Northumberland Avenue

Northumberland Avenue is a street in the City of Westminster, Central London, running from Trafalgar Square in the west to the Thames Embankment in the east. The road was built on the site of Northumberland House, the London home of the Percy family, the Dukes of Northumberland between 1874 and 1876, and on part of the parallel Northumberland Street.

When built, the street was designed for luxury accommodation, including the seven-storey Grand Hotel, the Victoria and the Metropole. The Playhouse Theatre opened in 1882 and become a significant venue in London. From the 1930s onwards, hotels disappeared from Northumberland Avenue and were replaced by offices used by departments of the British Government, including the War Office and Air Ministry, later the Ministry of Defence. The street has been commemorated in the Sherlock Holmes novels including The Hound of the Baskervilles, and is a square on the British Monopoly board.

Location

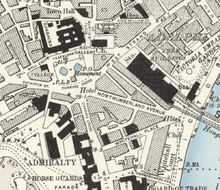

The street is around 0.2 miles (320 m) long and part of the A400, a local road connecting Westminster to Camden Town. It runs from Trafalgar Square eastwards towards the Thames Embankment. At the eastern end are the Whitehall Gardens and the Golden Jubilee Bridges over the River Thames.[2]

The nearest tube stations are Charing Cross and Embankment, and numerous bus routes serve the western end of the street.[3]

History

.jpg)

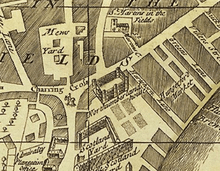

The area which is now occupied by Northumberland Avenue was originally called Hartshorn Lane. It was formed around 1491 after the Abbott of Westminster granted land to the grocer, Thomas Walker, including an inn known as the Christopher and stables. The land was sold to Humfrey Cooke in 1516, then to John Russell in 1531. In 1546, it was sold back to Henry VIII.[4]

In 1608–09, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton built a house on the eastern side of the former Chapel and Hospital of St. Mary Rounceval, at Charing Cross, including gardens running to the River Thames and adjoining Scotland Yard to the west.[5] The estate became the property of Algernon Percy, 10th Earl of Northumberland when he married Howard's great-great niece, Lady Elizabeth, in 1642, whereupon it was known as Northumberland House. In turn, the street was named Northumberland Street.[5] The house was damaged in the Wilkes' election riots of 1768, but was saved after its owner, Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland opened the nearby Ship Ale House, driving off rioters.[5]

By the 18th century, Northumberland Street was primarily used as a thoroughfare between markets in the West End of London and the wharfs along the Thames. In 1720, historian John Strype wrote that Northumberland Street was "much clogged and pestered with Carts repairing to the Wharfs".[4]

In June 1874, the whole of Northumberland House was purchased by the Metropolitan Board of Works and demolished to form Northumberland Avenue, which would accommodate hotels.[5][6] Contemporary planning permissions forbade hotels to be taller than the width of the road they were on; consequently Northumberland Avenue was built with a wide carriageway.[6] Part of the parallel Northumberland Street was demolished in order to make way for the avenue's eastern end.[4] The street was open by 1876.[7] The hotels were popular for American visitors as they were near to the West End, government buildings on Whitehall and all the mainline stations.[8]

By the 1930s, accommodation on Park Lane and Piccadilly was more popular, leading to closures on Northumberland Avenue. The seven floor Grand Hotel at No. 8 became a retail headquarters.[6] It is now an events venue for corporations including Marks & Spencer.[9] The venue is the first in Europe to install amBX lighting.[10]

Properties

Several British government departments have been located in buildings on Northumberland Avenue; the Ministry of Defence and the Air Ministry formerly occupied the triangular-shaped Hotel Metropole on the street.[11] Other buildings include the Nigerian High Commission at No. 9[12] and a London School of Economics halls of residence.[2]

The Playhouse Theatre on Northumberland Avenue was built by Sefton Parry and opened in 1882 as the Avenue Theatre. George Alexander produced his first play here. In 1905, the theatre was destroyed after part of Charing Cross Station fell on it, and was rebuilt two years later. Alec Guinness first performed on stage at the theatre. It was used for BBC broadcasts from 1951 to 1975, broadcasting radio comedies such as The Goon Show and several sessions by the Beatles.[13][14]

The Grand Hotel was built between 1882 and 1887. It had seven floors, 500 rooms and a large ballroom which has largely survived intact from its original design. The original reception room was renamed the Mayflower Room in 1923, and is now called the Salon. Unlike other hotels on Northumberland Avenue that were taken over by the War Office, the Grand has survived as an entertainment and exhibition venue.[15]

The Hotel Metropole was designed by Frederick Gordon and constructed between 1883 and 1885.[16] Prince Albert, later King Edward VII, was a regular visitor to the hotel, entertaining guests in its Royal Suite.[17] It had become one of the most popular hotels in London by the turn of the 20th century, being described by the War Office in 1914 as "of world-wide reputation", and was the original location of the Aero Club and Alpine Club.[18] In 1936, it was leased to the Government for £300,000 (now £20,500,000) to provide temporary accommodation for various departments.[19] During World War II, room 424 was used as the headquarters of MI9, the principal section of military intelligence supporting Allied prisoners of war.[20] The hotel continued to be operated as a government building after the war, and began to be used by the Air Ministry in 1951.[21] The building was sold by the Crown Estates in 2007 and reopened in 2011 as part of the Corinthia Hotel London.[22][23]

