Basilica Julia

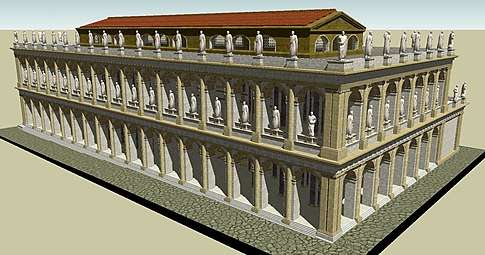

The Basilica Julia (Italian: Basilica Giulia) was a structure that once stood in the Roman Forum. It was a large, ornate, public building used for meetings and other official business during the Roman Empire. Its ruins have been excavated. What is left from its classical period are mostly foundations, floors, a small back corner wall with a few arches that are part of both the original building and later Imperial reconstructions and a single column from its first building phase.

| Basilica Julia | |

|---|---|

Basilica Julia | |

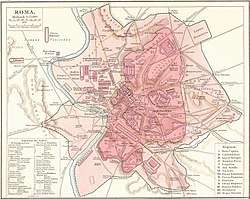

| Location | Regione VIII Forum Romanum |

| Built in | 46 BC |

| Built by/for | Gaius Julius Caesar |

| Type of structure | Basilica |

| Related | Roman Forum |

| |

The Basilica Julia was built on the site of the earlier Basilica Sempronia (170 BC) along the south side of the Forum, opposite the Basilica Aemilia. It was initially dedicated in 46 BC by Julius Caesar, with building costs paid from the spoils of the Gallic War, and was completed by Augustus, who named the building after his adoptive father. The ruins which have been excavated date to a reconstruction of the Basilica by the Emperor Diocletian, after a fire in 283 AD destroyed the earlier structure.[1]

History and use

Ancient Rome

The first iteration of the Basilica Julia was begun around 54 BC by Julius Caesar, though it was left to his heir Augustus to complete the construction and name it in honor of his adoptive father. The basilica was built over the remains of two important Republican structures: the Basilica Sempronia, which was demolished by Caesar to make way for the new basilica, and pre-dating both, the house of Scipio Africanus, Rome's legendary general. The Basilica Sempronia was built in 169 BC by Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and required the demolition of the house of Africanus and a number of shops to make room.[2][3]

The first Basilica Julia burned in 9 AD, shortly after completion, but it was reconstructed, enlarged, and rededicated to Augustus' adoptive sons Gaius and Lucius in 12 AD.[4][5] The Basilica was restored after a fire in 199 AD by Septimius Severus, and later reconstructed by the Emperor Diocletian after another fire in 283 AD.[4]

The Basilica is bordered on its short sides by two important ancient roads which led from the Tiber to the Forum: the Vicus Jugarius to the west, and the Vicus Tuscus to the east.[6] The ground floor was divided into five east-west aisles inside, with the central aisle forming a large hall that measured 82x18 meters, sheltered by a three-story high roof.[7] The adjoining aisles to the north and south of the central hall were divided by marble-faced brick columns which supported concrete arcades; the columns in turn supported the upper level of the basilica, which was used as a public gallery.[5] The floor of the central hall was paved in colorful polychrome marble slabs, contrasting with the plain white marble of the adjoining aisles.[8] The Basilica's façade as it appeared after the Augustan restoration was two stories high and arcaded, with engaged Carrara marble columns decorating the piers between the arches on both levels.[9]

The Basilica housed the civil law courts and tabernae (shops), and provided space for government offices and banking. In the 1st century, it also was used for sessions of the Centumviri (Court of the Hundred), who presided over matters of inheritance. In his Epistles, Pliny the Younger describes the scene as he pleaded for a senatorial lady whose 80-year-old father had disinherited her ten days after taking a new wife. Suetonius states that Caligula greatly enjoyed showering the crowd in the forum below with money while standing on the roof of the Basilica Julia.[10][11]

