Brahmin

Brahmin (/ˈbrɑːmɪn/; Sanskrit: ब्राह्मण) are a varna (class) in Hinduism. They specialised as priests (purohit, pandit, or pujari), teachers (acharya or guru) and protectors of sacred learning across generations.[1][2]

The traditional occupation of Brahmins was that of priesthood at the Hindu temples or at socio-religious ceremonies and rite of passage rituals such as solemnising a wedding with hymns and prayers.[2][3] Theoretically, the Brahmins were the highest ranking of the four social classes.[4] In practice, Indian texts suggest that Brahmins were agriculturalists, warriors, traders and have held a variety of other occupations in the Indian subcontinent.[3][5][4]

Vedic sources

Purusha Sukta

The earliest inferred reference to "Brahmin" as a possible social class is in the Rigveda, occurs once, and the hymn is called Purusha Sukta.[6] According to this hymn in Mandala 10, Brahmins are described as having emerged from the mouth of Purusha, being that part of the body from which words emerge.[7][8][note 1] This Purusha Sukta varna verse is now generally considered to have been inserted at a later date into the Vedic text, possibly as a charter myth.[9] Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, a professor of Sanskrit and Religious studies, state, "there is no evidence in the Rigveda for an elaborate, much-subdivided and overarching caste system", and "the varna system seems to be embryonic in the Rigveda and, both then and later, a social ideal rather than a social reality".[9]

Shrauta Sutras

Ancient texts describing community-oriented Vedic yajna rituals mention four to five priests: the hotar, the adhvaryu, the udgatar, the Brahmin and sometimes the ritvij.[10][11] The functions associated with the priests were:

- The Hotri recites invocations and litanies drawn from the Rigveda.[12]

- The Adhvaryu is the priest's assistant and is in charge of the physical details of the ritual like measuring the ground, building the altar explained in the Yajurveda. The adhvaryu offers oblations.[12]

- The Udgatri is the chanter of hymns set to melodies and music (sāman) drawn from the Samaveda. The udgatar, like the hotar, chants the introductory, accompanying and benediction hymns.[12]

- The Brahmin recites from the Atharvaveda.[11]

- The Ritvij is the chief operating priest.[11]

According to Kulkarni, the Grhya-sutras state that Yajna, Adhyayana (studying the vedas and teaching), dana pratigraha (accepting and giving gifts) are the "peculiar duties and privileges of brahmins".[13]

Brahmin and renunciation tradition in Hinduism

The term Brahmin in Indian texts has signified someone who is good and virtuous, not just someone of priestly class.[14] Both Buddhist and Brahmanical literature, states Patrick Olivelle, repeatedly define "Brahmin" not in terms of family of birth, but in terms of personal qualities.[14] These virtues and characteristics mirror the values cherished in Hinduism during the Sannyasa stage of life, or the life of renunciation for spiritual pursuits. Brahmins, states Olivelle, were the social class from which most ascetics came.[14]

Dharmasutras and Dharmashastras

The Dharmasutras and Dharmasatras text of Hinduism describe the expectations, duties and role of Brahmins. The rules and duties in these Dharma texts of Hinduism, are primarily directed at Brahmins. The Gautama's Dharmasutra, the oldest of surviving Hindu Dharmasutras, for example, states in verse 9.54–9.55 that a Brahmin should not participate or perform a ritual unless he is invited to do so, but he may attend. Gautama outlines the following rules of conduct for a Brahmin, in Chapters 8 and 9:[15]

A [Brahmin] man who has performed the forty sacramental rites, but lacks eight virtues does not obtain union with or residence in the same world as Brahman. A man who may have performed just some rites, but possesses these eight virtues, on the other hand, does.

