First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate (60–53 BC) was an informal alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Marcus Licinius Crassus.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a complex set of checks and balances designed to prevent a man from rising above the rest and creating a monarchy. In order to bypass these constitutional obstacles, Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus forged a secret alliance in which they promised to use their respective influence to help each other. According to Goldsworthy, the alliance was "not at heart a union of those with the same political ideals and ambitions", but one where "all [were] seeking personal advantage." As the nephew of Gaius Marius, Caesar was at the time very well connected with the Populares faction, which pushed for social reforms. He was moreover Pontifex Maximus—the chief priest in the Roman religion—and could significantly influence politics, notably through the interpretation of the auspices. Pompey was the greatest military leader of the time, having notably won the wars against Sertorius (80–72 BC), Mithridates (73–63 BC), and the Cilician Pirates (66 BC). Although he won the war against Spartacus (73–71 BC), Crassus was mostly known for his fabulous wealth, which he acquired through intense land speculation. Both Pompey and Crassus also had extensive patronage networks. The alliance was cemented with the marriage of Pompey with Caesar's daughter Julia in 59 BC.

Thanks to this alliance, Caesar thus received an extraordinary command over Gaul and Illyria for five years, so he could start his conquest of Gaul. In 56 BC the Triumvirate was renewed at the Lucca Conference, in which the triumvirs agreed to share the Roman provinces between them; Caesar could keep Gaul for another five years, while Pompey received Hispania, and Crassus Syria. The latter embarked into an expedition against the Parthians to match Caesar's victories in Gaul, but died in the disastrous defeat of Carrhae in 53 BC.

The death of Crassus ended the Triumvirate, and left Caesar and Pompey facing each other; their relationship had already degraded after the death of Julia in 54 BC. Pompey then sided with the Optimates, the conservative faction opposed to the Populares—supported by Caesar—and actively fought Caesar in the senate. In 49 BC, with the conquest of Gaul complete, Caesar refused to release his legions and instead invaded Italy from the north by crossing the Rubicon with his army. The following civil war eventually led to Caesar's victory over Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC and the latter's assassination in Ptolemaic Egypt where he fled after the battle. In 44 BC Caesar was assassinated in Rome and the following year his adopted son Octavian (later known as Augustus) formed the Second Triumvirate with Marcus Antonius and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.

Background

In the background of the formation of this alliance were the frictions between two political factions of the Late Republic, the populares and optimates. The former drew support from the plebeians (the commoners, the majority of the population). Consequently, they espoused policies addressing the problems of the urban poor and promoted reforms that would help them, particularly redistribution of land for the landless poor and farm and debt relief. It also challenged the power the nobiles (the aristocracy) exerted over Roman politics through the senate, which was the body that represented its interests. The Optimates were an anti-reform conservative faction that favoured the nobles, and also wanted to limit the power of the plebeian tribunes (the representatives of the plebeians) and the Plebeian Council (the assembly of the plebeians) and strengthen the power of the senate. Julius Caesar was a leading figure of the populares. The origin of the process that led to Caesar seeking the alliance with Pompey and Crassus traces back to the Second Catilinarian conspiracy, which occurred three years earlier in 63 BC when Marcus Tullius Cicero was one of the two consuls.

In 66 BC Catiline, the leader of the plot, presented his candidacy for the consulship, but he was charged with extortion and his candidacy was disallowed because he announced it too late.[1] In 65 BC he was brought to trial along with other men who had carried out killings during the proscriptions (persecutions) of Lucius Cornelius Sulla when the dictator had declared many of his political opponents enemies of the state (81 BC).[2] He received the support of many prominent men and he was acquitted through bribery.[3][4] In 63 BC Catiline was a candidate for the consulship again. He presented himself as the champion of debtors.[5][6] Catiline was defeated again and Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida were elected. He plotted a coup d'état together with a group of fellow aristocrats and disaffected veterans as a means of preserving his dignitas.[7] One of the conspirators, Gaius Manlius, assembled an army in Etruria and civil unrest was prepared in various parts of Italy. Catiline was to lead the conspiracy in Rome, which would have involved arson and the murder of senators. He was then to join Manlius in a march on Rome. The plot was to start with the murder of Cicero. Cicero discovered this, exposed the conspiracy, and produced evidence for the arrest of five conspirators. He had them executed without trial with the backing of a final decree of the Senate – a decree the senate issued at times of emergency.[8][9] This was done because it was feared that the arrested men might be freed by other plotters. Julius Caesar opposed this measure. When Catiline heard of this he led his forces in Pistoria (Pistoia) with the intention of escaping to northern Italy. He was engaged in battle and defeated.[10]

The summary executions were an expedient to discourage further violence. However, this measure, an unprecedented assertion of senatorial power over the life and death of Roman citizens, backfired for the optimates. It was seen by some as a violation of the right to a trial and led to charge of repressive governance, and gave the populares ammunition with which to challenge the notion of aristocratic dominance in politics and the prestige of the senate. Cicero's speeches in favour of the supremacy of the senate made matters worse. In 63 BC the plebeian tribunes Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos Iunior and Calpurnius Bestia, supported by Caesar, sharply criticized Cicero, who came close to being tried. The senate was also attacked on the ground that it did not have the right to condemn any citizens without a trial before the people.[11] Caesar, who was a praetor, proposed that Catullus, a prominent optimate, be relieved from restoring the temple of Jupiter and that the job be given to Pompey. Metellus Nepos proposed a law to recall Pompey to Italy to restore order. Pompey was away commanding the final phase of the Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC) in the east. Nepos was strongly opposed by Cato the Younger, who in that year was a plebeian tribune and a staunch optimate. The dispute came close to violence; Nepos had armed some of his men. According to Plutarch, the senate announced the intention to issue a final decree to remove Nepos from his office but Cato opposed it.[12] Nepos went to Asia to inform Pompey about the events, even though, as a plebeian tribune, he had no right to be absent from the city.[13] Tatum maintains that Nepos leaving the city even though plebeian tribunes were not allowed to do so was 'a gesture demonstrating the senate's violation of the tribunate.'[14] Caesar also brought a motion to have Pompey recalled to deal with the emergency. Suetonius wrote that Caesar was suspended by a final decree. At first Caesar refused to stand down, but he retired to his home when he heard that some people were ready to coerce him by force of arms. The next day the people demonstrated in favour of his reinstatement and were becoming riotous, but Caesar "held them in check." The senate thanked him publicly, rescinded the decree and reinstated him.[15] The actions of both men intensified the accusations of illegal actions by Cicero and the senate, were seen as a gesture of friendship towards Pompey, and attracted the sympathy of his supporters. Caesar and Nepos forced the senate to play the role of Pompey's opponent and to resort to threaten (in one case) and use (in the other case) a final decree again – the measure whose repressive nature was at the centre of the dispute - thereby exposing it to further charges of tyranny. Public opinion was sensitive to threats to the people's freedom and Cicero's standing deteriorated.[16]

.jpg)

In 62 BC Pompey returned to Italy after winning the Third Mithridatic War against Pontus and Armenia (in present-day eastern Turkey) and annexing Syria. He wanted the senate to ratify the acts of the settlements he had made with the kings and cities in the region en bloc. He was opposed by the optimates led by Lucius Licinius Lucullus, who carried the day in the senate with the support of Cato the Younger.[17] Pompey had taken over the command of the last phase of that war from Lucullus, who felt that he should have been allowed to continue the war and win it. Moreover, when he took over the command of the war Pompey ignored the settlements Lucullus had already made. Lucullus demanded that Pompey should render account for each act individually and separately instead of asking for the approval of all his acts at once in a single vote as if they were the acts of a master. The character of the acts was not known. Each act should be scrutinised, and the senators should ratify those that suited the senate.[18] Appian thought that the optimates, particularly Lucullus, were motivated by jealousy. Crassus cooperated with Lucullus on this matter.[19] Plutarch wrote that when Lucullus returned to Rome after being relieved from his command the senate hoped that it would find in him an opponent of the tyranny of Pompey and a champion of the aristocracy. However, he withdrew from public affairs. Those who looked on the power of Pompey with suspicion made Crassus and Cato the champions of the senatorial party when Lucullus declined the leadership.[20] Plutarch also wrote that Pompey asked the senate to postpone the consular elections so that he could be in Rome to help Marcus Pupius Piso Frugi Calpurnianus to canvass for his candidacy, but Cato swayed the senate to reject this. Plutarch also noted that according to some sources since Cato was the major stumbling block for his ambitions, he asked for the hand of Cato's elder niece for himself and the hand of the younger one, whereas according to other sources he asked for the hand of Cato's daughters. The women were happy with this because of Pompey's high repute, but Cato thought that this was aimed at bribing him by means of a marriage alliance and refused.[21]

