Battle of Wickham Anchorage

The Battle of Wickham Anchorage took place during the New Georgia campaign in the Solomon Islands during the Pacific War from 30 June – 3 July 1943. During the operation US Marines and US Army troops landed by ship around Oleana Bay on Vangunu Island and advanced overland towards the anchorage where they attacked a garrison of Imperial Japanese Navy and Army troops. The purpose of the attack by the U.S. was to secure the lines of communication and supply between Allied forces involved in the New Georgia campaign and Allied bases in the southern Solomons. The U.S. forces were successful in driving the Japanese garrison from the area and securing the anchorage, which would later be used to stage landing craft for subsequent operations.

Background

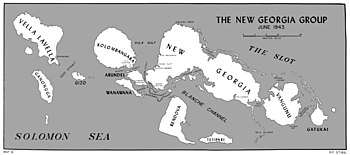

The battle was one of the first actions of the New Georgia campaign. Located on the southern tip of Vangunu, Wickham Anchorage lies at the southern end of the New Georgia Islands archipelago between Vangunu and Gatukai. In formulating their plans to secure the New Georgia islands, US planners assessed that several preliminary operations were required. This included the capture of Wickham Anchorage. The anchorage had little value for the Japanese, who secured the area with only a small garrison, but because of its proximity to New Georgia, it offered the Allies an important sheltered harbor that could support lines of supply as they advanced north from the Solomons through New Georgia and towards Bougainville. Consequently, they planned to use the area as a staging base for landing craft proceeding towards Rendova, where the main US force would be built up prior to landing around Munda Point to capture the Japanese airfield there. Other preliminary operations were envisaged to capture Viru Harbor and Segi Point to secure another staging base and a location for an airfield.[1][2]

Battle

At around 18:00 hours on 29 June, a small force of United States Marine Corps Raiders from the 4th Marine Raider Battalion and United States Army soldiers from the 2nd Battalion, 103rd Infantry Regiment embarked from the Russell Islands. A detachment of Colonel Daniel H. Hundley's Eastern Landing Force, these troops formed the Wickham Group, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Lester E. Brown.[3] The Marine element amounted to two companies (N and Q) who had not been deployed to Segi Point with the rest of their battalion as part of a preliminary operation a few days earlier. These companies were commanded by the battalion's executive officer Major James R. Clark, and were augmented by a demolitions platoon and headquarters element from the 4th Marine Raider Battalion, as well as a battery of 105 mm howitzers from the 152nd Field Artillery Battalion and a battery of 90 mm anti-aircraft guns from the 70th Coastal Artillery Battalion. A detachment of Seabees from the 20th Naval Construction Battalion were also assigned for base development work and engineer support tasks.[4][5]

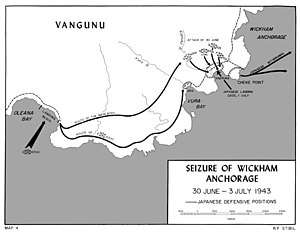

The invading force was carried aboard the destroyer transports Schley and McKean, upon which the Marines embarked, as well as seven Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs) for the US Army soldiers, escorted by a naval covering force under Rear Admiral George H. Fort aboard the destroyer Trever. The force was bound for a landing beach around 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to the west of the Vura village, around Oleana Bay.[6]

The area was defended by a platoon of Japanese troops from the 229th Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Genjiro Hirata,[7] and a company of the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force.[6] These forces formed part of Major General Minoru Sasaki's Southeast (Nanto) Detached Force.[8] US intelligence had estimated that the Wickham–Viru area was defended by between 290 and 460 Japanese personnel; in actuality there were a total of 310 troops (260 Army and 50 Navy) in the area.[9] Prior to the operation, the Allies had carried out a reconnaissance of the area and the District Officer Donald Gilbert Kennedy, a New Zealander, had worked to establish a track inland from Oleana Bay along which his scouts operated without the knowledge of the Japanese. In conceiving the landing, US planners had determined that a landing at Oleana Bay, followed by an advance overland via this track, would be the best approach to Wickham Anchorage. They estimated that the march would take about five to six hours.[10]

Bad weather hindered the voyage to Oleana Bay, but by 03:35 hours on 30 June the convoy reached their destination. Embarkation of the Marines into their LCVPs began shortly afterwards only to be stopped when US naval commanders realized they were too far west than had been planned. As a result, the Marines disembarked and the vessels moved further east. After this was completed, the Marines embarked once again, but found their run to the shore hampered by bad weather; rain and mist obscured the shore and the flares that had been fired by the scouts of the previously-landed reconnaissance party. In the confusion, the LCIs carrying the US Army troops veered off course and broke into the formation of LCVPs causing it to lose its cohesion. Disorganized, each boat made its own way to the shore where several were badly damaged by waves as they crashed against the coral reef; nevertheless, the landing was unopposed and the Marines suffered no casualties. A further wave of Marines landed around 06:30 hours, while the LCIs carrying the 103rd Infantry waited until daylight and landed around 07:20 hours at the intended landing beach.[11]