—Gautama Dharmasutra 9.24–9.25[16]

- Be always truthful

- Teach his art only to virtuous men

- Follow rules of ritual purification

- Study Vedas with delight

- Never hurt any living creature

- Be gentle but steadfast

- Have self-control

- Be kind, liberal towards everyone

Chapter 8 of the Dharmasutra, states Olivelle, asserts the functions of a Brahmin to be to learn the Vedas, the secular sciences, the Vedic supplements, the dialogues, the epics and the Puranas; to understand the texts and pattern his conduct according to precepts contained in this texts, to undertake Sanskara (rite of passage) and rituals, and lead a virtuous life.[17]

The text lists eight virtues that a Brahmin must inculcate: compassion, patience, lack of envy, purification, tranquility, auspicious disposition, generosity and lack of greed, and then asserts in verse 9.24–9.25, that it is more important to lead a virtuous life than perform rites and rituals, because virtue leads to achieving liberation (moksha, a life in the world of Brahman).[17]

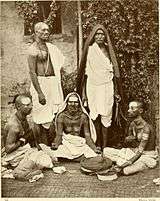

(both paintings by Lady Lawley, 1914)

The later Dharma texts of Hinduism such as Baudhayana Dharmasutra add charity, modesty, refraining from anger and never being arrogant as duties of a Brahmin.[18] The Vasistha Dharmasutra in verse 6.23 lists discipline, austerity, self-control, liberality, truthfulness, purity, Vedic learning, compassion, erudition, intelligence and religious faith as characteristics of a Brahmin.[19] In 13.55, the Vasistha text states that a Brahmin must not accept weapons, poison or liquor as gifts.[20]

The Dharmasastras such as Manusmriti, like Dharmsutras, are codes primarily focussed on how a Brahmin must live his life, and their relationship with a king and warrior class.[21] Manusmriti dedicates 1,034 verses, the largest portion, on laws for and expected virtues of Brahmins.[22] It asserts, for example,

A well disciplined Brahmin, although he knows just the Savitri verse, is far better than an undisciplined one who eats all types of food and deals in all types of merchandise though he may know all three Vedas.

John Bussanich states that the ethical precepts set for Brahmins, in ancient Indian texts, are similar to Greek virtue-ethics, that "Manu's dharmic Brahmin can be compared to Aristotle's man of practical wisdom",[24] and that "the virtuous Brahmin is not unlike the Platonic-Aristotelian philosopher" with the difference that the latter was not sacerdotal.[25]

History

According to Abraham Eraly, "Brahmin as a varna hardly had any presence in historical records before the Gupta Empire era" (3rd century to 6th century CE), when Buddhism dominated the land. "No Brahmin, no sacrifice, no ritualistic act of any kind ever, even once, is referred to" in any Indian texts between third century BCE and the late first century CE. He also states that "The absence of literary and material evidence, however, does not mean that Brahmanical culture did not exist at that time, but only that it had no elite patronage and was largely confined to rural folk, and therefore went unrecorded in history".[26] Their role as priests and repository of sacred knowledge, as well as their importance in the practice of Vedic Shrauta rituals, grew during the Gupta Empire era and thereafter.[26] However, the knowledge about actual history of Brahmins or other varnas of Hinduism in and after the first millennium is fragmentary and preliminary, with little that is from verifiable records or archeological evidence, and much that is constructed from ahistorical Sanskrit works and fiction. Michael Witzel writes,

Toward a history of the Brahmins: Current research in the area is fragmentary. The state of our knowledge of this fundamental subject is preliminary, at best. Most Sanskrit works are a-historic or, at least, not especially interested in presenting a chronological account of India's history. When we actually encounter history, such as in Rajatarangini or in the Gopalavamsavali of Nepal, the texts do not deal with brahmins in great detail.

