Battle of Bairoko

The Battle of Bairoko was fought between American and Imperial Japanese Army and Navy forces on 20 July 1943 on the northern coast of New Georgia island. Taking place during World War II, it formed part of the New Georgia campaign of the Pacific War. In the battle, two battalions of the U.S. Marine Raiders from the 1st Marine Raider Regiment, supported by two U.S. Army infantry battalions attacked a Japanese garrison guarding the port of Bairoko on the Dragons Peninsula, advancing from Enogai and Triri. After a day long engagement, the Japanese repulsed the American assault and forced the attacking troops to withdraw with their wounded to Enogai. US forces remained in the area carrying out patrolling and intelligence gathering operations until the end of the campaign. Bairoko was eventually captured at the end of August after the airfield at Munda had been captured, and further reinforcements sent from there towards Bairoko to clear the area from the south.

Background

Strategic situation

Following the completion of the Guadalcanal campaign in early 1943, the Allied high command began planning the next step in their effort to neutralize the main Japanese base at Rabaul as part of Operation Cartwheel. The advance north through the central Solomon Islands involved a series of operations to secure island bases for shipping and aircraft. Plans for 1943 conceived the capture of New Georgia and then later Bougainville by US troops. Elsewhere, in New Guinea, the Australians would capture Lae and Salamaua and secure Finschhafen.[2][3]

The campaign to secure New Georgia, designated Operation Toenails by US planners, was focused upon securing the airfield at Munda Point, on the western coast of New Georgia island. As part of this effort, several initial landings were undertaken to capture staging areas at Wickham Anchorage and Viru Harbor and an airfield at Segi Point in the southern part of New Georgia, to support the movement of troops and supplies from Guadalcanal. These supplies would be staged through to Rendova, which would be built up as base for further operations in New Georgia focused on securing the airfield at Munda. These preliminary operations began at the end of June 1943.[4][5]

Opposing forces

In the fighting around the port of Bairoko, a total of four American battalions were committed. The main attacking force consisted of two battalions of the U.S. Marine Raiders from the 1st Marine Raider Regiment (the 1st and 4th Battalions). Both battalions had been depleted by previous actions; the 1st around Enogai and the 4th in southern New Georgia. The Marines were supported by two U.S. Army infantry battalions (the 3rd Battalion, 145th Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry Regiment).[6][7] Equipped for light maneuver, no artillery had been provided. The Marines lacked heavy weapons, although the two U.S. Army battalions possessed heavy mortars and machine guns. Air support was available, but was unreliable.[8][9] The US troops were commanded by Colonel Harry B. Liversedge.[10]

Japanese forces had arrived around Enogai and Bairoko, on the Dragons Peninsula, in March 1942, as part of an effort to secure airbases on New Georgia to support their operations on Guadalcanal.[11] Prior to the attack, US intelligence had estimated that Japanese forces in the Bairoko area numbered only 500 troops; in reality at the time of the US attack on Bairoko there were about 300 Japanese soldiers and 800 naval personnel in the area, making a total of 1,100.[12] The main Japanese unit holding Bairoko was Colonel Saburo Okumura's Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force; these were reinforced by elements of the 2nd Battalion, 13th Infantry Regiment.[13] On 13 July, part of the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry Regiment, and a battery from the 6th Field Artillery Regiment arrived, after which the 13th Infantry Regiment began moving from Bairoko to join the fighting around Munda.[14][15]

Prelude

After the initial American landings in New Georgia on 30 June, the Allies quickly secured Rendova as well as the other staging areas in southern New Georgia. On 2 July, elements from two US infantry regiments crossed the Blanche Channel to the western coast of New Georgia, landing around Zanana to begin the drive on Munda Point. To support this effort a separate landing group was detached to secure the area around Bairoko on the northern coast.[16] Allied planners believed that the area lay astride key Japanese lines of communication that were used to support the troops holding the Munda area. Consequently, the Northern Landing Group was tasked with blocking the Munda–Bairoko trail and securing Bairoko Harbor, which provided the sea link with the Japanese base at Vila on Kolombangara to the northwest.[17][18] To achieve this, a force of U.S. Marine Raiders, supported by two US Army infantry battalions, landed at Rice Anchorage, on the northern coast of New Georgia island, on 5 July.[19]