In 60 BC, Pompey sponsored an agrarian bill proposed by the plebeian tribune Flavius that provided for distribution of public land. It included land that had been forfeited but not allotted by Lucius Cornelius Sulla when he distributed land to settle his veterans in 80 BC and holdings in Arretium (Arezzo) and Volaterrae (Volterra), both in Etruria. Land was to be purchased with the new revenues from the provinces for the next five years. The optimates opposed the bill because it suspected that 'some novel power for Pompey was aimed at.'[22] They were led by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer, one of the two consuls for that year, who contested every point of the Flavius' bill and 'attacked him so persistently that the latter had him put in prison.' Metellus Celer wanted to convene the senate there and Flavius sat at the entrance of the cell to prevent this. Metellus Celer had the wall cut through to let them in. When Pompey heard this he was afraid about the reaction of the people and told Flavius to desist. Metellus Celer did not consent when the other plebeian tribunes wanted to set him free.[23] The antics of Flavius alienated the people. As time went by they lost interest in the bill and by June the issue was 'completely cold.' Finally, a serious war in Gaul diverted attention from it.[24] Pompey had managed to support the election of Lucius Afranius, who had been one of his commanders in the war in the east, as the other consul. However, he was unfamiliar with political maneuvering. In Cassius Dio's words he "understood how to dance better than to transact any business."[25] In the end, lacking the support of this consul, Pompey let the matter drop.[26] Thus, the Pompeian camp proved inadequate to respond the obstructionism of the optimates.[27]

Accounts of the creation of the alliance

There are several versions of how the alliance came about in the sources.

Appian's version

According to Appian, in 60 BC Caesar came back from his governorship in Hispania (Spain and Portugal) and was awarded a triumph for his victories there. He was making preparations to celebrate this outside the city walls. He also wanted to be a candidate for the consulship for 59 BC. However, the candidates had to present themselves in the city, and it was not legal for those who were preparing a triumph to enter the city and then go back out for these preparations. Since he was not ready yet, Caesar asked to be allowed to register in absentia and to have someone to act on his behalf, even though this was contrary to the law. Cato the Younger, who was against this, used up the last day of the presentation with speeches. Caesar dropped the triumph, entered the city and presented his candidacy. Pompey had failed to get the acts for his settlements he made in the east during the Third Mithridatic War ratified by the senate. Most senators opposed this because they were envious, particularly Lucius Licinius Lucullus who had been replaced in the command of this war by Pompey. Crassus had co-operated with Lucullus in this matter. An aggrieved Pompey ‘made friends with Caesar and promised under oath to support him for the consulship'. Caesar then improved relations between Crassus and Pompey and ‘these three most powerful men pooled their interests.’ Appian also noted that Marcus Terentius Varro wrote a book about this alliance called Tricaranus (the three-headed monster).[28] Appian's version and Plutarch's Life of Pompey are the only sources that have Pompey seeking an alliance with Caesar, rather than the other way round.

Plutarch's version

Plutarch clarified that those who were granted a triumph had to stay outside the city until the celebration, while candidates for the consulship had to be present in the city. The option of registering in absentia through a friend acting on his behalf was turned down and Caesar opted for the consulship. Like Appian, Plutarch wrote that Cato the Younger was the fiercest opponent of Caesar. He steered the other senators towards rejecting the proposal.[29] In both The Life of Cato and The Life of Pompey he wrote that after the agrarian bill was defeated, the hard pressed Pompey resorted to seeking the support of the plebeian tribunes and young adventurers, the worst of whom was Publius Clodius Pulcher (see below). In the former he added that Pompey then won the support of Caesar, who attached himself to him. In the latter he wrote that Caesar pursued a policy of conciliating Crassus and Pompey. Therefore, the two texts seem contradictory.[30] In The Life of Caesar, he wrote that Caesar started his policy to reconcile Pompey and Crassus soon after he entered the city because they were the most influential men. He told them that by concentrating their united strength on him, they could succeed in changing the form of government.[31]

Cassius Dio’s version

In Cassius Dio's account Caesar, who was governor in Hispania in 60 BC, considered his governorship as stepping-stone to the consulship. He left Hispania in a hurry, even before his successor arrived, to get to Rome in time for the elections. He sought the office before holding his triumph as it was too late to celebrate this before the elections. He was refused the triumph through Cato's opposition. Caesar didn't press the matter, thinking that he could celebrate greater exploits if he was elected consul, and so entered the city to canvass for office. He courted Crassus and Pompey so skilfully that he won them over, even though they were still hostile to each other, had their political clubs and ‘each opposed everything that he saw the other wished’.[32]

Suetonius' version

Suetonius' account has Caesar return to Rome from Hispania hastily without even waiting for his successor because he wanted both a triumph and the consulship. As the day of the election for the consulship had already been set, he had to register his candidacy as a private citizen and had to give up his military command and his triumph. When his intrigues to obtain an exemption caused a fuss he gave up the triumph and chose the consulship. There were two other candidates for the consulship, Lucius Lucceius and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus. Caesar made entreaties to the former because he was rich and could treat the electorate with largesse. The aristocracy funded Calpurnius Bibulus for his electoral canvassing because he was a staunch opponent of Caesar, and would keep him in check. Even Cato the Younger, who was a very upright man, "did not deny that bribery under such circumstances was for the good of the republic." Bibulus was elected. Normally the new consuls were assigned important areas of military command, but, in this instance, they were assigned "mere woods and pastures"—another measure intended to blunt Caesar's ambitions. Caesar, angry about 'this slight', tried hard to win over Pompey, who was himself aggrieved at the senate for not ratifying the settlements he made after winning the Third Mithridatic War. Caesar succeeded, patched up the relationship between Crassus and Pompey, and "made a compact with both of them that no step should be taken in public affairs which did not suit any one of the three."[33]

Suetonius's version is the only one that places the creation of the alliance after Caesar was elected. His version is also the only one that mentions the woods and pastures.

Convergence of interests

Ancient sources mention what brought Pompey into the alliance, but are silent on what interests might have brought Crassus into the fold. There are only mentions of Caesar bringing Pompey and Crassus together, which Plutarch described as a reconciliation. Cassius Dio thought that this was something that required skill—almost as if it were a reconciliation of the irreconcilable. In the writings of Suetonius and Plutarch and in some letters and a speech of Cicero, we find clues about both what the interests of Crassus may have been, and indications that Crassus and Pompey might have been less irreconcilable than their portrayals suggest and that the three men of the triumvirate had collaborated before. It could be argued that the formation of the first triumvirate was the result of the marginalisation of an enemy (Caesar) and an outsider (Pompey) and the rebuttal of interests associated with Crassus by the optimates who held sway in the senate.

_-_Glyptothek_-_Munich_-_Germany_2017.jpg)

With respect to the aristocratic circles of the optimates who wanted the supremacy of the senate over Roman politics, Pompey was an outsider. He built his political career as a military commander. He raised three legions in his native Picenum (in central Italy) to support Lucius Cornelius Sulla in retaking Rome, which had been seized by the supporters of Gaius Marius prior to Sulla's second civil war (83–82 BC). Sulla then sent him to Sicily (82 BC) and Africa (81 BC) against the Marians who had fled there, where he defeated them, thereby gaining military glory and distinction, particularly in Africa. Pompey then fought the rebellion by Quintus Sertorius in Hispania from 76 BC to 71 BC during the Sertorian War (80–71 BC). He played a part in the suppression of the slave revolt led by Spartacus (the Third Servile War, 72–70 BC). The latter two earned him the award of a consulship in 70 BC even though he was below the age of eligibility to this office and he had not climbed the cursus honorum, the political career ladder traditionally required to reach the consulship. Pompey was also given the command of a large task force to fight piracy in the Mediterranean Sea by the Gabinian law (67 BC), which gave him extraordinary powers over the whole of the Sea, as well as the lands within 50 miles of its coasts. In 66 BC the Manilian law handed the command of the last phase of the Third Mithridatic War over to Pompey, who brought it to a victorious conclusion.