Normative occupations

_Bhumi_Puja%2C_yajna.jpg)

The Gautama Dharmasutra states in verse 10.3 that it is obligatory on a Brahmin to learn and teach the Vedas.[28] Chapter 10 of the text, according to Olivelle translation, states that he may impart Vedic instructions to a teacher, relative, friend, elder, anyone who offers exchange of knowledge he wants, or anyone who pays for such education.[28] The Chapter 10 adds that a Brahmin may also engage in agriculture, trade, lend money on interest, while Chapter 7 states that a Brahmin may engage in the occupation of a warrior in the times of adversity.[28][29] Typically, asserts Gautama Dharmasutra, a Brahmin should accept any occupation to sustain himself but avoid the occupations of a Shudra, but if his life is at stake a Brahmin may sustain himself by accepting occupations of a Shudra.[29] The text forbids a Brahmin from engaging in the trade of animals for slaughter, meat, medicines and milk products even in the times of adversity.[29]

The Apastamba Dharmasutra asserts in verse 1.20.10 that trade is generally not sanctioned for Brahmins, but in the times of adversity he may do so.[30] The chapter 1.20 of Apastamba, states Olivelle, forbids the trade of the following under any circumstances: human beings, meat, skins, weapons, barren cows, sesame seeds, pepper, and merits.[30]

The 1st millennium CE Dharmasastras, that followed the Dharmasutras contain similar recommendations on occupations for a Brahmin, both in prosperous or normal times, and in the times of adversity.[31] The widely studied Manusmriti, for example, states:

Except during a time of adversity, a Brahmin ought to sustain himself by following a livelihood that causes little or no harm to creatures. He should gather wealth just sufficient for his subsistence through irreproachable activities that are specific to him, without fatiguing his body. – 4.2–4.3

He must never follow a worldly occupation for the sake of livelihood, but subsist by means of a pure, upright and honest livelihood proper to a Brahmin. One who seeks happiness should become supremely content and self controlled, for happiness is rooted in contentment and its opposite is the root of unhappiness. – 4.11–4.12

— Manusmriti, Translated by Patrick Olivelle[32]

The Manusmriti recommends that a Brahmin's occupation must never involve forbidden activities such as producing or trading poison, weapons, meat, trapping birds and others.[33] It also lists six occupations that it deems proper for a Brahmin: teaching, studying, offering yajna, officiating at yajna, giving gifts and accepting gifts.[33] Of these, states Manusmriti, three which provide a Brahmin with a livelihood are teaching, officiating at yajna, and accepting gifts.[34] The text states that teaching is best, and ranks the accepting of gifts as the lowest of the six.[33] In the times of adversity, Manusmriti recommends that a Brahmin may live by engaging in the occupations of the warrior class, or agriculture or cattle herding or trade.[34] Of these, Manusmriti in verses 10.83–10.84 recommends a Brahmin should avoid agriculture if possible because, according to Olivelle translation, agriculture "involves injury to living beings and dependence of others" when the plow digs the ground and injures the creatures that live in the soil.[34][35] However, adds Manusmriti, even in the times of adversity, a Brahmin must never trade or produce poison, weapons, meat, soma, liquor, perfume, milk and milk products, molasses, captured animals or birds, beeswax, sesame seeds or roots.[34]

Actual occupations

Historical records, state scholars, suggest that Brahmin varna was not limited to a particular status or priest and teaching profession.[3][5][39] Historical records from mid 1st millennium CE and later, suggest Brahmins were agriculturalists and warriors in medieval India, quite often instead of as exception.[3][5] Donkin and other scholars state that Hoysala Empire records frequently mention Brahmin merchants "carried on trade in horses, elephants and pearls" and transported goods throughout medieval India before the 14th-century.[40][41]

The Pali Canon depicts Brahmins as the most prestigious and elite non-Buddhist figures.[39] They mention them parading their learning. The Pali Canon and other Buddhist texts such as the Jataka Tales also record the livelihood of Brahmins to have included being farmers, handicraft workers and artisans such as carpentry and architecture.[39][42] Buddhist sources extensively attest, state Greg Bailey and Ian Mabbett, that Brahmins were "supporting themselves not by religious practice, but employment in all manner of secular occupations", in the classical period of India.[39] Some of the Brahmin occupations mentioned in the Buddhist texts such as Jatakas and Sutta Nipata are very lowly.[39] The Dharmasutras too mention Brahmin farmers.[39][43]

