Bosporus

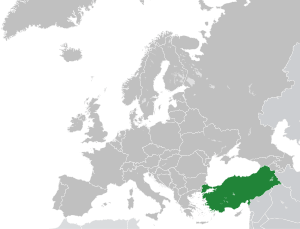

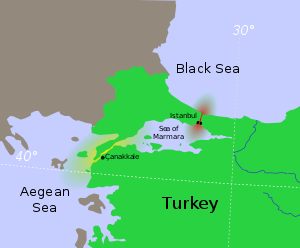

The Bosporus (/ˈbɒspərəs/) or Bosphorus (/-pər-, -fər-/;[1] Ancient Greek: Βόσπορος Bosporos [bós.po.ros]; also known as the Strait of Istanbul; Turkish: İstanbul Boğazı, colloquially Boğaz) is a narrow, natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in northwestern Turkey. It forms part of the continental boundary between Europe and Asia, and divides Turkey by separating Anatolia from Thrace. It is the world's narrowest strait used for international navigation. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, and, by extension via the Dardanelles, the Aegean and Mediterranean seas.

| Bosporus İstanbul Boğazı | |

|---|---|

Bosporus İstanbul Boğazı | |

| Coordinates | 41°07′10″N 29°04′31″E |

| Type | strait |

| Basin countries | Turkey |

| Max. length | 31 km (19 mi) |

| Min. width | 700 m (2,300 ft) |

| Max. depth | 110 m (360 ft) |

Most of the shores of the strait, except for those in the north, are heavily settled, straddled by the city of Istanbul's metropolitan population of 17 million inhabitants extending inland from both coasts.

Together with the Dardanelles, the Bosporus forms the Turkish Straits.

Name

The name of the channel comes from the Ancient Greek Βόσπορος (Bósporos), which was folk-etymologised as βοὸς πόρος, i.e. "cattle strait" (or "Ox-ford"[2]), from the genitive of boûs βοῦς 'ox, cattle' + poros πόρος 'passage', thus meaning 'cattle-passage', or 'cow passage'.[3] This is in reference to the mythological story of Io, who was transformed into a cow, and was subsequently condemned to wander the Earth until she crossed the Bosporus, where she met the Titan Prometheus, who comforted her with the information that she would be restored to human form by Zeus and become the ancestress of the greatest of all heroes, Heracles (Hercules).

The site where Io supposedly went ashore was near Chrysopolis (present-day Üsküdar), and was named Bous 'the Cow'. The same site was also known as Damalis (Δάμαλις), as it was where the Athenian general Chares had erected a monument to his wife Damalis, which included a colossal statue of a cow (the name δαμάλις translating to 'heifer').[4]

The English spelling with -ph-, Bosfor has no justification in the ancient Greek name, and dictionaries prefer the spelling with -p-[1] but -ph- occurs as a variant in medieval Latin (as Bosfor, and occasionally Bosforus, Bosferus), and in medieval Greek sometimes as Βόσφορος,[5] giving rise to the French form Bosphore, Spanish Bósforo and Russian Босфор. The 12th century Greek scholar John Tzetzes calls it Damaliten Bosporon (after Damalis), but he also reports that in popular usage the strait was known as Prosphorion during his day,[6] the name of the most ancient northern harbour of Constantinople.

Historically, the Bosporus was also known as the "Strait of Constantinople", or the Thracian Bosporus, in order to distinguish it from the Cimmerian Bosporus in Crimea. These are expressed in Herodotus's Histories, 4.83; as Bosporus Thracius, Bosporus Thraciae, and Βόσπορος Θρᾴκιος (Bósporos Thráikios), respectively. Other names by which the strait is referenced by Herodotus include Chalcedonian Bosporus (Bosporus Chalcedoniae, Βοσπορος της Χαλκηδονιης [Bosporos tes Khalkedonies], Herodotus 4.87), or Mysian Bosporus (Bosporus Mysius).[7]

The term eventually came to be used as common noun βόσπορος, meaning "a strait", and was also formerly applied to the Hellespont in Classical Greek by Aeschylus and Sophocles.

