Suicide methods

A suicide method is any means by which people attempt suicide, purposely ending their lives. People who attempt suicide and survive may experience serious injuries, such as broken bones or brain injury.[1] These injuries can have long-term effects on their health.[1]

| Suicide |

|---|

|

Social aspects |

|

Related phenomena |

|

Organizations |

Some of the ways to prevent suicides include making methods less accessible such as removing guns from the home of an at-risk person, policies that address the misuse of alcohol, and treatment of mental disorders.[2]

Purpose of studying suicide methods

The academic study of suicide methods aims to identify common methods of suicide and groups at risk of suicide, since making methods less accessible may be useful in preventing suicides.[3][4][5] This information allows public health resources to focus on the problems that are relevant in a particular place, or for a given population or subpopulation. For instance, if firearms are used in a significant number of suicides in one place, then public health policies there could focus on gun safety, such as keeping guns locked away, and the key inaccessible to at-risk family members. If young people are found to be at increased risk of suicide by overdosing on particular medications, then an alternative class of medication may be prescribed instead, a safety plan and monitoring of medication can be put in place, and parents can be educated about how to prevent the hoarding of medication for a future suicide attempt.[5]

Cutting

Suicide by cutting might involve bleeding, infarction, sepsis, or drowning from a lung contusion. Significant bleeding is usually the result of damage to arteries. Initial cuts may be shallow, referred to as hesitation wounds or tentative wounds. They are often non-lethal, multiple parallel cuts.[6] While cutting is relatively common it only makes up 1% of deaths by suicide in the United States.[7]

Wrist cutting

Wrist cutting is sometimes practiced with the goal of self-harm rather than suicide; however, if the bleeding is sufficient death may occur.[8]

In the case of a non-fatal suicide attempt, the person may experience injury of the tendons, or the ulnar and median nerves which control the muscles of the hand, both of which can result in temporary or permanent reduction in the person's sensory or motor ability or result in chronic pain.[9]

Dehydration

Death from dehydration can take from several days to a few weeks. This means that unlike many other suicide methods, it cannot be accomplished impulsively. Those who die by terminal dehydration typically lapse into unconsciousness before death, and may also experience delirium and deranged serum sodium.[10] Discontinuation of hydration does not produce true thirst, although a sensation of dryness of the mouth often is reported as "thirst." The evidence that this is not true thirst is extensive and shows the ill feeling is not relieved by giving fluids intravenously, but is relieved by wetting the tongue and lips and proper care of the mouth. Patients with edema tend to take longer to die of dehydration because of the excess fluid in their bodies.[11]

Terminal dehydration has been described as having substantial advantages over physician-assisted suicide with respect to self-determination, access, professional integrity, and social implications. Specifically, a patient has a right to refuse treatment and it would be a personal assault for someone to force water on a patient, but such is not the case if a doctor merely refuses to provide lethal medication.[12] But it also has distinctive drawbacks as a humane means of voluntary death.[13] One survey of hospice nurses found that nearly twice as many had cared for patients who chose voluntary refusal of food and fluids to hasten death as had cared for patients who chose physician-assisted suicide.[14] They also rated fasting and dehydration as causing less suffering and pain and being more peaceful than physician-assisted suicide.[15] Other sources, however, have noted very painful side effects of dehydration, including seizures, skin cracking and bleeding, blindness, nausea, vomiting, cramping and severe headaches.[16] There can be a fine line between terminal sedation that results in death by dehydration and euthanasia.[17]

Disease

There have been documented cases of deliberately trying to contract a disease such as HIV/AIDS as a means of suicide.[18][19][20]

Drowning

Suicide by drowning is the act of deliberately submerging oneself in water or other liquid to prevent breathing and deprive the brain of oxygen. It accounts for less than 2% of all suicides in the United States.[21] Of those who attempt suicide by drowning 56% die.[22]

Due to the body's natural tendency to come up for air, drowning attempts often involve the use of a heavy object to overcome this reflex. As the level of carbon dioxide in the person's blood rises, the central nervous system sends the respiratory muscles an involuntary signal to contract, and the person breathes in water. Death usually occurs as the level of oxygen becomes too low to sustain the brain cells.