According to Haidar and Sardar, unlike the Mughal Empire in Northern India, Brahmins figured prominently in the administration of Deccan Sultanates. Under Golconda Sultanate Telugu Niyogi Brahmins served in many different roles such as accountants, ministers, revenue administration and in judicial service.[44] The Deccan sultanates also heavily recruited Marathi Brahmins at different levels of their administration[45] During the days of Maratha Empire in the 17th and 18th century, the occupation of Marathi Brahmins ranged from administration, being warriors to being de facto rulers[46][47] After the collapse of Maratha empire, Brahmins in Maharashtra region were quick to take advantage of opportunities opened up by the new British rulers. They were the first community to take up Western education and therefore dominated lower level of British administration in the 19th century.[48] Similarly, the Tamil Brahmins were also quick to take up English education during British colonial rule and dominate government service and law.[49]

Eric Bellman states that during the Islamic Mughal Empire era Brahmins served as advisers to the Mughals, later to the British Raj.[50] The East India Company also recruited from the Brahmin communities of Bihar and Awadh (in the present day Uttar Pradesh[51]) for the Bengal army[52][53] Many Brahmins, in other parts of South Asia lived like other varna, engaged in all sorts of professions. Among Nepalese Hindus, for example, Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels report the actual observed professions of Brahmins from 18th- to early 20th-century included being temple priests, minister, merchants, farmers, potters, masons, carpenters, coppersmiths, stone workers, barbers, gardeners among others.[54]

Other 20th-century surveys, such as in the state of Uttar Pradesh, recorded that the primary occupation of almost all Brahmin families surveyed was neither priestly nor Vedas-related, but like other varnas, ranged from crop farming (80 per cent of Brahmins), dairy, service, labour such as cooking, and other occupations.[55][56] The survey reported that the Brahmin families involved in agriculture as their primary occupation in modern times plough the land themselves, many supplementing their income by selling their labor services to other farmers.[55][57]

Brahmins, bhakti movement and social reform movements

Many of the prominent thinkers and earliest champions of the Bhakti movement were Brahmins, a movement that encouraged a direct relationship of an individual with a personal god.[58][59] Among the many Brahmins who nurtured the Bhakti movement were Ramanuja, Nimbarka, Vallabha and Madhvacharya of Vaishnavism,[59] Ramananda, another devotional poet sant.[60][61] Born in a Brahmin family,[60][62] Ramananda welcomed everyone to spiritual pursuits without discriminating anyone by gender, class, caste or religion (such as Muslims).[62][63][64] He composed his spiritual message in poems, using widely spoken vernacular language rather than Sanskrit, to make it widely accessible. His ideas also influenced the founders of Sikhism in 15th century, and his verses and he are mentioned in the Sikh scripture Adi Granth.[65] The Hindu tradition recognises him as the founder of the Hindu Ramanandi Sampradaya,[66] the largest monastic renunciant community in Asia in modern times.[67][68]

Other medieval era Brahmins who led spiritual movement without social or gender discrimination included Andal (9th-century female poet), Basava (12th-century Lingayatism), Dnyaneshwar (13th-century Bhakti poet), Vallabha Acharya (16th-century Vaishnava poet), among others.[69][70][71]

Many 18th and 19th century Brahmins are credited with religious movements that criticised idolatry. For example, the Brahmins Raja Ram Mohan Roy led Brahmo Samaj and Dayananda Saraswati led the Arya Samaj.[72][73]

In Buddhist and Jaina texts

The term Brahmin appears extensively in ancient and medieval Sutras and commentary texts of Buddhism and Jainism. In Buddhist Pali Canon, such as the Majjhima Nikaya and Devadaha Sutta, first written down about 1st century BCE,[74] the Buddha is attributed to be mentioning Jain Brahmins and ascetics, as he describes their karma doctrine and ascetic practices:[75]

The Blessed One [Buddha] said,

"There are, o monks, some ascetics and Brahmins who speak thus and are of such opinion: 'Whatever a particular person experiences, whether pleasant or painful, or neither pleasant nor painful, all this has (...) Thus say, o monks, those free of bonds [Jainas].

