Battle of Minden

The Battle of Minden was a major engagement during the Seven Years' War, fought on 1 August 1759. An Anglo-German army under the overall command of Field Marshal Ferdinand of Brunswick defeated a French army commanded by Marshal of France, Marquis de Contades. Two years previously, the French had launched a successful invasion of Hanover and attempted to impose an unpopular treaty of peace upon the allied nations of Britain, Hanover and Prussia. After a Prussian victory at Rossbach, and under pressure from Frederick the Great and William Pitt, King George II disavowed the treaty. In 1758, the allies launched a counter-offensive against the French forces and drove them back across the Rhine.

After the allies failed to defeat the French before reinforcements swelled their retreating army, the French launched a fresh offensive, capturing the fortress of Minden on 10 July. Believing Ferdinand's forces to be over-extended, Contades abandoned his strong positions around the Weser and advanced to meet the Allied forces in battle. The decisive action of the battle came when six regiments of British and two of Hanoverian infantry, in line formation, repelled repeated French cavalry attacks; contrary to all fears that the regiments would be broken. The Allied line advanced in the wake of the failed cavalry attack, sending the French army reeling from the field, ending all French designs upon Hanover for the remainder of the year.

In Britain, the victory is celebrated as contributing to the Annus Mirabilis of 1759.

Background

The western German-speaking states of Europe had been a major theatre of the Seven Years' War since 1757, when the French had launched an invasion of Hanover. This culminated in a significant victory for the French at the Battle of Hastenbeck and the attempted imposition of the Convention of Klosterzeven upon the defeated allies: Hanover, Prussia and Britain.[3] Prussia and Britain refused to ratify the convention and, in 1758, a counter-offensive commanded by Ferdinand saw French forces first driven back across the Rhine, and then beaten at the Battle of Krefeld. The Prussian port of Emden was also recaptured, securing supply from Britain. In fact, the British government, which had previously been opposed to any direct involvement on the continent, took the opportunity of the 1758–59 winter break in fighting to send nine thousand British troops to reinforce Ferdinand.[4] The French crown also sent a reinforcing army, under Contades, hoping this would help to secure a decisive victory, swiftly concluding the costly war, and forcing the Allies to accept the peace terms France was seeking.

In an attempt to defeat the French before their reinforcements arrived, Ferdinand decided to launch a fresh counter-offensive, and quit his winter quarters early. In April, however, Victor-François, Duke de Broglie and the French withstood Ferdinand's attack at the Battle of Bergen, and de Broglie was promoted to Marshal of France. Ferdinand was forced to retreat northwards in the face of the now reinforced French army. Contades, senior of the two French marshals, resumed the advance, occupying a number of towns and cities including the strategic fortress at Minden, which fell to the French on 10 July.[5] Ferdinand was criticised for his failure to check the French offensive. His celebrated brother-in-law, Frederick the Great, is reported as having suggested that, since his loss at Bergen, Ferdinand had come to believe the French to be invincible.[6] Irrespective of any presumed crisis of confidence, however, Ferdinand did ultimately decide to confront the French, near Minden.

Contades had taken up a strong defensive position along the Weser around Minden, where he had paused to regroup before he continued his advance. He initially resisted the opportunity to abandon this strong position to attack Ferdinand. Ferdinand instead formulated a plan that involved splitting his force into several groups to threaten Contades' lines of supply. Perceiving Ferdinand's forces to be over-extended, Contades thought he saw a chance for the desired decisive victory. He ordered his men to abandon their defensive encampments and advance into positions on the plain west of Minden during the night of 31 July and early morning of 1 August.[7]