It was the favorite meeting place of the Roman people. This basilica housed public meeting places and shops, but it was mainly used as a law court. On the pavement of the portico, there are diagrams of games scratched into the white marble. One stone, on the upper tier of the side facing the Curia, is marked with an eight by eight square grid on which games similar to chess or checkers could have been played. The last recorded restoration of the Basilica Julia was undertaken by the Urban Prefect Gabinius Vettius Probianus in 416 AD, who also relocated several Greek statues by the sculptors Polykleitos and Timarchus for display near the center of the façade. The inscribed bases of these statues recording the restoration still survive.[12][4]

Late antiquity & medieval era

_-_Roman_Forum_-_Rome_2016.jpg)

The Basilica Julia was partially destroyed in 410 AD when the Visigoths sacked Rome[13] and the site slowly fell into ruin over the centuries. The marble was especially valuable in the medieval and early modern eras for burning into lime, a material used to make mortar. The remnants of kilns on the site, which were found in early excavations, confirmed that most of the building's components were destroyed in this way.[5]

Part of the remains of the basilica were converted into a church, generally identified as that of Santa Maria de Cannapara which is mentioned in catalogues from the 12th through the 15th centuries.[5] Other parts of the basilica were sectioned off in the medieval period for the use of different trades. The marble workers, or marmorarii, took up most of the remaining space not occupied by the church in the 11th century for re-fashioning and selling marble architectural ornaments; the eastern aisle was occupied by the rope-makers and was called the Cannaparia as a result. In the 16th century, the long-buried site of the Basilica was used as a burial ground for patients of the adjacent Ospedale della Consolazione.[14]

The building consists now only of a rectangular area, levelled off and raised about one metre above ground level, with jumbled blocks of stone lying within its area. A row of marble steps runs full length along the side of the basilica facing the Via Sacra, and there is also access from a taller flight of steps (the ground being lower here) at the end of the basilica facing the Temple of Castor and Pollux.

Archaeology and excavation

The earliest excavations of the Basilica Julia in the late 15th and 16th centuries were destructive, their main purpose being to recover valuable travertine and marble for re-use. In 1496, travertine was mined from the ruins to build the façade of the Palazzo Torlonia, the Roman palace of Cardinal Adriano Castellesi.[15] There were also excavations in 1500, 1511-12, and 1514, as well as a destructive excavation in 1742 which uncovered the portion of the Cloaca Maxima which runs underneath the basilica. In the process the giallo antico yellow marble which covered the floor was stripped and sold to a stone-cutter.[15]

The Chevalier Frédenheim also undertook excavations between November, 1788 and March, 1789; Frédenheim dismantled much of the remaining colored marble pavement and removed many architectural fragments.[16] The site was excavated by Pietro Rosa in 1850 who reconstructed a single marble column and travertine supports. In 1852 segments of concrete vaulting with stuccowork coffering was unearthed but later destroyed in 1872.[17]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basilica Julia (Rome). |

- Samuel Ball Platner & Thomas Ashby (1929). "A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome". Oxford University Press. p. 78-80.

- Filippo Coarelli (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press. p. 71-73.

- Gilbert Gorski (2015). The Roman Forum: A Reconstruction & Architectural Guide. Cambridge University Press. p. 12, 248.

- John Henry Middleton (1892). The Remains of Ancient Rome. p. 270.

- Samuel Ball Platner & Thomas Ashby (1929). "A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome". Oxford University Press. p. 78-80.

- Filippo Coarelli (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press. p. 71.

- Filippo Coarelli (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press. p. 71-73.

- John Henry Middleton (1892). The Remains of Ancient Rome. p. 272.

- John Henry Middleton (1892). The Remains of Ancient Rome. p. 271.

- John Henry Middleton (1892). The Remains of Ancient Rome. p. 273.

- Suetonius, Caligula, 37

- Filippo Coarelli (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press. p. 71-73.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2013-05-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome; a companion book for students and travelers. Houghton Mifflin & Co. p. 242.

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome;a companion book for students and travelers. Houghton Mifflin & Co. p. 227.

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome; a companion book for students and travelers. Houghton Mifflin & Co. p. 227, 249.

- Claridge, Amanda; Toms, Judith; Cubberley, Tony (March 1998). Rome: an Oxford archaeological guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-19-288003-1.

External links

| Library resources about Basilica Julia |

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Basilica Julia | Art Atlas