Duchy of Berg

Berg was a state—originally a county, later a duchy—in the Rhineland of Germany. Its capital was Düsseldorf. It existed as a distinct political entity from the early 12th to the 19th centuries.

County (Duchy) of Berg | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1101–1815 | |||||||||

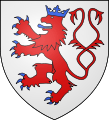

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

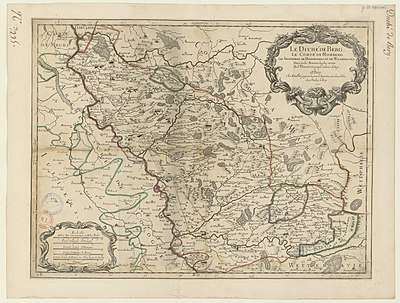

.svg.png) Map of the Lower Rhenish–Westphalian Circle around 1560, Duchy of Berg highlighted in red | |||||||||

| Status | Duchy | ||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||

| Common languages | German | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Emergence from Lotharingia | 1101 | ||||||||

• Split with County of Mark | 1160 | ||||||||

• United with County of Jülich | 1348 | ||||||||

| 1521 | |||||||||

• United with Palatinate-Neuburg and the Electorate of the Palatinate | 1609 and 1690 | ||||||||

• Awarded to Prussia | 9 June 1815 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

History

Ascent

The Counts of Berg emerged in 1101 as a junior line of the dynasty of the Ezzonen, which traced its roots back to the 9th-century Kingdom of Lotharingia, and in the 11th century became the most powerful dynasty in the region of the lower Rhine.

In 1160, the territory split into two portions, one of them later becoming the County of the Mark, which returned to the possession of the family line in the 16th century. In 1280 the counts moved their court from Schloss Burg on the Wupper river to the town of Düsseldorf. The most powerful of the early rulers of Berg, Engelbert II of Berg died in an assassination on November 7, 1225.[1][2] Count Adolf VIII of Berg fought on the winning side in the Battle of Worringen against Guelders in 1288.

The power of Berg grew further in the 14th century. The County of Jülich united with the County of Berg in 1348,[3] and in 1380 the Emperor Wenceslaus elevated the counts of Berg to the rank of dukes, thus originating the Duchy of Jülich-Berg.

Problems of succession

.png)

In 1509, John III, Duke of Cleves, made a strategic marriage to Maria von Geldern, daughter of William IV, Duke of Jülich-Berg, who became heiress to her father's estates: Jülich, Berg and the County of Ravensberg, which under the Salic laws of the Holy Roman Empire caused the properties to pass to the husband of the female heir (women could not hold property except through a husband or a guardian). With the death of her father in 1521 the Dukes of Jülich-Berg became extinct, and the estate thus came under the rule of John III, Duke of Cleves — along with his personal territories, the County of the Mark and the Duchy of Cleves (Kleve) in a personal union. As a result of this union the dukes of the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg controlled much of present-day North Rhine-Westphalia, with the exception of the clerical states of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the Bishop of Münster.

However, the new ducal dynasty also became extinct in 1609, when the last duke died insane. This led to a lengthy dispute over succession to the various territories before the partition of 1614: the Count Palatine of Neuburg, who had converted to Catholicism, annexed Jülich and Berg; while Cleves and Mark fell to John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, who subsequently also became Duke of Prussia. Upon the extinction of the senior dynasty ruling the Electorate of the Palatinate in 1685, the Neuburg line inherited the Electorate and generally made Düsseldorf its capital until the Elector Palatine also inherited the Electorate of Bavaria in 1777.

French revolution, Grand Duchy of Berg

The French occupation (1794–1801) and annexation (1801) of Jülich (French: Juliers) during the French revolutionary wars separated the two duchies of Jülich and Berg, and in 1803 Berg separated from the other Bavarian territories and came under the rule of a junior branch of the Wittelsbachs. In 1806, in the reorganization of the German lands occasioned by the end of the Holy Roman Empire, Berg became the Grand Duchy of Berg, under the rule of Napoleon's brother-in-law, Joachim Murat.[4] Murat's arms combined the red lion of Berg with the arms of the duchy of Cleves. The anchor and the batons came to the party due to Murat's positions as Grand Admiral and as Marshal of the Empire. As the husband of Napoleon's sister Caroline Bonaparte, Murat also had the right to use the imperial eagle.

