Battle of Thapsus

The Battle of Thapsus was an engagement in Caesar's Civil War that took place on February 6, 46 BC[1] near Thapsus (in modern Tunisia). The Republican forces of the Optimates, led by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Scipio, were decisively defeated by the veteran forces loyal to Julius Caesar. It was followed shortly by the suicides of Scipio and his ally, Cato the Younger.

| Battle of Thapsus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Caesar's Civil War | |||||||

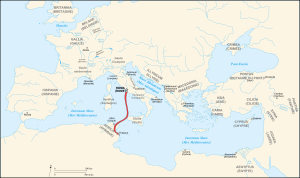

Thapsus in relation to Rome | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Populares |

Optimates Numidia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gaius Julius Caesar |

Metellus Scipio Marcus Petreius Juba I of Numidia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 50,000 (at least 8 legions), 5,000 cavalry |

72,000 (at least 12 legions), 14,500 cavalry Juba's allied troops with 60 elephants | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| nearly 1,000 | about 10,000 | ||||||

Prelude

In 49 BC, the last Republican civil war was initiated after Julius Caesar defied senatorial orders to disband his army following the conclusion of hostilities in Gaul. He crossed over the Rubicon river with the 13th Legion, a clear violation of Roman Law, and marched to Rome. The Optimates fled to Greece under the command of Pompey since they were incapable of defending the city of Rome itself against Caesar. Led by Caesar, the Populares followed, but were greatly outnumbered and defeated in the Battle of Dyrrhachium. Still outnumbered, Caesar recovered and went on to decisively defeat the Optimates under Pompey at Pharsalus. Pompey then fled to Egypt, where to Caesar's consternation, Pompey was assassinated. The remaining Optimates, not ready to give up fighting, regrouped in the African provinces. Their leaders were Marcus Cato (the younger) and Caecilius Metellus Scipio. Other key figures in the resistance were Titus Labienus, Publius Attius Varus, Lucius Afranius, Marcus Petreius and the brothers Sextus and Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey's sons). King Juba I of Numidia was a valuable local ally. After the pacification of the Eastern provinces, and a short visit to Rome, Caesar followed his opponents to Africa and landed in Hadrumetum (modern Sousse, Tunisia) on December 28, 47 BC. After landing, Caesar's forces were engaged by the Optimates led by Petreius and Labienus, Scipio being absent. The result was ultimately indecisive and both sides retreated.[2]

The Optimates gathered their forces to oppose Caesar with astonishing speed. Their army included 40,000 men (about 8 legions), a powerful cavalry force led by Caesar's former right-hand man, the talented Titus Labienus, forces of allied local kings, and 60 war elephants. The two armies engaged in small skirmishes to gauge the strength of the opposing force, during which two legions switched to Caesar's side. Meanwhile, Caesar expected reinforcements from Sicily. In the beginning of February, Caesar arrived in Thapsus and besieged the city, blocking the southern entrance with three lines of fortifications. The Optimates, led by Metellus Scipio, could not risk the loss of this position and were forced to accept battle.

Battle

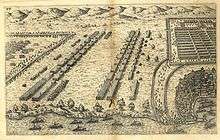

Metellus Scipio's army circled Thapsus in order to approach the city by its northern side. Anticipating Caesar's approach, it remained in tight battle order flanked by its elephant cavalry. Caesar's position was typical of his style, with him commanding the right side and the cavalry and archers flanked. The threat of the elephants led to the additional precaution of reinforcing the cavalry with five cohorts.

One of Caesar's trumpeters sounded the battle. Caesar's archers attacked the elephants, causing them to panic and trample their own men. The elephants on the left flank charged against Caesar's center, where Legio V Alaudae was placed. This legion sustained the charge with such bravery that afterwards they wore an elephant as a symbol. After the loss of the elephants, Metellus Scipio started to lose ground. Caesar's cavalry outmaneuvered its enemy, destroyed the fortified camp, and forced its enemy into retreat. King Juba's allied troops abandoned the site and the battle was decided.

Around ten thousand enemies were killed, those surviving the battle being put to the sword by the furious soldiers in spite of Caesar's plea to spare them.[3] Plutarch reports[4] that according to some sources Caesar had an epileptic seizure during the battle. Scipio himself escaped, only to commit suicide months later in a naval battle near Hippo Regius.

Aftermath

Following the battle, Caesar renewed the siege of Thapsus, which eventually fell. Caesar proceeded to Utica, where Cato the Younger was garrisoned. On the news of the defeat of his allies, Cato committed suicide. Caesar was upset by this and is reported by Plutarch to have said: "Cato, I must grudge you your death, as you grudged me the honour of saving your life."

The battle preceded peace in Africa—Caesar pulled out and returned to Rome on July 25 of the same year. Opposition, however, would rise again. Titus Labienus, the Pompeian brothers and others had managed to escape to the Hispania provinces. The civil war was not finished, and the Battle of Munda would soon follow. The Battle of Thapsus is generally regarded as marking the last large scale use of war elephants in the West.[5]

Notes

- The date is that of the Roman calendar prior to the reforms of Julius Caesar. By the Julian calendar, it is February 7, 46 BC.

- "Labienus and Petreius, Scipio's lieutenants, attacked him, defeated him badly,[..] Petreius, thinking that he had made a thorough test of the army and that he could conquer whenever he liked, drew off his forces, saying to those around him, 'Let us not deprive our general, Scipio, of the victory.' In the rest of the battle it appeared to be a matter of Caesar's luck that the victorious enemy abandoned the field when they might have won." Appian, Civil Wars, 95 , cf. De Bello Africo, 15 for an alternative account of the engagement by a Caesarian.

- De Bello Africo, 85 "In short all Scipio's soldiers, though they implored the protection of Caesar, were in the very sight of that general, and in spite of his entreaties to his men to spare them, without exception put to the sword."

- Life of Caesar 53.5

- Gowers, African Affairs.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |