Bothnian Bay

The Bothnian Bay or Bay of Bothnia (Swedish: Bottenviken; Finnish: Perämeri) is the northernmost part of the Gulf of Bothnia, which is in turn the northern part of the Baltic Sea. The land holding the bay is still rising after the weight of ice-age glaciers has been removed, and within 2,000 years the bay will be a large freshwater lake. The bay today is fed by several large rivers, and is relatively unaffected by tides, so has low salinity. It freezes each year for up to six months. Compared to other parts of the Baltic it has little plant or animal life.

| Bothnian Bay | |

|---|---|

| Bay of Bothnia | |

The rocky shoreline of Ohtakari, in the southeast of the bay | |

Bothnian Bay Location in Europe | |

| Location | Fennoscandia |

| Coordinates | 65°N 023°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Primary outflows | Bothnian Sea |

| Catchment area | 260,675 km2 (100,647 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Finland, Sweden, Norway |

| Surface area | 36,800 km2 (14,200 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 43 m (141 ft) |

| Max. depth | 147 m (482 ft) |

| Water volume | 1,490 km3 (360 cu mi) |

| Frozen | 110–190 days annually |

Extent

The bay is divided from the Bothnian Sea, the southern part of the Gulf of Bothnia, by the Northern Quark (Kvarken) strait. The Northern Quark has a greatest depth of 65 metres (213 ft), with two ridges that are just 25 metres (82 ft) deep. It lies between a group of islands off Vaasa in Finland and another group at Holmöarna in Sweden.[1] The bay is bounded by Finland to the east and Sweden to the west. The bay is asymmetric, with a smoother and shallower bottom slope on the Finnish side, and a deeper bottom with a steeper and more rugged coast on the Swedish side.[1]

The Bothnian Bay has a catchment area of 260,675 square kilometres (100,647 sq mi). Of this, 56% lies in Finland, 44% in Sweden and less than 1% in Norway.[2] The catchment contains about 11,500,000 hectares (28,000,000 acres) of forest, split roughly equally between Sweden and Finland.[3]

The average depth is 41 metres (135 ft). The Luleå Deep is the deepest part of the bay, at 146 metres (479 ft), southeast of the town of Luleå.[4] On the Finnish side the average depth is 30 metres (98 ft). The deepest part is near the island of Lönkytin, with a depth of 50 metres (160 ft).[5]

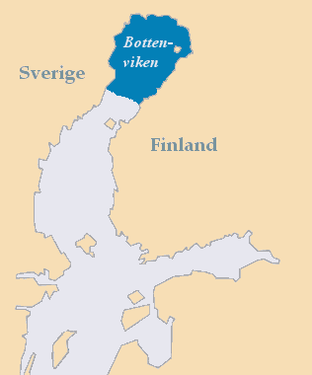

Map of the Gulf of Bothnia showing location of Bothnian Bay (shaded and labelled Bottenviken)

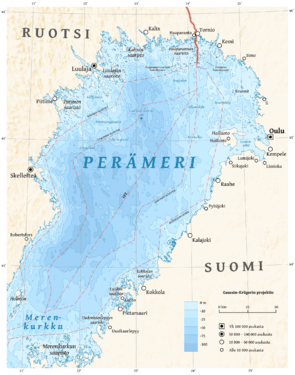

Map of the Gulf of Bothnia showing location of Bothnian Bay (shaded and labelled Bottenviken) Finnish map of the bay – click to enlarge

Finnish map of the bay – click to enlarge Satellite image of Fennoscandia with sea ice covering the Bothnian Bay (white region in center)

Satellite image of Fennoscandia with sea ice covering the Bothnian Bay (white region in center)

Isostatic rebound

The bay lies in the area in Northern Europe where the ice was at its thickest during the last ice age.[6] The Bay of Bothnia was under ice until the "Ancylus Lake" period (7500–6000 BC), when the ice sheet withdrew to the mountains of Northern Scandinavia.[7] The land is now rising by post-glacial rebound at the highest rate in the Baltic Sea, at an estimated rate of 9 millimetres (0.35 in) a year.[8] Today the Bothnian Bay lies around 300 metres (980 ft) higher than it did at the end of the Ice age.[6] The local population has seen the sea retreating during their lifetimes from piers and boathouses, leaving them stranded on land. Some former islands such as Porsön and Hertsön near the city of Luleå are still called islands, but are now connected to the mainland.[9]

