Rebadging

Badge engineering, sometimes called rebadging, is the practice of applying a different badge or trademark (brand, logo or manufacturer's name/make/marque) to an existing product (e.g., an automobile) and subsequently marketing the variant as a distinct product.[1][2] Due to the high cost of designing and engineering a new model or establishing a brand (which may take many years to gain acceptance), economies of scale make it less expensive[3] to rebadge a product once or multiple times than to create different models.

The term badge engineering is an intentionally ironic misnomer, in that little or no actual engineering takes place.[4][5]

The term originated with the practice of replacing an automobile's emblems to create an ostensibly new model sold by a different maker. Changes may be confined to swapping badges and emblems, or may encompass minor styling differences, as with cosmetic changes to headlights, tail lights, front and rear fascias and outer body skins. More extreme examples involve differing engines and drivetrains. The term badge engineered does not apply to vehicles that share a common platform architecture but are uniquely designed so that they may look completely different from each other. This is achieved by not sharing visible parts, and maintaining a host of underlying parts specific to their respective applications.

Although platform sharing often involves rebadging, it also often extends much further than that, as an automobile platform may be used with many different applications; for example, using a single platform as the basis for sedan and crossover model variations.

Rebadging in the automotive industry can be compared with white-label products in other consumer goods industries, such as consumer electronics and power tools.

Rebadging may also be applied to services. For example, commercial airlines practice a type of service rebadging known as codesharing.

History

The first case of badge engineering appeared in 1917 with the Texan automobile assembled in Fort Worth, Texas, that made use of Elcar bodies made in Elkhart, Indiana.[6][7]

"Probably the industry's first example of one car becoming another" occurred in 1926 when Nash Motors' newly introduced smaller-sized Ajax models were discontinued in 1926 after over 22,000 Ajax cars were sold during the brand's inaugural year.[8] The chairman and CEO of the company, Charles W. Nash, ordered that the Ajax models be marketed as the "Nash Light Six", Nash being a known and respected automobile brand.[9] Production was stopped for two days so Nash emblems, hubcaps and radiator shells could be exchanged on all unshipped Ajax cars.[8] Conversion kits were also distributed at no charge to Ajax owners to transform their cars and protect the investment they had made in purchasing an automobile made by Nash.[10]

- 1925 Nash

1926 Ajax

1926 Ajax

Starting with the beginning of General Motors in 1923, chassis and platforms were shared with all brands. GMC, which historically was a truck builder, began to offer their products branded as Chevrolet, and vehicles produced by GM were built on common platforms shared with Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac. Exterior appearances were gradually upgraded between these vehicle brands. For 1958, GM was promoting their fiftieth year of production, and introduced Anniversary models for each brand; Cadillac, Buick[11], Oldsmobile, Pontiac, and Chevrolet. The 1958 models shared a common appearance on the top models for each brand; Cadillac Eldorado Seville, Buick Roadmaster Riviera, Oldsmobile Starfire 98, Pontiac Bonneville Catalina, and the Chevrolet Bel-Air Impala.

1958 Chevrolet Bel Air Impala Convertible

1958 Chevrolet Bel Air Impala Convertible- 1958 Pontiac Bonneville

1958 Oldsmobile 98 Convertible

1958 Oldsmobile 98 Convertible 1958 Buick Roadmaster Riviera

1958 Buick Roadmaster Riviera- 1958 Cadillac Eldorado

A later example was Wolseley Motors after it was bought out by William Morris. After World War I, the "Wolseley started to lose its identity and eventually succumbed to badge engineering."[12] This was repeated with the consolidation of Austin Motor Company and the Nuffield Organisation (parent company of Morris Motors) to form the British Motor Corporation (BMC). The rationalization of production to gain efficiencies "did not extend to marketing" and each "model was adapted, by variation in trim and accessories, to appeal to customer loyalties for whom the badge denoting the company of origin was an important selling advantage ... 'Badge Engineering', as it became known, was symptomatic of a policy of sales competition between the constituent organizations."[13] The ultimate example of BMC badge engineering was the 1962 BMC ADO16 which was available badged as a Morris, MG, Austin, Wolseley, Riley and the upmarket Vanden Plas. A year earlier the Mini was also available as Austin, Morris, Riley and Wolseley - the latter two having slighty bigger boots.

