyn, New York, (where Popeye lives)

- Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, France

- Montee Des Accoules, Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, France

- Onderdonk Avenue, Ridgewood, Queens, New York City

- Plage du bestouan, Cassis, Bouches-du-Rhône, France

- Putnam Avenue, Ridgewood, Queens, New York City

- Randalls Island, East River, New York City

- Ratner's Restaurant, 138 Delancey Street, New York City (where Sal and Angie emerge)

- Remsen Street, Brooklyn, New York City (where Charnier and Nicoli watch the car being unloaded)

- Rio Piedras (now demolished), 912 Broadway, Brooklyn, New York City (where the Santa Claus chase starts)

- Rapid Park Garage, East 38th Street near Park Avenue, New York City (where Cloudy follows Sal)

- Ronaldo Maia Flowers, 27 East 67th Street at Madison, New York City (where Charnier gives Popeye the slip)

- The Roosevelt Hotel, 45th Street and Madison Avenue, Manhattan, New York City

- Rue des Moulins off Rue Du Panier, Old Town of Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (where the French policeman with the bread walks)

- La Samaritaine at 2 Quai Du Port, Marseille, Bouches-du-Rhône, France

- South Street at Market Street at the foot of Manhattan Bridge, New York City (where Doyle emerges from a bar)

- Triborough Bridge to Randall's Island toll bridge at the east end of 125th Street, New York City

- Wards Island, New York City (the final shootout)

- Washington, D.C., USA (where Charnier and Sal meet)

- Westbury Hotel, 15 East 69th Street, Manhattan, New York City, New York, (Charnier's hotel)

Reception

Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film 4 out of 4 stars and ranked it as one of the best films of 1971.[21] Roger Greenspun of The New York Times said of the film, "the ads say that the time is just right for an out-and-out thriller like this, and I guess that you are supposed to think that a good old kind of movie has none too soon come around again. But The French Connection ... is in fact a very good new kind of movie, and that in spite of its being composed of such ancient material as cops and crooks, with thrills and chases, and lots of shoot-'em-up."[22] A review in Variety stated, "So many changes have been made in Robin Moore's taut, factual reprise of one of the biggest narcotics hauls in New York police history that only the skeleton remains, but producer Philip D'Antoni and screenwriter Ernest Tidyman have added enough fictional flesh to provide director William Friedkin and his overall topnotch cast with plenty of material, and they make the most of it."[23] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune awarded a full 4 stars out of 4 and raved, "From the moment a street-corner Santa Claus chases a drug pusher thru the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, to the final shootout on deserted Ward's Island, 'The French Connection' is a gutty, flatout thriller, far superior to any caper film of recent vintage."[24] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "every bit as entertaining as 'Bullitt,' a slam-bang, suspenseful, plain-spoken, sardonically funny, furiously paced melodrama. But because it has dropped the romance and starry glamor of Steve McQueen and added a strong sociological concern, 'The French Connection' is even more interesting, thought-provoking and reverberating."[25] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post called the film "an undeniably sensational movie, a fast, tense, explosively vicious little cops-and-robbers enterprise" with "a deliberately nervewracking, runaway quality ... It's a cheap thrill in the same way that a roller coaster ride is a cheap thrill. It seems altogether appropriate that the showiest sequence intercuts between a runaway train and a recklessly speeding car."[26] John Simon in a positive review of The French Connection wrote "Friedkin has used New York locations better than anyone to day," "The performances are all good", and "Owen Roizman's cinematography, grainy and grimy, is a brilliant rendering of urban blight."[27]

Pauline Kael of The New Yorker was generally negative, writing, "It's not what I want not because it fails (it doesn't fail), but because of what it is. It is, I think, what we once feared mass entertainment might become: jolts for jocks. There's nothing in the movie that you enjoy thinking about afterward—nothing especially clever except the timing of the subway-door-and-umbrella sequence. Every other effect of the movie—even the climactic car-versus-runaway-elevated-train chase—is achieved by noise, speed, and brutality."[28] David Pirie of The Monthly Film Bulletin called the film "consistently exciting" and Gene Hackman "extremely convincing as Doyle, trailing his suspects with a shambling determination; but there are times when the film (or at any rate the script) seems to be applauding aspects of his character which are more repulsive than sympathetic. Whereas in The Detective or Bullitt the hero's attention was directed unmistakably towards liberal ends (crooked businessmen, corrupt local officials, etc.) Doyle spends a fair part of his time beating up sullen blacks in alleys and bars. These violent sequences are almost all presented racily and amusingly, stressing Doyle's 'lovable' toughness as he manhandles and arrests petty criminals, usually adding a quip like 'Lock them up and throw away the key.'"[29]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 98% based on 56 reviews, with an average rating of 8.74/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Realistic, fast-paced and uncommonly smart, The French Connection is bolstered by stellar performances by Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider, not to mention William Friedkin's thrilling production."[30]

In 2014, Time Out listed The French Connection as the 31st best action film of all time, according to a poll of several film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors.[31]

