Colonial Assam

Colonial Assam (1826–1947) refers to the period of History of Assam between the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo and Independence of India when Assam was under the British colonial rule. The political institutions and social relations that were established or severed during this period continue to have a direct effect on contemporary events. The legislature and political alignments that evolved by the end of the British rule continued in the post Independence period. The immigration of farmers from East Bengal and tea plantation workers from Central India continue to affect contemporary politics, most notably that which led to the Assam Movement and its aftermath.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Assam |

|---|

|

|

Proto-historic |

|

Late Medieval |

|

Modern |

|

Contemporary |

| Categories |

|

British annexation of Assam

The region that came to be known as undivided Goalpara district came under British rule after the transfer of the Deewani from the Mughal Emperor on August 12, 1765. Due to indigenous ethnic influences on the region the police thanas of Dhubri, Nageswari, Goalpara and Karaibari were placed under a special administrative unit called "North-Eastern Parts of Rangpur" (note: this Rangpur is in present-day Bangladesh) in January 1822.[1] The First Anglo-Burmese War commenced in 1824, and by March 28 the British had occupied Guwahati, when the Raja of Darrang (a tributary of the Ahom kingdom) and some petty chieftains submitted themselves to the British, who made rudimentary administrative arrangements by October 1824.[2] The Burmese occupiers retreated from the Ahom capital of Rangpur in January 1825 and the nearly the whole of Brahmaputra Valley fell into British hands.[3] In the war against the Burmese the Ahoms did not help the British. In 1828, the Kachari kingdom was annexed under the Doctrine of Lapse after the king Govinda Chandra was killed. In 1832, the Khasi king surrendered and the British increased their influence over the Jaintia ruler. In 1833, upper Assam became a British protectorate under the erstwhile ruler of the Ahom kingdom, Purandhar Singha, but in 1838 the region was formally annexed into the British empire. With the annexation of the Maran/Matak territory in the east in 1839, the annexation of Assam was complete.

Bengal Presidency (1826–1873)

Assam was included as a part of the Bengal Presidency. The annexation of upper Assam is attributed to the successful manufacture of tea in 1837, and the beginning of the Assam Company in 1839.

Planter Raj

Under the Wasteland Rules of 1838, it became nearly impossible for natives to start plantations. After the liberalization of the rules in 1854, there was a land rush. The Chinese staff that was imported earlier for the cultivation of tea left Assam in 1843, when tea plantations came to be tended by local labour solely, mainly by those belonging to the Bodo-Kachari ethnic groups.[4] From 1859 central Indian labour was imported for the tea plantations. This labour, based on an unbreakable contract, led to a virtual slavery of this labour group. The conditions in which they were transported to Assam were so horrific that about 10% never survived the journey. The colonial government imposed a ban on opium cultivation and obtained a monopoly over the opium trade.[5]

Protests and Revolts

There were immediate protests and revolts against the British occupation. In 1828, two years after the Treaty of Yandabo, Gomdhar Konwar rose in revolt against the British, but he was easily suppressed. In 1830 Dhananjoy Burhagohain, Piyali Phukan and Jiuram Medhi rose in revolt, and they were sentenced to death. In the Indian rebellion of 1857, the people of Assam offered resistance in the form of non-cooperation, and Maniram Dewan and Piyali Baruah were executed for their roles. In 1861 peasants of Nagaon gathered at Phulaguri for a raiz mel (peoples' assembly) to protest against taxes on betel-nut and paan.[6] Lt. Singer, a British officer got into a fracas with the peasants and was killed, after which the protests were violently suppressed.[7]

Chief Commissioner's Province (1874–1905)

In February 1874 Assam proper, Cachar, Goalpara and the Hill districts were instituted as a separate province,[8] primarily on a long-standing demand from the tea planters.[9] Also known as North-East Frontier, its status was upgraded to a Chief Commissioner's Province, a non-regulation province, with the capital at Shillong. Assamese, which had been replaced in 1837 by Bengali, was reinstated alongside Bengali as the official language.

