Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta (Arabic: بنزرت ![]()

Bizerte بنزرت | |

|---|---|

Bizerte City Hall in Belgique Street area | |

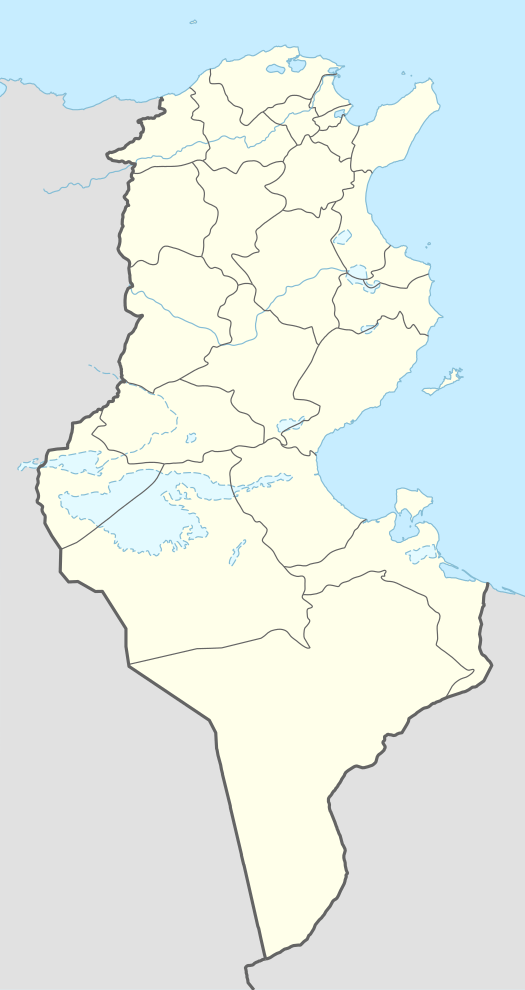

Bizerte Location in Tunisia | |

| Coordinates: 37°16′40″N 9°51′50″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Bizerte Governorate |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 34[1] km2 (13.127 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5[2] m (16 ft) |

| Population (2014[1]) | |

| • City | 142,966[1] |

| • Density | 3,363/km2 (8,712/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 401,144 |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| Postal code | 7000 |

| Area code(s) | +216 (Tun) 72 (Bizerte) |

| Website | www.commune-bizerte.gov.tn |

Names

Hippo is the latinization of a Punic[3][4] name (Punic: 𐤏𐤐𐤅𐤍, ʿpwn),[5] probably related to the word ûbôn, meaning "harbor".[6] To distinguish it from Hippo Regius (the modern Annaba, in Algeria), the Greeks and Romans used several epithets. Scylax of Caryanda mentions it as Hippo Acra and Hippo Polis ("Hippo the City").[7][3] Polybius mentions it as Hippo Diarrhytus (Greek: Ἱππὼν διάρρυτος, Hippōn Diárrhytos), "Hippo Divided-by-the-Water", in reference to the town's prominent canal.[4] It also appears in Roman, Vandal, and Byzantine sources as Hippo Zarytus.[8] Its Arabic name Banzart (بنزرت) and the French and English forms derived from it all represent phonetic developments of its ancient name.[3]

History

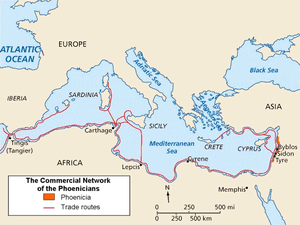

Phoenicians from Sidon founded Bizerte, one of the oldest cities in Tunisia, around 1100 BC.[9][10]

Antiquity : (1100 BC to 647 AD)

- Initially a small Phoenician harbor for maritime trading in the western Mediterranean, the settlement lay 30 km (18.5 mil) north of Utica and 50 km (31 mil) northwest of Carthage, other cities founded by Phoenicians.

Around 950 BC the city came under the influence of Carthage during the reign of Queen Dido/Elissa, In 309 BC, during the Greek–Punic Wars and after the defeat of Agathocles, the city and Sicily returned to the Carthaginian Republic. Several Carthaginian generals used its port during the Punic Wars of 264-146 BC - such as Hamilcar Barca, Mago, Hasdrubal and Hannibal.

- In 149 BC the first Roman raids occurred. During the ascendancy of Julius Caesar the Romans occupied the city, calling it Hippo Diarrhytus. The city regained its prosperity and progress from the reign of Augustus (Emperor from 27 BC to 14 AD) and maintained maritime relations with Ostia and Rome, as shown by a mosaic decorating its commercial representation in the square of Forum of Corporations. Christianity spread in the city under the Empire.

- In 439 AD Genseric, the king of the Vandals (East Germanic tribes) and his followers invaded the city and used the port as a base for invasions into other parts of the Western Roman Empire: the city of Rome and the islands of Sardinia, Malta, Corsica and Sicily. The town appears on the medieval Peutinger Map.