Geography

As a maritime waterway, the Bosporus connects various seas along the Eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Near East, and Western Eurasia, and specifically connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara. The Marmara further connects to the Aegean and Mediterranean seas via the Dardanelles. Thus, the Bosporus allows maritime connections from the Black Sea all the way to the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean via Gibraltar, and the Indian Ocean through the Suez Canal, making it a crucial international waterway, in particular for the passage of goods coming in from Russia.

Formation

The exact cause and date of the formation of the Bosporus remain the subject of debate among geologists. One recent hypothesis, dubbed the Black Sea deluge hypothesis, which was launched by a study of the same name in 1997 by two scientists from Columbia University, postulates that the Bosporus was flooded around 5600 BC (revised to 6800 BC in 2003) when the rising waters of the Mediterranean Sea and the Sea of Marmara breached through to the Black Sea, which at the time, according to the hypothesis, was a low-lying body of fresh water.

Many geologists, however, claim that the strait is much older, even if relatively young on a geologic timescale.

From the perspective of ancient Greek mythology, it was said that colossal floating rocks known as the Symplegades, or Clashing Rocks, once occupied the hilltops on both sides of the Bosporus, and destroyed any ship that attempted passage of the channel by rolling down the strait's hills and violently crushing all vessels between them. The Symplegades were defeated when the hero Jason obtained successful passage, whereupon the rocks became fixed, and Greek access to the Black Sea was opened.

Present morphology

The limits of the Bosporus are defined as the connecting line between the lighthouses of Rumeli Feneri and Anadolu Feneri in the north, and between the Ahırkapı Feneri and the Kadıköy İnciburnu Feneri in the south. Between these limits, the strait is 31 km (17 nmi) long, with a width of 3,329 m (1.798 nmi) at the northern entrance and 2,826 m (1.526 nmi) at the southern entrance. Its maximum width is 3,420 m (1.85 nmi) between Umuryeri and Büyükdere Limanı, and minimum width 700 m (0.38 nmi) between Kandilli Point and Aşiyan.

The depth of the Bosporus varies from 13 to 110 m (43 to 361 ft) in midstream with an average of 65 m (213 ft). The deepest location is between Kandilli and Bebek with 110 m (360 ft). The shallowest locations are off Kadıköy İnciburnu on the northward route with 18 m (59 ft) and off Aşiyan Point on the southward route with 13 m (43 ft).[8]

The smallest section is on a sill located in front of Dolmabahçe Palace. It is around 38 000 square meter. The Southbound flow is 16 000 m3/s (fresh water at surface) and the northbound flow is 11 000 m3/s (salt water near bottom).[9] Some even speak about a Black Sea undersea river.

The Golden Horn is an estuary off the main strait that historically acted as a moat to protect Old Istanbul from attack, as well as providing a sheltered anchorage for the imperial navies of various empires until the 19th century, after which it became a historic neighborhood at the heart of the city, popular with tourists and locals alike.

Newer explorations

It had been known since before the 20th century that the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara flow into each other in a geographic example of "density flow", and in August 2010, a continuous 'underwater channel' of suspension composition was discovered to flow along the floor of the Bosporus, which would be the sixth largest river on Earth if it were to be on land.[10] The study of the water and wind erosion of the straits relates to that of its formation. Sections of the shore have been reinforced with concrete or rubble and sections of the strait prone to deposition are periodically dredged.

The 2010 team of scientists, led by the University of Leeds, used a robotic "yellow submarine" to observe detailed flows within an "undersea river", scientifically referred to as a submarine channel,[10] for the first time. Submarine channels are similar to land rivers, but they are formed by density currents—underwater flow mixtures of sand, mud and water that are denser than sea water and so sink and flow along the bottom. These channels are the main transport pathway for sediments to the deep sea where they form sedimentary deposits. These deposits ultimately hold not only untapped reserves of gas and oil, they also house important secrets—from clues on past climate change to the ways in which mountains were formed.[10]

The team studied the detailed flow within these channels and findings included:

The channel complex and the density flow provide the ideal natural laboratory for investigating and detailing the structure of the flow field through the channel. Our initial findings show that the flow in these channels is quite different to the flow in river channels on land. Specifically, as flow moves around a bend it spirals in the opposite direction in the deep sea compared to the spiral found in river channels on land. This is important in understanding the sedimentology and layers of sediment deposited by these systems.[11]