The Hotel Victoria opened in 1887, its name commemorating the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria held that year. It held 500 bedrooms and was the second largest hotel in London of its type on opening, overrunning its budget by around £520,000 (now £49,300,000).[24] The hotel was self-powered, generating its own electricity from dynamos. It was bought by Frederick Gordon in 1893, giving him a monopoly on all hotels on Northumberland Avenue.[25] A refurbishment was started in 1911, though delayed due to the First World War, which resulted in a new annexe, the Edward VII Rooms. It closed in 1940 and was used by the War Office in need of extra accommodation. The War Office bought the building outright in 1951, renaming it the Victoria Buildings. It was subsequently renamed Northumberland House.[26]

Thomas Edison's British headquarters, Edison House, was situated on the road. Several prominent personalities of the late 19th century had their voices recorded there by phonograph, including Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone and poet Robert Browning.[27] Mary Helen Ferguson, the first English female audio typist, worked at Edison House and supervised all musical recordings.[28] In 1890, retired military trumpeter Martin Lanfried recorded at Edison House using a bugle he believed to have been sounded at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and the Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854.[29]

The Royal Commonwealth Society was at No. 18 Northumberland Avenue.[7] It was founded in 1868 as the Colonial Society to improve relationships with colonies in the British Empire including Canada and Australia, and moved to its Northumberland Avenue premises in 1885. The current name dates from 1958, reflecting the change from the Empire to the Commonwealth of Nations. It is now a hotel. The Commonwealth Club opened on the premises in 1998 and features the only suspended glass dining room in London.[30] The Royal African Society was based at the same location, before moving to the School of Oriental and African Studies in Russell Square.[7]

Cultural references

Northumberland Avenue is referenced several times in Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes novels, including The Greek Interpreter and The Hound of the Baskervilles. The stories refer to wealthy Oriental visitors staying in hotels along the avenue, including the Grand, the Metropole and the Victoria.[31] The Northumberland Arms, at the junction of Northumberland Street and Northumberland Avenue, a public house, was renamed the Sherlock Holmes in 1957, and contains numerous Holmes-related exhibits from the 1951 Festival of London.[32]

The street is part of a group of three on the London Monopoly board, with Pall Mall and Whitehall. All three streets connect at Trafalgar Square.[33]

Northumberland Avenue formed part of the marathon course of the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.[34] The women's Olympic marathon took place on 5 August and the men's Olympic marathon on 12 August, with the Paralympics following on 9 September.[35][36]

See also

References

Citations

- Rebecca Cloke (6 September 2011), Trees and the Public Realm, City of Westminster, p. 20 in appendix B

- "Northumberland Avenue". Google Maps. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- "Buses nearby: Northumberland Avenue". TfL. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Gater, G H; Wheeler, E P, eds. (1937). "Northumberland Street". Survey of London. London. 18, St Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand: 21–26. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Gater, G H; Wheeler, E P, eds. (1937). "Northumberland House". Survey of London. London. 18, St Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand: 10–20. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Moore 2003, p. 53.

- Weinreb et al 2008, p. 593.

- MOD 2001, p. 17.

- Marlow, Ben (8 July 2015). "M&S cannot afford to party on this set of results". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- Colston, Paul (15 March 2013). "8 Northumberland Avenue adds new lighting system to Victorian Ballroom". Conference News. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- MOD 2001, pp. 16,23.

- "Nigeria High Commission". Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Moore 2003, p. 54.

- Weinreb et al 2008, p. 647.

- "A short history of 8 Northumberland Avenue" (PDF). 8, Northumberland Avenue. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- MOD 2001, p. 20.

- MOD 2001, p. 22.

- MOD 2001, p. 21.

- MOD 2001, pp. 22–23.

- John Nichol, Tony Rennell (2008). Home Run: Escape from Nazi Europe. Penguin. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-141-02419-6.

- MOD 2001, p. 23.

- David Lindsay (28 April 2009). "IHI consortium purchases London hotel for €174m". Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- Walsh, Dominic (29 April 2009). "Metropole Hotel set for £135m luxury revamp". The Times. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- MOD 2001, pp. 17–18.

- MOD 2001, p. 18.

- MOD 2001, pp. 18,19.

- Jonnes 2009, p. 92.

- John 2012, Footnote on pp. 36–37.

- Dutton 2007, p. 307.

- Weinreb et al 2008, p. 716.

- Wheeler 2011, p. 291.

- Glinert 2012, p. 292.

- Moore 2003, p. 45.

- "2012 Olympics : Central London road closures". LBC. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "marathon men results – Athletics – London 2012 Olympics". london2012.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

- "marathon women results – Athletics – London 2012 Olympics". london2012.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

Sources

- Dutton, Roy (2007). Forgotten Heroes: The Charge of the Light Brigade. Infodial. ISBN 978-0-955-65540-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glinert, Ed (2012). The London Compendium. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-718-19204-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- John, Juliet (2012). Dickens and Modernity. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-843-84326-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jonnes, Jill (2009). Eiffel's Tower: The Thrilling Story Behind Paris's Beloved Monument and the Extraordinary World's Fair That Introduced It. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-05251-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-43386-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2008). The London Encyclopedia. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

- Wheeler, Thomas Bruce (2011). The London of Sherlock Holmes. Andrews. ISBN 978-1-780-92211-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Old War Office Buildings – A History" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. 2001: 16, 18–19. Retrieved 20 January 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northumberland Avenue. |