Electrocution

Suicide by electrocution involves using a lethal electric shock to kill oneself. This causes arrhythmias of the heart, meaning that the heart does not contract in synchrony between the different chambers, essentially causing elimination of blood flow. Furthermore, depending on the current, burns may also occur. In his opinion outlawing the electric chair as a method of execution, Justice William M. Connolly of the Nebraska Supreme Court stated that "electrocution inflicts intense pain and agonizing suffering", adding that it is “unnecessarily cruel in its purposeless infliction of physical violence and mutilation of the prisoner’s body.”[23] Contact with 20 mA of current can result in death.[24]

Fire

Immolation usually refers to suicide by fire. It has been used as a protest tactic, most famously by Thích Quảng Đức in 1963 to protest the South Vietnamese government's systematic anti-Buddhist, pro-Catholic policies; by Malachi Ritscher in 2006 to protest the United States' involvement in the Iraq War; and by Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia which started the Tunisian Revolution in 2011 and the Arab Spring.

Self-immolation was also carried out as a ritual known as sati in certain parts of India, where a Hindu wife immolated herself in her dead husband's funeral pyre, either voluntarily or by coercion.[25]

The Latin root of "immolate" means "sacrifice", and is not restricted to the use of fire, though in common US media usage the term immolation refers to suicide by fire.

This method of suicide is relatively rare due to the long and painful experience one has to go through before death sets in. This is also contributed to by the ever-present risk that the fire be extinguished before death sets in, and in that way causes one to live with severe burnings, scar tissue, and the emotional impact of such injuries.

Volcano

Suicide by volcano involves jumping into molten lava in an active volcanic crater, fissure vent, lava flow or lava lake. The actual cause of death may be as a result of the fall (see jumping from height), contact burns, radiant heat or asphyxiation from volcanic gases. According to some ancient sources, philosopher Empedocles jumped into the Aetna trying to make everybody believe that he had disappeared from the Earth to become a god; this was frustrated when the volcano spat out one of his bronze sandals. Modern suicides have taken place in numerous volcanoes, but the most famous is Mount Mihara in Japan. In 1933, Kiyoko Matsumoto completed suicide by jumping into the Mihara crater. A trend of copycat suicides followed, as 944 people jumped into the same crater over the following year.[26] Over 1,200 people attempted suicide in two years before a barrier was erected.[27] The original barrier was replaced with a higher fence topped with barbed wire after another 619 people jumped in 1936.[28][29]

Firearm

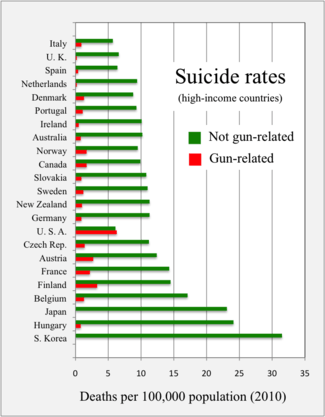

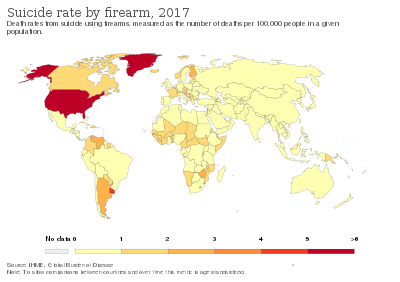

In the United States firearm are used in less than 5% of attempts but result in death about 90% of the time.[22] They are thus the leading cause of death by suicide as of 2017 in the United States.[32] Generally, the bullet will be aimed at point-blank range, often at the temple or, less commonly, into the mouth, under the chin or at the chest. Worldwide, firearm prevalence in suicides varies widely, depending on the acceptance and availability of firearms in a culture. The use of firearms in suicides ranges from less than 10% in Australia[33] to 50.5% in the U.S., where it is the most common method of suicide.[34]

Surviving a self-inflicted gunshot may result in severe chronic pain for the patient as well as reduced cognitive abilities and motor function, subdural hematoma, foreign bodies in the head, pneumocephalus and cerebrospinal fluid leaks. For temporal bone directed bullets, temporal lobe abscess, meningitis, aphasia, hemianopsia, and hemiplegia are common late intracranial complications. As many as 50% of people who survive gunshot wounds directed at the temporal bone suffer facial nerve damage, usually due to a severed nerve.[35]

A positive association exists between firearm availability and increased suicide risk.[36][37][38][39] This relationship is most strongly established in the United States.[40] This association is almost certainly not due to confounding, as any confounding risk factor that could account for this association would have to meet multiple implausible criteria.[41] Those who have access to firearms as part of their profession are more likely to complete suicide through the use of a firearm — 91.5% of suicides by police officers in America involved the use of a firearm. The United States has both the highest number of suicides and firearms in circulation in a developed country and when gun ownership rises so too does suicide involving the use of a firearm.[42][43] More firearms are involved in suicide than are involved in homicides in the United States. Those who have recently purchased a firearm are found to be high risk for suicide within a week after their purchase.[44]