The central tenet of the Black Sea deluge hypothesis is that as the ocean rose 72.5 metres (238 ft) at the end of the last Ice Age when the massive ice sheets melted, the sealed Bosporus was overtopped in a spectacular flood that increased the then fresh water Black Sea Lake 50%, and drove people from the shores for many months. This was supported by findings of undersea explorer Robert Ballard, who discovered settlements along the old shoreline; scientists dated the flood to 7500 BP or 5500 BC from fresh-salt water microflora. The peoples driven out by the constantly rising water, which must have been terrifying and inexplicable, spread to all corners of the Western world carrying the story of the Great Flood, which is how it probably entered most religions. As the waters surged, they scoured a network of sea-floor channels less resistant to denser suspended solids in liquid, which remains a very active layer today.

The first images of these submarine channels were obtained in 1999, showing them to be of great size[12] during a NATO SACLANT Undersea Research project using jointly the NATO RV Alliance, and the Turkish Navy survey ship Çubuklu. In 2002, a survey was carried out on board the Ifremer RV Le Suroit for BlaSON project (Lericolais, et al., 2003[13]) completed the multibeam mapping of this underwater channel fan-delta. A complete map was published in 2009[14] using these previous results with high quality mapping obtained in 2006 (by researchers at Memorial University of Newfoundland who are project partners in this study).

The team will use the data obtained to create innovative computer simulations that can be used to model how sediment flows through these channels. The models the team will produce will have broad applications, including inputting into the design of seafloor engineering by oil and gas companies.

The project was led by Jeff Peakall and Daniel Parsons at the University of Leeds, in collaboration with the University of Southampton, Memorial University of Newfoundland, and the Institute of Marine Sciences. The survey was run and coordinated from the Institute of Marine Sciences research ship, the R/V Koca Piri Reis.

History

As part of the only passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, the Bosporus has always been of great importance from a commercial and military point of view, and remains strategically important today. It is a major sea access route for numerous countries, including Russia and Ukraine. Control over it has been an objective of a number of conflicts in modern history, notably the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), as well as of the attack of the Allied Powers on the Dardanelles during the 1915 Battle of Gallipoli in the course of World War I.

Ancient Greek, Persian, Roman and Byzantine eras (pre-1453)

_by_Florentine_cartographer_Cristoforo_Buondelmonte.jpg)

The strategic importance of the Bosporus dates back millennia. In the 5th century BC the Greek city-state of Athens, which depended on grain imports from the Black Sea ports of Scythia, maintained critical alliances with cities which controlled the straits, such as the Megarian colony Byzantium.

Persian King Darius I the Great (r. 522 BC – 486 BC), in an attempt to subdue the Scythian horsemen who roamed across the north of the Black Sea, crossed the Bosporus, then marched towards the River Danube. His army crossed the Bosporus using an enormous bridge made by connecting Achaemenid boats.[15][16] This bridge essentially connected the farthest geographic tip of Asia to Europe, encompassing at least some 1,000 metres of open water if not more.[17] Years later, Xerxes I would construct a similar boat bridge on the Dardanelles (Hellespont) strait (480 BC), during his invasion of Greece.

The Byzantines called the Bosporus "Stenon" and used the following major toponyms in the area:[18]

- on the European side:

- Bosporios Akra

- Argyropolis

- St. Mamas

- St. Phokas

- Hestiai or Michaelion

- Phoneus

- Anaplous or Sosthenion

- on the Asian side:

- Hieron tower

- Eirenaion

- Anthemiou

- Sophianai

- Bithynian Chrysopolis

The strategic significance of the strait was one of the factors in the decision of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great to found there in AD 330 his new capital, Constantinople, which became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The expressions "swim the Bosporus" and "cross the Bosporus" were and are still used to indicate religious conversion to the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Ottoman era (1453–1922)

On 29 May 1453, the then-emergent Ottoman Empire conquered the city of Constantinople following a lengthy campaign wherein the Ottomans constructed fortifications on each side of the strait, the Anadoluhisarı (1393) and the Rumelihisarı (1451), in preparation for not only the primary battle but to assert long-term control over the Bosporus and surrounding waterways. The final 53-day campaign, which resulted in Ottoman victory, constituted an important turn in world history. Together with Christopher Columbus's first voyage to the Americas in 1492, the 1453 conquest of Constantinople is commonly noted as among the events that brought an end to the Middle Ages and marked the transition to the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery.