After the landing at Rice Anchorage US troops advanced inland and following a short battle captured Enogai on 10–11 July.[7] The Marine raiders consolidated their position around Enogai from 12 July and began patrolling the local area. Meanwhile, troops from the 3rd Battalion, 145th Infantry Regiment held a blocking position to the south along the Munda–Bairoko trail to prevent Japanese reinforcements being sent south to attack the US troops that had begun an advance on Munda airfield. The blocking position was initially successful when it was established on 8 July, but it came under increasing pressure due to its isolation. As Japanese attacks increased, the Americans were forced off the high ground. Casualties mounted and illness began to spread. A rifle company from the US 145th Infantry Regiment was dispatched to reinforce them on 13 July, but eventually Liversedge gave the order for the blocking position to be abandoned due to difficulties resupplying it,[20] and the soldiers returned to Triri on 17 July.[21] After the capture of Enogai, US patrols had been ordered to range south to establish contact with the troops from the 43rd Infantry Division around Munda, but this was not achieved.[22] During the period the block was in place, US casualties amounted to 11 men killed and 29 wounded, while around 250 Japanese were killed.[23]

On 18 July, Liversedge's force was reinforced by 700 Marines from Lieutenant Colonel Michael S. Currin's 4th Raider Battalion, which had previously been involved in actions around Segi Point, Viru Harbor and Wickham Anchorage in the south. These troops arrived aboard four high-speed transports, Ward, Kilty, McKean and Waters.[24] Due to their involvement in previous actions, Currin's force was significantly under strength. Nevertheless, their arrival at Rice Anchorage, which was being held by a detachment of the 3rd Battalion, 145th Infantry Regiment, brought Liversedge's men fresh supplies—up to 15 days' worth of rations, as well as ammunition and other stores—and allowed the US forces to begin planning the next stage of their advance in the area.[9][25]

Battle

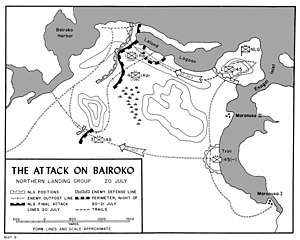

Liversedge subsequently made plans to capture Bairoko village, which lay on the eastern side of Bairoko Harbor, on 20 July.[26] The plan entailed a pincer movement: while the US Army detachment attacked the village from the southeast the Marines were to assault from the northeast.[27] This would see two companies from the 1st Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith) advance either side of the Leland Lagoon from Enogai, with Currin's 4th Raider Battalion following behind them to provide reinforcements if required. The 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel Delbert E. Schultz) would push inland from Triri along the Triri–Bairoko Trail to attack Bairoko from the south, converging with the 1st. Meanwhile, two companies of Marines would hold Enogai and elements from the 3rd Battalion, 145th Infantry Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel George G. Freer) would defend Triri and the supply depot around Rice Anchorage, along with a number of medical, supply and anti-tank detachments.[9][28][29]

The Japanese defensive positions around Bairoko were formidable and the garrison had been reinforced since the initial US landing at the Rice Anchorage.[27] Nevertheless, the attack began around 08:00 hours. The 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry Regiment began the approach, stepping off from Triri along the Triri–Bairoko Trail at this time. They were followed half an hour later by the 1st Raider Battalion, which had been reorganized into two full strength companies and two under strength companies, who set off from Enogai, to the north. The two full strength companies, Companies B and D, were committed to the assault, while A and C remained around Enogai, adopting a defensive posture. The 4th Raider Battalion followed shortly after the 1st, advancing along the Enogai–Bairoko Trial parallel with the southern shore of Leland Lagoon.[28] One platoon from the 1st Raider Battalion advanced along the sandspit to the north of the lagoon, on the extreme right of the advancing US forces.[30]

Throughout the morning, as the attack unfolded the 1st Raider Battalion advanced slowly over difficult terrain and skirmished with a series of Japanese outposts. By 10:45 hours, they came under heavy, sustained fire across their entire front, and the Marines deployed their reserve platoon to protect their left flank. Shaking out from their initial column-of-file formation, the Marines continued to advance their line, while Japanese snipers and light machine guns continued to harass the advance. By midday, the Japanese defenders withdrew to their main defensive line on several ridges around 300–500 yards (270–460 m) from Bairoko Harbor. Attempts to reduce this line were hampered by the lack of air support, which despite being requested, failed to arrive.[9][31]