A 2004 report by the National Academy of Sciences found an association between estimated household firearm ownership and gun suicide rates,[45][46] though a study by two Harvard researchers did not find a statistically significant association between household firearms and gun suicide rates,[47] except in the suicides of children aged 5–14.[47] Another study found that gun prevalence rates were positively associated with suicide rates among people aged 15 to 24, and 65 to 84, but not among those aged 25 to 64.[48] Case-control studies conducted in the United States have consistently shown an association between guns in the home and increased suicide risk,[49] especially for loaded guns in the home.[50] Numerous ecological and time series studies have also shown a positive association between gun ownership rates and suicide rates.[51][52][53] This association tends to only exist for firearm-related and overall suicides, not for non-firearm suicides.[52][54][55][56] A 2013 review found that studies consistently found a relationship between gun ownership and gun-related suicides, with few exceptions.[57] A 2016 study found a positive association between gun ownership and both gun-related and overall suicides among men, but not among women; gun ownership was only strongly associated with gun-related suicides among women.[58] During the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a strong upward trend in adolescent suicides with a gun,[59] as well as a sharp overall increase in suicides among those age 75 and over.[60] A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis found that access to firearms was associated with a higher risk of suicide.[61]

In the United States, states with stricter gun laws have lower overall suicide rates.[62][63] A 2006 study found a decline in firearm-related suicides in Australia accelerated after the National Firearms Agreement was enacted there. The same study found no evidence of substitution to other methods.[64] Multiple studies in Canada found that gun suicides declined after gun control, but methods like hanging rose leading to no change in the overall rates.[65][66][67] Similarly, a study conducted in New Zealand found that gun suicides declined after more legislation, but overall suicide rates did not change.[68] A case-control study in New Zealand found that household gun ownership was associated with gun suicides, but not overall suicide.[69] A Canadian study found that gun ownership by province was not correlated to provincial overall suicide rates.[70]

Gun laws

Reducing access to guns at a population level decreases the risk of suicide by firearms.[71] The laws regulating the use, purchase, and trading of firearms are varied by state in the US.[72] The Midwest and Southeast have the least legislature regulating firearm use and purchase where there is missing or unclear legislature on gun control and the open and concealed carrying or handguns and long guns are allowed with or without a permit depending on the state. These regions correlate with the states with the highest increases of suicide rates in the past 17 years.[73]

There are certain areas in the United States where firearms are illegal entirely.[74] In 1976, the District of Columbia banned the possession, sale, transfer, and purchase of handguns by civilians. Since the prohibition of handguns homicide by handguns decreased by 25% while suicides by handgun decreased by 23% in the District of Columbia. The rates of homicide and suicide in the surrounding areas where the restrictions were not applied and noted that there was no significant change in these rates. This study has been criticized.[75]

Hanging

Attempted suicide by hanging results in death about 53% of the time.[22] It was the most common method in traditional Chinese culture,[76] as it was believed that the rage involved in such a death permitted the person's spirit to haunt and torment survivors.[77][78] It has been used as an act of revenge by women[79] and of defiance by powerless officials, who used it as a "final, but unequivocal, way of standing still against and above oppressive authorities".[76] People would often approach the act ceremonially, including the use of proper attire.[76]

When hanging oneself, the subject uses some type of ligature, as in a rope or a cord, to form a noose (or loop) around the throat, with the opposite end secured to some fixture. Depending on the placement of the noose and other factors, the subject strangles or suffers a broken neck. In the event of death, the actual cause often depends on the length of the drop; that is, the distance the subject falls before the rope goes taut.

In a "short drop", the person may die from strangulation, in which the death may result from a lack of oxygen to the brain. The person is likely to experience hypoxia, skin tingling, dizziness, vision narrowing, convulsions, shock, and acute respiratory acidosis. One or both carotid arteries and/or the jugular vein may also be compressed sufficiently to cause cerebral ischemia and a hypoxic condition in the brain which will eventually result in or contribute to death. Hanging survivors typically have severe damage to the trachea and larynx, damage to the carotid arteries, damage to the spine, and brain damage due to cerebral anoxia.

In a typical "long drop", the subject is likely to suffer one or more fractures of the cervical vertebrae, generally between the second and fifth, which may cause paralysis or death. In extremely long drops, the hanging may result in complete decapitation.

Hanging is the prevalent means of suicide in pre-industrial societies, and is more common in rural areas than in urban areas.[80] It is also a common means of suicide in situations where other materials are not readily available, such as in prisons.