The event also marked the end of the Byzantines—the final remnants of the Roman Empire—and the transfer of the control of the Bosporus into Ottoman hands, who made Constantinople their new capital, and from where they expanded their empire in the centuries that followed.

At its peak between the 16th and 18th centuries, the Ottoman Empire had used the strategic importance of the Bosporus to expand their regional ambitions and to wrest control of the entire Black Sea area, which they regarded as an "Ottoman lake", on which Russian warships were prohibited.[20]

Subsequently, several international treaties have governed vessels using the waters. Under the Treaty of Hünkâr İskelesi of 8 July 1833, the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits were to be closed on Russian demand to naval vessels of other powers.[21] By the terms of the London Straits Convention concluded on 13 July 1841, between the Great Powers of Europe—Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Austria and Prussia—the "ancient rule" of the Ottoman Empire was re-established by closing the Turkish Straits to any and all warships, barring those of the Sultan's allies during wartime. It thus benefited British naval power at the expense of Russian, as the latter lacked direct access for its navy to the Mediterranean.[22]

Following the First World War, the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres demilitarized the strait and made it an international territory under the control of the League of Nations.

Turkish republican era (1923–present)

This was amended under the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which restored the straits to Turkish territory—but allowed all foreign warships and commercial shipping to traverse the straits freely. Turkey eventually rejected the terms of that treaty, and subsequently Turkey remilitarised the straits area. The reversion was formalised under the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Turkish Straits of 20 July 1936. That convention, which is still in force, treats the straits as an international shipping lane save that Turkey retains the right to restrict the naval traffic of non–Black Sea states.

Turkey was neutral in the Second World War until February 1945, and the straits were closed to the warships of belligerent nations during this time, although some German auxiliary vessels were permitted to transit. In diplomatic conferences, Soviet representatives had made known their interest in Turkish concession of Soviet naval bases on the straits. This, as well as Stalin's demands for the restitution of the Turkish provinces of Kars, Artvin and Ardahan to the Soviet Union (which were lost by Turkey in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, but were regained with the Treaty of Kars in 1921), were considerations in Turkey's decision to abandon neutrality in foreign affairs. Turkey declared war against Germany in February 1945, but did not engage in offensive actions.[23][24][25]

Turkey joined NATO in 1952, thus affording its straits even more strategic importance as a commercial and military waterway.

During the early 21st century, the Turkish Straits have become particularly important for the oil industry. Russian oil, from ports such as Novorossyisk, is exported by tankers primarily to western Europe and the U.S. via the Bosporus and the Dardanelles straits. In 2011 Turkey planned a 50 km canal through Silivri as a second waterway, reducing risk in the Bosporus.[26][27]

Crossings

.jpg)

Maritime

The waters of the Bosphorus are traversed by numerous passenger and vehicular ferries daily, as well as recreational and fishing boats ranging from dinghies to yachts owned by both public and private entities.

The strait also experiences significant amounts of international commercial shipping traffic by freighters and tankers. Between its northern limits at Rumeli Feneri and Anadolu Feneri and its southern ones at Ahırkapı Feneri and Kadıköy İnciburnu Feneri, there are numerous dangerous points for large-scale maritime traffic that require sharp turns and management of visual obstructions. Famously, the stretch between Kandilli Point and Aşiyan requires a 45-degree course alteration in a location where the currents can reach 7 to 8 knots (3.6 to 4.1 m/s). To the south, at Yeniköy, the necessary course alteration is 80 degrees. Compounding these difficult changes in trajectory, the rear and forward sight lines at Kandilli and Yeniköy are also completely blocked prior to and during the course alteration, making it impossible for ships approaching from the opposite direction to see around these bends. The risks posed by geography are further multiplied by the heavy ferry traffic across the strait, linking the European and Asian sides of the city. As such, all the dangers and obstacles characteristic of narrow waterways are present and acute in this critical sea lane.