The heaviest weapon the Marines possessed were their 60 mm mortars, which proved ineffective against the Japanese positions. Schultz's battalion, operating to the south possessed heavier 81 mm mortars, but ultimately poor radio communications and damaged telephone wire prevented coordination between the two battalions. Company D, 1st Raider Battalion was able to gain some ground, but eventually the advance came to a halt, as they came under heavy machine gun fire across their entire front from Japanese defenders occupying several bunkers constructed out of logs and coral. In an effort to outflank these positions, Liversedge, who had positioned himself with the northern most prong of the attack, ordered the 4th Raiders to attempt to turn the Japanese flank, advancing to the south of the 1st Raiders. With this assistance, two lines of the Japanese defensive position were captured, but eventually, under heavy fire from 90 mm mortars, the attack ground to a halt.[9][32]

Meanwhile, the southern advance by the 148th Infantry Regiment was held up by thick jungle and swamps, and was eventually halted about 1,000 yards (910 m) from Bairoko by Japanese holding the high ground. In the ensuing fight, heavy casualties were inflicted on the attacking US troops, who were unable to maneuver due to the terrain. By early afternoon, the 4th Raider Battalion had sustained over 90 critically injured personnel and their commander resorted to calling down mortar fire to break the deadlock.[9][32] The Marines to the north in the 1st Raider Battalion had suffered even more heavily, with around 200 casualties from the 1,000 men committed.[33]

Ultimately, the day-long assault by the Americans was unsuccessful.[34] Neither attacking force made any significant progress, and the air support that Liversedge had requested during the attack was not provided. Communications with Schultz's battalion were restored late in the day as the telephone wire was repaired by a party of the 145th Infantry Regiment, and as US casualties began to mount Liversedge considered his options. After discussing the situation with his battalion commanders, he decided to withdraw around 17:00 hours. Initially, Liversedge had considered bringing up reinforcements from the 145th to renew the attack, but these companies were too dispersed to concentrate quickly enough, and the Japanese were poised to bring in reinforcements during the night. After the order to withdraw was given, US medical personnel began collecting the wounded and moving them to an aid station to prepare them to be carried back to Enogai. The troops would withdraw in contact, covered by a firm base from two companies from the 4th Raiders, reinforced by a reserve company from the 145th Infantry Regiment.[9][35]

Aftermath

After calling-off the assault, the Americans withdrew to nearby Enogai in stages, moving firstly to a defensive perimeter on the night of 20/21 July. Largely the Japanese did not pursue them,[9] although they did launch a minor probing raid around 02:00 hours on 21 July, which resulted in five Japanese and one Marine being killed; another nine Marines were wounded. An hour later, a Japanese aircraft unsuccessfully attacked the American perimeter. Just before dawn on 21 July, air strikes were requested by US troops to cover their withdrawal, which began at 06:00 hours. Air support from land-based aircraft had been quite poor earlier in the campaign, but the support provided at this time amounted to the heaviest aerial bombardment of the campaign to that point.[36][37] The withdrawal lasted into the early afternoon. The final group of US troops reached Enogai just after 14:30 hours, withdrawing from the seaspit to the north of the Leland Lagoon. Casualties during the attack and the subsequent withdrawal amounted to 50 Americans killed while the Japanese lost at least 33 killed.[1] The wounded were evacuated in litters, assisted by local laborers, and were evacuated back to Enogai through multiple staging areas, and then by boat from the Leland Lagoon. From Enogai, the US wounded were flown back to Guadalcanal by three seaplanes; one of which was attacked by a Japanese fighter after take off, and returned to Enogai to remain overnight.[38]

As a result of their efforts to capture Bairoko, Liversedge's force was essentially spent.[39] Nevertheless, the American forces remained in the Enogai area until the end of the New Georgia campaign to gather information and interdict Japanese supply lines. Initially, US intelligence had assessed that the Japanese were using Bairoko to resupply and reinforce their troops who were guarding an airfield at Munda Point, southwest of Bairoko on the western coast of New Georgia and that by blocking the trail they prevented this from occurring. Analysis after the war, though, has shown this was not correct as the Japanese did not use the Bairoko–Munda trail for resupply efforts.[40][41]