Examples

Regional brands

Badge engineering often occurs when an individual manufacturer, such as General Motors, owns a portfolio of different brands, and markets the same car under a different brand. It may be done to expand the ranges of different brands in one market without developing completely new models, such as selling one car as a Chevrolet, a GMC and a Cadillac by GM in the United States; for example, the Chevrolet Tahoe, GMC Yukon and the Cadillac Escalade.

It may also be done to sell the same model in different regions and markets simply under a different name. For example, cars built by Daewoo, now owned by GM, are no longer badged as Daewoos. Instead, they are now badged as Chevrolets. Similarly, in Australia and New Zealand, where Daewoo was unsuccessful, they were rebadged as Holden models. The Australian car manufacturing industry experienced major badge reengineering during the 1980s and 1990s as part of the failed Button car plan.

Brand expansion

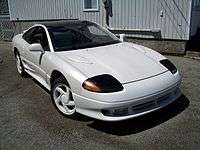

Another way badge engineering may occur is when two separate companies trade off products that each brand lacks in its line-up. A prime example of this would be the first-generation Honda Odyssey being rebadged as an Isuzu Oasis because Isuzu needed a minivan, while the Isuzu Rodeo was rebadged as the Honda Passport because Honda had the need for an SUV. Another example is the Mitsubishi GTO/3000GT, which was sold as the Dodge Stealth in the North American market. Vauxhall/Opel used badge-engineering for many years for their entire range of medium commercial vehicles, selling several models of Renault vans.

Japanese distribution networks

In Japan, Toyota, Nissan, and Honda used this approach to expand vehicle production by offering one car at multiple Japanese dealerships. Toyota took the Corolla, which was exclusive to Toyota Corolla Store locations and sold it as the Toyota Sprinter, which was exclusive to Toyota Auto Store locations. Nissan followed suit with the Nissan Cedric, and sold an identical bodystyle of the Cedric, called the Nissan Gloria, and sold the Cedric at Nissan Bluebird Store, while the Gloria was sold at Nissan Prince Store. Honda also pursued this marketing approach with the Honda Accord, sold in 1984 at Honda Clio locations and sold it as the Honda Vigor at Honda Verno locations. The difference to this method, as opposed to the North American and European implementation of selling one product under different brand names with minor changes to exterior bodywork, is that the Japanese sold the same car under the same brand name, but with a different model name.

Joint ventures

Two different automakers can also pool resources by operating a joint venture to create a product, then selling it each as their own. For instance, General Motors and Toyota formed NUMMI. The vehicles produced from this venture (though not necessarily at NUMMI itself) included the Toyota Sprinter/Chevrolet Prizm, and later the Toyota Matrix/Pontiac Vibe.

Another example was the cooperative work between Volkswagen and Ford to create the VW Sharan, Ford Galaxy and SEAT Alhambra.

Badge engineering may occur when one company allows another, otherwise unaffiliated, company to market a revised version of their product, as with Volkswagen marketing a re-skinned version of the Dodge Caravan or Chrysler Town and Country as the Volkswagen Routan. Another example was the joint venture of Mitsubishi and Chrysler that resulted in vehicles produced by Diamond-Star Motors that were marketed under various nameplates.

Luxury vehicles

Badge engineering occurs in the luxury-type market segments. An automobile manufacturer will use a model from its mainstream brand, upgrade it with more features, technology, luxury and/or style, then market it as a more expensive model under a premium marque. The luxury models may have more than just cosmetic differences; they may receive improved engines and drivetrains.

An example of this is that the Ford Motor Company took its well-known Ford Fusion, and sold it as the Lincoln MKZ, or the Ford Expedition being sold as the Lincoln Navigator. Another example is General Motors rebadging the Chevrolet Tahoe, a shorter version of the Suburban, as the Cadillac Escalade and GMC Yukon. An example of "Fake Prestige" was the Cygnet city car marketed by Aston Martin, with a price of more than $45,000 in its most basic version, but the vehicle was actually the Toyota iQ and, except for the Cygnet's special trim and special luggage set, sold for $17,000.[2][14][15]