In 2011, the Turkish Government discussed creating a large-scale canal project roughly 80 kilometres (50 mi) long that runs north–south through the western edges of Istanbul Province as a second waterway between the Black Sea and the Marmara, intended to reduce risk in the Bosphorus.[26][27] This Kanal İstanbul project currently continues to be debated.[28][29][30]

Land

Two suspension bridges and a cable-stayed bridge cross the Bosphorus. The first of these, the 15th July Martyrs Bridge, is 1,074 m (3,524 ft) long and was completed in 1973. The second, named Fatih Sultan Mehmet (Bosphorus II) Bridge, is 1,090 m (3,576 ft) long, and was completed in 1988 about 5 km (3 mi) north of the first bridge. The first Bosphorus Bridge forms part of the O1 Motorway, while the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge forms part of the Trans-European Motorway. The third, Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, is 2,164 m (7,100 ft) long and was completed in 2016.[31][32] It is located near the northern end of the Bosphorus, between the villages of Garipçe on the European side and Poyrazköy on the Asian side,[33] as part of the "Northern Marmara Motorway", integrated with the existing Black Sea Coastal Highway, and allowing transit traffic to bypass city traffic.[31][32]

| Name | Opening date | Design | Total length | Width | Height | Longest span | Clearance below | Lanes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 July Martyrs Bridge | 30 October 1973 | Suspension bridge | 1,560 m (5,118 ft) | 33.4 m (110 ft) | 165 m (541 ft) | 1,074 m (3,524 ft) | 64 m (210 ft) | 6 lanes of Motorway O1 |

| Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge | 1988 | Suspension bridge | 1,510 m (4,950 ft) | 39 m (128 ft) | 105 m (344 ft) | 1,090 m (3,580 ft) | 64 m (210 ft) | 8 lanes of Motorway O2 |

| Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge | 26 August 2016 | Hybrid cable-stayed, suspension bridge | 2,164 m (7,100 ft) | 58.4 m (192 ft) | 322 m (1,056 ft) | 1,408 m (4,619 ft) | 8 lanes of Motorway O7 and 1 double-track railway |

Submarine

The Marmaray project, featuring a 13.7 km (8.5 mi) long undersea railway tunnel, opened on 29 October 2013.[34] Approximately 1,400 m (4,593 ft) of the tunnel runs under the strait, at a depth of about 55 m (180 ft).

An undersea water supply tunnel with a length of 5,551 m (18,212 ft),[35] named the Bosporus Water Tunnel, was constructed in 2012 to transfer water from the Melen Creek in Düzce Province (to the east of the Bosphorus strait, in northwestern Anatolia) to the European side of Istanbul, a distance of 185 km (115 mi).[35][36]

The Eurasia Tunnel is a 5.4 km (3.4 mi) undersea highway tunnel, crossing the Bosphorus for vehicular traffic, between Kazlıçeşme and Göztepe. Construction began in February 2011, and was opened on 20 December 2016.[37]

Up to 4 submarine fibre optics lines (MedNautilus and possibly others) approach Istanbul, coming from the Mediterranean through the Dardanelles.[38][39]

Strategic importance

The Bosphorus is the only way for Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Russia and Ukraine to reach the Mediterranean Sea and other seas. Sovereignty over the straits is also an important issue for the riparian countries besides Turkey.

Although it is only one of the natural borders separating the European and Asian mainland, the most known is the Bosphorus. Since it is a favorable region in terms of climate and geographical conditions, it has a great role in being a settlement area for ages. The city of Istanbul, divided by the Bosphorus, is one of the few intercontinental cities in the world.

Even if Turkey has no right to receive tolls from ships passing through the strait Turkey's military has broad powers in accordance with Montreux Convention. Today, the Bosphorus Command is located on the shores of the Bosphorus and the military ships connected to the Command are anchoring in the Bosphorus waters.

Located on a peninsula at the intersection of the Black Sea, the Bosphorus and the Marmara Sea, Istanbul has been one of the most protected and hardest cities for centuries.

Sightseeing

The Bosphorus has 620 waterfront houses (yalı) built during the Ottoman period along the strait's European and Asian shorelines. Ottoman palaces such as the Topkapı Palace, Dolmabahçe Palace, Yıldız Palace, Çırağan Palace, Feriye Palaces, Beylerbeyi Palace, Küçüksu Palace, Ihlamur Palace, Hatice Sultan Palace, Adile Sultan Palace and Khedive Palace are within its view. Buildings and landmarks within view include the Hagia Sophia, Hagia Irene, Sultan Ahmed Mosque, Yeni Mosque, Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque, Nusretiye Mosque, Dolmabahçe Mosque, Ortaköy Mosque, Üsküdar Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, Yeni Valide Mosque, Maiden's Tower, Galata Tower, Rumelian Castle, Anatolian Castle, Yoros Castle, Selimiye Barracks, Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, Borusan Museum of Contemporary Art, Tophane-i Amire Museum, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Galatasaray University, Boğaziçi University, Robert College, Kabataş High School, Kuleli Military High School.

