Battle of Neuensund

The Battle of Neuensund was a smaller battle at Neuensund of the Seven Years' War between Swedish and Prussian forces fought on September 18, 1761. The Swedish force under the command of Jacob Magnus Sprengtporten managed to rout the Prussian forces commanded by Wilhelm Sebastian von Belling.[4]

Prelude

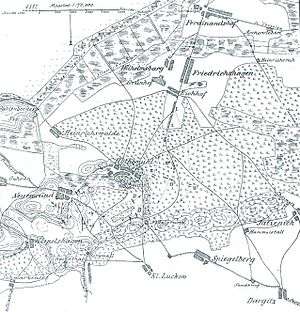

By mid September 1761, after the capture of Platen by the Russians, the small Prussian corps under the command of Stutterheim had been ordered to leave Western Pomerania and to take position at Stettin. On September 15, according to his orders, Stutterheim marched towards Stettin. This left only Belling's corps to defend Western Pomerania against the Swedes. By this date, the Swedes had, at Wollin and in Pomerania, a total of 13,791 men (including 3,098 cavalry with 2,988 horses, and 1,152 infantrymen counting Nylands Infantry who served with the artillery). The departure of Stutterheim offered to Ehrensvärd the opportunity to retake the initiative and to launch another offensive against Belling's small force. The Swedish army concentrated in 2 columns, one under Lybecker, the other under Sprengtporten, and advanced on Belling's corps in a pincer movement.

On September 17, Belling tried to stop Lybecker's column, engaging it at the battle of Kosabroma. His attack nearly succeeded but he was forced to retire leaving Goltz at Kosabroma to delay Lybecker. On September 18, Belling withdrew towards Rothemühl where 2 grenadier bns, sent from Stettin as reinforcements, were supposed to join him. The same day, Sprengtporten's vanguard pursued Knobelsdorf's detachment (200 infantry, 50 hussars) which had been defending Ferdinandshof. Knobelsdorf skirmished with light troops of the Swedish vanguard (Frikompanie Lundberg and Silverstolpe) while retreating on Rothemühl. On his way, Knobelsdorf had been reinforced by 2 Freicompanien from Stettin who delayed the Swedes pursuit. Sprengtporten sent 1 bn of Skaraborgs Infantry towards Rothemühl while he marched to Torgelow with the rest of his column.

Battle

On September 18, Belling reached Neuensund, about 6 km west of Rothemühl. The Prussian vanguard now consisted of 3 coys of Frei-Infanterie von Hordt, Hullesen Freikompanie and Kenewitz Freikompanie and 100 hussars. It took position opposite to the Skaraborgs Infantry by occupying Rothemühl. The Swedish positions being quite strong, Belling's vanguard cannonaded it without attempting any assault. Belling was still at Neuensund with the rest of his infantry (5 coys), waiting for the arrival of his 2 grenadier battalions from Pasewalk. They were not yet arrived when Belling heard the sounds of an engagement on his rear. It was Lybecker's column who had engaged Goltz's detachment (2 coys, 2 sqns). Goltz had to delay Lybecker's advance to give Belling enough time to defeat Sprengtporten. Lybecker, thinking that he was facing Belling's entire corps, limited his action to musketry fire, awaiting Sprengtporten's arrival.

At 11:00 AM, the 2 Prussian grenadier battalions finally arrived at Neuensund. Belling immediately sent them in a flanking movement against the forest. In the same time, Sprengtportens' corps appeared on the road from Ferdinandshof. He deployed his column to launch a counter-attack on Belling. Frikompanie Lille and Sprengtporten formed on the right wing, the Swedish grenadiers in the centre and Frikompanie Lundberg and Ehrenhielm on the left wing. The cavalry and the rest of the infantry were kept in reserve. The first Prussian line consisted, from right to left, of Grenadier Battalion Ingersleben, Grenadier Battalion S54/S56 Rothkirch, II./Frei-Infanterie Hordt and II./Belling Hussars. The two lines came to contact and heavy fighting started. Grenadier Battalion Ingersleben charged the Frikompanie Lille and Sprengtporten at the point of the bayonet, broke them and continued its advance, leaving Grenadier Battalion S54/S56 Rothkirch and II./Frei-Infanterie Hordt behind. Grenadier Battalion Ingersleben advanced so rapidly on the Swedish positions that it was soon isolated. In the vicinity of the village of Neuensund, Sprengtporten's younger brother Göran Magnus distinguished himself with his own and Lillies Frikompanie. He fooled and trapped Grenadier Battalion Ingersleben in a small wood where these grenadiers were outflanked and attacked by his older brother's infantry: Cederström Grenadiers, Frikompanie Lundberg and Frikompanie Silfverströms who opened a heavy fire on the exposed flank of the unprotected flank Grenadier Battalion Ingersleben. Attacked from every side it was forced to retreat losing 2/3 of his men. Its withdrawal was covered by Grenadier Battalion S54/S56 Rothkirch and Belling Hussars.

Fearing to be caught between the two Swedish columns, Belling resolved to retire to Taschenberg and Gehren, sending back the 2 grenadier battalions to Pasewalk. He first marched westwards, turning southwards on Strasburg at sunset. The columns of Lybecker and Sprengtporten made a junction at Schönhausen and marched back to Woldegk and Strasburg.

Outcome

In this combat, the Prussians lost about 510 men[3] (Grenadier Battalion Ingersleben alone probably lost 11 NCOs and 287 men, Grenadier Battalion S54/S56 Rothkirch 2 killed, and 1 officer and 3 privates wounded) four officers and 200 men were killed and another 300 men along with six officers captured.[2] The Swedes lost 1 officer, 37 men killed; 5 officers and 76 men wounded; 9 missing and 26 taken prisoners. The combat had almost no influence on the results of the campaign.

Notes

- Nordisk Familjebok

- Flykten från Berlin, Gunnar W Bergman. C. 21.

- The Seven Years' War: Global Views, Mark Danley, Patrick Speelman (2012), Brill. p. 160.

- This article is heavily based on Kronoskaf

Sources

- Kessel E., Das Ende des Siebenjährigen Krieges 1760-1763, Hrgb. von T. Linder, t. 1, Padeborn – München – Wien – Zürich 2007

- Sharman A., Sweden's Role in the Seven Years' War: 1761, Seven Years' War Association Journal, Vol. XII, 2002.

- Sulicki K. M., Der Siebenjährigen Kriegin in Pommern und in den benachbarten Marken. Studie des Detaschmentes und des kleinen Krieges, Berlin 1867.