The maximum depth at the Kvarken sound today is around 20 metres (66 ft). In not less 2,000 years the exit from the bay at Kvarken will be raised above sea level, which will result in it becoming Europe's largest lake.[10]

Hydrology

The Bothnian Bay has a harsher environment than other parts of the greater Baltic Sea.[11] The bay is ice-covered for 110 to 190 days each year.[12] Tides have little effect, but high winds driving the water from the south or north may cause the water level to rise or fall by 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in).[9]

Major rivers that flow into the bay include:

| River | Country | Discharge |

|---|---|---|

| Kemijoki | Finland | 556 m3/s (19,600 cu ft/s) |

| Lule River | Sweden | 506 m3/s (17,900 cu ft/s) |

| Torne River | Sweden and Finland | 388 m3/s (13,700 cu ft/s) |

| Kalix River | Sweden | 295 m3/s (10,400 cu ft/s) |

| Oulujoki | Finland | 250 m3/s (8,800 cu ft/s) |

| Pite River | Sweden | 167 m3/s (5,900 cu ft/s) |

| Skellefte River | Sweden | 162 m3/s (5,700 cu ft/s) |

| Iijoki | Finland | 164 m3/s (5,800 cu ft/s) |

The salinity is only about 0.2 psu in the northern part of the bay, dropping almost to zero in some of the archipelagos with large river inflows.[13] The low salinity and cold temperatures in winter results in ice that is considerably stronger than more saline or warmer ice.[14]

Islands

If an island is defined as an area of land more than 20 square metres (220 sq ft) that is surrounded by water, the Bay of Bothnia has 4,001 islands.[9] The largest island is Hailuoto.[1] The north of the bay contains a large archipelago area.[1] The Swedish portion of this area is the Norrbotten archipelago.[15] This is divided into the Piteå, Luleå, Kalix and Haparanda archipelagos.[16] Many of the islands are uninhabited and in a natural state.[17] In the winter the larger islands may be accessed via ice roads. Some of them are inhabited or have seasonal fishing villages used by people from the mainland.[9]

The Swedish Haparanda Archipelago National Park (Swedish: Haparanda skärgårds nationalpark) occupies the Haparanda group of islands, bordering the Finnish Bothnian Bay National Park. It includes the larger islands of Sandskär and Seskar Furö, and some smaller islands and skerries. All of these islands have emerged in the last 1,500 years as the bed of the bay has risen.[18] The Bay of Bothnia National Park in the Finnish section (Finnish: Perämeren kansallispuisto, Swedish: Bottenvikens nationalpark), established in 1991, is located in the archipelago offshore from Tornio and Kemi. It covers 157 square kilometres (61 sq mi) of which about 2.5 square kilometres (0.97 sq mi) is land.[19]

Ecology

The Quark ridge at the south of the bay defines the dividing line beyond which many salt water species are unable to survive.[20] Instead of the red and brown algae found further south, the bay has predominantly green algae and phanerogams.[11] Annual plant species are almost completely dominant. The only perennials are a few specimens of the freshwater cryptogram Isoetes echinospora and the moss Fontinalis dalecarlica.[21] Often the green algae have a dense covering of epiphytic diatoms.[22] The shores, beaches and shallows include a variety of northern plant species including the endemic yellow hair grass (Deschampsia bottnica).[9]

The only filter feeders are Ephydatia and, at the river mouths, small numbers of freshwater mussels.[22] Bivalves make up 9% of animal biomass. Crustaceans, mostly Saduria entomon make up 45% and gastropoda 30%.[23] The gastropoda are grazing snails related to freshwater species.[24]

Fish species found in the area's lakes and rivers also live in the bay, including roach, perch, pike and grayling.[20]

Ringed seal, grey seal, cod, herring and salmon may also be found in the bay.[9] In the 16th century seals were hunted in the Bay of Bothnia. Ringed seals were captured using nets in the inshore open water, and were stalked and captured in their dens or at breathing holes. Both grey and ringed seals were hunted along the edge of the ice.[25] Wild vendace roe harvested from the Kalix River, known as Kalix Löjrom or as sea gold, is a delicacy with a European protected designation of origin.[26]

Birdlife includes the black guillemot, velvet scoter, oystercatcher, lesser black-backed gull, western capercaillie and willow ptarmigan. Moose and hare are found on the islands, as on the mainland.[9]

Occasionally, whales have been observed in Bothnian Sea[27] and remains of extinct Atlantic gray whale was found from Gräsö[28] while it is not clear whether or not whales might once reached Bothnian Bay historically.