Indirect suicide

Indirect suicide is the act of setting out on an obviously fatal course without directly carrying out the act upon oneself. Indirect suicide is differentiated from legally defined suicide by the fact that the actor does not pull the figurative (or literal) trigger. Examples of indirect suicide include a soldier enlisting in the army with the express intention and expectation of being killed in combat, or someone could be provoking an armed officer into using lethal force against them. The latter is generally called "suicide by cop". In some instances the subject commits a capital crime in hope of being sentenced to death.

Evidence exists for numerous examples of suicide by capital crime in colonial Australia. Convicts seeking to escape their brutal treatment would murder another individual. This was necessary due to a religious taboo against direct suicide. A person completing suicide was believed to be destined for hell, whereas a person committing murder could absolve their sins before execution. In its most extreme form, groups of prisoners on the extremely brutal penal colony of Norfolk Island would form suicide lotteries. Prisoners would draw straws with one prisoner murdering another. The remaining participants would witness the crime, and would be sent away to Sydney as capital trials could not be held on Norfolk Island, thus earning a break from the Island. There is uncertainty as to the extent of suicide lotteries. While surviving contemporary accounts claim that the practice was common, such claims are probably exaggerated.[81]

Animal attacks

Some people have chosen to indirectly bring about their death by suicide by being attacked by predatory animals such as sharks and crocodiles, and in some cases the person has been eaten alive; for example, in 2011 in eastern South Africa a depressed man (who wanted to be attacked by a crocodile) jumped into a river and was consumed by a crocodile.[82] Similarly, in 2002 a depressed woman killed herself by jumping into a crocodile pond at the Samutprakarn Crocodile Farm and Zoo in Thailand.[83] In 2014 a second woman killed herself by jumping into the same crocodile pond in Thailand.[84] Both women were eaten alive.

Jumping from height

Jumping from height is the act of jumping from high altitudes, for example, from a window (self-defenestration or auto-defenestration), balcony or roof of a high rise building, cliff, dam or bridge.

This method, in most cases, results in severe consequences if the attempt fails, such as paralysis, organ damage, and bone fractures.

In the United States, jumping is among the least common methods of suicide (less than 2% of all reported suicides in the United States for 2005).[21]

In Hong Kong, jumping is the most common method of suicide, accounting for 52.1% of all reported suicide cases in 2006 and similar rates for the years prior to that.[85] The Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention of the University of Hong Kong believes that it may be due to the abundance of easily accessible high rise buildings in Hong Kong.[86]

There have been several documented cases of suicide by skydiving, by people who deliberately failed to open their parachute (or removed it during freefall) and were found to have left suicide notes.[87][88] Expert Skydiver and former 22 SAS Soldier Charles (Nish) Bruce QGM completed suicide[89] following eight years of mental illness and periods under section by leaping from a Cessna 172 from 5000 feet over Fyfield, Oxfordshire without a parachute whilst on a private flight home from Spain to Hinton Skydiving Centre.[90] His military history and the manner of his death resulted in extensive media coverage.[91][92][93] Numerous sources[94][95] have looked to attribute his breakdown and suicide to posttraumatic stress disorder.[96]

Poison

Suicide can be completed by using fast-acting poisons, such as hydrogen cyanide, or substances which are known for their high levels of toxicity to humans.[97] For example, most of the people of Jonestown died when Jim Jones, the leader of a religious sect, organized a mass suicide by drinking a cocktail of diazepam and cyanide in 1978 ("Drinking the Kool-Aid").[98] Sufficient doses of some plants like the belladonna family, castor beans, Jatropha curcas and others, are also toxic. Poisoning through the means of toxic plants is usually slower and is relatively painful.[99]

Pesticide

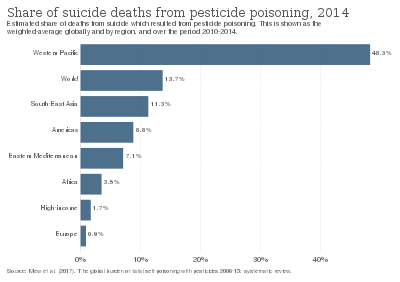

Worldwide, 30% of suicides are from pesticide poisonings. The use of this method, however, varies markedly in different areas of the world, from 4% in Europe to more than 50% in the Pacific region.[101] In the US, pesticide poisoning is used in about 12 suicides per year.[102]