In early August, Liversedge began another effort to capture Bairoko. At this time, reinforcements from the 25th Infantry Division arrived in New Georgia. These troops landed on the western coast, and began to advance on Bairoko from the south, after the U.S. and its allies successfully captured the airfield on 4/5 August. While troops from the 25th Division advanced north, carrying out mopping up operations, Liversedge's force advanced again across the Dragons Peninsula from Enogai towards Bairoko, commencing 23 August.[42] The Japanese subsequently evacuated New Georgia and abandoned Bairoko, which was captured by US forces on 24 August.[43][44]

Notes

- Shaw & Kane p. 143.

- Keogh, pp. 287–290

- Rentz, p. 19

- Miller, pp. 70–84

- Rentz, p. 52

- Rentz p. 111

- Miller pp. 99–103

- Stille p. 55

- Hoffman, Jon T. (1995). "Bairoko". From Makin to Bougainville: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Historical Center. Archived from the original (brochure) on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Miller pp. 127–129

- Rottman, p. 65

- Rentz p. 20

- Rentz p. 110 (map)

- Miller p. 105

- Shaw & Kane pp. 134–135

- Miller, p. 92

- Shaw & Kane, pp. 119

- Miller, pp. 70 & 94–95.

- Shaw & Kane, p. 121

- Hoffman, Jon T. (1995). "Enogai" (brochure). From Makin to Bougainville: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Historical Center. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Shaw & Kane pp. 131–133

- Miller p. 104

- Miller p. 104

- Rentz pp. 38 & 111

- Rentz p. 111

- Morison p. 202

- Shaw & Kane pp. 134–135

- Rentz p. 111

- Shaw & Kane pp. 123 & 134

- Rentz pp. 111–112

- Rentz, pp. 111–113

- Rentz pp. 112–115

- Rentz p. 116

- Miller pp. 129–131

- Rentz p. 116

- Horton pp. 105–108

- Rentz p. 117

- Rentz p. 118

- Stille p. 55

- Miller p. 104

- Shaw & Kane p. 133

- Miller p. 166 (map)

- Horton p. 109

- Miller pp. 167–171

References

- Horton, D. C. (1971). New Georgia: Pattern for Victory. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-34502-316-2.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). The South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Productions. OCLC 7185705.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 1122681293. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier,. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. VI. Castle Books. 0785813071.

- Rentz, John (1952). "Marines in the Central Solomons". Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 566041659. Retrieved May 30, 2006.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Duncan Anderson (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). "Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. OCLC 80151865. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47282-447-9.

Further reading

- Alexander, Joseph H. (2000). Edson's Raiders: The 1st Marine Raider Battalion in World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-020-7.

- Altobello, Brian (2000). Into the Shadows Furious. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-717-6.

- Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate. "Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Archived from the original on 26 November 2006. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Day, Ronnie (2016). New Georgia: The Second Battle for the Solomons. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253018779.

- Hammel, Eric M. (2008). New Georgia, Bougainville, and Cape Gloucester: The U.S. Marines in World War II A Pictorial Tribute. Pacifica Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3296-2.

- Hammel, Eric M. (1999). Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign, June-August 1943. Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-935553-38-X.

- Lofgren, Stephen J. Northern Solomons. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. p. 36. CMH Pub 72-10. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- Melson, Charles D. (1993). "Up the Slot: Marines in the Central Solomons". World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 36. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1993). "Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- McGee, William L. (2002). The Solomons Campaigns, 1942–1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville—Pacific War Turning Point, Volume 2 (Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII). BMC Publications. ISBN 0-9701678-7-3.

- Peatross, Oscar F. (1995). John P. McCarthy; John Clayborne (eds.). Bless 'em All: The Raider Marines of World War II. Review. ISBN 0-9652325-0-6.

- Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – Part I. Reports of General MacArthur. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994. Retrieved 2006-12-08.- Translation of the official record by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaux detailing the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy's participation in the Southwest Pacific area of the Pacific War.