Two points in Istanbul have most of the public ferries that traverse the strait: from Eminönü (ferries dock at the Boğaz İskelesi pier) on the historic peninsula of Istanbul to Anadolu Kavağı near the Black Sea, zigzagging and calling briefly multiple times at the Rumelian and Anatolian sides of the city. At central piers shorter, regular ride in one of the public ferries cross.

Private ferries operate between Üsküdar and Beşiktaş or Kabataş in the city. The few well-known geographic hazards are multiplied by ferry traffic across the strait, linking the European and Asian sides of the city, particularly for the largest ships.[8]

The catamaran seabuses offer high-speed commuter services between the European and Asian shores of the Bosphorus, but they stop at fewer ports and piers in comparison to the public ferries. Both the public ferries and the seabuses also provide commuter services between the Bosphorus and the Prince Islands in the Sea of Marmara.

There are also tourist rides available in various places along the coasts of the Bosphorus. The prices vary according to the type of the ride, and some feature loud popular music for the duration of the trip.

Architecture of Bosphorus

The architectural style of the Bosphorus began to be shaped by simple houses in the fishing villages established on the coast during the Byzantine period.

The mansions, which were placed on the shores during the Ottoman period, became one of the most outstanding examples of Bosphorus architecture and have been identified with the Bosphorus for years. The number of mansions built on the two sides of the Bosphorus for centuries and has reached today is about 360.

Today, the majority of them still preserves their old forms, are among the most expensive real estate both in Turkey and Istanbul.

Many palace buildings has also built in the Bosphorus, which was one of the most popular places of the palace people during the Ottoman period. Dolmabahçe Palace, Çırağan Palace, Beylerbeyi Sarayı, Küçüksu Kasrı, Beykoz Kasrı ve Adile Sultan Kasrı are some of most striking structures used by sultans and his relatives from time to time. Historical buildings such as Galatasaray University, Egyptian Consulate and Sakıp Sabancı Museum are among the most famous architectural examples of the Bosphorus.

In the Ottoman era there was a tradition of building mosques and pier squares as well as pier buildings in the important districts of the Bosphorus. Beşiktaş Pier, Ortaköy Square, Ortaköy Mosque, Bebek Mosque, Beylerbeyi Mosque and Şemsipaşa Mosque are some of traces from that tradition.

Image gallery

View of the European side of Istanbul from the southern entrance to the Bosphorus.

View of the European side of Istanbul from the southern entrance to the Bosphorus. View of the European side of Istanbul from the Bosphorus.

View of the European side of Istanbul from the Bosphorus. View of the entrance to the Bosphorus from the Sea of Marmara, as seen from the Topkapı Palace.

View of the entrance to the Bosphorus from the Sea of Marmara, as seen from the Topkapı Palace. Panoramic view of the Bosphorus as seen from Ulus on the European side, with the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge (1988) at left and the Bosphorus Bridge (1973) at right.

Panoramic view of the Bosphorus as seen from Ulus on the European side, with the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge (1988) at left and the Bosphorus Bridge (1973) at right. Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge (1988) and the Bosphorus strait.

Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge (1988) and the Bosphorus strait. Dolmabahçe Palace on the Bosphorus.

Dolmabahçe Palace on the Bosphorus. View from Topkapi Palace on the Bosphorus.

View from Topkapi Palace on the Bosphorus. View of the Bosphorus from the Marmara Hotel, Taksim Square.

View of the Bosphorus from the Marmara Hotel, Taksim Square. The Rumelian Castle on the Bosphorus, with both suspension bridges which span the strait.

The Rumelian Castle on the Bosphorus, with both suspension bridges which span the strait._on_the_Bosphorus%2C_Turkey_001.jpg) 620 historic waterfront houses stretch along the coasts of the Bosphorus, such as the yalı of Ahmet Rasim Pasha.