Poisoning by farm chemicals is very common among women in the Chinese countryside, and is regarded as a major social problem in the country.[103] In Finland, the highly lethal pesticide Parathion was commonly used for suicide in the 1950s. When access to the chemical was restricted, other methods replaced it, leading researchers to conclude that restricting certain suicide methods does little to impact the overall suicide rate.[104] However, in Sri Lanka, both suicide by pesticide and total suicides declined after first class 1 and later endosulfan were banned.[105]

Drug overdose

Overdose is a method of suicide which involves taking medication in doses greater than the indicated levels, or in a combination that will interact either to cause harmful effects or increase the potency of one or other of the substances. In the United States drug overdoses represents about 60% of suicide attempts and 14% of deaths.[22] The risk of death in overdose is about 2%.[22]

An overdose is often the expressed preferred method of dignified dying among members of right-to-die societies. A poll among members of right-to-die society Exit International suggested that 89% would prefer to take a pill, rather than use a plastic exit bag, a CO generator, or use "slow euthanasia".[106] Death by helium inhalation however is the more common method preferred in practice, largely owing to its reliability.[107]

In the United States most deaths due to drug overdose are related to opioids.[108] While barbiturates have long been used for suicide, they are increasingly difficult to acquire. Dutch right-to-die society WOZZ proposed several safe alternatives to barbiturates for use in euthanasia.[109]

Analgesic overdose attempts are among the most common, due to easy availability of over-the-counter substances.[110] Overdose may also take place when mixing medications in a cocktail with one another, or with alcohol or illegal drugs. This method may leave confusion over whether the death was a suicide or accidental, especially when alcohol or other judgment-impairing substances are also involved and no suicide note was left behind.

Carbon monoxide

A particular type of poisoning involves inhalation of high levels of carbon monoxide. Death usually occurs through hypoxia. In most cases carbon monoxide (CO) is used because it is easily available as a product of incomplete combustion. A failed attempt can result in memory loss and other symptoms.[111][112][113]

Carbon monoxide is a colorless and odorless gas, so its presence cannot be detected by sight or smell. It acts by binding preferentially to the hemoglobin in the person's blood, displacing oxygen molecules and progressively deoxygenating the blood, eventually resulting in the failure of cellular respiration, and death. Carbon monoxide is extremely dangerous to bystanders and people who may discover the body, so "Right to Die" advocates like Philip Nitschke recommend the use of safer alternatives like nitrogen, for example in his EXIT euthanasia device.

In the past, before air quality regulations and catalytic converters, suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning would often be achieved by running a car's engine in a closed space such as a garage, or by redirecting a running car's exhaust back inside the cabin with a hose. Motor car exhaust may have contained up to 25% carbon monoxide. However, catalytic converters found on all modern automobiles eliminate over 99% of carbon monoxide produced.[114] As a further complication, the amount of unburned gasoline in emissions can make exhaust unbearable to breathe well before losing consciousness.

The incidence of suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning through burning charcoal, such as a barbecue in a sealed room, appears to have risen. This has been referred to by some as "death by hibachi".[115] As with other suicide methods, charcoal burning suicide attempters can live from the attempt, which typically leaves a person with severe brain damage due to cerebral anoxia.

Other toxins

Detergent-related suicide involves mixing household chemicals to produce hydrogen sulfide or other poisonous gases.[116][117][118][119] The suicide rates by domestic gas fell from 1960 to 1980.[120]

At the end of the 19th century in Britain there were more suicides from carbolic acid than from any other poison because there was no restriction on its sale. Braxton Hicks and other coroners called for its sale to be prohibited.[121][122]

Several creatures, such as spiders, snakes, and scorpions, carry venoms that can easily and quickly kill a person. These substances can be used to conduct suicide. For example, Cleopatra supposedly had an asp bite her when she heard of Marc Antony's death.[123]

Ritual suicide

Ritual suicide is performed in a prescribed way, often as part of a religious or cultural practice.

Sokushinbutsu

Sokushinbutsu is death and entering mummification while alive in Buddhism.[124]

Sati

Sati is self-immolation in Hinduism.[125][126][127]

Prayopavesa

Prayopavesa is a practice in Hinduism that denotes the suicide by fasting of a person, who has no desire or ambition left, and no responsibilities remaining in life. It is also allowed in cases of terminal disease or great disability.[128][129][130]

Sallekhana

Sallekhana is the religious practice of voluntarily fasting to death by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids. It is viewed in Jainism as the thinning of human passions and the body, and another means of destroying rebirth-influencing karma by withdrawing all physical and mental activities. It is not considered as a suicide by Jain scholars because it is not an act of passion, nor does it deploy poisons or weapons. After the sallekhana vow, the ritual preparation and practice can extend into years.[133][134]

Seppuku

Seppuku ("cut-belly", used in writing) or hara-kiri ("belly slitting", used when talking) is a Japanese ritual method of suicide, practiced mostly in the medieval era, though some isolated cases appear in modern times. For example, Yukio Mishima died by seppuku in 1970 after a failed coup d'état intended to restore full power to the Japanese emperor.[135] Unlike other methods of suicide, this was regarded as a way of preserving one's honor. The ritual is part of bushido, the code of the samurai.