In 1809, one year after Murat's promotion from Grand Duke of Berg to King of Naples, Napoleon's young nephew, Prince Napoleon Louis Bonaparte (1804–1831, elder son of Napoleon's brother Louis Bonaparte, King of Holland) became the Grand Duke of Berg; French bureaucrats administered the territory in the name of the child. The Grand Duchy's short existence came to an end with Napoleon's defeat in 1813 and the peace settlements that followed.

Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

In 1815, after the Congress of Vienna, Berg became part of a province of the Kingdom of Prussia: the Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. In 1822 this province united with the Grand Duchy of the Lower Rhine to form the Rhine Province.

Rulers of Berg

.svg.png)

House of Ezzonen

- Hermann I "Pusillus", Count Palatine of Lotharingia

- Adolf I of Lotharingia, Vogt of Deutz

- Adolf II of Lotharingia, Vogt of Deutz

House of Berge

- 1077–1082 Adolf I of Berg, 1st Count of Berg

- 1082–1093 Adolf II of Berg-Hövel (Huvili), Count of Berg

- 1093–1132 Adolf III, Count of Berg

- 1132–1160 Adolf IV, Count of Berg

- c.1140-1148 Adolf V, Count of Berg

- 1160–1189 Engelbert I, Count of Berg

- 1189–1218 Adolf VI, Count of Berg

- 1218–1225 Engelbert II of Berg, Archbishop of Cologne, Regent of Berg

- 1218–1248 Irmgard, heiress of Berg, marries in 1217 Henry IV, Duke of Limburg

House of Limburg

- 1218–1247 Henry IV Duke of Limburg, Count of Berg

- 1247–1259 Adolf VII Count of Limburg, Count of Berg

- 1259–1296 Adolf VIII

- 1296–1308 William I

- 1308–1348 Adolf IX

House of Jülich(-Heimbach), Counts

– in union with Ravensberg –

- 1348–1360 Gerhard

- 1360–1380 Wilhelm II; became duke in 1380

House of Jülich(-Heimbach), Dukes

– in union with Ravensberg (except 1404–1437) and after 1423 in union with the duchy of Jülich –

- 1380–1408 William I

- 1408–1437 Adolf

- 1437–1475 Gerhard

- 1475–1511 Wilhelm II

House of La Marck, Dukes

– from 1521 a part of the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg–

- 1511–1539 Johann

- 1539–1592 William III

- 1592–1609 Johann Wilhelm I

House of Wittelsbach, Dukes

– in union with Jülich und Palatinate-Neuburg, from 1690 also with the Electorate of the Palatinate, from 1777 also with Bavaria–

- 1614–1653 Wolfgang Wilhelm

- 1653–1679 Phillip Wilhelm

- 1679–1716 Johann Wilhelm II

- 1716–1742 Karl Phillip

- 1742–1799 Karl Theodor

- 1799–1806 Maximilian Josef

- 1803–1806 William of Palatinate-Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld-Gelnhausen, Duke in Bavaria (administrator)

French Grand Dukes

.svg.png)

- 1806–1808 Joachim Murat

- 1808–1809 Napoléon Bonaparte[5]

- 1809–1813 Napoleon Louis Bonaparte (under the regency of Napoléon Bonaparte)

Coat of arms

The historic coat of arms of Berg shows a red lion with a double tail and blue crown, tongue, and claws – blazoned as: Argent a lion rampant gules, queue fourchée crossed in saltire, armed, langued, and crowned azure. This lion originates from the arms of the Duke of Limburg as the Berg title in the 13th century fell to the Limburg line.

Heraldic shield of arms

Heraldic shield of arms

See also

References

- Pixton, Paul B. (1995). The German episcopacy and the implementation of the decrees of the Fourth Lateran Council : 1216–1245 : watchmen on the tower. Leiden u.a.: Brill. p. 210. ISBN 978-9004102620.

- Butler, Alban; Burns, Paul (2000). Butler's Lives of the Saints (New full ed.). Collegeville (Minn.): Liturgical Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0814623879.

- Knight, Charles (2012). The English Cyclopaedia: Geography. Lightning Source UK Ltd. p. 1030. ISBN 978-1277123517.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: or, A dictionary of arts, sciences, and miscellaneous literature, enlarged and improved, Volume 3. Google e-books. p. 570.

- Napoleon’s decree in his quality of Grand Duke of Berg in Intelligenz-Nachrichten, June 24, 1809 (Stück XXV), pp. 341–342. Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum.

External links

- Lwl.org: Edicts of Jülich, Cleves, Berg, Grand Duchy Berg, 1475–1815 (Coll. Scotti)

- Hoeckmann.de: Historical Map of Northrhine-Westphalia in 1789