"O Niganthas, you ...

Modern scholars state that such usage of the term Brahmin in ancient texts does not imply a caste, but simply "masters" (experts), guardian, recluse, preacher or guide of any tradition.[77][78][79] An alternate synonym for Brahmin in the Buddhist and other non-Hindu tradition is Mahano.[77]

Outside South Asia: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Indonesia

Some Brahmins formed an influential group in Burmese Buddhist kingdoms in 18th- and 19th-century. The court Brahmins were locally called Punna.[82] During the Konbaung dynasty, Buddhist kings relied on their court Brahmins to consecrate them to kingship in elaborate ceremonies, and to help resolve political questions.[82] This role of Hindu Brahmins in a Buddhist kingdom, states Leider, may have been because Hindu texts provide guidelines for such social rituals and political ceremonies, while Buddhist texts do not.[82]

The Brahmins were also consulted in the transmission, development and maintenance of law and justice system outside India.[82] Hindu Dharmasastras, particularly Manusmriti written by the Brahmin Manu, states Anthony Reid,[83] were "greatly honored in Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Cambodia and Java-Bali (Indonesia) as the defining documents of law and order, which kings were obliged to uphold. They were copied, translated and incorporated into local law code, with strict adherence to the original text in Burma and Siam, and a stronger tendency to adapt to local needs in Java (Indonesia)".[83][84][85]

The mythical origins of Cambodia are credited to a Brahmin prince named Kaundinya, who arrived by sea, married a Naga princess living in the flooded lands.[86][87] Kaudinya founded Kambuja-desa, or Kambuja (transliterated to Kampuchea or Cambodia). Kaundinya introduced Hinduism, particularly Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva and Harihara (half Vishnu, half Shiva), and these ideas grew in southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE.[86]

Brahmins have been part of the Royal tradition of Thailand, particularly for the consecration and to mark annual land fertility rituals of Buddhist kings. A small Brahmanical temple Devasathan, established in 1784 by King Rama I of Thailand, has been managed by ethnically Thai Brahmins ever since.[88] The temple hosts Phra Phikhanesuan (Ganesha), Phra Narai (Narayana, Vishnu), Phra Itsuan (Shiva), Uma, Brahma, Indra (Sakka) and other Hindu deities.[88] The tradition asserts that the Thai Brahmins have roots in Hindu holy city of Varanasi and southern state of Tamil Nadu, go by the title Pandita, and the various annual rites and state ceremonies they conduct has been a blend of Buddhist and Hindu rituals. The coronation ceremony of the Thai king is almost entirely conducted by the royal Brahmins.[88][89]

Modern demographics and economic condition

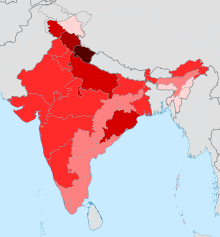

According to 2007 reports, Brahmins in India are about five percent of its total population.[50][90] The Himalayan states of Uttarakhand (20%) and Himachal Pradesh (14%) have the highest percentage of Brahmin population relative to respective state's total Hindus.[90]

According to the Center for the Study of Developing Societies, in 2007 about 50% of Brahmin households in India earned less than $100 a month; in 2004, this figure was 65%.[91]

See also

- Caste system in India

- Vedic priesthood

- Brahmavarta

- List of Brahmins

- Kātouzian, their Zoroastrian counterparts during the time of Jamshid

Notes

-

– Rigveda 10.90.11-2

यत् पुरुषं व्यदधुः कतिधा व्यकल्पयन्।

मुखं किम् अस्य कौ बाहू का ऊरू पादा उच्येते॥११॥

ब्राह्मणो ऽस्य मुखम् आसीद् बाहू राजन्यः कृतः।

ऊरू तद् अस्य यद् वैश्यः पद्भ्यां शूद्रो अजायत॥१२॥

11 When they divided Puruṣa how many portions did they make?

What do they call his mouth, his arms? What do they call his thighs and feet?