Topography

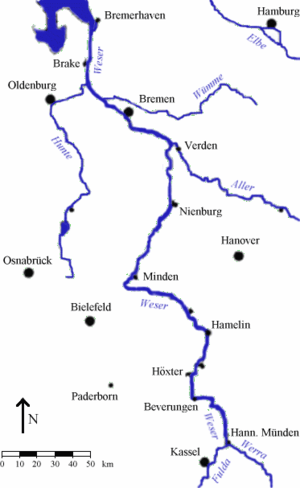

In 1759, the fortified city of Minden, now the Innenstadt (inner city) of modern Minden, was situated at the confluence of the Weser, which flows from south to north, and the Bastau, a marshy tributary rivulette. The Bastau drains into the Weser from west to east, roughly parallel with, and south of, the western arm of modern Germany's Midland Canal, where it crosses the Weser at Minden, north of the Innenstadt via the second largest water bridge in Europe). The Battle of Minden took place on the plain immediately in front of the city and its fortifications, to its northwest, with the Weser and Bastau lying behind the city to its east and south respectively.

On the 31st, the French troops under Contades' direct command had their positions west of the Weser and south of the Bastau, crossing to the north over five pontoons during the night and early morning of the 1st. The French under the junior marshal, de Broglie, were stationed astride the Weser. Some were occupying Minden on the 31st, while the remainder, stationed east of the Weser, crossed over to join them during the night.

Battle

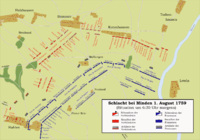

In an exception to the norm for the era, Contades placed his artillery in the centre protected only by the cavalry, with his infantry on each flank. The battle began on the French right flank, where Marshal de Broglie, who commanded the reserve, began an artillery duel against the allied left.

The decisive action of the battle took place in the centre, famously due to a misunderstanding of orders. Friedrich von Spörcken's division, composed of the infantry of the British contingent of the allied army (two brigades under Earl Waldegrave and William Kingsley) and supported by the Hanoverian Guards, actually advanced to attack the French cavalry. It is reported that they had been ordered "to advance [up-]on the beating of drums" (i.e., advance when the signal drums begin to beat,) misunderstanding this as "to advance to the beating of drums" (i.e., advance immediately while beating drums.) Since the French cavalry was still in its ranks and the famous 'hollow square' had not yet been developed, it was assumed by all that the six leading British regiments were doomed. Despite being under constant artillery fire, the six regiments (soon supported by two Hanoverian battalions), by maintaining fierce discipline and closed ranks, drove off repeated cavalry charges with musket fire and inflicted serious casualties on the French. Contades reportedly said bitterly, "I have seen what I never thought to be possible—a single line of infantry break through three lines of cavalry, ranked in order of battle, and tumble them to ruin!"[8]

Supported by the well-served British and Hanoverian artillery, the entire allied line eventually advanced against the French army and sent it fleeing from the field. The only French troops capable of mounting any significant resistance were those of de Broglie, who formed a fighting rear guard.

The following is an account of the battle by Lt. Hugh Montgomery of the 12th Regiment of Foot, to his mother:

1 August 1759

Dear madam - The pursuit of the enemy, who have retired with the greatest precipitation, prevents me from giving you so exact an account of the late most glorious victory over the French army as I would, had I almost any leisure, however here goes as much as I can.

We marched from camp between 4 and 5 o'clock in the morning, about seven drew up in a valley, from thence marched about three hundred yards, when an eighteen pound ball came gently rolling up to us. Now began the most disagreeable march that I ever had in my life, for we advanced more than a quarter of a mile through a most furious fire from a most infernal battery of eighteen-pounders, which was at first upon our front, but as we proceeded, bore upon our flank, and at last upon our rear. It might be imagined, that this cannonade would render the regiments incapable of bearing the shock of unhurt troops drawn up long before on ground of their own choosing, but firmness and resolution will surmount almost any difficulty. When we got within about 100 yards of the enemy, a large body of French cavalry galloped boldly down upon us; these our men by reserving their fire until they came within thirty yards, immediately ruined, but not without receiving some injury from them, for they rode down two companies on the right of our regiment, wounded three officers, took one of them prisoner with our artillery Lieutenant, and whipped off the Tumbrells. This cost them dear for it forced many of them into our rear, on whom the men faced about and five of them did not return. These visitants being thus dismissed, without giving us a moment's time to recover the unavoidable disorder, down came upon us like lightning the glory of France in the persons of the Gens d'Armes. These we almost immediately dispersed without receiving hardly any mischief from the harmless creatures. We now discovered a large body of infantry consisting of seventeen regiments moving down directly on our flank in column, a very ugly situation; but Stewart's Regiment and ours wheeled, and showed them a front, which is a thing not to be expected from troops already twice attacked, but this must be placed to the credit of General Waldgravie and his aide-de-camp. We engaged this corps for about ten minutes, killed them a good many, and as the song says, 'the rest then ran away'.

