Battle of Himara

The Battle of Himara (Greek: Η Μάχη της Χειμάρρας) was a military conflict that took place in the Greco-Italian War in December 1940, during the counteroffensive of the Greek Army that followed the failed Italian invasion of Greece. After the Greek victory in Himara, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, admitted that one of the causes of the Italian defeat was the high morale of the Greek troops.

Background

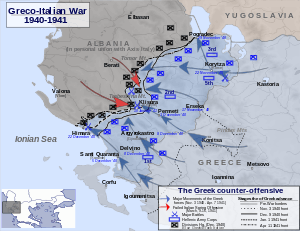

The Italian Army, initially deployed on the Greek–Albanian border, launched a major offensive against Greece on 28 October 1940. After a two-week conflict, Greece managed to repel the invading Italians in the battles of Pindus and Elaia–Kalamas. Beginning on 9 November, the Greek forces launched a counteroffensive and penetrated deep into Italian-held Albanian territory all over the front. As a result, the Greek forces entered the cities and towns of the region one after another: Korçë, on 22 November, Pogradec, on 30 November, Sarandë, on 6 December and Gjirokastër, on 8 December.[1]

Battle

On 13 December, Porto Palermo, a coastal village south of Himara came under the control of the Greek forces.[2] Two days later, the Greek 3rd Infantry Division continued the offensive toward Himara. However, the advance was slowed due to heavy enemy counter-action, supported by air force raids, as well as extremely harsh weather conditions. On 19 December, the Greek forces after a hard fight captured the Giami height.[3] Meanwhile, at the dawn of same day, the 3/40 Evzone Regiment (Colonel Thrasyvoulos Tsakalotos) launched, without artillery preparation, a surprise attack against the Italian troops at Mount Mali i Xhorët (or Mount Pilur), a strategic spot east of Himara. The Evzones of the regiment, after being informed about the topography of the region by locals, performed a charge with fixed bayonets from various positions against the Italian garrison.[4]

The snow was 3 metres (9.8 ft) high, which helped the advancing Greek troops to cross barbed wire and capture an Italian mountain battery.[2] After three days of fierce fighting, the men of the 3rd Division took control of the height, as well as the Kuç saddle. The capture of Kuç saddle gave access to the valley of Shushicë. Furthermore, the Italian troops lost six artillery guns, a mortar company and a multitude of war supplies. The Greek losses did not exceed 100 killed in action and wounded, while the Italians had approximately 400 casualties and more than 900 were taken prisoner.[3] On 21 December, the Greek forces captured the height of Tsipista north-west of Himara. To avoid encirclement, the Italians abandoned Himara. Finally, the Greek troops entered the town in the morning on 22 December, where they were welcomed by the locals with enthusiastic celebrations.[3]

Aftermath

The capture of Himara was celebrated as a major success in Greece and proved that the Greek army was in condition to continue the advance pushing the Italians further north.[5][6] On the other hand, the Italian headquarters was alarmed by the Greek success, and on 24 December Benito Mussolini addressed his concerns to the Italian military commander, Ugo Cavallero.[3] In his letter, Mussolini does not doubt that one of the causes of the Italian defeat was the high morale of the Greek forces, which led to their capture of Himara.[7]

Footnotes

- Willmott 2008.

- Storrs & Graves 1940, p. 112.

- Gedeon 1997, p. 117.

- Terzakis 1990, pp. 149–150.

- Cervi 1972, p. 188.

- Willingham 2005, p. 36.

- Tsirpanlis 1992, pp. 111–190.

References

- Cervi, Mario (1972). The Hollow Legions: Mussolini's Blunder in Greece, 1940–1941. transl. from the Italian by Eric Mosbacher. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-1351-3.

- Gedeon, Dimitrios (1997). An Abridged History of the Greek-Italian and Greek-German War, 1940–1941: (land operations). Athens: Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate. ISBN 978-960-7897-01-5.

- Storrs, Sir Ronald; Graves, Philip Perceval (1940). A Record of the War. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 1523010.

- Terzakis, Angelos (1990). Ελληνική Εποποιϊα 1940–1941 [The Greek Epic 1940–1941] (in Greek). Athens: Hellenic Army General Staff. OCLC 26524374.

- Tsirpanlis, Zacharias N. (1992). "The Morale of the Greek and the Italian Soldier in the 1940–41 War". Balkan Studies. New York: Institute for Balkan Studies. 33. ISSN 0005-4313.

- Willingham, Matthew (2005). Perilous Commitments: The Battle for Greece and Crete: 1940–1941. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-236-1.

- Willmott, H. P. (2008). The Great Crusade: A New Complete History of the Second World War (revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-191-1.