As originally performed solely by an individual, it was an extremely painful method by which to die. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special cloth, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. The samurai would open his kimono, take up his wakizashi (short sword), fan, or a tantō and plunge it into his abdomen, making first a left-to-right cut and then a second slightly upward stroke. As the custom evolved, a selected attendant (kaishakunin, his second) stood by, and on the second stroke would perform daki-kubi, where the warrior is all but decapitated leaving only a slight band of flesh attaching the head to the body, so as to not let the head fall off and roll on the ground, which was considered dishonorable in feudal Japan. The act eventually became so highly ritualistic that the samurai would only have to reach for his sword, and his kaishakunin would execute the killing stroke.

Autosacrifice

Human sacrifice was a religious activity throughout Mesoamerica. In Aztec and Maya culture, autosacrifice involving self-decapitation by priests and kings is depicted in artworks.[136][137] The sacrifice is usually depicted holding an obsidian knife or axe to the side of the neck.[137][138]

Some forms of Durga worship in Indian Hinduism involve a male devotee offering himself as a sacrifice through ritual self-decapitation with a curved sword. This is designed to obtain a favor from the deity for a third party.[139][140]

Self-strangulation

This method involves tightening a ligature around the neck so as to compress the carotid arteries, preventing the supply of oxygen to the brain and resulting in unconsciousness and death. The technique is also associated with certain types of judo holds and restraints, and auto-erotic asphyxiation. This also may be done with twist ties.[141]

Starvation

A hunger strike may ultimately lead to death. Starvation has been used by Hindu and Jain ascetics as a ritual method of penance (known as Prayopavesa and Santhara respectively) or as a method of speeding up one's own death,[142] and Albigensians or Cathars also fasted after receiving the 'consolamentum' sacrament, in order to die while in a morally perfect state.[143] This method of death is often associated with political protest, such as the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike by Irish republican paramilitary prisoners demanding prisoner of war status, of whom ten died. The explorer Thor Heyerdahl refused to eat or take medication for the last month of his life, after he was diagnosed with cancer.[144]

An anorexia nervosa death caused by self-starvation is not listed on death certificates as suicide. In the UK, refusal to adhere to norms regarding food and drink consumption can lead to being detained, treated and even force fed under section 3 of the Mental Health Act 1983. The effects of this can be substantial and may result in 'sectioning/involuntary commitment, with some cases demonstrating a level of persistence from mental health professionals in the resistance of such methods.[145] Force feeding has been described as "extremely unpleasant" and "undignified", with sociologist June Purvis comparing it to sexual assault.[146]

Suffocation

Suicide by suffocation is the act of inhibiting one's ability to breathe or limiting oxygen uptake while breathing, causing hypoxia and eventually asphyxia. This may involve an exit bag (a plastic bag fixed over the head) or confinement in an enclosed space without oxygen. These attempts involve using depressants to make the user pass out due to the oxygen deprivation before the instinctive panic and the urge to escape due to the hypercapnic alarm response.

It is impossible for someone to die by simply holding their breath, as the level of oxygen in the blood becomes too low, the brain sends an involuntary reflex, and the person breathes in as the respiratory muscles contract. Even if one is able to overcome this response to the point of becoming unconscious, in this condition, it is no longer possible to control breathing, and a normal rhythm is reestablished.[147]

Because of this, one is more likely to die by suicide through gas inhalation than attempting to prevent breathing all together. Inert gases such as helium, nitrogen, and argon, or toxic gases such as carbon monoxide are commonly used in suicides by suffocation due to their ability to quickly render a person unconscious, and may cause death within minutes.[148][149]

Suicide attack

A suicide attack is an attack in which the attacker (attacker being either an individual or a group) intends to kill others and intends to die in the process of doing so (e.g. Columbine, Virginia Tech and 9/11). In a suicide attack in the strictest sense, the attacker dies by the attack itself, for example in an explosion or crash caused by the attacker. The term is sometimes loosely applied to an incident in which the intention of the attacker is not clear, though he is almost sure to die by the defense or retaliation of the attacked party, e.g., "suicide by cop", that is, menacing or assaulting an armed police officer with a weapon or apparent or proclaimed harmful intent which all but ensures that the officer will use deadly force to terminate the attack. This can also be referred to as murder-suicide.