The next who made their appearance were some Regiments of the Grenadiers of France, as fine and terrible looking fellows as I ever saw. They stood us a tug, notwithstanding we beat them off to a distance, where they galded us much, they having rifled barrels, and our muskets would not reach them. To remedy this we advanced, they took the hint, and ran away. Now we were in hopes that we had done enough for one day's work, and that they would not disturb us more, but soon after a very large body of fresh infantry, the last resource of Contades, made the final attempt on us. With them we had a long but not very brisk engagement, at last made them retire almost out of reach, when the three English regiments of the rear line came up, and gave them one fire, which sent them off for good and all. But what is wonderful to tell, we ourselves after all this success at the very same time also retired, but indeed we did not then know that victory was ours. However we rallied, but all that could now be mustered was about 13 files private with our Colonel and four other officers one of which I was so fortunate to be. With this remnant we returned again to the charge, but to our unspeakable joy no opponents could be found. It is astonishing, that this victory was gained by six English regiments of foot, without their grenadiers, unsupported by cavalry or cannon, not even their own battalion guns, in the face of a dreadful battery so near as to tear them with grape-shot, against forty battalions and thirty-six squadrons, which is directly the quantity of the enemy which fell to their share.

It is true that two Hanoverian regiments were engaged on the left of the English, but so inconsiderably as to lose only 50 men between them. On the left of the army the grenadiers, who now form a separate body, withstood a furious cannonade. Of the English there was only killed one captain and one sergeant; some Prussian dragoons were engaged and did good service. Our artillery which was stationed in different places, also behaved well, but the grand attack on which depended the fate of the day, fell to the lot of the six English regiments of foot. From this account the Prince might be accused of misconduct for trusting the issue of so great an event to so small a body, but this affair you will have soon enough explained to the disadvantage of a great men whose easy part, had it been properly acted, must have occasioned to France one of the greatest overthrows it ever met with. The sufferings of our regiment will give you the best notion of the smartness of the action. We actually fought that day not more than 480 private and 27 officers, of the first 302 were killed and wounded, and of the latter 18. Three lieutenants were killed on the spot, the rest are only wounded, and all of them are in a good way except two. Of the officers who escaped there are only four who cannot show some marks of the enemy's good intentions, and as perhaps you may be desirous to know any little risks that I might have run, I will mention those of which I was sensible. At the beginning of the action I was almost knocked off my legs by my three right hand men, who were killed and drove against me by a cannon ball, the same ball also killed two men close to Ward, whose post was in the rear of my platoon, and in this place I will assure you that he behaved with the greatest bravery, which I suppose you will make known to his father and friends. Some time after I received from a spent ball just such a rap on my collar-bone as I have frequently from that once most dreadful weapon, your crooked-headed stick; it just welled and grew red enough to convince the neighbours that I was not fibbing when I mentioned it. I got another of these also on one of my legs, which gave me about as much pain, as would a tap of Miss Mathews's fan. The last and greatest misfortune of all fell to the share of my poor old coat for a musket ball entered into the right skirt of it and made three holes. I had almost forgot to tell you that my spontoon was shot through a little below my hand; this disabled it, but a French one now does duty in its room. The consequences of this affair are very great, we found by the papers, that the world began to give us up, and the French had swallowed us up in their imaginations. We have now pursued them above 100 miles with the advanced armies of the hereditary prince, Wanganheim, and Urff in our front, of whose success in taking prisoners and baggage, and receiving deserters, Francis Joy will give you a better account than I can at present. They are now entrenching themselves at Cassel, and you may depend on it they will not show us their faces again during this campaign.