- From 534 AD to 642 AD the city came under the control of the Byzantine Empire after a defeat of the Vandals in 534; they build the Fort of Bizerte (now the Fort of Kasba).

Later history

Arab armies took Bizerte in 647 in their first invasion of the area, but the city reverted to control from Constantinople until the Byzantines were defeated and finally driven from North Africa in 695–98. The troops of Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire captured the city in 1535; the Turks took it in 1574. The city then became a corsair harbour and struggled against the French and the Venetians.

With its occupation of Tunisia in 1881, France gained control of Bizerte and built a large naval harbour in the city.

In 1924, after the French government officially recognized the Soviet Union (USSR), the western military fleet of White Russia that had been kept in the port of Bizerte was returned to the Soviet government. The ships were never moved from the port and finally were sold there as scrap metal.

In March 1939, towards the end of the Spanish Civil War, Spanish Republican Navy Commander Miguel Buiza ordered the evacuation of the bulk of the Republican fleet. Three cruisers, eight destroyers and two submarines left Cartagena harbor and reached Bizerte, where the French authorities impounded them.[11]

During the Second World War, the German and Italian armies occupied Bizerte until Allied troops defeated them on 7 May 1943. During the fighting between the Allied forces and the German Army, many of the city's inhabitants fled to the countryside or to Tunis. The city suffered significant damage during the battle.[12]

Due to Bizerte's strategic location on the Mediterranean, France retained control of the city and her naval base after Tunisian independence in 1956. In 1961 Tunisian forces blockaded the area of Bizerte and demanded French withdrawal. The face-off escalated when a French helicopter took off and drew fire. The French brought in reinforcements; when these were fired upon, France took decisive military action against the Tunisian forces. Using superior weapons and decisive force the French took Bizerte and Menzel Bourguiba. During three days in July 1961, 700 Tunisians died (1200 wounded); the French lost 24 dead (100 wounded).[13]

Meetings at the UN Security Council and other international pressure moved France to agreement; the French military finally abandoned Bizerte on 15 October 1963.[14]

Geography

Location

Bizerte is on a section of widened inlet and east-facing coast of the north coast of Tunisia, 15 kilometres from Ras ben Sakka (the northernmost point in Africa on the Mediterranean Sea), 20 kilometers northeast of the Ichkeul lake (a World Heritage Site), 30 kilometers (18 miles) north of the archaeological site of Utica and 65 kilometers north of Tunis.

it has to the west coastal hills forming an outcrop of the Tell Atlas with well-conserved woods and vantage points. Its associated beaches include Sidi Salem, La Grotte, Rasenjela, and Al Rimel. It is on a section of Mediterranean climate coastline, close to Sardinia and Sicily, as opposed to coasts in the south of the country which have a year-round dry desert climate.

The city is centered on the north shore of the canal of Bizerte linking the Mediterranean Sea to a tidal lake, the Lac de Bizerte which is larger than all parts of the town combined, to the immediate south. Built-up areas are in three directions:

- South-west along the widening canal with jetties at Pecherie and Jarrouba, the latter associated with Bizerte-Sidi Ahmed Air Base adjoining the opening of the lake and military/rescue heliport.

- North are Sidi Salam and Corniche. They are within meters of the coast and on coast-facing slopes of the Ain Berda, a range of hills toward Cap Blanc, a small headland in the Ain Damou Plage natural conservation area.

- Zarzouna, Menzel Jemil and Menzel Abderrahmane are on the south shore of the canal, formed by the locality of Zarzouna and the towns of Menzel Jemil and Menzel Abderrahmane, by a moveable bridge and both Menzels face the lake itself. The rest of the isthmus on which they stand is the gently rising Foret de Remel, reaching a high point east of its forest area at Cap Zebib.

Transport

The bridge leads to the motorway A4 leading to Tunis–Carthage International Airport and the capital. On the town side the P11 passes semi-rural Louata, hugs Ichkeul Lake and branches into a western route, the P7, leading directly to Tabarka on the coast next to the Algerian border. The P11 leads south-west to Béja, a governorate center, in the foothills of the Tell Atlas, forks into several roads at Bou Salem, a small town in a broad fertile plain, and climbs to Firnanah passing two high-altitude lakes and also approaching the north-west border with Algeria.