The business strategy of Volkswagen is to standardize platforms, components, and technologies, thus improving the firm's profitability and growth.[16] For example, Audi uses components from their more pedestrian counterparts, sold as Volkswagen Group's mass-market brands.[17] As an effort to place Audi as a "premium" marque, Volkswagen introduces new technologies in Audi-branded cars before fitting them to mainstream products (such as the Direct-Shift Gearbox). Nevertheless, Volkswagen uses platform sharing extensively. For example, the basic A platform underpins the Golf, Jetta, New Beetle, Audi TT and A3, SEAT Leon and Toledo, as well as the Škoda Octavia, while the "top end" D platform served the VW Phaeton and Bentley Continental GT in steel form, and the Audi A8 in aluminum form during the 2000s.[18]

Japanese carmakers have followed this practice of rebadging as well, such as Honda's Acura line, Nissan's Infiniti brand, and Toyota's Lexus marque, as the entry-level luxury models were based on their mainstream lineup. For example, the Lexus ES shares the drivetrain and is based on the same platform as the Toyota Camry[19] (and from the 2013 model year, on the stretched version used by the Avalon[20]); the Lexus LX is an upgraded rebadge of the Toyota Land Cruiser, and the Acura TSX is a rebadge of the JDM Honda Accord.

Problems and controversy

Although intended to save development costs by spreading design and research costs over several vehicles, excessive badge engineering can be problematic if not implemented properly. Having multiple car brands can greatly increase selling cost, as each brand must be marketed separately and often requires its own dealership network. Badge engineering can also hurt overall sales by resulting in "cannibalism" between two or more brands owned by the same company, by failing to develop a distinct image for each brand, or by allowing the failure of one version of a model to carry over to its rebadged "siblings." The discontinuation of the Eagle brand sold by Chrysler is attributed to it being crowded out by the company's other more established divisions and the failure to effectively incorporate the new marque into Chrysler's dealer network.

Badge engineering of vehicles from another manufacturer or subsidiary of the same manufacturer may also confuse and disappoint unwitting consumers who purchase a certain brand of vehicle expecting certain characteristics in terms of engineering, reliability and design along with national origin. If one or more of those qualities are not met, it can lead to consumer dissatisfaction plus impacted brand image for the brand that rebadged the vehicle. In an unusual case of engine badge engineering, General Motors lost a lawsuit in 1981 after consumers bought 1977 Oldsmobile Delta 88s equipped with a Chevrolet small-block engine instead of the expected Oldsmobile V8 engine. Some of the Chevrolet-built engines were marked "Oldsmobile," with the substitution occurring because GM increased production of V6 engines preparing for another oil crisis and severely underestimated the demand for the Oldsmobile V8. At the time, Oldsmobile was engaged in marketing touting the unique qualities of the Oldsmobile "Rocket" V8 and the state of Illinois filed a lawsuit on behalf of buyers claiming false advertising. GM stated that both engines, of differing design, had similar durability, performance and reliability characteristics with one another and a lawyer for GM stated that a brand name on a vehicle "[does not mean] it had made all the parts." [21], but ended up settling with buyers of those vehicles[22] and furthermore, GM discontinued their policy of linking engines with a certain division.[22] The Rover CityRover, launched in 2003 as the last vehicle from the MG Rover Group, was a rebadged Tata Indica made in India. English motoring journalist George Fowler criticized the MG Rover Group, who was enjoying national sympathy from the British public as the last domestically-owned automobile manufacturer, stating the CityRover was "a duplicitous attempt to 'save Rover' by flogging an Indian car on which the only Rover bits were the badges."[23]

Origins of General Motors' badge engineering dates back to the early 1970s when the Chevrolet Nova compact was rebadged by the upscale Buick Apollo (Skylark after 1975), Oldsmobile (Omega), and Pontiac (Ventura II and Phoenix) divisions as entry-level cars. The 1973 oil embargo resulted in GM corporatizing their X and H platform automobiles into its entry-level products by its respective divisions in the United States and Canada. A decade earlier, GM of Canada (prior to the 1965 Auto Pact) marketed the Acadian and Beaumont as standalone marques where two Chevrolet vehicles (Chevy II and Chevelle) were facelifted and marketed under a standalone marque (and sold via existing Canadian Buick and Pontiac dealerships alongside the Envoy (rebadged Vauxhalls sourced from the UK sold as captives)) until the passage of Auto Pact. The Acadian and Beaumont, which were based on a Chevrolet model and built with Canadian content (e.g. the Beaumont having the interior of a Pontiac LeMans in lieu of the one sourced from the Chevelle) since GM Canada did not offer the GM Y platform compacts (1960-64 Buick-Olds-Pontiac) because of import tariffs.