Such attacks are typically motivated by religious or political ideologies, and have been carried out using numerous methods. For example, attackers might attach explosives directly to their bodies before detonating themselves close to their target, also known as suicide bombing. They may use a car bomb or other machinery to cause maximum damage (e.g. Japanese kamikaze pilots during World War II).

Vehicular impact

Another way of completing suicide is deliberately placing oneself in the path of a large and fast-moving vehicle, resulting in fatal impact.

Rail

_7.12.2008.jpg)

Suicide is accomplished by positioning oneself on a railway track when a train approaches or in advance, or driving a car onto the tracks.[150] Failed attempts may result in profound injuries, such as multiple fractures, amputations, concussion and severe mental and physical handicapping.[151]

Unlike on underground railways, in suicides involving above-ground railway lines, the person will often simply stand or lie on the tracks, waiting for the arrival of the train. As the trains usually travel at high speeds (usually between 80 and 200 km/h), the driver is usually unable to bring the train to a halt before the collision. This type of suicide may be traumatizing to the driver of the train and may lead to post-traumatic stress disorder.[152]

Europe

In the Netherlands, as many as 10% of all suicides are rail-related.[153] In Germany, 7% of all suicides occur in this manner.[154] To deal with an average of three suicide incidents per day, Deutsche Bahn is cooperating with a hospital in Malente to offer specific treatment to traumatized train drivers.[155][156][157] In recent years, some German train drivers succeeded in getting compensation payments from parents or spouses.[158] In Sweden, less densely populated and with a smaller proportion of the population living in proximity of railroad tracks, 5% of all suicides are rail-related. In Belgium, nearly 6% of suicides are rail related with a disproportionate amount occurring in the Dutch-speaking region (10% rate in Flanders). The rate of direct death is one in two. The location of many suicides occur at or very close to stations, which is also uncharacteristic of suicides in other European countries. The disruption to the rail system can be substantial.[159] In Belgium where rail service is frequently interrupted due to a high level of suicide by rail, families are expected to cover the substantial cost of rail network standstill.[160]

Japan

Trains on Japanese railroads cause a large number of suicides every year. Suicide by train is seen as something of a social problem, especially in the larger cities such as Tokyo or Nagoya, because it disrupts train schedules and if one occurs during the morning rush-hour, causes numerous commuters to arrive late for work. However, suicide by train persists despite a common policy among life insurance companies to deny payment to the beneficiary in the event of suicide by train (payment is usually made in the event of most other forms of suicide). Suicides involving the high-speed bullet-train, or Shinkansen are extremely rare, as the tracks are usually inaccessible to the public (i.e. elevated and/or protected by tall fences with barbed wire) and legislation mandates additional fines against the family and next-of-kin of the person who died by suicide.[161] As in Belgium, family members of the person who died by suicide may be expected to cover the cost of rail disruption, which can be significantly extensive. It has been argued this prevents possible suicide, as the person who is considering suicide would want to spare the family not only the trauma of a lost family member but also being sued in court; however there is insufficient evidence to support this assertion.[162]

North America

According to the Federal Railroad Administration, in the U.S., there are 300 to 500 train suicides a year.[163] A study of completed suicides on railway rights-of-ways by the Federal Railroad Administration found that the decedents tended to live near railroad tracks, were less likely to have access to firearms, and were significantly compromised by both severe mental disorder and substance abuse.[164]

Reducing the number of rail-related suicides

Methods to reduce the number of rail-related suicides include CCTV surveillance of stretches where suicides frequently occur, often with direct links to the local police or surveillance companies. This enables the police or guards to be on the scene within minutes after the trespassing was noted. Public access to the tracks is also made more difficult by erecting fences. Trees and bushes are cut down around the tracks in order to increase driver visibility.

In southern Sweden, where a suicide hotspot is located south of the university town Lund, CCTV cameras with direct links to the local police have been installed. Similar packages will be installed on other hotspots throughout the nation.

In the Netherlands, where several suicide hotspots are located by rail tracks next to mental wards, loud speakers and strong lights that activate when trespassing is noted, have been installed next to these hotspots.

Metro system

Jumping in front of an oncoming subway train has a 59% death rate, lower than the 90% death rate for rail-related suicides. This is most likely because trains traveling on open tracks travel relatively quickly, whereas trains arriving at a subway station are decelerating so that they can stop and board passengers.