The political power of Pompey—who spent half of his career up to 63 BC fighting outside Rome—lay outside the conservative aristocratic circles of the optimates. It was based on his popularity as a military commander, political patronage, purchase of votes for his supporters or himself, and the support of his war veterans: "Prestige, wealth, clients, and loyal, grateful veterans who could be readily mobilised – these were the opes which could guarantee [Pompey's] brand of [power]."[34] The opposition of the optimates to the acts of his settlements in the east and the agrarian bill he sponsored were not just due to jealousy as suggested by Appian. The optimates were also weary of the personal political clout of Pompey. They saw him as a potential challenge to the supremacy of the senate, which they largely controlled and which had been criticized for the summary executions during the Catilinarian conspiracy. They saw a politically strong man as a potential tyrant who might overthrow the republic. Pompey remained aloof with regard to the controversies between optimates and populares that raged in Rome at the time when he returned from the Third Mithridatic War in 62 BC. Whilst he did not endorse the populares, he refused to side with the senate, making vague speeches that recognised the authority of the senate, but not acknowledging the principle of senatorial supremacy advocated by Cicero and the optimates.[35]

The opposition to and defeat of the agrarian law sponsored by Pompey was more than just opposition to Pompey. Nor was the law exclusively about allotting land for the settlement of Pompey's veterans, who expected as much ever since Sulla had done likewise in 80 BC. However, the law was framed in a way that the land would be distributed to the landless urban poor as well. This would help to relieve the problem of the mass of the landless unemployed or underemployed poor in Rome, which relied on the provision of a grain dole by the state to survive, and would also make Pompey popular among the plebeians. Populares politicians had been proposing this kind land of reform since the introduction of the agrarian law of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC, which had led to his murder. Attempts to introduce such agrarian laws since then were defeated by the optimates. Thus, the opposition to the bill sponsored by Pompey came within this wider historical context of optimate resistance to reform as well as the optimates being suspicious of Pompey. A crucial element in the defeat of the bill sponsored by Pompey was the fact what the optimates had a strong consul in Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer who vehemently and successfully resisted its enactment, while the consul sponsored by Pompey, Lucius Afranius, was ineffective. The lack of effective consular assistance had been a weakness for Pompey. As already mentioned above, Plutarch wrote that the defeat of the bill forced Pompey to seek the support of the plebeian tribunes, and thus of the populares.[36] With the return of Caesar from his governorship in Hispania, Pompey found a politician who would have the strength and clout to push the bill through if he became consul.

Crassus and Pompey shared a consulship in 70 BC. Plutarch regarded this as having been dull and uneventful because it was marred by continuous disagreement between the two men. He wrote that they "differed on almost every measure, and by their contentiousness rendered their consulship barren politically and without achievement, except that Crassus made a great sacrifice in honour of Hercules and gave the people a great feast and an allowance of grain for three months."[37] The deep enmity during this consulship was also noted by Appian.[38] Plutarch also wrote that Pompey gave the people back their tribunate.[39] This was a reference to the repeal of laws introduced by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 81 BC that had emasculated the power of the plebeian tribunes, by banning it from presenting bills to the vote of the plebeian council and from vetoing the actions of the officers of state and the senatus consulta. He also forbade those who had held this tribunate from running for public office. Sulla had done this because these tribunes had challenged the supremacy of the patrician-controlled senate and he wanted to strengthen the power of the latter. Since these tribunes were the representatives of the majority of the citizens, the people were unhappy with this. Plutarch attributed this repeal to Pompey alone. However, it is very likely that the optimates would have opposed this in the senate, making it unlikely that this measure could have been passed if the two consuls had opposed each other on this issue. Livy’s Periochae (a short summary of Livy's work) recorded that "Marcus Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey were made consuls ... and reconstituted the tribunician powers."[40] Similarly, Suetonius wrote that when Caesar was a military tribune, "he ardently supported the leaders in the attempt to re-establish the authority of the tribunes of the commons [the plebeians], the extent of which Sulla had curtailed."[41] The two leaders must obviously have been the two consuls, Crassus and Pompey. Therefore, on this issue there must have been unity of purpose among these three men. This was an issue of great importance to the populares.

There are indications that Caesar and Crassus may have had significant political links prior to the triumvirate. Suetonius wrote that according to some sources Caesar was suspected with having conspired with Crassus, Publius Sulla, and Lucius Autronius to attack the senate house and kill many senators. Crassus was then to assume the office of dictator and have Caesar named Magister Equitum, reform the state and then restore the consulship to Sulla and Autronius. According to one of the sources from which Suetonius drew this information, Crassus pulled out at the last minute and Caesar did not go ahead with the plan.[42] Plutarch did not mention these episodes in his Life of Caesar. Suetonius wrote that in 65 BC Caesar tried to get command in Egypt assigned to him by the plebeian council when Ptolemy XII, a Roman ally, was deposed by a rebellion in Alexandria, but the optimates blocked the assignment.[43] Plutarch did not mention this either, but in the Life of Crassus he wrote that Crassus, who in that year was a praetor, wanted to make Egypt a tributary of Rome without mentioning the rebellion. He was opposed by his colleague and both voluntarily laid down their offices.[44] Hence there may have been a connection between Crassus' motion and Caesar's ambition.

Plutarch wrote that when Caesar was allocated the governorship of the Roman province of Hispania Ulterior for 60 BC he was in debt and his creditors prevented him from going to his province. Crassus paid off the most intransigent creditors and gave a surety of 830 talents, thereby permitting Caesar to leave. Suetonius noted this episode as well, but did not mention who made the payments and gave the surety.[45] Plutarch thought that Crassus did this because he needed Caesar for his political campaign against Pompey.[46] However, this cannot be taken for granted. In a speech Cicero made against an agrarian bill proposed by the plebeian tribune Publius Servilius Rullus in 63 BC, he claimed that Rullus was an insignificant figure and a front for unsavoury 'machinators' whom he described as the real architects of the bill and as the men who had the real power and who were to be feared. He did not name these men, but he dropped hints that made them identifiable by saying, "Some of them to whom nothing appears sufficient to possess, some to whom nothing seems sufficient to squander." Sumner points out that these were references to the popular images of Crassus and Caesar.[47][48] Thus, it cannot be ruled out that Crassus, Pompey and Caesar might have been willing to cooperate on a specific policy issue on which they agreed, as they had done in 70 BC. Moreover, Caesar had supported the Manilian law of 66 BC, which gave Pompey the command of the final phase of the Third Mithridatic War and, in 63 BC, as noted above, he proposed a motion to recall Pompey to Rome to restore order in the wake of the Catalinarian Conspiracy. Therefore, Caesar was willing to support Pompey because, although the latter was not a popularis, he was not an optimate either, making him a potential ally. Moreover, at the time of the creation of the first triumvirate, Pompey was at odds with the optimates. The suspension of his praetorship in 62 BC by the senate when he advocated the recall of Pompey had probably shown Caesar that his enemies had the means to marginalise him politically. To attain the consulship Caesar needed the support of Pompey and Crassus who, besides being the two most influential men in Rome, did not belong to the optimates and were thus likely to be politically marginalised as well. Plutarch maintained that Caesar sought an alliance with both men because allying with only one of them could have turned the other against him and he thought that he could play them off against each other.[49] However, the picture might have been more nuanced than this.

