Belchertown State School

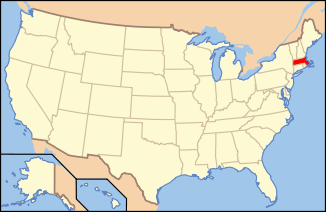

The Belchertown State School for the Feeble-Minded was established in 1922 in Belchertown, Massachusetts. It became known for inhumane conditions and poor treatment of its patients, and became the target of a series of lawsuits prior to its eventual closing in 1992. The building complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

| Belchertown State School | |

|---|---|

| Massachusetts Department of Public Health | |

| |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Belchertown, Massachusetts, Massachusetts, United States |

| Coordinates | 42°16′29.84″N 72°24′54.41″W |

| Organization | |

| Type | Psych |

| Services | |

| History | |

| Opened | 1922 |

| Closed | December 31, 1992 |

Belchertown State School | |

| |

| Location | Belchertown, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Built | 1915 |

| Architect | Kendall, Taylor & Co. |

| Architectural style | Bungalow/Craftsman, Colonial Revival, Italianate |

| MPS | Massachusetts State Hospitals And State Schools MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 94000688 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 19, 1994 |

Conditions and treatment of patients

Located at 30 State Street, the 876-acre (3.55 km2) campus contains 10 major buildings built in a Colonial Revival style by Kendall, Taylor, and Co. The state schools of Massachusetts were different from state hospitals; the latter were for the mentally ill, while state schools were institutions for the mentally defective (the name is a misnomer, as they did not generally involve any form of education).

Throughout its first 40 years, Belchertown operated mostly without scrutiny from outside sources. Author Benjamin Ricci (whose son lived at the school, and who later led a class-action lawsuit protesting the conditions there) referred to the conditions as "horrific," "medieval,"[2] and "barbaric."[3] Doctors at the school had little regard for patients' mental capacity, evidenced by this quote:

His method of evaluating me consisted of looking me over during the physical exam and deciding that since I couldn't talk and apparently couldn't understand what he was saying, I must be an imbecile. [...] Since I couldn't ask him to speak up or repeat what he said, he assumed I was a moron. (Sienkewicz-Mercer p38)

Attendants on the wards were overworked, with dozens of patients in each ward. Because there was not enough time for proper toilet care, residents were left "half-naked rolling in their own excrement."[4] Healthy teeth were often removed from handicapped patients to make feeding them easier.

Those who were severely physically handicapped were left in their beds the entire day, without any form of entertainment. Patients unable to feed themselves were force-fed by the attendants (Sienkewicz-Mercer, p. 42); when it was necessary to move a patient, the attendants did so roughly, sometimes causing injuries.[4] As a result of this gross mistreatment, some patients were prone to "moaning in the hallways," "reaching into [their] diapers and spreading whatever [they] found all over, [...] repeatedly banging their heads against the walls," (Sienkewicz-Mercer, p. 50) or any of a number of other responses. Additionally, the facility suffered from vermin infestation.

Changing attitudes towards mental retardation

The reason for this situation was partly due to the prevailing cultural perspective of what was often called "mental deficiency". Around the turn of the 20th century, many people with handicaps were simply kept at home when possible. This changed in the 1920s and 1930s because state governments and bureaucracies developed special divisions to manage these individuals—in Massachusetts and elsewhere, this was the role of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Retardation. In addition, expertise on "the infirm" became a specialty in the medical world, which in turn helped shape social policy. And while few parents would want to send their child to live in squalor and suffer abuse, many felt they had no other choice as there was simply nowhere else for a child with severe disabilities to go. Doctors at the time would often tell them that this was the only way for their other children to have a normal childhood.

Beginning in the Kennedy administration, and partly due to the civil rights movement started by African Americans, awareness of disabled people as individuals with human rights increased. In 1966, Massachusetts passed the Mental Health and Retardation Services Act, which mandated a gradual transition from a few institutions around the state to a more community-based system of care facilities. Coincidentally, a conscientious objector to the Vietnam war was arranging for a group of six mobility impaired, non-retarded to move into "Prospect House" in Cambridge, Mass. These men would still commute to their highly paid day jobs at the tool and die factory abutting Fernald; but with the alliance with the Cambridge-Somerville Assn. for Retarded Children (as it was then known), efforts to socialize these men into community living were undertaken.