In September of the same year, Sylhet was separated from the Bengal Presidency and added to the new province.[10] The people of Sylhet submitted a memorandum to the Viceroy protesting the inclusion in Assam.[11] The protests subsided when the Viceroy, Lord Northbrook, visited Sylhet to reassure the people that education and justice would be administered from Bengal,[12] and when the people in Sylhet saw the opportunity of employment in tea estates in Assam and a market for their produce.[13]

The new administration effected a policy of migrations: tea laborers into tea estates and agriculturalists from East Bengal into Assam ignoring history and culture of peoples.[14]

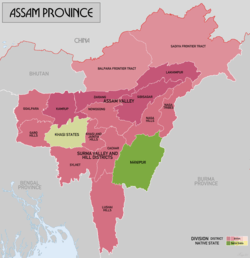

The new Province included the five districts of Assam proper (Kamrup, Nagaon, Darrang, Sibsagar and Lakhimpur), Goalpara, Cachar, the Hill districts (Lalung (Tiwa) Hills, Khasi-Jaintia Hills, Garo Hills, Naga Hills), and Sylhet comprising about 54,100 sq miles.[15]

In 1889, oil was discovered at Digboi giving rise to an oil industry. In this period Nagaon witnessed starvation deaths, and there was a decrease in the indigenous population, which was more than adequately compensated by the immigrant labor. Colonialism was well entrenched, and the tea, oil and coal-mining industries were putting increasing pressure on the agricultural sector which was lagging behind.

The peasants, burdened under the opium monopoly and the usury by money lenders, rose again in revolt. Numerous raiz mels decided against paying the taxes. The protests culminated in a bayonet charge against the protesters at Patharughat in 1894. At least 15 were left dead and in the violent repression that followed villagers were tortured and their properties were destroyed or looted. In 1903, Assam Association was formed with Manik Chandra Baruah as the first secretary.

Eastern Bengal and Assam under Lt. Governor (1906–1912)

Bengal was partitioned and East Bengal was added to the Chief Commissioner's Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam. The new region, now ruled by a Lt. Governor, had its capital at Dhaka. This province had a 15-member legislative council in which Assam had two seats. The members for these seats were recommended (not elected) by rotating groups of public bodies.

The Partition of Bengal was strongly protested in Bengal, and the people of Assam were not happy either. Opposition to partition was co-ordinated by Indian National Congress, whose President was then Sir Henry John Stedman Cotton who had been Chief Commissioner of Assam until he retired in 1902. The partition was finally annulled by an imperial decree in 1911, announced by the King-Emperor at the Delhi Durbar. The Swadeshi movement (1905-1908) from this period, went largely unfelt in Assam, though it stirred some, most notably Ambikagiri Raychoudhury.

Beginning 1905 peasants from East Bengal began settling down in the riverine tracts (char) of the Brahmaputra valley encouraged by the colonial government to increase agricultural production. Between 1905 and 1921, the immigrant population from East Bengal increased four folds. The immigration continued in post colonial times, giving rise to the Assam Agitation of 1979.

Assam Legislative Council (1912–1920)

The administrative unit was reverted to a Chief Commissioner's Province (Assam plus Sylhet),[16] with a Legislative Council added and Assam Province was created. The Council had 25 members, of which the Chief Commissioner and 13 nominated members formed the bulk. The other 12 members were elected by local public bodies like municipalities, local boards, landholders, tea planters and Muslims.

As Assam became involved in the Non-cooperation movement, the Assam Association slowly transformed itself into the Assam Pradesh Congress Committee (with 5 seats in AICC) in 1920–21.[17]

Dyarchy (1921–1937)

Under the Government of India Act 1919 the Assam Legislative Council membership was increased to 53, of which 33 were elected by special constituencies. The powers of the Council were increased too; but in effect, the official group, consisting of the Europeans, the nominated members etc. had the most influence. Syed Muhammed Saadulah served as Minister of Education and Agriculture from 1924 to 1929. He was later made a Member of the Executive Council of the Governor of Assam holding the portfolios for Law and Order and Public Works from 1929 to 1930 and for Finance and Law and Order from 1930 to 1934.

Assam Legislative Assembly (1937–1947)

Under the Government of India Act 1935, the Council was expanded into an Assembly of 108 members, with even more powers. The period saw the sudden rise of Gopinath Bordoloi and Muhammed Saadulah and their tussle for power and influence.