Crassus may also have had another reason—having to do with the equites—for joining an alliance against the optimates. Cicero noted that in 60 BC Crassus advocated for the equites and induced them to demand that the senate annul some contracts they had taken up in the Roman province of Asia (in today's western Turkey) at an excessive price. The equites (equestrians) were a wealthy class of entrepreneurs who constituted the second social order in Rome, just below the patricians. Many equites were publicani, contractors who acted as suppliers for the army and construction projects (which they also oversaw) and as tax collectors. The state auctioned off the contracts for both suppliers and tax collectors to private firms, which had to pay for them in advance. The publicani had overextended themselves and fell into debt. Cicero thought that these contracts had been taken up in the rush for competition and that the demand was disgraceful and a confession of rash speculation. Nevertheless, he supported the annulment to avoid the equites becoming alienated with the senate and to maintain harmony between patricians and equites. However, his goals were frustrated when the proposal was opposed by the consul Quintus Caecilius Celer and Cato the Younger and subsequently rejected, leading Cicero to conclude that the equites were now at loggerheads with the senate.[50] It has been suggested that Crassus was closely associated with the equites and had investments with them.[51] It is likely that Crassus also saw the alliance with Pompey to ensure Caesar's consulship as a means to pass a measure to relieve publicani in debt.

Caesar’s consulship (59 BC)

.jpg)

With the support of Pompey and Crassus, Caesar was elected consul for 59 BC. The most controversial measure Caesar introduced was an agrarian bill to allot plots of land to the landless poor for farming, which encountered the traditional conservative opposition. In Cassius Dio's opinion, Caesar tried to appear to promote the interests of the optimates as well as those of the people, and said that he would not introduce his land reform if they did not agree with it. He read the draft of the bill to the senate, asked for the opinion of each senator and promised to amend or scrap any clause that had raised objections. The optimates were annoyed because the bill, to their embarrassment, could not be criticised. Moreover, it would give Caesar popularity and power. Even though no optimate spoke against it, no one expressed approval. The law would distribute public and private land to all citizens instead of just Pompey's veterans and would do so without any expense for the city or any loss for the optimates. It would be financed with the proceeds from Pompey's war booty and the new tributes and taxes in the east Pompey established with his victories in the Third Mithridatic War. Private land was to be bought at the price assessed in the tax-lists to ensure fairness. The land commission in charge of the allocations would have twenty members so that it would not be dominated by a clique and so that many men could share the honour. Caesar added that it would be run by the most suitable men, an invitation to the optimates to apply for these posts. He ruled himself out of the commission to avoid suggestions that he proposed the measure out of self-interest and said that he was happy with being just the proposer of the law. The senators kept delaying the vote. Cato advocated the status quo. Caesar came to the point of having him dragged out of the senate house and arrested. Cato said that he was up for this and many senators followed suit and left. Caesar adjourned the session and decided that since the senate was not willing to pass a preliminary decree he would get the plebeian council to vote. He did not convene the senate for the rest of his consulship and proposed motions directly to the plebeian council. Cassius Dio thought Caesar proposed the bill as a favour to Pompey and Crassus.[52]

Appian wrote that the law provided for distribution of public land that was leased to generate public revenues in Campania, especially around Capua, to citizens who had at least three children, and that this included 20,000 men. When many senators opposed the bill, Caesar pretended to be indignant and rushed out of the senate. Appian noted that Caesar did not convene it again for the rest of the year. Instead, he harangued the people and proposed his bills to the plebeian council.[53] Suetonius also mentioned the 20,000 citizens with three children. He also wrote that the allocations concerned land in the plain of Stella (a relatively remote area on the eastern Campanian border) that had been made public in by-gone days, and other public lands in Campania that had not been allotted but were under lease.[54] Plutarch, who had a pro-aristocratic slant, thought that this law was not becoming of a consul, but for a most radical plebeian tribune. Land distribution, which was anathema to conservative aristocrats, was usually proposed by the plebeian tribunes who were often described by Roman writers (who were usually aristocrats) as base and vile. It was opposed by ‘men of the better sort’ (aristocrats) and this gave Caesar an excuse to rush to the plebeian council, claiming that he was driven to it by the obduracy of the senate. It was only the most arrogant plebeian tribunes who courted the favour of the multitude and now Caesar did this to support his consular power 'in a disgraceful and humiliating manner'.[55]

Caesar addressed the people and asked Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, the other consul, if he disapproved of the law. Calpurnius Bibulus just said that he would not tolerate any innovations during his year of office. Caesar did not ask any questions to other officials. Instead he brought forward the two most influential men in Rome, Pompey and Crassus, now private citizens, who both declared their support for the law. Caesar asked Pompey if he would help him against the opponents of the law. Pompey said that he would and Crassus seconded him. Bibulus, supported by three plebeian tribunes, obstructed the vote. When he ran out of excuses for delaying he declared a sacred period for all the remaining days of the year. This meant that the people could not legally even meet in their assembly. Caesar ignored him and set a date for the vote. The senate met at the house of Calpurnius Bibulus because it had not been convened, and decided that Bibulus was to oppose the law so that it would look that the senate was overcome by force, rather than its own inaction. On the day of the vote Bibulus forced his way through the crowd with his followers to the temple of Castor where Caesar was making his speech. When he tried to make a speech he and his followers were pushed down the steps. During the ensuing scuffle, some of the tribunes were wounded. Bibulus defied some men who had daggers, but he was dragged away by his friends. Cato pushed through the crowd and tried to make a speech, but was lifted up and carried away by Caesar's supporters. He made a second attempt, but nobody listened to him.[56][57]

The law was passed. The next day Calpurnius Bibulus tried unsuccessfully to get the senate, now afraid of the strong popular support for the law, to annul it. Bibulus retired to his home and did not appear in public for the rest of his consulship, instead sending notices declaring that it was a sacred period and that this made votes invalid each time Caesar passed a law. The plebeian tribunes who sided with the optimates also stopped performing any public duty. The people took the customary oath of obedience to the law. Cassius Dio wrote that Cato and Quintus Metellus Celer refused to swear compliance. However, on the day when they were to incur the established penalties they took the oath.[58] Appian wrote that many senators refused to take the oath but they relented because Caesar, through the plebeian council, enacted the death penalty for recusants. In Appian's account it is at this point that the Vettius affair occurred.[59]

Appian wrote that Vettius, a plebeian, ran to the forum with a drawn dagger to kill Caesar and Pompey. He was arrested and questioned at the senate house. He said that he had been sent by Calpurnius Bibulus, Cicero, and Cato, and that the dagger was given to him by one of the bodyguards of Calpurnius Bibulus. Caesar took advantage of this to arouse the crowd and postponed further interrogation to the next day. However, Vettius was killed in prison during the night. Caesar claimed that he was killed by the optimates who did not want to be exposed. The crowd gave Caesar a bodyguard. According to Appian, it is at this point that Bibulus withdrew from public business and did not go out of his house for the rest of his term of office. Caesar, who ran public affairs on his own, did not make any further investigations into this affair.[60] In Cassius Dio's version, Vettius was sent by Cicero and Lucullus. He did not say when this happened and did not give any details about the actual event. He wrote that Vettius accused these two men and Calpurnius Bibulus. However, Bibulus had revealed the plan to Pompey, which undermined Vettius' credibility. There were suspicions that he was lying about Cicero and Lucullus as well and that this was a ploy by Caesar and Pompey to discredit the optimates. There were various theories, but nothing was proven. After naming the mentioned men in public, Vettius was sent to prison and was murdered a little later. Caesar and Pompey suspected Cicero and their suspicions were confirmed by his defence of Gaius Antonius Hybrida in a trial.[61]

Other writers blamed either Pompey or Caesar. Plutarch did not indicate when the incident happened either. In his version it was a ploy by the supporters of Pompey, who claimed that Vettius was plotting to kill Pompey. When questioned in the senate he accused several people, but when he spoke in front of the people, he said that Licinius Lucullus was the one who arranged the plot. No one believed him and it was clear that the supporters of Pompey got him to make false accusations. The deceit became even more obvious when he was battered to death a few days later. The opinion was that he was killed by those who had hired him.[62] Suetonius wrote that Caesar had bribed Vettius to tell a story about a conspiracy to murder Pompey according to a prearranged plot, but he was suspected of ‘double-dealing.’ He also wrote that Caesar was supposed to have poisoned him.[63] Cicero gave an account in some letters to his friend Atticus. Vettius, an informer, claimed that he had told Curio Minor that he had decided to use his slaves to assassinate Pompey. Curio told his father Gaius Scribonius Curio, who in turn told Pompey. When questioned in the senate he said that there was a group of conspiratorial young men led by Curio. The secretary of Calpurnius Bibulus gave him a dagger from Bibulus. He was to attack Pompey at the forum at some gladiatorial games and the ringleader for this was Aemilius Paullus. However, Aemilius Paullus was in Greece at the time. He also said that he had warned Pompey about the danger of plots. Vettius was arrested for confessing to possession of a dagger. The next day Caesar brought him to the rosta (a platform for public speeches), where Vettius did not mention Curio, implicating other men instead. Cicero thought that Vettius had been briefed on what to say during the night, given that the men he mentioned had not previously been under suspicion. Cicero noted that it was thought that this was a setup and that the plan had been to catch Vettius in the forum with a dagger and his slaves with weapons, and that he was then to give information. He also thought that this had been masterminded by Caesar, who got Vettius to get close to Curio.[64][65]