I have the pleasure of being able to tell you that Captain Rainey is well; he is at present in advance with the Grenadiers plundering French baggage and taking prisoners. I would venture to give him forty ducats for his share of prize money.

I have now contrary to my expectations and in spite of many interruptions wrote you a long letter, this paper I have carried this week past in my pocket for the purpose, but could not attempt it before. We marched into this camp yesterday evening, and shall quit it early in the morning. I wrote you a note just informing you that I was well the day after the battle; I hope you will receive it in due time. Be pleased to give my most affectionte duty to my uncles and aunts...

The noise of the battle frightened our sutler's wife into labour the next morning. She was brought to bed of a son, and we have had him christened by the name of Ferdinand.[9]

Aftermath

Prince Ferdinand's army suffered nearly 2,800 men killed and wounded; the French lost about 7,000 men.[2] In the wake of the battle the French retreated southwards to Kassel. The defeat ended the French threat to Hanover for the remainder of that year.

Ferdinand's cavalry commander, Lieutenant General Lord George Sackville, was accused of ignoring repeated orders to bring up his troopers and charge the enemy until it was too late to make any difference. In order to clear his name he requested a court martial, but the evidence against him was substantial and the court martial declared him "...unfit to serve His Majesty in any military Capacity whatever." [10] Sackville would later reappear as Lord George Germain and bear a major portion of the blame for the outcome of the American Revolution while Secretary of State for the Colonies.

In Britain the result at Minden was widely celebrated and was seen as part of Britain's Annus Mirabilis of 1759 also known as the "Year of Victories", although there was some criticism of Ferdinand for not following up his victory more aggressively. When George II of Great Britain learned of the victory, he awarded Ferdinand £20,000 and the Order of the Garter.[11] Minden further boosted British support for the war on the continent, and the following year a "glorious reinforcement" was sent, swelling the size of the British contingent in Ferdinand's army.[12]

In France the reaction to the result was severe. The Duc de Choiseul, the French Chief Minister, wrote "I blush when I speak of our army. I simply cannot get it into my head, much less into my heart, that a pack of Hanoverians could defeat the army of the King". To discover how the defeat had occurred and to establish the general condition of the army, Marshal d'Estrées was sent on a tour of inspection. Marshal de Contades was subsequently relieved of his command and replaced by the Duc de Broglie.[13]

Michel Louis Christophe Roch Gilbert Paulette du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette and colonel aux Grenadiers de France, was killed when he was hit by a cannonball in this battle.[14] La Fayette's son, Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, was not even two years old at that time. Jean Thurel, the 59-year-old French fusilier, was severely wounded, receiving seven sword slashes, six of them to the head.[15]

Minden in regimental tradition

The British regiments which fought at Minden (with the successor British army unit which still uphold their traditions) were:

- Royal Artillery

- 12th of Foot (Suffolk Regiment), now part of The Royal Anglian Regiment

- 20th Foot (Lancashire Fusiliers), now part of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers

- 23rd Foot (Royal Welch Fusiliers), now the 1st Battalion, The Royal Welsh (Royal Welch Fusiliers)

- 25th Foot (King's Own Scottish Borderers), now The Royal Scots Borderers (1st Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland)

- 37th Foot (Royal Hampshire Regiment), now part of the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment

- 51st Foot (King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry), now part of The Rifles

The descendants of these units are still known as "the Minden Regiments."

When the British infantry and artillery were first advancing to battle they passed through some German gardens and the soldiers picked roses and stuck them in their coats. In memory of this, each of the Minden regiments marks 1 August as Minden Day.[16] On that day the men of all ranks wear roses in their caps.[17] The Royal Regiment of Artillery wear red roses, The Royal Anglians, The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers and the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment wear red and yellow roses; the Scots wear red; the Rifles wear Yorkshire white roses. From this tradition, and to mark the heroism of the Yorkshiremen who fought, 1 August has been adopted as Yorkshire Day. The Royal Welch Fusiliers do not wear roses on Minden Day as the Minden Rose was incorporated into the roundel of their cap badge and so is worn every day of the year, though retired members of the Regiment do sport roses in the lapels on Minden Day. Artillery regiments with Minden associations (see below) also wear red roses.