Climate

Bizerte enjoys a hot-summer mediterranean climate, with mild, rainy winters and hot, dry summers. The Mediterranean Sea breeze makes summers cooler but more humid.[15]

| Climate data for Bizerte (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2017) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

34.2 (93.6) |

40.4 (104.7) |

46.0 (114.8) |

46.6 (115.9) |

48.0 (118.4) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.5 (104.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

48.0 (118.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

29.1 (84.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.2 (24.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 88.8 (3.50) |

73.9 (2.91) |

57.6 (2.27) |

50.6 (1.99) |

23.2 (0.91) |

10.6 (0.42) |

2.2 (0.09) |

6.8 (0.27) |

44.3 (1.74) |

61.3 (2.41) |

93.4 (3.68) |

115.2 (4.54) |

627.9 (24.73) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.3 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 6.5 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 11.4 | 77.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 75 | 70 | 68 | 69 | 75 | 78 | 83 | 83 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 142.6 | 163.9 | 217.0 | 237.0 | 303.8 | 330.0 | 384.4 | 356.5 | 267.0 | 207.7 | 153.0 | 133.3 | 2,896.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 4.6 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 9.8 | 11.0 | 12.4 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 7.9 |

| Source 1: Institut National de la Météorologie (precipitation days 1961–1990 and extremes 1950–2017)[16][17][18][note 1] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes 1901–1992)[20] Arab Meteorology Book (humidity and sun)[21] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.6 °C (58.3 °F) | 14.0 °C (57.2 °F) | 14.3 °C (57.7 °F) | 15.1 °C (59.2 °F) | 17.2 °C (63.0 °F) | 19.9 °C (67.8 °F) | 23.4 °C (74.1 °F) | 24.9 °C (76.8 °F) | 23.8 °C (74.8 °F) | 21.7 °C (71.1 °F) | 18.8 °C (65.8 °F) | 16.2 °C (61.2 °F) |

Economy

Bizerte's economy is very diverse. There are several military bases and year-round tourism. As a tourist centre the region is however not as popular as the eastern coast of Tunisia. There is manufacturing (textile, auto parts, cookware), fishing, fruits and vegetables, and wheat.

Miscellaneous

- The port of Bizerte is being developed into a significant Mediterranean yachting marina that was scheduled to open in May 2012. The superyacht section of the marina will be called Goga Superyacht Marina, and will have berths for yachts of up to 110m in length. It is expected that this will give a significant boost to the local economy as the yacht owners and also the hundreds of professional crew will become year-round consumers. The service industries supplying the yachts will gradually develop and bring additional employment.[22]

- The actor Abdelmajid Lakhal was born in Bizerte.

- The Teapacks song "Lo haya lano klum" is about how bandleader Kobi Oz' family were expelled from Bizerte by the Nazis in 1942.

Titular see

Hippo Diarrhytus is a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1989–2002 it was held by Mgr. Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz, then by Mgr. Jose Paala Salazar, O.P. in 2002–2004 and by Mrg. Manfred Grothe since October 14, 2004. The city and see of Hippo Diarrhytus should not be confused with those of Hippo Regius where Saint Augustine of Hippo was the bishop.

Serbian Army in Bizerte 1915-1919

Army

After the Serbian army's retreat through Albania in 1915, during the World War I, part of the army was transported by the French navy to their naval base in Bizerte. Serbian soldiers, and a small number of civilians, arrived in Bizerte on three occasions. In December 1915 and early 1916, after the Albanian Golgotha, then later in 1916 after the first clashes on the Salonica Front in Greece and in the early 1917 when Serbian volunteers began to gather in Bizerte. During the entire war, the soldiers were transported to the Salonica Front while the wounded were transported back to Tunisia. It is estimated that over 60,000 Serbian soldiers passed through the camp. The training of the volunteers was organized in the camp, education of the disabled but also the cultural events.[23] French-Serbian dictionary was compiled and published by Veselin Čajkanović in Bizerte. Out of 7,000 copies, 5,000 and 1,000 were distributed to Serbian and French soldiers, respectively, while the remaining 1,000 copies were sold, with money being donated to the war invalids.[24]

Serbian wounded soldiers were originally placed in the Lambert barrack. Few days later they were relocated to the 5 km (3.1 mi) away camp Lazouaz. Almost 200 barracks were built in the camp complex.[24] Citizens of Bizerte, French soldiers and administration were highly obliging to the Serbs, especially the Bizerte governor, admiral Émile Guépratte. He was involved in the care of the soldiers on daily basis and organized ceremonial greetings for every ship upon arrival. The last Serbian soldiers left Bizerte on 18 August 1919.[23] Admiral Guépratte directly disobeyed the order from the French High Command by which he was ordered to dislocate Serbs into the Sahara's hinterland.[25] When Guépratte visited Belgrade for the first time in 1930, he was awaited by the crowd which carried the admiral on their shoulders from the Belgrade Main railway station to the Slavija Square. The street where the admiral was carried, today bears his name (Serbian: Улица адмирала Гепрата, romanized: Admiral Guépratte Street).[26]