According to Cassius Dio, Cicero and Lucullus plotted to murder Caesar and Pompey because they were not happy with some steps they had taken. Fearing that Pompey might take charge in Rome while Caesar was away for his governorships (see below), Caesar tied Pompey to himself by marrying him to his daughter Julia even though she was betrothed to another man. He also married the daughter of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, one for the consuls elected for the next year (58 BC). Appian wrote that Cato said that Rome had become a mere matrimonial agency. These marriages were also mentioned by Plutarch and Suetonius.[66][67][68]

Caesar proceeded to pass a number of laws without opposition. The first was designed to relieve the publicani from a third of their debt to the treasury (see previous section for details about the publicani). Cassius Dio noted that the equites often had asked for a relief measure to no avail because of opposition by the senate and, in particular, by Cato.[69] Since the publicani were mostly equites Caesar gained the favour of this influential group. Appian wrote that the equites ‘extolled Caesar to the skies’ and that a more powerful group than that of the plebeians was added to Caesar's support.[70] Caesar also ratified the acts of Pompey's settlements in the east, again, without opposition, not even by Licinius Lucullus. Caesar's influence eclipsed that of Calpurnius Bibulus, with some people suppressing the latter's name in speaking or writing and stating that the consuls were Gaius Caesar and Julius Caesar. The plebeian council granted him the governorship of Illyricum and Cisalpine Gaul with three legions for five years. The senate granted him the governorship of Transalpine Gaul and another legion (when the governor of that province died) because it feared that if it refused this the people would also grant this to Caesar.[71][72][73][74]

Cassius Dio wrote that Caesar secretly set Publius Clodius Pulcher against Cicero, whom he considered a dangerous enemy, because of his suspicions about the Vettius affair. Caesar believed that Clodius owed him a favour in return for not testifying against him when he was tried for sacrilege three years earlier (see above).[75] However, Clodius did not need to owe anything to Caesar to attack Cicero: he already bore a grudge against him because he had testified against him at this trial. In another passage Cassius Dio wrote that after the trial Clodius hated the optimates.[76] Suetonius described Clodius as the enemy of Cicero.[77] Appian wrote that Clodius had already requited Caesar by helping him to secure the governorship of Gaul before Caesar unleashed him against Cicero and that Caesar ‘turned a private grievance to useful account’.[78] Moreover, Clodius was already an ally of Pompey before this. As mentioned in the previous section, Plutarch wrote that Pompey had already allied with Clodius when his attempt to have the acts for his settlements in the east failed before the creation of the triumvirate.[79]

Clodius sought to become a plebeian tribune so that he could enjoy the powers of these tribunes to pursue his revenge against Cicero, including presiding over the plebeian council, proposing bills to its vote, vetoing the actions of the officers of state and the senatus consulta (written opinions of the senate on bills, which were presented for advice and usually followed to the letter). However, Clodius was a patrician and the plebeian tribunate was exclusively for plebeians. Therefore, he needed to be transferred to the plebeian order (transitio ad plebem) by being adopted into a plebeian family. In some letters written in 62 BC, the year after Clodius's trial, Cicero wrote that Herrenius, a plebeian tribune, made frequent proposals to the plebeian council to transfer Clodius to the plebs, but he was vetoed by many of his colleagues. He also proposed a law to the plebeian council to authorise the comitia centuriata (the assembly of the soldiers) to vote on the matter. The consul Quintus Metellus Celer proposed an identical bill to the comitia centuriata.[80] Later in the year, Cicero wrote that Metellus Celer was ‘offering Clodius ‘a splendid opposition’. The whole senate rejected it.[81] Cassius Dio, instead, wrote that in that year Clodius actually got his transitio ad plebem and immediately sought the tribunate. However, he was not elected due to the opposition of Metellus Celer, who argued that his transitio ad plebem was not done according to the lex curiata, which provided that adrogatio should be performed in the comitia curiata. Cassius Dio wrote that this ended the episode. During his consulship Caesar effected this transitio ad plebem and had him elected as plebeian tribune with the cooperation of Pompey. Clodius silenced Calpurnius Bibulus when he wanted to make a speech on the last day of his consulship in 59 BC and also attacked Cicero.[82]

Events in 58 BC and 57 BC

Early in 58 BC Clodius proposed four laws. One re-established the legitimacy of the collegia; one made the state-funded grain dole for the poor completely free for the first time (previously it was at subsidised prices); one limited the remit of bans on the gatherings of the popular assemblies; and one limited the power of the censors to censor citizens who had not been previously tried and convicted. Cassius Dio thought that the aim of these laws was to gain the favour of the people, the equites and the senate before moving to crush the influential Cicero. Then he proposed a law that banned officials from performing augury (the divination of the omens of the gods) on the day of the vote by the popular assemblies, with the aim of preventing votes from being delayed. Officials often announced that they would perform augury on the day of the vote because during this voting was not allowed and this forced its postponement. In Cassius Dio's opinion, Clodius wanted to bring Cicero to trial and did not want the voting for the verdict delayed.[83]

Cicero understood what was going on and got Lucius Ninnius Quadratus, a plebeian tribune, to oppose every move of Clodius. The latter, fearing that this could result in disturbances and delays, outwitted them by deceit, agreeing with Cicero not to bring an indictment against him. However, when these two men lowered their guard, Clodius proposed a bill to outlaw those who would or had executed any citizen without trial. This brought within its scope the whole of the senate, which had decreed the executions during the Catilinarian conspiracy of 63 BC (see above). Of course, the actual target was Cicero, who had received most of the blame because he had proposed the motion and had ordered the executions. Cicero strenuously opposed the bill. He also sought the support of Pompey and Caesar, who were secretly supporting Clodius, a fact they went to some pains to conceal from Cicero. Caesar advised Cicero to leave Rome because his life was in danger and offered him a post as one of his lieutenants in Gaul so that his departure would not be dishonourable. Pompey advised him that to leave would be an act of desertion and that he should remain in Rome, defend himself and challenge Clodius, who would be rendered ineffective in the face of Pompey and Cicero's combined opposition. He also said that Caesar was giving him bad advice out of enmity. Pompey and Caesar presented opposite views on purpose to deceive Cicero and allay any suspicions. Cicero attached himself to Pompey, and also thought that he could count on the consuls. Aulus Gabinius was a friend of his and Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus was amiable and a kin of Caesar.[84][85]

The equites and two senators, Quintus Hortensius and Gaius Scribonius Curio, supported Cicero. They assembled on the Capitol and sent envoys to the consuls and the senate on his behalf. Lucius Ninnius tried to rally popular support, but Clodius prevented him from taking any action. Aulus Gabinius barred the equites from accessing the senate, drove one of the more persistent out of the city, and rebuked Quintus Hortensius and Gaius Curio. Calpurnius Piso advised Cicero that leaving Rome was the only way for him to be safe, at which Cicero took offence. Caesar condemned the illegality of the action taken in 63 BC, but did not approve the punishment proposed by the law because it was not fitting for any law to deal with past events. Crassus had shown some support through his son, but he sided with the people. Pompey promised help, but he kept making excuses and taking trips out of Rome. Cicero, unnerved by the situation, considered resorting to arms and slighted Pompey openly. However, he was stopped by Cato and Hortensius, who feared a civil war. Cicero then left for Sicily, where he had been a governor, hoping to find sympathy there. On that day the law was passed without opposition, being supported even by people who had actively helped Cicero. His property was confiscated and his house was demolished. Then Clodius carried a law that banned Cicero from a radius of 500 miles from Rome and provided that both he and those who harboured him could be killed with impunity. As a result of this, he went to Greece.[86]