620 historic waterfront houses stretch along the coasts of the Bosphorus, such as the yalı of Ahmet Rasim Pasha. Yalı of Hacı Şefik Bey on the Bosphorus.

Yalı of Hacı Şefik Bey on the Bosphorus. Ottoman era waterfront houses on the Bosphorus.

Ottoman era waterfront houses on the Bosphorus. Afif Pasha Mansion on the Bosphorus was designed by Alexander Vallaury.

Afif Pasha Mansion on the Bosphorus was designed by Alexander Vallaury. The quarters of Bebek, Arnavutköy and Yeniköy on the Bosphorus are famous for their fish restaurants.

The quarters of Bebek, Arnavutköy and Yeniköy on the Bosphorus are famous for their fish restaurants. Ottoman era waterfront houses (yalı) on the Bosphorus.

Ottoman era waterfront houses (yalı) on the Bosphorus. Ottoman era waterfront houses (yalı) on the Bosphorus.

Ottoman era waterfront houses (yalı) on the Bosphorus. Ottoman era waterfront houses (yalı) on the Bosphorus.

Ottoman era waterfront houses (yalı) on the Bosphorus.- Boat on Bosphorus as seen from Sultanahmet street.

A view of the Bosporus strait, with the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge visible in the background.

A view of the Bosporus strait, with the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge visible in the background. A cruise ship (left) and Seabus (right) navigating through the Bosporus, with the Dolmabahçe Palace visible at the right end of the frame.

A cruise ship (left) and Seabus (right) navigating through the Bosporus, with the Dolmabahçe Palace visible at the right end of the frame. Skyline of Levent as seen from the Khedive Palace gardens on the Asian coast of the Bosporus. Istanbul Sapphire is the first skyscraper at right.

Skyline of Levent as seen from the Khedive Palace gardens on the Asian coast of the Bosporus. Istanbul Sapphire is the first skyscraper at right.

See also

- Great Istanbul Tunnel, a proposed three-level road-rail undersea tunnel

- Istanbul Canal

- List of maritime incidents in the Turkish Straits

- Public transport in Istanbul

- Rail transport in Turkey

Notes

- The spelling Bosporus is listed first or exclusively in all major British and American dictionaries (e.g. Oxford Online Dictionaries, Collins, Longman, Merriam-Webster, American Heritage, and Random House) as well as the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Columbia Encyclopedia. The American Heritage Dictionary's online version has only this spelling and its search function does not even find anything for the spelling Bosphorus. The Columbia Encyclopedia specifies that the pronunciation of the alternative spelling ph is also /p/, but dictionaries also list the pronunciation /f/.

- There is a certain (Oxonian) tradition of equating the name "Oxford" with "Bosporus", see e.g. Wolstenholme Parr, Memoir on the propriety of the word Oxford, Oxford,1820, esp. p. 18

- Entry: Βόσπορος at Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, 1940, A Greek–English Lexicon.

- F. Sickler (1824). Handbuch der alten Geographie (in German). Bonné. p. 551.

Die ihr entgegenstehende Landspitze hieß auch Bous oder Damalis, mit einer ehernen coloss. Bildsäule einer Kuh; aber hier war es auch, wo der Athen. Chares seiner Frau, der Damalis, ein Grabmal errichten ließ so dass die größere Wahrscheinlichkeit dafür ist, daß wenigstens diese Landspitze eher von der Frau Damalis als von der Prinzessin Jo ihren Namen erhalten habe.

- Bosporus in Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary (1879).

- Carl Müller (1861). Geographi graeci minores (in Latin). Didot. p. 7.

Herodotus (4, 85) nominat Bosporum Calchedoniæ (τῆς Καλχηδονίς τὸν Βόσπορον); Strabo, os Byzantiacum (p. 125 στόμα Βυζαντιακόν, p. 318 στόμα τὸ κατὰ Βυζάντιον); Joannes Tzetzes (Chil. 1, 886) appellat Bosporum Damaliten (τὸν Δαμαλίτην Βόσπορον) sua ætate nuncupatum vulgo Prosphorium.

- Friedrich Heinrich Theodor Bischoff (1829). Verleichendes wörterbuch der alten, mittleren und neuen geographie (in German). Becker. pp. 195f.