Hospitals

In the Northern Africa, Serbian wounded soldiers were treated in the hospitals in Bizerte, Tunis, Sousse, Sidi Abdala, Algiers, Oran and Annaba. From December 1915 to August 1919, a total of 41,153 Serbian soldiers were treated. In Tunisian hospitals, 833 soldiers died (typhus, malaria, wounds, hunger and frostbites). In Sidi Abdala, local population helped the Serbs providing food, medicines and nurture. A total of 1,722 people died there.[25]

Cemeteries

The dead in Bizerte, Sous and Tunis were buried in the memorial ossuary on the Christian cemetery in Bizerte. Those who died in Sidi Abdala were interred on the joint French-Serbian military cemetery. Those two cemeteries are the largest of all in Northern Africa where Serbian soldiers were buried - a total of 24 cemeteries in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, with 3,005 buried soldiers.[25][27]

Notable residents

- Georges Madon (1892-1924), ace pilot

- Claude Pujade-Renaud (b. 1932), writer

- Maurice Poli (b. 1933), actor

- Abdelmajid Lakhal (1939-2014), actor and theatre director

- Nikita Mandryka (b. 1940), cartoonist

- Lionel Duroy (b. 1949), writer

- Pierre Cohen (b. 1950), politician

- Jean-Marc Luisada (b. 1958), pianist

- Nabil Karoui (b. 1963), politician and businessman

- Mondher Kebaier (b. 1970), football coach

- Hassen Bejaoui, (b. 1975), former footballer

- Malek Jaziri (b. 1984), tennis player

- Hamdi Harbaoui (b. 1985), footballer

- Souheïl Ben Radhia (b. 1985), footballer

- Farouk Ben Mustapha (b. 1989), footballer

- Hamza Mathlouthi (b. 1992), footballer

- Bilel Saidani (b. 1993), footballer

International relations

Sister cities

Bizerte is twinned with:

Cooperation agreement

Notes

- The Station ID for Bizerte is 11414111.[19]

References

- (in French) Mnicipalité de Bizerte Archived January 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- City Coordinates (Dateandtime.info)

- Dr Mahmoud ABIDI(french) (2008-02-05). "bizerteyahasra". bizerteyahasra.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- Perseus Digital Library.

- Ghaki (2015), p. 66.

- Brown (2013), p. 326.

- Tunisia, Stelfair. "Chambre de Commerce et d'Industrie du Nord-Est Bizerte". www.ccibizerte.org. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- Hippo Zarytus(in Perseus Digital Library).

- "Bizerte, Ya Hasra, le blog de Mahmoud ABIDI". 2013-08-09. Archived from the original on 2013-08-09. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- ABIDI, M. "Bizerte, Ya Hasra, le blog de Mahmoud ABIDI". Bizerte, Ya Hasra, le blog de Mahmoud ABIDI (in French). Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- Thomas, Hugh (2001). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin Books. p. 877.

- "To Bizerte With The Ii Corps". History.army.mil. Archived from the original on 2012-07-26. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United (2018-10-31). Regional Conference on building a future for sustainable small-scale fisheries in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 978-92-5-130553-9.

- Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United (2018-10-31). Regional Conference on building a future for sustainable small-scale fisheries in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 978-92-5-130553-9.

- "Climate Bizerte – Table". Climate–Data.Eu. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- "Les normales climatiques en Tunisie entre 1981 2010" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Données normales climatiques 1961-1990" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Les extrêmes climatiques en Tunisie" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Réseau des stations météorologiques synoptiques de la Tunisie" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Klimatafel von Bizerte / Tunesien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Appendix I: Meteorological Data" (PDF). Springer. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Morley Yachts (2009-07-29). "Goga Superyacht Marina". Gogamarina.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- "Srpska vojska u Bizerti" (in Serbian). Istorijska biblioteka.

- Branko Pejović (8 February 2000). Срби на северу Африке учили француски [Serbs in North Africa learned French language]. Politika (in Serbian).

- Slobodan Kljakić (16 March 2015), "Svedočanstvo o srpskim vojnicima u severnoj Africi", Politika (in Serbian)

- Beograd - plan grada. M@gic M@p. 2006. ISBN 86-83501-53-1.

- Ranko Pivljanin (24 May 2010). "Večna straža kraj Bizerte" (in Serbian). Blic.

Bibliography

- Brown, Peter (2013), Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1400844531.

- Ghaki, Mansour (2015), "Toponymie et Onomastique Libyques: L'Apport de l'Écriture Punique/Néopunique" (PDF), La Lingua nella Vita e la Vita della Lingua: Itinerari e Percorsi degli Studi Berberi, Studi Africanistici: Quaderni di Studi Berberi e Libico-Berberi, No. 4, Naples: Unior, pp. 65–71, ISBN 978-88-6719-125-3, ISSN 2283-5636. (in French)

External links

- "Encyclopedia of the Orient"

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Pétridès, Sophron (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.