However, Cicero's exile lasted only sixteen months (April 58 – August 57 BC).[87][88] Pompey, who had engineered his exile, later wanted to have him recalled, because Clodius had taken a bribe to free Tigranes the Younger, one of Pompey‘s prisoners from the Third Mithridatic War. When Pompey and Aulus Gabinius remonstrated, he insulted them and came into conflict with their followers. Pompey was annoyed because the authority of the plebeian tribunes, which he had restored in 70 BC (see above) was now being used against him by Clodius.[89] Plutarch wrote that when Pompey went to the forum a servant of Clodius went towards him with a sword in his hand. Pompey left and did not return to the forum while Clodius was a tribune (Plutarch must have meant except for public business as Pompey did attend sessions of the senate and the plebeian council, which were held in the northern area of the forum). He stayed at home and conferred about how to appease the senate and the nobility. He was urged to divorce Julia and switch allegiance from Caesar to the senate. He rejected this proposal, but agreed with ending Cicero's exile. So, he escorted Cicero's brother to the forum with a large escort to lodge the recall petition. There was another violent clash with casualties, but Pompey got the better of it.[90] Pompey got Ninnius to work on Cicero's recall by introducing a motion in Cicero's favour in the senate and opposing Clodius ‘at every point’. Titus Annius Milo, another plebeian tribune, presented the measure to the plebeian council and Publius Cornelius Lentulus Spinther, one of the consuls for 57 BC, provided support in the senate partly as a favour to Pompey and partly because of his enmity towards Clodius. Clodius was supported by his brother Appius Claudius, who was a praetor, and the other consul, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos who had opposed Cicero six years earlier (see above). Pro-Cicero and pro-Clodius factions developed, leading to violence between the two. On the day of the vote, Clodius attacked the assembled people with gladiators, resulting in casualties, and the bill was not passed. Milo indicted the fearsome Clodius for the violence, but Metellus Nepos prevented this. Milo started using gladiators, too, and there was bloodshed around the city. Metellus Nepos, under pressure from Pompey and Lentulus Spinther, changed his mind. The senate decreed Spinther's motion for the recall of Cicero and both consuls proposed it to the plebeian council, which passed it.[91] Appian wrote that Pompey gave Milo hope that he would become consul, set him against Clodius and got him to call for a vote for the recall. He hoped that Cicero would then no longer speak against the triumvirate.[92]

When Cicero returned to Rome, he reconciled with Pompey, at a time when popular discontent with the Senate was high due to food shortages. When the people began to make death threats, Cicero persuaded them pass a law to elect Pompey as praefectus annonae (prefect of the provisions) in Italy and beyond for five years. This post was instituted at times of severe grain shortage to supervise the grain supply. Clodius alleged that the scarcity of rain had been engineered to propose a law that boosted Pompey's power, which had been decreasing. Plutarch noted that others said that it was a device by Lentulus Spinther to confine Pompey to an office so that Spinther would be sent instead to Egypt to help Ptolemy XII of Egypt put down a rebellion. A plebeian tribune had proposed a law to send Pompey to Egypt as a mediator without an army, but the senate rejected it, citing safety concerns. As praefectus annonae Pompey sent agents and friends to various places and sailed to Sardinia, Sicily and the Roman province of Africa (the breadbaskets of the Roman empire) to collect grain. So successful was this venture that the markets were filled and there was also enough to supply foreign peoples. Both Plutarch and Cassius Dio thought that the law made Pompey ‘the master of all the land and sea under Roman possession’. Appian wrote that this success gave Pompey great reputation and power. Cassius Dio also wrote that Pompey faced some delays in the distribution of grain because many slaves had been freed prior to the distribution and Pompey wanted to take a census to ensure they received it in an orderly way.[93][94][95]

Having escaped prosecution, Clodius attained the aedileship for 57 BC. He then started proceedings against Milo for inciting violence, the same charge Milo had brought against him. He did not expect a conviction, as Milo had many powerful allies, including Cicero and Pompey. He used this to attack both his followers and Pompey, inciting his supporters to taunt Pompey in the assemblies, which the latter was powerless to stop. He also continued his attacks on Cicero. The latter claimed that his transitio ad plebem was illegal and so were the laws he had passed, including the one that sanctioned his exile. And so clashes between the two factions continued.[96]

Luca conference and subsequent events

In 56 BC Caesar, who was fighting the Gallic Wars, crossed the Alps into Italy and wintered in Luca (Lucca, Tuscany). In the Life of Crassus, Plutarch wrote that a big crowd wanted to see him and 200 men of senatorial rank and various high officials turned up. He met Pompey and Crassus and agreed that the two of them would stand for the consulship and that he would support them by sending soldiers to Rome to vote for them. They were then to secure the command of provinces and armies for themselves and confirm his provinces for a further five years. Therefore, he worked on putting the officials of the year under his obligation. In the Life of Pompey, Plutarch added that Caesar also wrote letters to his friends and that the three men were aiming at making themselves the masters of the state.[97] Suetonius maintained that Caesar compelled Pompey and Crassus to meet him at Luca. This was because Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, one of the praetors, called for an inquiry into his conduct in the previous year. Caesar went to Rome and put the matter before the senate, but this was not taken up and he returned to Gaul. He was also a target for prosecution by a plebeian tribune, but he was not brought to trial because he pleaded with the other tribunes not to prosecute him on the grounds of his absence from Rome. Lucius Domitius was now a candidate for the consulship and openly threatened to take up arms against him. Caesar prevailed on Pompey and Crassus to stand for the consulship against Lucius Domitius. He succeeded through their influence to have his term as governor of Gaul extended for five years.[98] In Appian's account, too, 200 senators went to see Caesar, as did many incumbent officials, governors and commanders. They thanked him for gifts they received or asked for money or favours. Caesar, Pompey and Crassus agreed on the consulship of the latter two and the extension of Caesar's governorship. In this version Lucius Domitius presented his candidacy for the consulship after Luca and did so against Pompey.[99]

Cassius Dio, who wrote the most detailed account of the period, did not mention the Luca conference. In his version, instead, Pompey and Crassus agreed to stand for the consulship between themselves as a counterpoise to Caesar. Pompey was annoyed about the increasing admiration of Caesar due to his success in the Gallic Wars, feeling that this was overshadowing his own exploits. He tried to persuade the consuls not to read Caesar's reports from Gaul and to send someone to relieve his command. He was unable to achieve anything through the consuls and felt that Caesar no longer needed him. Believing himself to be in a precarious situation and thus unable to challenge Caesar on his own, Pompey began to arm himself and got closer to Crassus. The two men decided to stand for the consulship to tip the balance of power in their favor. So, they gave up their pretence that they did not want to take the office and begun canvassing, although outside the legally specified period. The consuls said that there would not be any elections that year and that they would appoint an interrex to preside over the elections in the next year so that they would have to seek election in accordance with the law. There was a lot of wrangling in the senate and the senators left the session. Cato, who in that year was a plebeian tribune, called people from the forum into the senate house because voting was not allowed in the presence of non-senators. However, other plebeian tribunes prevented the outsiders from getting in. The decree was passed. Another decree was opposed by Cato. The senators left and went to the forum and one of them, Marcellinus, presented their complaints to the people. Clodius took Pompey's side again to get his support for his aims, addressed the people, inveighing against Marcellinus, and then went to the senate house. The senators prevented him from entering and he was nearly lynched. He called out for the people to help him and some people threatened to torch the senate house. Later Pompey and Crassus were elected consuls without any opposing candidates apart from Lucius Domitius. One of the slaves who was accompanying him in the forum was killed. Fearing for his own safety, Clodius withdrew his candidacy. Publius Crassus, a son of Crassus who was one of Caesar's lieutenants, brought soldiers to Rome for intimidation.[100]