By the late 1970s, GM's downsized B-, C- and D-platform cars set the standard of the inevitable when badge engineering and platform sharing were fused together to trim excess production expenditures--similar-looking bodystyles with distinctive appearances which was a trend throughout the 1980s. This trend continued with subsequent platforms from the J-car to its redesigned front-wheel drive full-size sedans - later to include minivans, SUVs, and crossovers e.g. minivan versions of the GM10 platform (Lumina APV, Trans Sport, Silhouette) along with the Oldsmobile Bravada (an upscale variant of the S10 Blazer and Jimmy) which was a competitor to the upscale variants of the Explorer (Mercury Mountaineer, Lincoln Aviator) and Jeep Cherokee/Grand Cherokee.

The ill-received Cadillac Cimarron is one of the most widely cited examples of problems with badge engineering. The car was essentially identical to the Chevrolet Cavalier except for cosmetic differences, which resulted in poor sales, as the company found few buyers willing to pay nearly twice as much for a car that offered little more than the Cavalier. The J-platform which the two vehicles were based on was also largely engineered by GM's German subsidiary, Opel (who marketed the vehicle in Europe as either the Opel Ascona or Vauxhall Cavalier). This resulted in damage to the Cadillac brand image. Other manufacturers have given badge-engineered cars distinct branding and style, high-quality interior materials, wide range of convenience features and performance powertrains, as these are key to distinguishing them from mass-market equivalents and making these appeal to consumers; successful luxury cars following this formula include the Lexus ES, Acura TL, and Audi A3.[24][25][26] For Toyota, "Camry's reliability and quality - and Lexus' dealership experience" helped the Lexus ES succeed in the market, but it reinforced negative connotations of Lexus vehicles being largely more upmarket Toyotas.[27]

.jpg)

Ford Motor Company followed suit where for decades its Ford branded vehicle lineup in North America had a Mercury twin when sold via Lincoln-Mercury dealerships which were considered upscale variants - the Lincoln Versailles (introduced as an answer to the Cadillac Seville and Chrysler LeBaron, replacing its Mercury Grand Monarch Ghia) shared its body panels with the Granada/Monarch product lineup until the 1979 model year where the C pillar roofline was restyled. Upon the introduction of its Fox platform replacement which shared no exterior body panels, the 1982 Lincoln Continental was again marketed as a Seville competitor but resulted in shifting the nameplate of its full-sized counterpart to the mid-sized market. The Lincoln Navigator, derived from the Ford Expedition, proved very successful. However, the Ford Explorer-based Lincoln Aviator failed. The fact that the Aviator was virtually identical to the Navigator in all regards but size made it difficult to generate attention among potential buyers, and the Mercury Mountaineer had already proved sufficient to cater to buyers wanting a slightly more upscale alternative to the Explorer.

As the U.S. entered into a recession, the Big Three automakers discontinued brand divisions as a cost-cutting measure. General Motors discontinued the Pontiac and Saturn models in 2010 (which was done earlier when the Oldsmobile brand disappeared in 2004), and Ford sold its Volvo division (which was previously a separate carmaker in its own right) to the Chinese manufacturer Geely Automobile (after it had sold its other luxury brands of Jaguar, Land Rover, and Aston Martin). Its Mercury brand was also phased out in December 2010.

Models produced under licence

A variant on rebadging is licensing models to be produced by other companies, typically in another country. The earliest such vehicle was the Austin 7 (1922 - 1939), designed and built by Austin Motor Company and licensed to other manufacturers across continents that became their first ever model. The Bantam in the US that would eventually build the first Jeep, BMW in Germany, and Nissan in Japan.

Among the post-war cars, the Fiat 124 designed and built by Fiat, Italy was licensed to various other manufacturers from different countries and became a dominant car on roads in many Eastern Europe and West Asian countries.