This enabled Fernald to join Brandeis' Florence Heller School in undertaking the creation of a community residential program. Working to create partnerships with Associations for Retarded Citizens, mobilizing staff on the units, and working with the families of residents to educate them on the concepts of normalization, these efforts were rewarded with the opening of a community residence for eight moderately retarded women on Morse St., in Watertown, MA in 1970. From this beginning, state-private collaboration expanded and community residential and support programs began to flourish.[citations needed]

The horrendous conditions at Belchertown were revealed in 1971 in a newspaper article entitled "The Tragedy of Belchertown". Parents sued the school, and when the state Attorney General toured the facility, he described it as "a hell hole".

This was the first lawsuit against a state school, and others followed in Massachusetts for the next few years.[5] In 1973, the unnecessary death of a patient resulted in a lawsuit that saw the hiring of nearly 100 new ward personnel. In 1975, Belchertown was sued once again for denying its patients the right to vote (this was one of the first disability-related voting rights cases in the United States), and in 1977 a case was brought against the school on behalf of a 67-year-old mentally ill man unable to properly take care of himself with leukemia to determine if a court-appointed guardian ad litem could refuse treatment on his behalf.[6][7]

School closure and redevelopment

After hobbling along for several more years, Belchertown State Schools were finally closed in 1992. Two years later it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[8] More recent improvements have been the makeover of Foley Field into a baseball diamond for the local Little League team,[9] and restoration of the overgrown cemetery (with numbers marking the graves) to appear cleaner and properly memorialize dead patients by name.[10] In 2001, a town meeting designated the school property as an Economic Opportunity Area for 20 years. This economic development plan provides tax incentives to businesses who establish themselves on the site.

As of November 14, 2012, the town of Belchertown had decided on a $1.25 million project, that would hand over the ownership of the land to a new owner. The new owners plan was to demolish the existing buildings which contained asbestos. The plan was to replace them with a new facility of 170-units of assisted living homes. The project was due to be completed by Winter of 2014 but development fell under and the land owner backed out. The buildings had been boarded up and road blocks were placed, but they have remained untouched.[11][12] Plans to demolish the buildings started up again in November 2014, with the same idea to create an assisted-living facility.

By July 2016, two of the most notable buildings were demolished, the Hospital and the iconic Auditorium buildings.

From 2015 onward, the campus underwent multiple arson attempts by vandals.[13][14] The public outcry led to a significantly higher police presence[15] and arrests that followed.

For more information about Belchertown, there is a book entitled Crimes Against Humanity: A Historical Perspective. It was written by Benjamin Ricci, who sent his six-year-old son Bobby to live there not knowing what the conditions were like, and who was involved in the initial 1972 lawsuit. Another book with vivid descriptions of Belchertown is Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer's I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes; she was a resident of the school in the 1960s and 1970s. Sienkiewicz-Mercer's book refers to a young male nurse who worked at Belchertown in the late 1960s and early 1970s who later became a junior senator from Massachusetts. His name, she says, was John Kerry.[16] This is a disputable statement, since Senator Kerry graduated from Yale in 1966 and served in the U.S. Navy from 1966 to 1970.

Buildings

Ground was broken at the Belchertown State School in March 1919.[17] Construction was completed in 1922 with subsequent additions thereafter.

- Administrative Block - two buildings connected by a corridor. Most known for its small white clock tower. Used for administrators only.

- Cottages - nine white houses where more capable patients resided. Caretakers are asked in 1972 to vacate to make room for excess patients.[17] All demolished by 2017.

- Hospital - held approximately 50 beds for children with disabilities. The building was demolished in 2015 for redevelopment.

- Infirmary - a ward where more-seriously disabled residents resided, which was demolished in 2016.