This British victory was also recalled in the British Army's Queen's Division which maintained the "Minden Band" until its 2006 amalgamation with the "Normandy Band" to form the Band of the Queen's Division.

Two batteries from the Royal Regiment of Artillery carry the Minden battle honour. Soldiers from both 12 (Minden) Battery and 32 (Minden) Battery traditionally wear a red rose in their headdress on 1 August every year, both batteries celebrate Minden Day every year. A proud tradition exists: 'Once a Minden Man, always a Minden Man.'.

Every year from 1967 to 2015, six red roses have been anonymously delivered to the British consulate in Chicago on 1 August. Until they were closed, roses were also delivered to consulates in Kansas City, Minneapolis and St. Louis, starting as early as 1958 in Kansas City. A note that comes with the roses lists the six regiments and says, "They advanced through rose gardens to the battleground and decorated their tricorne hats and grenadier caps with the emblem of England. These regiments celebrate Minden Day still, and all wear roses in their caps on this anniversary in memory of their ancestors." The Embassy has asked for the name of the sender (on numerous occasions) so that they may thank the individual in person, but the identity of the donor remains a mystery.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

In poetry

- Erasmus Darwin, Death of Eliza at the Battle of Minden

- Rudyard Kipling, "The Men That Fought at Minden" in Barrack-Room Ballads

In Freemasonry

During the Cold War by 1972 some 50,000 British Forces were deployed to Germany. Minden at the time was well established as a Garrison with the Garrison HQ located within Kingsley Barracks, later also, in 1976 the home of HQ 11th Armoured Brigade. Since 1957, within BAOR (British Army of the Rhine), 11 British speaking Lodges had been founded under the Grand Land Lodge of British Freemasons in Germany. The closest Lodge at the time nearest to Minden was Britannia Lodge No. 843 of Bielefeld, some 50 Km distance and, at the time, a 1 hour drive. A meeting was held in the Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers (REME) Officers Mess, Johansen Str 1, Minden, on 24 June 1972, to determine whether it would be plausible to form a resident Lodge in Minden to fulfill the needs of Freemasons among the military serving there. This was agreed and a petition was sent to the Grand Land Master for review. Once the proposed By laws had been approved by the Grand Secretary the petition was signed and permission to form the Lodge was given on 13 August 1972. The consecration ceremony took place on 28 October 1972, but was held in Herford due to insufficient space the intended Lodge rooms could provide in Minden.

The name chosen for the Lodge was The Rose of Minden Lodge Number 918. The name, suggested by Brother B Potter at the initial meeting, was agreed as a being proper and sincere tribute to the British Forces serving in Minden, from which, many of its new and intended members were stationed.

When the Cold War ended in 1991 Minden was closed as a Garrison, meaning that Lodge membership dwindled as the troops moved away. To counteract this migration of members, it was decided to move the Lodge to Herford which was to become the home of 1st UK Armoured Division. The Lodge resides, and still does to this, at the place where it was originally consecrated and shares the Lodge house "Logenhaus Unter den Linden 34, Herford" with 4 other German Masonic Lodges.

Now that the British Forces contingent has been reduced again to a bare minimum as part of the 2010 UK's "Strategic Defence and Security Review," (SDR), the Lodge now recruits its members from the expatriates living in and around the area, this also include German and other nationals interested in practicing Freemasonry in the English language following the English constitution provided by the United Grand Lodge of England. However, many of the members today who have decided to remain in Germany used to serve in the successors of above mention units and celebrate the 1 August as Minden Day.