Population

Ports on the Finnish side include Haukipudas, Jakobstad, Kemi, Kokkola, Oulu, Raahe and Tornio.[29] The largest towns by population on the Finnish side as of 2013 were Oulu (192,680), Tornio (22,374), Kemi (22,157), Kempele (16,549), Raahe (25,641), Kalajoki (12,637), Kokkola (46,697) and Jakobstad (19,636).[30] In Finland the catchment area included about 544,000 hectares (1,340,000 acres) of arable land as of 1993. There were four Finnish pulp and paper mills, of which two (Veitsiluoto Oy and Metsä Botnia Oy) were producing bleached kraft paper.[31]

On the Swedish side ports include Haparanda, Karlsborg, Kalix, Luleå, Piteå and Skellefteå.[29] The largest towns on the Swedish side as of 2013 were Luleå (74,000), Skellefteå (71,641), Piteå (40,860) and Kalix (16,926). Luleå is the largest city in Norrbotten, with the largest airport. The 1,312 islands of the Luleå archipelago are an important tourist attraction, as is the Gammelstad church village, listed as a Unesco World Heritage site.[26] As of 1993 there were about 113,000 hectares (280,000 acres) of arable land in the Swedish part of the catchment basin, mostly used for small-scale low-intensity farming. There were five pulp and paper mills, of which one produced bleached kraft paper.[31]

In the late 1960s the bay was being used to transport fuel oil to the Finnish settlements around the bay. In 1968 about 950,000 tons of cellulose and 230,600 tons of paper and cardboard were exported, a figure that was rising.[32] In 1968 ships calling at the Finnish ports carried about 388,872 tons of iron bars and 64,326 tons of steel sheets. Mining and mineral products such as coal and ore were carried to and from the ports, and steel products were exported.[33] Sea transport continued throughout the winter.[32] In 1993 there were two non-ferrous heavy metal smelters, in Rönnskär and Kokkola, emitting significant quantities of heavy metals. Efforts were being made to reduce emissions. The drainage basin also held three iron and steel plants and a number of mines.[31]

Human activities have affected the fragile sub-arctic environment. Dredging and other activities related to sea transport affect marine life. Agriculture, forestry and peat mining in the catchment basin add nutrients to the bay, affecting the ecological balance, while pollutants are delivered from steel mills and from pulp and paper mills around the bay, as well as from sewage treatment plants.[34] Steel mills and stainless steel plants may have released nickel and chromium.[2] Efforts have been made to reduce pollution through improved technology, but some areas along the Finnish coastline show evidence of eutrophication.[34] Compared to other parts of the Baltic, higher levels of nitrate have been found in the Bothnian Bay and lower levels of phosphate and silicates.[35]

Gallery

The bridge to Seskarö, Sweden

The bridge to Seskarö, Sweden Finnish icebreaker MSV Fennica in the Bay

Finnish icebreaker MSV Fennica in the Bay- Looking back from the Icebreaker Sampo near Kemi, Finland

Old mill buildings and harbour in Toppila, Oulu, Finland

Old mill buildings and harbour in Toppila, Oulu, Finland Buildings and the birdwatching tower at Varessäikkä harbour, Siikajoki, Finland

Buildings and the birdwatching tower at Varessäikkä harbour, Siikajoki, Finland Old fisherman's cottage

Old fisherman's cottage Lönkytin island

Lönkytin island The island of Kahvankari in Oulu, Finland

The island of Kahvankari in Oulu, Finland- The eastern shore of the Kellon Kraaseli island, Haukipudas, Finland

Bothnian Bay in Kemi, Finland

Bothnian Bay in Kemi, Finland Sunset at Hiekkasärkät, Kalajoki, Finland

Sunset at Hiekkasärkät, Kalajoki, Finland

References

Citations

- Leppäranta & Myrberg 2009, p. 55.

- Szefer 2002, p. 11.

- Baltic Sea Joint Comprehensive Environmental Action, pp. 2–3.

- Leppäranta & Myrberg 2009, p. 56.

- Merikartta Perämeri osa 57.

- Røed 2011.

- Leppäranta & Myrberg 2009, p. 11.

- Nesje 2006.

- About the Bay ... Bottenvikens skärgård.

- Tikkanen, Matti; Oksanen, Juha (2002). "Late Weichselian and Holocene shore displacement history of the Baltic Sea in Finland". Fennia. 180 (1–2). Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Eleftheriou, Smith & Ansell 1995, p. 23.