As the troops came ashore and the scattered groups rallied around a beachhead, they made contact with the reconnaissance party. Officers from this group had determined that the Japanese were concentrated around Kaeruka, and not at Vura as intelligence had previously assessed. As a result, Brown decided to change his plans: while the main body advanced overland towards Kaeruka via the inland track, another force moved along a coastal track in the direction of Vura. To support their advance, the battery of 105 mm howitzers fired from Oleana Bay. Naval gunfire support was also provided, as was air support from US Navy dive bombers.[11] As the Marines and soldiers advanced, the beachhead was held by the artillery batteries and Seabees.[12] The first major action between US and Japanese troops took place in the afternoon of 30 June in the Kaeruka area. During this action, Marine casualties amounted to 12 killed and 21 wounded.[11] US Army losses were 10 killed and 22 wounded, while Japanese casualties amounted to around 120.[13]

Meanwhile, also on 30 June, another action was fought around Vura by a company from the 103rd Infantry Regiment. As a result of this engagement, a detachment of 16 Japanese was forced to withdraw under heavy fire. After this US troops began consolidating their position around the beachhead for the night amidst heavy rain. Throughout the night, the perimeter came under mortar and machine gun fire from Japanese troops around Cheeke Point. Several Japanese barges attempted to land in the early morning, believing the area to be held by their own troops. Taken under heavy fire, 109 men out of the 120 on board the barges were killed; a further five were eventually killed ashore. The Marines lost two men killed during this fighting, while one US Army soldier was also killed. At daylight, the US commander, Brown, decided to move to Vura village. This was subsequently built up into a stronghold and from there, over the course of the next three days, the US troops harassed the Japanese, undertaking patrols supported by airstrikes and artillery. On 3 July, Brown led a force back to Kaeruka, fighting several minor actions that killed seven Japanese and destroyed several supply dumps.[14]

Aftermath

After Wickham Anchorage was secured on 3 July;[11] the Marines then moved by landing craft to Oleana Bay for rest before moving to Gatukai Island on 8 July in response to reports of a Japanese force there. The Marines spent two days searching for Japanese there before returning to Oleana Bay and from there to Guadalcanal; meanwhile, a US Army patrol eventually located the Japanese on Gatukai.[15]

The area was subsequently used as a staging base for US landing craft taking part in further operations in the New Georgia campaign,[11] supporting the movement of shipping from Guadalcanal or the Russel Islands. Ultimately, though, it was never developed into a major base.[16] Rendova was secured by US forces and by 2 July they began crossing from there to the western coast of New Georgia island, landing around Zanana. They began the advance westwards towards Munda Point several days later.[17] On 5 July, a force of Marines landed in the Kula Gulf region, on the northern coast of New Georgia island, around Rice Anchorage, to secure the Enogai and Bairoko areas and to block Japanese reinforcements heading south towards Munda.[18][19]

Notes

- Miller p. 69 (map) & p. 73

- Rentz p. 44

- Miller pp. 80–82

- Shaw & Kane p. 73

- Rentz p. 26

- Miller p. 82

- Stille p. 32

- Rentz p. 21

- Rentz p. 20

- Miller pp. 82–83

- Miller p. 83

- Shaw & Kane p. 76

- Rentz p. 48

- Rentz pp. 48–50

- Rentz p. 51

- Morison p. 153

- Miller pp. 92–94.

- Rentz p. 65

- Miller pp. 94–96

References

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1975) [1950]. Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. VI. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC 21532278.

- Rentz, John (1952). "Marines in the Central Solomons". Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved May 30, 2006.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Duncan Anderson (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942-43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472824509.

Further reading

- Altobello, Brian (2000). Into the Shadows Furious. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-717-6.

- Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate. "Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Archived from the original on 26 November 2006. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Day, Ronnie (2016). New Georgia: The Second Battle for the Solomons. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253018773.

- Dyer, George Carroll. "The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner". United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 12 September 2006. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Hammel, Eric M. (2008). New Georgia, Bougainville, and Cape Gloucester: The U.S. Marines in World War II A Pictorial Tribute. Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-7603-3296-7.

- Hammel, Eric M. (1999). Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign, June–August 1943. Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-935553-38-X.

- Hoffman, Jon T. (1995). "New Georgia" (brochure). From Makin to Bougainville: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Historical Center. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- Lofgren, Stephen J. Northern Solomons. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-10. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- Melson, Charles D. (1993). "Up the Slot: Marines in the Central Solomons". World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 36. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1993). "Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- McGee, William L. (2002). The Solomons Campaigns, 1942–1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville—Pacific War Turning Point, Volume 2 (Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII). BMC Publications. ISBN 0-9701678-7-3.

- Peatross, Oscar F. (1995). John P. McCarthy; John Clayborne (eds.). Bless 'em All: The Raider Marines of World War II. Review. ISBN 0-9652325-0-6.

- United States Army Center of Military History. "Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – Part I". Reports of General MacArthur. Retrieved 2006-12-08.- Translation of the official record by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaux detailing the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy's participation in the Southwest Pacific area of the Pacific War.