Invasion of Corsica (1553)

The Invasion of Corsica of 1553 occurred when French, Ottoman, and Corsican exile forces combined to capture the island of Corsica from the Genoese.[1]

| Invasion of Corsica | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman-Habsburg wars | |||||||

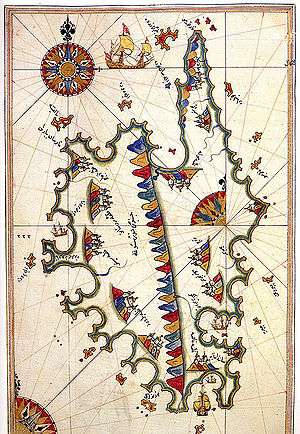

Historic map of Corsica by Piri Reis | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| |||||||

The island had considerable strategic importance in the western Mediterranean, being at the heart of the Habsburg communication network and serving as a forced stopover for small boats sailing between Spain and Italy.[2]

The island had been administered since 1453 by the Genoese Bank of Saint George. The invasion of Corsica was accomplished for the benefit of France.[3]

The island had major strategic importance, as it was located on the sea route between Spain and Italy, which was vital for the Holy Roman Empire.[2]

Context

The French king Henry II had entered into a major war with the Habsburg Emperor Charles V in 1551, starting the Italian War of 1551–1559. Looking for allies, Henry II, following the Franco-Ottoman alliance policy of his father Francis I, sealed a treaty with Suleiman the Magnificent in order to cooperate against the Habsburgs in the Mediterranean.[4]

The Ottomans, accompanied by the French ambassador Gabriel de Luetz, had already defeated a Genoese fleet under Andrea Doria in the Battle of Ponza the previous year in 1552. On 1 February 1553, a new Franco-Ottoman treaty of alliance, involving naval collaboration against the Habsburgs, had been signed between France and the Ottoman Empire.[5]

Operations

Summer campaign (1553)

The Ottoman admirals Turgut and Koja Sinan, together with a French squadron under Baron Paulin de la Garde, raided the coasts of Naples, Sicily, Elba, and then Corsica.[5][6]

The island of Corsica was occupied by the Genoese at the time.[2]

The Ottoman fleet supported the French by ferrying the French troops of Parma under Marshal Paul de Thermes from Siennese Maremma to Corsica.[7] The French were also supported by Corsican exiles under Sampiero Corso and Giordano Orsini (Gallicized as "Jourdan des Ursins") in this adventure. The invasion had not been explicitly approved beforehand by the French king however.[2] Bastia was captured on 24 August 1553, and Paulin de la Garde arrived in front of Saint-Florent on 26 August.[2] Bonifacio was captured in September.[2] With only Calvi remaining to be captured, the Ottomans, loaded with spoils, decided to leave the blockade at the end of September, and return to Constantinople.[2]

With the help of the Ottomans, the French had managed to take strong positions on the island and finally occupied it almost completely by the end of the summer, to the dismay of Cosimo de' Medici and the Papacy.[2]

With the Ottoman fleet gone for the winter and the French fleet having returned to Marseilles, the occupation of Corsica was jeopardised.[2] Only 5,000 old soldiers remained on the island, together with the Corsican insurgents.[2]

Genoese counter-attack (1553–1554)

Henry II started negotiations with Genoa in November,[2] but Genoa sent a force of 15,000 men with the fleet of Andrea Doria and started the long recapture of the island with the siege of Saint-Florent.[2]

An Ottoman fleet sailed in the Mediterranean under Dragut but was too late, and only sailed the coast of Naples before returning to Constantinople.[2] The French only obtained the cooperations of galliots from Algiers.[2]

Franco-Turkish operations (1555–58)

By 1555, the French had been cleared from most of the coastal cities and Doria left, but many areas remained under French control. In 1555, Jourdan des Ursins replaced de Thermes, and was named "Gouverneur et lieutenant général du roi dans l'île de Corse".

The ambassador to the Ottoman Porte Codignac had to go to the Ottoman headquarters in Persia, where they were waging a war against the Safavid Empire, in the Ottoman-Safavid War (1532–1555), to plead for the dispatch of a fleet.[2] The Turkish fleet only stood by during the siege of Calvi, and contributed little. The same inactivity took place during the siege of Bastia, which had been retaken by the Genoese.[2] The Turkish fleet sent to help was severely undermined by the plague and went home towing empty ships.

Another Ottoman fleet was sent to the Mediterranean in 1558 to strategically support France, but the fleet was delayed from joining a French fleet in Corsica near Bastia, possibly due to the failure of the commander Dragut to honour Suleiman's orders. The Ottoman fleet led an invasion of the Balearic islands instead. Suleiman would apologize in a letter to Henry at the end of the year 1558.[8][9]

The Franco-Ottoman military alliance is said to have reached its peak around 1553.[10] Finally, in the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559, the French returned Corsica to Genoa.

Gallery

Paul de Thermes, Commander of the French forces

Paul de Thermes, Commander of the French forces Koja Sinan Pasha, Commander of the Ottoman forces

Koja Sinan Pasha, Commander of the Ottoman forces Baron de la Garde, Admiral of the French fleet

Baron de la Garde, Admiral of the French fleet Andrea Doria, Commander of the Genoese forces

Andrea Doria, Commander of the Genoese forces_1_JPG.jpg) Statue of Sampiero Corso at Bastelica. He combined with the French and the Ottomans to occupy Corsica

Statue of Sampiero Corso at Bastelica. He combined with the French and the Ottomans to occupy Corsica

See also

- Franco-Ottoman alliance

- History of Corsica

- List of Ottoman sieges and landings

Notes

- Naval Policy and Strategy in the Mediterranean: Past, Present, and Future, John B. Hattendorf, p. 17

- The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II by Fernand Braudel p.929ff

- The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 328

- Miller, p.2

- History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Ezel Kural Shaw, p. 106

- New Turkes: Dramatizing Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England, Matthew Dimmock, p. 49

- The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, Fernand Braudel, p. 928ff.

- The Papacy and the Levant Kenneth M. Setton p.696ff

- The Papacy and the Levant Kenneth M. Setton p.700ff

- New Turkes: Dramatizing Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England, Matthew Dimmock, p. 49

References

- Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis, The Cambridge History of Islam, Cambridge University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-521-29135-6

- William Miller, The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927 Routledge, 1966 ISBN 0-7146-1974-4