12 The Brahmin was his mouth, of both his arms was the Rājanya made.

His thighs became the Vaiśya, from his feet the Śūdra was produced.

References

- Ingold, Tim (1994). Companion encyclopedia of anthropology. London New York: Routledge. p. 1026. ISBN 978-0-415-28604-6.

- James Lochtefeld (2002), Brahmin, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 125

- GS Ghurye (1969), Caste and Race in India, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-205-5, pages 15–18

- Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Springfield, MA, USA: Merriam-Webster. pp. 141–142, 186. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- David Shulman (1989), The King and the Clown, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-00834-9, page 111

- Max Müller, A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 570–571

- Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780520242258.

- Leeming, David Adams; Leeming, Margaret Adams (1994). A Dictionary of Creation Myths. Oxford University Press. pp. 139–144. ISBN 978-0-19510-275-8.

- Jamison, Stephanie; et al. (2014). The Rigveda : the earliest religious poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- Mahendra Kulasrestha (2007), The Golden Book of Upanishads, Lotus, ISBN 978-81-8382-012-7, page 21

- Mohr and Fear (2015), World Religions: The History, Issues, and Truth, ISBN 978-1-5035-0369-4, page 81

- Robert Hume, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 3.1, Oxford University Press, pages 107–109

- Kulkarni, A.R. (1964). "Social and Economic Position of Brahmins in Maharashtra in the Age of Shivaji". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 26: 66–67. JSTOR 44140322.

- Patrick Olivelle (2011), Ascetics and Brahmins: Studies in Ideologies and Institutions, Anthem, ISBN 978-0-85728-432-7, page 60

- RC Prasad (2014), The Upanayana: The Hindu Ceremonies of the Sacred Thread

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, page 91

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, pages 90–91

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, pages 136–137

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, pages 267–268

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, page 284

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, pages 16, 62–65

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, pages 41, for specific examples see 132–134

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, page 101

- John Bussanich (2014), Ancient Ethics (Editors: Jörg Hardy and George Rudebusch), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 978-3-89971-629-0, pages 38, 33–52, Quote: "Affinities with Greek virtue ethics are also noteworthy. Manu's dharmic Brahmin can be compared to Aristotle's man of practical wisdom, who exercises moral authority because he feels the proper emotions and judges difficult situations correctly, when moral rules and maxims are unavailable".

- John Bussanich (2014), Ancient Ethics (Editors: Jörg Hardy and George Rudebusch), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 978-3-89971-629-0, pages 44–45

- Abraham Eraly (2011), The First Spring: The Golden Age of India, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4, page 283

- Michael Witzel (1993) Toward a History of the Brahmins, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, No. 2, pages 264–268

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, page 94

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, page 89

- Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7, page 31

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, pages 124–126

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, page 124

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, pages 125, 211–212

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4, page 212

- Patrick Olivelle (2011), Ascetics and Brahmins: Studies in Ideologies and Institutions, Anthem, ISBN 978-0-85728-432-7, page 39

- Johannes de Kruijf and Ajaya Sahoo (2014), Indian Transnationalism Online: New Perspectives on Diaspora, ISBN 978-1-4724-1913-2, page 105, Quote: "In other words, according to Adi Shankara's argument, the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta stood over and above all other forms of Hinduism and encapsulated them. This then united Hinduism; (...) Another of Adi Shankara's important undertakings which contributed to the unification of Hinduism was his founding of a number of monastic centers."