.jpg)

The Morris Oxford Series IV built by Morris of England in 1955 would become Hindustan Ambassador in India and was manufactured until 2014. Another example of this is the British Hillman Hunter, which was license-built in Iran as the Paykan, as well as Naza, building vehicles under license from Kia and Peugeot (Naza 206 Bestari).

A similar example of licensed badge-engineered products would be the Volga Siber, a rebadged version of the Chrysler Sebring sedan and the Dodge Stratus sedan produced in Russia from 2008-2010.

See also

References

- Chambers, Cliff (4 November 2011). "What is badge engineering?". motoring.com.au. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Fingleton, Eamonn (7 April 2013). "Same Car, Different Brand, Hugely Higher Price: Why Pay An Extra $30,000 For Fake Prestige?". Forbes. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Sedgwick, David (4 August 2014). "Carmakers bet on big global platforms to cut costs". Automotive News. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Orlove, Raphael (3 May 2014). "The Ten Best Examples Of Badge Engineering". Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Martin, Murilee. "Badge Engineering". The Truth About Cars. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Locke, William S. (2007). Elcar and pratt automobiles: the complete history. Mcfarland. p. 53. ISBN 9780786432547. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

The Texas Motor Car Association had started building Elcars into their own Texan automobiles before the Great War

- Locke, p. 320. "The Texan automobile used Elcars with 'badge engineering'"

- Kimes, Beverly R.; Clark, Jr., Henry A., eds. (1996). Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942. Krause Publications. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-87341-428-9. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Lewis, Albert L.; Musciano, Walter A. (1977). Automobiles of the World. Simon and Schuster. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-671-22485-1.

- "Nash Motors cars, 1916 to 1954". Allpar com. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "1958 Buick Convertible Poster". GMPhotoStore.

- Smith, Bill (2005). Armstrong Siddeley Motors: The Cars, the Company and the People in Definitive Detail. Veloce Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-904788-36-2.

- Church, Roy A. (2004). The rise and decline of the British motor industry. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-55770-2.

- Meiners, Jens (December 2009). "2011 Aston Martin Cygnet The only Aston with a CVT". Car and Driver. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Estrada, Zac (10 January 2013). "The Aston Martin Cygnet Is Dead And Now We Want One". jalopnik. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Seabaugh, Christian (20 December 2011). "Volkswagen Parts, Platform Sharing to Intensify Across Brands". Motor Trend. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Cunningham, Wayne (2 February 2012). "New platform brings Volkswagen and Audi models closer". CNET. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

Volkswagen developed its MQB, or Modular Transverse Matrix, platform to improve manufacturing efficiency. Volkswagen, Audi, Seat, and Skoda models will be built on the MQB platform

- Csere, Csaba (June 2003). "Platform Sharing for Dummies". Car and Driver. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Elias, Mark (6 November 2012). "First Drive: 2013 Toyota Avalon [Review]". Left Lane News. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

The new Avalon shares powertrains and platforms with its little sister, the Toyota Camry, and its cousin, the Lexus ES 350.

- Shenhar, Gabe (27 June 2012). "First drive: 2013 Le xus ES attempts to spice up its upscale sedan recipe". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

For 2013, Toyota is bringing out a new iteration of its popular Lexus ES, that upscale relative of the Toyota Camry... Based on the rejuvenated and improved 2012 Camry platform, the ES350 remains about the same size but has added nearly two inches to the wheelbase.

- Stuart, Reginald. "G.M. Calls Its Engine Swapping Innocent, But to the Brand‐Faithful Buyer It's a Sin". New York Times. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "Jury Orders G.M. to Pay 10,000 in Switch of Engines". New York Times. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Fowler, George (2016). Car-tastrophes: 80 Automotive Atrocities from the past 20 years. Veloce. p. 93. ISBN 1845849337.

- Frechette, Gerry (21 June 2010). "Test Drive: 2010 Audi A3 TDI - Autos.ca". Autos Canada. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Flammang, Jim (22 June 2005). "2006 Audi A3 Review". Cars.com. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Proudfoot, Dan (29 April 2010). "Audi luxury compact is ready for the future". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- MacKenzie, Angus (November 2011). "The Big Picture: Saving Lexus - Toyota's luxury brand needs an overhaul". Motor Trend. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)