See also

- John Manners, Marquess of Granby

- Granville Elliott

- Great Britain in the Seven Years War

Notes

References

- Mackesy: The Coward of Minden 92

- Mackesy: The Coward of Minden 141

- Dull p.94-100

- Dull p.119-123

- Szabo p.215-19

- McLynn p.268 & Szabo p.257

- Szabo p.257-259

- "Contades selbst war darüber so erstaunt, daß er gestand, er habe gesehen, was er nie für möglich gehalten, daß eine einzige Linie Fußvolfs drei in Schlachtordnung aufgestellte Reiterlinien durchbrochen und über den Haufen geworfen." Stenzel (1854): 204. "Contades said bitterly: 'I have seen what I never thought to be possible—a single line of infantry break through three lines of cavalry, ranked in order of battle, and tumble them to ruin!'" Trans. Carlyle (1869): 44.

- Wylly, H.C. History of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, I:48-49.

- The Proceedings of a General Court-Martial … upon the trial of Lord George Sackville (London: 1760), p. 224

- McLynn p.279

- Dull p.179

- Szabo p.262

- Gottschalk, Louis (2007). Lafayette comes to America. Read Books. pp. 3–5. ISBN 1-4067-2793-8.

- La Sabretache (societe d'etudes d'histoire militaire) (1895). "Le médaillon de vétérance". Carnet de la Sabretache: revue militaire rétrospective (in French). III. Nancy, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, France: Berger-Levrault et Cie. pp. 264–73. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- C. S. Forester, The General.

- https://www.forces.net/news/what-minden-day-why-should-you-care

- Daniel, Jonathan (31 July 2013). "A thorny case for Sherlock Holmes". FCO Blogs. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Olmstead, Bob (1 August 1987). "Mystery roses pay yearly salute to Brits". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Smith, Zay N. (3 August 1990). "Consulate's roses still bear scent of mystery". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Baldacci, Leslie (2 August 2005). "Flower deliveries to British consulate cloaked in mystery". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Sneed, Michael (2 August 2007). "A rose is a rose ...". Chicago Sun-Times.

- "Minden Roses". Lancashire Fusiliers. 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

Bibliography

- Contades, Louis Georges Érasme, de (1759). Lettres du Marêchal Duc de Belleisle au Marêchal de Contades]; avec des Extraits de quelques unes de celles de ce dernier; trouvées parmi ſes Papiers, après la Bataille de Minden: Suivant la copie de Londres, imprimée ſur les Originaux, par autorité du Gouvernment de la Grand Bretagne (in French). La Haye: Chez Pierre de Hondt.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dull, Jonathan R. (2005). The French Navy and the Seven Years' War. University of Nebraska.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, Ralph; Lieutenant General George Germain, Viscount of Sackville (1760). A Plan of the Battle of Thonhausen near Minden: on the 1st of August 1759 (PDF). National Library of Scotland Annual Review 2005–2006. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Knowles, Lees (1914). Minden and the Seven Years War. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Company.

- Mackesy, Piers (1979). The Coward of Minden: The Affair of Lord George Sackville. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-17060-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLynn, Frank (2005). 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World. Pimlico.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin Steffen, ed. (2008). Die Schlacht bei Minden: Weltpolitik und Lokalgeschichte (in German). Verlag: J.C.C. Bruns'. ISBN 978-3-00-026211-1.

- Stenzel, Gustav Adolf Harald (1854). Geschichte des Preussischen Staats. Fünfter Band 1756–1763 (in German). Hamburg.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Szabo, Franz A.J. (2008). The Seven Years War in Europe, 1757-1763. Pearson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Battle of Minden at www.britishbattles.com

- Battle of Minden at amtage.de (in German)

- A Map of That Part of Westphalia, in Which the French Army Where Defeated Aug. 1, 1759

- Battle of Minden documented in English maps

- Minden mystery roses

- Official British Army website - news of the British Army's traditional commemoration of Minden Day 2012

- The Royal Scottish Borderers (1 SCOTS) Minden Day parade, Berwick Upon Tweed 2008. Royal Scottish Borderers are the descendant of Kings Own Scottish Borderers and uphold their traditions. Note the red rose in each Tam O'Shanter alongside the black hackle