Notes

- (Bannerjee 1992, pp. 4–5)

- (Bannerjee 1992, pp. 5–6)

- (Bannerjee 1992, p. 7)

- " During the 1840s and 1850s, alongside the Chinese and the Nagas, the Assam Company tried its best to recruit from amongst other local groups in Upper Assam." (Sharma 2009:1293) " Assamese elites played a key role in helping the tea industry identify Kacharis as potential labour." (Sharma 2009:1300)

- "During the 1840s and 1850s, the East India Company arranged to sell Bengal opium in Assam through government agents. This met with little success due to the abundance of the local supply. At this juncture, a British judge's suggestion was, 'Opium they should have, but to get it they should be made to work for it.' In 1861, a ban on local opium cultivation was instituted in Assam. Opium sales were henceforth to be a state monopoly." (Sharma 2009:1297)

- "In September 1861, nearly four thousand peasants in and around Phulaguri came down to the office of the district magistrate at Nowgong and waited upon a deputation to him with the object of presenting a memorandum to protest against government proposal to introduce License Act, Income Tax on bettle nut and etc." (Chattipadhyay 1991:817)

- "(T)he Lieutenant on duty, along with a large contingent of police force, ordered the peasants to disperse. Peasants defied the order which resulted in an encounter causing the death of a few peasants and also of the European lieutenant." (Chattopadhyay 1991:817)

- (Hossain 2013:260)

- "The tea planters had long demanded the creation of an exclusive province to secure their own interests and the efficient use of state tools." (Hossain 2013:260)

- "To make (the Province) financially viable, and to accede to demands from professional groups, (the colonial administration) decided in September 1874 to annex the Bengali-speaking and populous district of Sylhet."(Hossain 2018:260)

- " A memorandum of protest against the transfer of Sylhet was submitted to the viceroy on 10 August 1874 by leaders of both the Hindu and Muslim communities." (Hossain 2013:261)

- "It was also decided that education and justice would be administered from Calcutta University and the Calcutta High Court respectively." (Hossain 2013:262)

- "They could also see that the benefits conferred by the tea industry on the province would also prove profitable for them. For example, those who were literate were able to obtain numerous clerical and medical appointments in tea estates, and the demand for rice to feed the tea labourers noticeably augmented its price in Sylhet and Assam enabling the Zaminders (mostly Hindu) to dispose of their produce at a better price than would have been possible had they been obliged to export it to Bengal." (Hossain 2013:262)

- "The administration of this new province adopted two major policies: first, it would ensure the smooth recruitment of tea labourers from outside and, secondly, it would oversee a policy of sponsored migration of Bengali peasants from East Bengal districts to the countryside of Sylhet and Assam to facilitate the expansion of agriculture. This was done under the slogan 'Grow more food'. Evidently, colonial officialdom did not consider historical or cultural contiguity when it declared Assam to be a new administrative province." (Hossain 2013:262)

- The Assam Legislative Assembly

- (Imperial Gazetteer of India 1931, p. 32)

- "After the formation of a few district Congress Committees, the Assam provincial Congress Committee was constituted in June, 1921. By then the Assam Association had fully assimilated itself with the Congress." (Saikia 1985:397)

References

- Bannerje, A C (1992). "Chapter 1: The New Regime, 1826-31". In Barpujari, H K (ed.). The Comprehensive History of Assam: Modern Period. IV. Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam. pp. 1–43.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baruah, S. L. (1993), Last Days of Ahom Monarchy, New DelhiCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gait, Edward A (1906), A History of Assam, CalcuttaCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chattopadhyay, Ramkrishna (1991). "Colonisation of Assam and Phulaguri Peasant Uprising (1861): Summary". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 52: 817–818. JSTOR 44142714.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guha, Amalendu (1977), Planter-Raj to Swaraj, DelhiCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 250–287. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saikia, Rajendranath (1985). "Assam Association as the Forerunner of Congress Movement". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 46: 393–399. JSTOR 44141379.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, Jayeeta (2009). "'Lazy' Natives, Coolie Labour, and the Assam Tea Industry". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 43 (6): 1287–1324. JSTOR 40285014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, Jayeeta (2011), Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India, Durham and London: Duke University PressCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Assam with Bhutan (Map). Imperial Gazetteer of India. 1931. p. 32. Retrieved February 5, 2013.