In the Life of Crassus, Plutarch wrote that in Rome there were reports about the two men's meeting with Caesar. Pompey and Crassus were asked if they were going to be candidates for the consulship. Pompey replied that perhaps he was, and perhaps he was not. Crassus replied that he would if it was in the interest of the city, but otherwise he would desist. When they announced their candidacies everyone withdrew theirs, but Cato encouraged Lucius Domitius to proceed with his. He withdrew it when his slave was killed. Plutarch mentioned Cato's encouragement and the murder of the slave in The Life of Pompey as well.[101]

In Cassius Dio's account after the election Pompey and Crassus did not state what their intentions were and pretended that they wanted nothing further. Gaius Trebonius, a plebeian tribune, proposed a measure that gave the province of Syria and the nearby lands to one of the consuls and the provinces of Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior to the other. They would hold the command there for five years. They could levy as many troops as they wanted and ‘make peace and war with whomsoever they pleased’. According to Cassius Dio, who held that Crassus and Pompey wanted to counter Caesar's power, many people were angry about this, especially Caesar's supporters, who felt that Pompey and Crassus wanted to restrict Caesar's power and remove him from his governorship. Therefore, Crassus and Pompey extended Caesar's command in Gaul for three years. Cassius Dio stated that this was the actual fact, which implies that he disagreed with the notion that his command was extended for five years. With Caesar's supporters appeased, Pompey and Crassus made this public only when their own arrangements were confirmed.[102] In The Life of Pompey, Plutarch wrote the laws proposed by Trebonius were in accordance with the agreement made at Luca. They gave Caesar's command a second five-year term, assigned the province of Syria and an expedition against Parthia to Crassus and gave Pompey the two provinces in Hispania (where there had recently been disturbances[103]), the whole of Africa (presumably Plutarch meant Cyrenaica as well as the province of Africa) and four legions. Pompey lent two of these legions to Caesar for his wars in Gaul at his request.[104] According to Appian Pompey lent Caesar only one legion. This was when Lucius Aurunculeius Cotta and Quintus Titurius Sabinus, two of Caesar's lieutenants, were defeated in Gaul by Ambiorix in 54 BC.[105]

Two plebeian tribunes, Favonius and Cato, led the opposition to the steps of the consuls. However, they did not get far, due to popular support for the measures. Favonius was given little time to speak before the plebeian council, and Cato applied obstructionist tactics that did not work. He was led away from the assembly, but he kept returning and he was eventually arrested. Gallus, a senator, slept in the senate house intending to join the proceedings in the morning. Trebonius locked the doors and kept him there for most of the day. The comitia (the meeting place of the assembly) was blocked by a cordon of men. An attempt to pass through was repulsed violently and there were casualties. When people were leaving after the vote, Gallus, who had been let out of the senate house, was hit when he tried to pass through the cordon. He was presented covered with blood to the crowd, which caused general upset. The consuls stepped in with a large and intimidating bodyguard, called a meeting and passed the measure in favour of Caesar.[106][107]

Pompey and Crassus conducted the levy for their campaigns in their provinces, which created discontent. Some of the plebeian tribunes instituted a suit nominally against Pompey's and Crassus' lieutenants that was actually aimed at them personally. The tribunes then tried to annul levies and rescind the vote for the proposed campaigns. Pompey was not perturbed because had already sent his lieutenants to Hispania. He had intended to let them deal with Hispania while he would gladly stay in Rome with the pretext that he had to stay there because he was the praefectus annonae. Crassus, on the other hand, needed his levy for his campaign against Parthia, and so he considered using force against the tribunes. The unarmed plebeian tribunes avoided a violent confrontation, but they did criticise him. While Crassus was offering the prayers, which were customary before war, they claimed bad omens. One of the tribunes tried to have Crassus arrested. However, the others objected and while they were arguing, Crassus left the city. He then headed for Syria and invaded Parthia.[108] Plutarch thought that Crassus, the richest man in Rome, felt inferior to Pompey and Caesar only in military achievement and added a passion for glory to his greed. His achievements in the Battle of the Colline Gate (82 BC) and in the Third Servile War (71 BC) were now a fading memory. Plutarch also wrote that Caesar wrote to Crassus from Gaul, approving of his intentions and spurring him to war.[109]

End of the triumvirate (53 BC)

In 54 BC, as Caesar continued his campaigns in Gaul and Crassus undertook his campaign against the Parthians, Pompey was the only member of the triumvirate left in Rome. Because Cicero, grateful for his recall, no longer opposed Pompey, Cato became the triumvirate's main opponent. With bribery and corruption rampant throughout the Republic, Cato, who was elected praetor for 54 BC, got the senate to decree that elected officials submit their accounts to a court for scrutiny of their expenditures for electoral canvassing. This aggrieved both the men in question and the people (who were given money for votes). Cato was attacked by a crowd during a court hearing, but managed to bring the disturbance to an end with a speech. Cato then monitored the subsequent elections against misconduct after an agreement on electoral practices, which made him popular. Pompey considered this a dilution of his power and set his supporters against Cato. This included Clodius, who had joined Pompey's fold again.[110]

In September 54 BC, Julia, the daughter of Caesar and wife of Pompey, died while giving birth to a girl, who also died a few days later.[111][112] Plutarch wrote that Caesar felt that this was the end of his good relationship with Pompey. The prospect of a breach between Caesar and Pompey created unrest in Rome. The campaign of Crassus against Parthia was disastrous. Shortly after the death of Julia, Crassus died at the Battle of Carrhae (May 53 BC), bringing the first triumvirate to an end. Plutarch thought that fear of Crassus had led to Pompey and Caesar to be decent to each other, and his death paved the way for the subsequent friction between these two men and the events that eventually led to civil war.[113] Florus wrote: "Caesar's power now inspired the envy of Pompey, while Pompey's eminence was offensive to Caesar; Pompey could not brook an equal or Caesar a superior."[114] Seneca wrote that with regard to Caesar, Pompey "would ill endure that anyone besides himself should become a great power in the state, and one who was likely to place a check upon his advancement, which he had regarded as onerous even when each gained by the other's rise: yet within three days' time he resumed his duties as general, and conquered his grief [for the death of his wife] as quickly as he was wont to conquer everything else."[115]

In the Life of Pompey, Plutarch wrote that the plebeian tribune Lucilius proposed to elect Pompey dictator, which Cato opposed. Lucilius came close to losing his tribunate. Despite all this, two consuls for the next year (53 BC) were elected as usual. In 53 BC three candidates stood for the consulship for 52 BC. Besides resorting to bribery, they promoted factional violence, which Plutarch saw as a civil war. There were renewed and stronger calls for a dictator. However, in the Life of Cato, Plutarch did not mention any calls for a dictator and instead he wrote that there were calls for Pompey to preside over the elections, which Cato opposed. In both versions, the violence among the three factions continued and the elections could not be held. The optimates favoured entrusting Pompey with restoring order. Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, the former enemy of the triumvirate, proposed in the senate that Pompey should be elected as sole consul. Cato changed his mind and supported this on the ground that any government was better than no government. Pompey asked him to become his adviser and associate in governance, and Cato replied that he would do so in a private capacity.[116]

Pompey married Cornelia, a daughter of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio. Some people disliked this because Cornelia was much younger and she would have been a better match for his sons. There were also people who thought that Pompey gave priority to his wedding over dealing with the crisis in the city. Pompey was also seen as being partial in the conduct of some trials. He succeeded in restoring order and chose his father-in‑law as his colleague for the last five months of the year. Pompey was granted an extension of his command in his provinces and was given an annual sum for the maintenance of his troops. Cato warned Pompey about Caesar's manoeuvres to increase his power by using the money he made from the spoils of war to extend is patronage in Rome and urged him to counter Caesar. Pompey hesitated, and Cato stood for the consulship in order to deprive Caesar of his military command and have him tried. However, he was not elected.