- Müller 1982, p. 8.

- Eleftheriou, Smith & Ansell 1995, p. 24.

- Mäkinen 1972, p. 3.

- Ankre 2005, p. 8.

- Index: bottenviken.se.

- Sweden: Rough Guides 2003 403.

- Haparanda Skärgård National Park.

- Bay of Bothnia National Park.

- Bottniska viken: Stockholms universitets.

- Eleftheriou, Smith & Ansell 1995, p. 25.

- Eleftheriou, Smith & Ansell 1995, p. 26.

- Eleftheriou, Smith & Ansell 1995, p. 33.

- Eleftheriou, Smith & Ansell 1995, p. 29.

- Kvist 1991, p. 339.

- Swedish Lapland: The destination.

- Yle Uutiset. 2006. Humpback Whale Spotted in Gulf of Bothnia. Retrieved on September 05, 2017

- Jones L.M..Swartz L.S.. Leatherwood S.. The Gray Whale: Eschrichtius Robustus. "Eastern Atlantic Specimens". pp 41-44. Academic Press. Retrieved on September 05, 2017

- Bothnian Bay: Port Map.

- Väestötietojärjestelmä Rekisteritilanne.

- Baltic Sea Joint Comprehensive Environmental Action, pp. 2-3.

- Mäkinen 1972, p. 4.

- Mäkinen 1972, p. 5.

- Laine 2013, p. 1.

- Szefer 2002, p. 134.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bothnian Bay. |

Sources

- "About the Bay of Bothnia". Bottenvikens skärgård. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- Ankre, Rosemarie (2005). "A Case Study of the Luleå archipelago, Sweden" (PDF). Mid-Sweden University. Retrieved 2013-10-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Baltic Sea Joint Comprehensive Environmental Action Programme". Helsinki: Balt. Sea Environ. Proc. No. 48. 1993. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- "Bay of Bothnia National Park". Lapland Travel Info. Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- "Bothnian Bay: Port Map". World Port Source. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- "Bottniska viken". Havet.nu. Stockholms universitets Östersjöcentrum and Umeå marina forskningscentrum. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- Eleftheriou, Anastasios; Smith, Christopher; Ansell, Alan D. (1995). Biology and Ecology of Shallow Coastal Waters: Proceedings of the 28th European Marine Biology Symposium, Institute of Marine Biology of Crete, Iraklio, Crete, 1993. Olsen & Olsen. ISBN 978-87-85215-28-4. Retrieved 2013-09-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Haparanda Skärgård National Park". Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- "Index". bottenviken.se. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- Kvist, Roger (October 1991). "Sealing and sealing methods in the Bay of Bothnia, 1551–70". Polar Record. 27 (163): 339–344. doi:10.1017/s0032247400013097. ISSN 1475-3057.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laine, Anne (2013). "Bothnian Bay Life – Integrated Management System for the Bothnian Bay". Retrieved 2013-10-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leppäranta, Matti; Myrberg, Kai (2009-03-20). Physical Oceanography of the Baltic Sea. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-540-79703-6. Retrieved 2013-10-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mäkinen, Pentti (September 1972). "Winter Navigation in the Bothnian Bay and the Iceworthiness of Merchant Vessels" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2013-10-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merikartta Perämeri osa 57 (Nautical chart of the Bay of Bothnia 57)

- Müller, K. (1982-04-30). Coastal Research in the Gulf of Bothnia. Springer. ISBN 978-90-6193-098-3. Retrieved 2013-09-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nesje, Atle (2006-05-30). "Isbreene smelter – havnivået stiger". CICERO. Archived from the original on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nordström, Marie (4 December 2009). "Perämeri". Bothnian Bay Life project. Archived from the original on 28 September 2005. Retrieved 2013-09-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Røed, Lars-Ludvig (4 November 2011), "Norge blir stadig høyere", AftenpostenCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sweden. Rough Guides. 2003. ISBN 978-1-84353-066-4. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- "Swedish Lapland: The destination". Swedish Lapland DMC. Archived from the original on 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- Szefer, P. (2002-01-30). Metals, Metalloids and Radionuclides in the Baltic Sea Ecosystem. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-053633-0. Retrieved 2013-09-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Väestötietojärjestelmä Rekisteritilanne" (in Finnish and Swedish). Population Register Center of Finland. 31 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-10-02.