- "Türk Boğazları ve Marmara Denizi'nin Coğrafi Konumu-İstanbul Boğazı" (in Turkish). Denizcilik. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- Gregg, M. C., and E. O¨ zsoy (2002), Flow, water mass changes, and hydraulics in the Bosphorus, J. Geophys. Res., 107(C3), 3016, doi:10.1029/2000JC000485

- "Leeds Researchers Study Undersea Rivers with a Yellow Submarine". University of Leeds. 2 August 2010. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Robotic sub records flow of undersea river – Futurity". 2 August 2010.

- Di Iorio, D., and Yüce, H. (1999). "Observations of Mediterranean flow into the Black Sea". Journal of Geophysical Research 104(C2), 3091–3108.

- Lericolais, G., Le Drezen, E., Nouzé, H., Gillet, H., Ergun, M., Cifci, G., Avci, M., Dondurur, D., and Okay, S. (2002). "Recent canyon heads evidenced at the Bosporus outlet". EOS transactions, AGU Fall Meet. Suppl. 83(47), Abstract PP71B-0409.

- Flood, R. D., Hiscott, R. N., and Aksu, A. E. (2009). "Morphology and evolution of an anastomosed channel network where saline underflow enters the Black Sea". Sedimentology 56(3), 807–839.

- Polybius, Historiae IV, 39, 16;

- Özhan Öztürk (2011). PONTUS: Antikçağ'dan Günümüze Karadeniz'in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi. Archived at the Wayback Machine. Ankara. pp. 28–29. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15.

- Herodotus (1859). The History of Herodotus: a new English version, Volume 3. Translated by George Rawlinson; Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson; Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. John Murray. pp. 77 (Chp. 86).

bosphorus width.

- Özhan Öztürk. Pontus: Antik Çağ'dan Günümüze Karadeniz'in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi Genesis Yayınları Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine. Ankara, 2011 pp. 28–32.

- http://m.vam.ac.uk/collections/item/O136489/the-bosphorus-with-the-castles-watercolour-thomas-allom/

- "Turkey – Köprülü Era". Workmall.com. 2007-03-24. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- "Turkey – External Threats and Internal Transformations". Workmall.com. 2007-03-24. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- Christos L. Rozakis (1987). The Turkish Straits. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9024734649.

- "Foreign Policy Research Institute: The Turkish Factor in the Geopolitics of the Post-Soviet Space (Igor Torbakov)". Fpri.org. 2003-01-10. Archived from the original on 2010-07-31. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- "Turkish-Soviet Relations". Robert Cutler. 1999-03-28. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- "Today's Zaman: Against who and where are we going to stand? (Ali Bulaç)". Todayszaman.com. Archived from the original on 2009-05-04. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- "Turkey to build Bosphorus bypass" New Civil Engineer, 20 April 2011. Accessed: 2 December 2014.

- Marfeldt, Birgitte. "Startskud for gigantisk kanal gennem Tyrkiet" Ingeniøren, 29 April 2011. Accessed: 2 December 2014.

- "İstanbul Canal project to open debate on Montreux Convention". Today's Zaman. 2010-10-08. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30.

- "Turkey debates whether international treaty is obstacle to plan to bypass the Bosporus". The Washington Post. 2011-04-29.

- "Turkey's Ambitious Canal Proposal". STRATFOR. May 16, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

Registry required.

- "3rd Bosphorus bridge opening ceremony". TRT World. 25 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016.

- "Istanbul's mega project Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge to open in large ceremony".

- "Turkey Unveils Route for Istanbul's Third Bridge". Anatolian Agency. 29 April 2010. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010.

- "Turkey's Bosporus tunnel to open sub-sea Asia link". BBC News. 29 October 2013.

- "Melen hattı Boğaz'ı geçti".

- Nayır, Mehmet (2012-05-19). "Melen Boğaz'ı geçiyor". Sabah Ekonomi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- "Eurasia Tunnel Project" (PDF). Unicredit - Yapı Merkezi, SK EC Joint Venture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- Gülnazi Yüce: Submarine Cable Projects (2-03) presented at First South East European Regional CIGRÉ Conference (SEERC), Portoroz, Slovenis, 7–8 June 2016, retrieved 8 April 2018. – PDF

- Submarine Cable Map 2017 telegeography.com, retrieved 9 April 2018.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Istanbul/Bosphorus. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bosporus. |