- Auditorium/Gymnasium - one of the most infamous buildings at BSS. Below ground contained a gym. Demolished in 2015 after PCB concerns.

- Vocational Block - a building where female patients could partake in activities such as coloring, painting, and knitting. Demolished in 2015.

- Industrial Block - a building where male patients could learn carpentry, basketball, and other "male" tasks. Demolished in 2015.

- A & K Wards - custodial buildings that housed male and female patients respectively. Demolished in 1977 and 1979, they symbolic acts of progress.[17]

- G Ward - the campus's newest building. Built in 1964, it was considered inadequate for the facility's residents due to its large windows and location. Demolished in 2017.

- Custodials - wards that were nicknamed after their "+, or plus" shaped layout. The Belchertown campus was littered with these custodials.

- Kitchen Block - a building where residents could receive meals. Sewage often spewed out of the drains and onto the kitchen and dining hall floors.

- Cannery - where unused food was canned and preserved for future use.

- Drying Ground - resident laundry was processed here. Like many other state schools, residents often never ended up wearing the same clothes after laundry as it was often lost.

- Maintenance - includes a garage, loading dock, and shed for the general upkeep of the facility.

- Power Station - generated steam power for the facility until the complex switched to supplied power by a third-party sometime in the 1970s. The building was still used as a warehouse.

- Numerous fallout shelters are located within the forest surrounding the Belchertown State School campus.

Collaboration with University of Massachusetts students

In late 2008, Belchertown State School campus was the focus of an interdisciplinary studio done by 30 graduate students within the Departments of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Four teams of landscape architects, architects and regional planners studied the campus, the town, and its surrounding context. The focus of the studio was to get down to the site planning level dealing with the integration of interior and exterior spaces. The 155-acre (0.63 km2) parcel of land, owned by the Belchertown Economic Development and Industrial Corporation, is ripe with opportunity. The teams looked at creating jobs, mixed use development as well as recreational opportunities on the campus and the adjacent property, owned by New England Small Farm Institute.

The site has dozens of buildings that are beyond repair, but the majority of the substantial buildings on site would provide a strong starting point to build a community around. Landscape architect and architect students worked to integrate these buildings and the landscape together, while the regional planners looked at the feasibility of the proposals as well as zoning regulations and potential overlays. The final product was four detailed master plans and a strong sense of support from the community.

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- Archived March 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "Commonwealth of Massachusetts Statewide Independent Living Council (MASILC)". Retrieved March 18, 2005.

- "MetroWest Daily News". Retrieved March 18, 2005.

- "Psychiatry and the Law". Bama.ua.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- "Committee for Public Counsel Services :: Index". Mass.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- "National Register of Historical Places - MASSACHUSETTS (MA), Hampshire County". Nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- "Belchertown Little League". Eteamz.active.com. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- "Getting Started dsmc". Dsmc.info. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- Archived June 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Michael Seward (August 1, 2013). "Belchertown State School site redevelopment highlights the importance of due diligence when buying or selling real estate". Sawicki Real Estate. Archived from the original on 2014-05-19. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- "Fire at old Belchertown State School destroys building, considered suspicious". masslive.com. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- "Arson suspected in Belchertown State School fire". masslive.com. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- "Police raise trespassing enforcement at former Belchertown State School; site's 'folklore' attracts people 'from all over'". masslive.com. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- Sienkiewicz-Mercer, Ruth; Kaplan, Steven B. (1996). I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes (Whole Health Books rev. ed.). West Hartford, Conn.: Whole Health Books. p. 230. ISBN 0-9644616-3-3.

- "Belchertown State School Timeline" (PDF). TheAdvocacyNetwork. October 17, 2017.

External links

- Sienkiewicz-Mercer, Ruth, and Steven B. Kaplan. I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes. Whole Health Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0-9644616-3-5

- 1856.org

- Advocates seek DOJ review of Texas Youth Comm. Facilities - WebGUI

- Hampshire County, Massachusetts 1930 (T626-912) Team Census Transcription

- Matsuishi-lab.org

- A collection of photographs

- Additional photographs from an artistic view

- A history of the school