The French Connection has been described as a neo-noir film by some authors.[32]

Awards and nominations

The American Film Institute recognizes The French Connection on several of its lists:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies - #70

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) - #93

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Thrills - #8

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains: Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle - #44 Hero

In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed the film as the tenth best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[36]

Home media releases

The film has been issued in a number of home video formats. For a 2009 reissue on Blu-ray, William Friedkin controversially altered the film's color timing to give it a "colder" look.[37] Cinematographer Owen Roizman, who was not consulted about the changes, dismissed the new transfer as "atrocious".[38] On March 18, 2012, a new Blu-ray transfer of the movie was released. This time the color-timing was supervised by both Friedkin and Roizman, and the desaturated and sometimes over-grainy look of the 2009 edition have been corrected.[39][40]

Sequels and adaptations

- French Connection II (1975) is a fictional sequel.

- NBC-TV aired a made-for-TV movie, Popeye Doyle (1986), another fictional sequel starring Ed O'Neill in the title role.

See also

Notes

- Tied with Walter Matthau for Kotch.

- Friedkin recounts his casting opinions in Making the Connection: The Untold Stories (2001). Extra feature on 2001 Five Star Collection edition of DVD release.

- R42 cars 4572 and 4573 were chosen for the film and had no B subway rollsigns because they were normally assigned to the N subway train. Consequently, they operated during the movie with an N displayed. As of July 2009, these cars were withdrawn from service, but are preserved as part of the Transit Museum fleet.

- A still shot from this scene is depicted in the movie poster shown at the top of this Wikipedia page.

References

- The French Connection at the American Film Institute Catalog

- "THE FRENCH CONNECTION (18)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Bart, Peter (August 8, 2011). "'Alien' territory: an economics lesson". Variety. p. 2. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "The French Connection, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, p. 167, ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

- "The French Connection (1971) - William Friedkin". AllMovie.

- McCarthy, Todd. Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood Pg. 625. Grove Press, 2000 ISBN 0-8021-3740-7, ISBN 978-0-8021-3740-1

- "Turner Classic Movies spotlight". TCM. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- Moore, Robin (1969). The French Connection: A True Account of Cops, Narcotics, and International Conspiracy. ISBN 1592280447.

- Bauer, Alain; Soullez, Christophe (2012). La criminologie pour les nuls (Générales First ed.). ISBN 2754031626.

- Film commentary

- "Top 10 car chase movies - MOVIES - MSNBC.com". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- This account of the shooting is described in Making the Connection, supra.

- ""From 'Popeye' Doyle to Puccini: William Friedkin" with Robert Siegel (interview), NPR, 14 Sep 2006". Npr.org. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- Director's commentary on DVD

- "Making the Connection" and "The Poughkeepsie Shuffle", documentaries on The French Connection available on the deluxe DVD.

- "The French Connection film locations". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- "The French Connection". Reel Streets. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- "Locations for The French Connection". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- "The Filming Locations of The French Connection, Then and Now". Scouting NY. 2014-05-21. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1971). "The French Connection Review". Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- Greenspun, Roger (October 8, 1971). "The French Connection (1971)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- "Film Reviews: The French Connection". Variety. October 6, 1971. 16.

- Siskel, Gene (November 8, 1971). "French Connection". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 20.

- Champlin, Charles (November 3, 1971). "High Adventure in 'Connection'". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- Arnold, Gary (November 12, 1971). "'French Connection': Running and Hitting". The Washington Post. C1.

- Simon, John (1982). Reverse Angle: A Decade of American Film. Crown Publishers Inc. p. 57.

- Kael, Pauline (October 30, 1971). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. 115.

- Pirie, David (January 1972). "The French Connection". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 39 (456): 7.

- "The French Connection (1971)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- "The 100 best action movies ever made".

- Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth; eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.). Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5

- Awards for The French Connection on IMDb

- "The 44th Academy Awards (1972) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- "The 20th Annual Golden Globe Awards (1972) Nominees and Winners". goldenglobes.org. Archived from the original on 2010-11-24.

- "The 75 Best Edited Films". Editors Guild Magazine. 1 (3). May 2012.

- Kehr, Dave (February 20, 2009). "Filmmaking at 90 Miles Per Hour". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Jeffrey Wells (February 25, 2009). "Atrocious...Horrifying". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- "The French Connection Gets a New Blu-ray Release, New Master".

- "The French Connection Blu-ray".

Further reading

- Collins, Dave (November 29, 2014). "Man linked to heroin ring in '71 film nabbed again". Associated Press.

- Friedkin, William (April 15, 2003). "Under the Influence: The French Connection". DGA Magazine.

- Friedkin, William (Fall 2006). "Anatomy of a Chase: The French Connection". DGA Magazine.

- Kehr, Dave (February 20, 2009). "Filmmaking at 90 Miles Per Hour: A 2009 retrospective". The New York Times. (subscription required)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The French Connection (film) |