- Shankara, Student's Encyclopædia Britannica - India (2000), Volume 4, Encyclopædia Britannica (UK) Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5, page 379, Quote: "Shankaracharya, philosopher and theologian, most renowned exponent of the Advaita Vedanta school of philosophy, from whose doctrines the main currents of modern Indian thought are derived."

David Crystal (2004), The Penguin Encyclopedia, Penguin Books, page 1353, Quote: "[Shankara] is the most famous exponent of Advaita Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy and the source of the main currents of modern Hindu thought." - Christophe Jaffrelot (1998), The Hindu Nationalist Movement in India, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-10335-0, page 2, Quote: "The main current of Hinduism - if not the only one - which became formalized in a way that approximates to an ecclesiastical structure was that of Shankara".

- Greg Bailey and Ian Mabbett (2006), The Sociology of Early Buddhism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-02521-8, pages 113–115 with footnotes

- RA Donkin (1998), Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-fishing, American Philosophical Society, ISBN 978-0-87169-224-5, page 166

- SC Malik (1986), Determinants of Social Status in India, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, ISBN 978-81-208-0073-1, page 121

- Stella Kramrisch (1994), Exploring India's Sacred Art, Editor: Stella Miller, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1208-6, pages 60–64

- RITSCHL, Eva (1980). "Brahmanische Bauern. Zur Theorie und Praxis der brahmanischen Ständeordnung im alten Indien". Altorientalische Forschungen (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH. 7 (JG): 177–187. doi:10.1524/aofo.1980.7.jg.177.

- Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (2015). Sultans of Deccan Indian 1500–1700 (1 ed.). New Haven, CT, USA: Museum Of Metropolitan Art. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-300-21110-8. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Gordon, Stewart (1993). Cambridge History of India: The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995). The Satara Raj, 1818–1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture - Sumitra Kulkarni. ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "India : Rise of the peshwas - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Hanlon, Rosilind (1985). Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and low caste protest in nineteenth-century Western India. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0 521 52308 7. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Anil Seal (2 September 1971). The Emergence of Indian Nationalism: Competition and Collaboration in the Later Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-09652-2.

- Eric Bellman, Reversal of Fortune Isolates India's Brahmins, The Wall Street Journal (29 December 2007)

- Gyanendra Pandey (2002). The Ascendancy of the Congress in Uttar Pradesh: Class, Community and Nation in Northern India, 1920-1940. Anthem Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84331-057-0.

- David Omissi (27 July 2016). The Sepoy and the Raj: The Indian Army, 1860-1940. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-349-14768-7.

- Groseclose, Barbara (1994). British sculpture and the Company Raj : church monuments and public statuary in Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay to 1858. Newark, Del.: University of Delaware Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-87413-406-4. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels (2008), Bel-Frucht und Lendentuch: Mädchen und Jungen in Bhaktapur Nepal, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pages 23 (table), for context and details see 16–36

- Noor Mohammad (1992), New Dimensions in Agricultural Geography, Volume 3, Concept Publishers, ISBN 81-7022-403-9, pages 45, 42–48

- Ramesh Bairy (2010), Being Brahmin, Being Modern, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-58576-7, pages 86–89

- G Shah (2004), Caste and Democratic Politics in India, Anthem, ISBN 978-1-84331-085-3, page 40

- Sheldon Pollock (2009), The Language of the Gods in the World of Men, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520260030, pages 423-431

- Oliver Leaman (2002). Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings. Routledge. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-134-68919-4.;

S. M. Srinivasa Chari (1994). Vaiṣṇavism: Its Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Discipline. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-81-208-1098-3. - Ronald McGregor (1984), Hindi literature from its beginnings to the nineteenth century, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02413-6, pages 42–44

- William Pinch (1996), Peasants and Monks in British India, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6, pages 53–89

- David Lorenzen, Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History, ISBN 978-81-902272-6-1, pages 104–106

- Gerald James Larson (1995), India's Agony Over Religion, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2412-4, page 116