The supporters of Caesar argued that Caesar deserved an extension of his command so that the fruits of his success would not be lost. During the ensuing debate, Pompey showed goodwill towards Caesar. He claimed that he had letters from Caesar in which he said he wanted to be relieved of his command, but he said that he thought that he should be allowed to stand for the consulship in absentia. Cato opposed this and said that if Caesar wanted this he had to lay down his arms and become a private citizen. Pompey did not contest Cato's proposal, which gave rise to suspicions about his real feelings towards Caesar. Plutarch wrote that Pompey also asked Caesar for the troops he had lent him back, using the Parthian war as a pretext. Although Caesar knew why Pompey asked this, he sent the troops back home with generous gifts. Appian wrote that Caesar gave these soldiers a donation and also sent one of his legions to Rome.[117] Pompey was drifting toward the optimates and away from Caesar. According to Plutarch the rift between Pompey and Cato was exacerbated when Pompey fell seriously ill in Naples in 50 BC. When he recovered the people of Naples offered thanksgiving sacrifices. This celebration spread throughout Italy, as he was feted in towns through which he traveled on his way back to Rome. Plutarch wrote that this was said ‘to have done more than anything else to bring about the subsequent civil war’. It made Pompey arrogant, incautious and contemptuous of Caesar's power.[118] The following year the two men were fighting each other in the Great Roman Civil War.

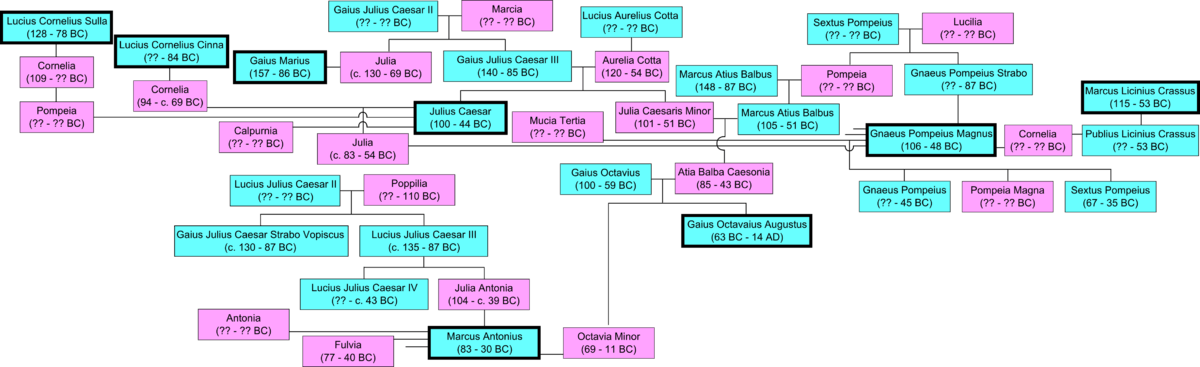

Family tree

See also

- Constitution of the Roman Republic – The norms, customs, and written laws, which guided the government of the Roman Republic

- Triumvirate

- Assassination of Julius Caesar – Stabbing attack that caused the death of Julius Caesar

Notes

- Sallust, The War with Catiline, 18.3

- Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 10.3

- Cicero, Pro Caelio IV

- Cicero, Commentariolum Petitionis, 3

- Tatum, J. W., The final Crisis (69–44), p.195

- Sallust, The War with Catiline, 24.3

- In a letter to Catullus, Catiline wrote: "I have pursued a course of action that offers hope of preserving of what remains of my prestige (dignitas)" Sallust, The War with Catiline, 35.4

- Senatus consultum ultimum in modern terminology, senatus consultum de res publica defendenda, (decree of the Senate about defending the Republic) in the terminology used by the Romans.

- Tatum, J. W., The final Crisis (69–44), p.195-6

- Sallust, The War with Catiline,20–61

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.42

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The life of Cato the younger, 27–29.1–2

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.43

- Tatum, J. W., The final Crisis (69–44), p.198

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 16

- Mitchell, T. N., Cicero, Pompey, and the Rise of the First Triumvirate, Traditio, Vol. 29 (1973), pp. 3–7

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Pompey, 49.3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.49, 50.1

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.9

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, the Life of Lucullus, 38.2, 42.5

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, the Life of Cato Minor, 30.1–4, The Life of Pompey, 44.2–3

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 1.19.4

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.49

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 1.19.4

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 37.49.3

- Tatum, J. W., The final Crisis (69–44), p.198

- Mitchell, T. N., Cicero, Pompey, and the Rise of the First Triumvirate, pp. 19–20

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.8–9

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Live of Caesar, 13.1–2

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Cato Minor, 31.2, 4, The Life of Pompey, 46.4, 47.1

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Caesar, 13.3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.54

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 19.2

- Mitchell, T., Cicero, Pompey and the rise of the First Triumvirate, Traditio, Vol. 29 (1973), p. 17

- Mitchell, T., Cicero, Pompey and the rise of the First Triumvirate, Traditio, Vol. 29 (1973), p. 17

- Plutarch Parallel Lives, The Life of Pompey, 46.4

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Crassus, 12.2

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 1.121

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Live of Pompey, 21–23.1–2

- Livy Periochae, 97.6

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 5

- Suetonius The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 9

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar,11

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Crassus, 13.1

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar,18.1

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Caesar, 11.1–2

- Cicero, On the Agrarian Laws, 2.65

- G. V. Sumner, Cicero, Pompeius, and Rullus, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 97 (1966), p. 573

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Caesar,

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 1.17.9, 2.1.8

- Badian, E., Publicans and Sinners; Private Enterprise in the Service of the Roman Republic, pp.103–104

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 2.1–4.1

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.10

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 30.3

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The life of Caesar, 14.2–3; The Live of Cato Minor, 31-5-32.1

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 38.4–7.6

- Appian, The Civil Wars 2.11–12

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 6.4–6, 7

- Appian, The Civil wars, 2.12

- Appian, The Civil Wars 2.12

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 38.9

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Lucullus, 42.7

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, The life of Julius Caesar, 20.5

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 2.24

- Stockton, D., Cicero: A Political Biography, pp. 183–86

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.14

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, the Live of Caesar. 17.7, The Life of Pompey, 47.6

- Suetonius, The twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 21

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 38. 6.4

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.13

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 2.7.5; 8.2, 5

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.13

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 22.1

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The life of Caesar, 14.10

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 38.12.1

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.51.1

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar 21.4

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.14

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Pompey, 46.3

- Roman adoption was ratified by two different ceremonies, adoptio and adrogatio. The former was for men were under the authority of their fathers (patria potestas). The latter was for men who were sui juris (of one's own right)--that is, not under patria potestas. Adrogatio, which applied to Clodius because his father had died, had to be performed by the comitia curiata. Clodius wanted to transfer adrogatio from the comitia curiata to the comitia centuriata. Cicero suggested that he wanted to submit his adoption to the vote of the people (he said the law was to authorise the whole people to vote on his adoption). The comitia centuriata was a voting body, whereas the comitia curiata was only a ceremonial body.

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 1.18.51–52, 1.19.55, 2.1.4; On the Responses of the Haruspices, 45

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 37.51.1–2; 38.12.1–3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 38.12.4–5, 13

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39-14-16.1

- Grillo., L., Cicero’s De Provinciis Consularibus Oratio (2015), p. 3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.16.2-6-18.1

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.16

- Grillo., L., Cicero’s De Provinciis Consularibus Oratio (2015), p. 3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 38.30.1–3

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Pompey, 49.1–3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 38.30.3–4, 39.6–8

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.16

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Pompey, 49.4–6, 50

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.9. 24.1–2

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.18

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.18–20.3, 21

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Live of Pompey, 51.3–6; The Life of Crassus, 14. 4–6

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Julius Caesar, 23, 24.1

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.17

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.24.14, 25.1–4,28.1–4, 26–30.1–3, 31

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Crassus, 15, The Life of Pompey, 51.4–6

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.33

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.33.2

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Live of Pompey, 52.3

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.29, 33.2

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.34–36

- Plutarch, The Life of Cato Minor, 43.1–3

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, 39.39

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Crassus, 14.4, 16.3

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Cato Minor, 44.1–4, 45

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 39.64.1

- Appian, The Civil Wars 2.19

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Live of Caesar 23.5–6; The Live of Pompey, 53.4–6

- Florus, Epitome of Roman History, 2.13.14

- Seneca, Dialogues, Book 6, Of Consolation: To Marcia, 6.14.3

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, the Life of Pompey, 54; The Life of Cato Minor, 47–49

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.29

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Cato Minor, 49, The Life of Pompey, 54.5-6-57

References

- Primary sources