- Julia Leslie (1996), Myth and Mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian Tradition, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-0303-6, pages 117–119

- Winnand Callewaert (2015), The Hagiographies of Anantadas: The Bhakti Poets of North India, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138-86246-3, pages 405–407

- Schomer and McLeod (1987), The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3, pages 4–6

- Selva Raj and William Harman (2007), Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-6708-4, pages 165–166

- James G Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4, pages 553–554

- John Stratton Hawley (2015), A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-18746-7, pages 304–310

- Rachel McDermott (2001), Singing to the Goddess: Poems to Kālī and Umā from Bengal, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513434-6, pages 8–9

- "Mahima Dharma, Bhima Bhoi and Biswanathbaba" Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, An Orissa movement by Brahmin Mukunda Das (2005)

- Noel Salmond (2004), Hindu iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and nineteenth-century polemics against idolatry, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, ISBN 0-88920-419-5, pages 65–68

- Dorothy Figueira (2002), Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority through Myths of Identity, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-5531-9, pages 90–117

- Donald Lopez (2004). Buddhist Scriptures. Penguin Books. pp. xi–xv. ISBN 978-0-14-190937-0.

- Piotr Balcerowicz (2015). Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism. Routledge. pp. 149–150 with footnote 289 for the original mentioning Tapas. ISBN 978-1-317-53853-0.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2005), Devadaha Sutta: At Devadaha, M ii.214

- Padmanabh S. Jaini (2001). Collected Papers on Buddhist Studies. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-208-1776-0.

- K N Jayatilleke (2013). Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge. Routledge. pp. 141–154, 219, 241. ISBN 978-1-134-54287-1.

- Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8.

- Martin Ramstedt (2003), Hinduism in Modern Indonesia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1533-6, page 256

- Martin Ramstedt (2003), Hinduism in Modern Indonesia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1533-6, page 80

- Leider, Jacques P. (2005). "Specialists for Ritual, Magic and Devotion: The Court Brahmins of the Konbaung Kings". The Journal of Burma Studies. 10: 159–180. doi:10.1353/jbs.2005.0004.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anthony Reid (1988), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680: The lands below the winds, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-04750-9, pages 137–138

- Victor Lieberman (2014), Burmese Administrative Cycles, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-61281-2, pages 66–68; Also see discussion of 13th century Wagaru Dhamma-sattha / 11th century Manu Dhammathat manuscripts discussion

- On Laws of Manu in 14th century Thailand's Ayuthia kingdom named after Ayodhya, see David Wyatt (2003), Thailand: A Short History, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-08475-7, page 61;

Robert Lingat (1973), The Classical Law of India, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-01898-3, pages 269–272 - Trevor Ranges (2010), Cambodia, National Geographic, ISBN 978-1-4262-0520-0, page 48

- Jonathan Lee and Kathleen Nadeau (2010), Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife, Volume 1, ABC, ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5, page 1223

- HG Quadritch Wales (1992), Siamese State Ceremonies, Curzon Press, ISBN 978-0-7007-0269-5, pages 54–63

- Boreth Ly (2011), Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia (Editors: Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade), Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-4311-16-8, pages 461–475

- "Brahmins In India". Outlook India. 2007.

- Eric Bellman, Reversal of Fortune Isolates India's Brahmins, Wall street Journal (December 29, 2007).

Further reading

- Baldev Upadhyaya, Kashi Ki Panditya Parampara, Sharda Sansthan, Varanasi, 1985.

- Christopher Alan Bayly, Rulers, Townsmen, and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Anand A. Yang, Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar, University of California Press, 1999.

- M. N. Srinivas, Social Change in Modern India, Orient Longman, Delhi, 1995.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brahmins. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Brahmin |

- Brahmins and Pariah, An appeal and record of colonial era conflict in Bengal

- The wisdom of the Brahmin, Friedrich Ruckert (translated from German by Charles Brooks)

.jpg)

_met_offergereedschap_Bali_TMnr_10001214.jpg)