Different methods have been used in order to decrease the number of suicide attempts in the underground: for instance, deep drainage pits halve the likelihood of fatality. Separation of the passengers from the track by means of platform screen doors is being introduced in some stations, but is expensive.[165]

Car

Some suicides are the result of intended car crashes. This especially applies to single-occupant, single-vehicle accidents, "because of the frequency of its use, the generally accepted inherent hazards of driving, and the fact that it offers the individual an opportunity to imperil or end his life without consciously confronting himself with his suicidal intent."[166] There is always the risk that a car accident will affect other road users; for example, a car that brakes abruptly or swerves to avoid a suicidal pedestrian may collide with something else on the road, and the driver could be harmed.

The real percentage of suicides among car accidents is not reliably known; studies by suicide researchers tell that "vehicular fatalities that are suicides vary from 1.6% to 5%".[167] Some suicides are misclassified as accidents, because suicide must be proven; "It is noteworthy that even when suicide is strongly suspected but a suicide note is not found, the case will be classified an 'accident.'"[168]

Some researchers believe that suicides disguised as traffic accidents are far more prevalent than previously thought. One large-scale community survey in Australia among suicidal people provided the following numbers: "Of those who reported planning a suicide, 14.8% (19.1% of male planners and 11.8% of female planners) had conceived to have a motor vehicle "accident"... Of all attempters, 8.3% (13.3% of male attempters) had previously attempted via motor vehicle collision."[169]

Aircraft

Between 1983 and 2003, 36 pilots died by suicide by aircraft in the United States.[170] There have been well documented suicide attacks by aircraft, including Japanese Kamikaze attacks, and the September 11 attacks. On 24 March 2015, a Germanwings co-pilot deliberately crashed Germanwings Flight 9525 into the French Alps to complete suicide, killing 150 people with him.[171][172]

Suicide by pilot has also been proposed as a potential cause for the disappearance and following destruction of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 in 2014,[173] with supporting evidence being found in a flight simulator application used by the flight's pilot.[174]

In media

A number of books have been written as aids in suicide, including Final Exit and The Peaceful Pill Handbook, the latter of which overlaps with euthanasia methods. Some books on this topic have been banned by governments.

There are also suicide sites. These sites include suicide bridges such as the Golden Gate Bridge (which has had 1558 accounted deaths as of 2012, with only 33 having survived).[175]

See also

- Advocacy of suicide

- List of suicides from antiquity to the present

- List of suicides in the 21st century

- Suicide legislation

- Suicide prevention

References

- "Preventing Suicide |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC". www.cdc.gov. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "Suicide". www.who.int. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Yip, Paul S. F.; Caine, Eric; Yousuf, Saman; Chang, Shu-Sen; Wu, Kevin Chien-Chang; Chen, Ying-Yeh (23 June 2012). "Means restriction for suicide prevention". Lancet (London, England). 379 (9834): 2393–2399. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 6191653. PMID 22726520.

- Turecki, Gustavo; Brent, David A. (19 March 2016). "Suicide and suicidal behaviour". Lancet (London, England). 387 (10024): 1227–1239. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 5319859. PMID 26385066.

- Berk, Michele (12 March 2019). Evidence-Based Treatment Approaches for Suicidal Adolescents: Translating Science Into Practice. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-61537-163-1.

- Pounder, Derrick. "Lecture Notes in Forensic Medicine" (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Baker, Susan P.; O'Neill, Brian; Ginsburg, Marvin J.; Li, Guohua (1991). The Injury Fact Book. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-974870-9.

- Dutton, Richard P. (March 2001). "Pathophysiology of traumatic shock". Seminars in Anesthesia, Perioperative Medicine and Pain. 20 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1053/sane.2001.21091.

- Bukhari, AJ; Saleem, M; Bhutta, AR; Khan, AZ; Abid, KJ (October 2004). "Spaghetti wrist: management and outcome". Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 14 (10): 608–11. doi:10.2004/JCPSP.608611 (inactive 21 May 2020). PMID 15456551.

- Baumrucker, Steven (5 September 2016). "Science, hospice, and terminal dehydration". American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 16 (3): 502–3. doi:10.1177/104990919901600302. PMID 10661057.

- Lieberson, Alan D. "Treatment of Pain and Suffering in the Terminally Ill".

- Bernat, James L. (27 December 1993). "Patient Refusal of Hydration and Nutrition". Archives of Internal Medicine. 153 (24): 2723–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.1993.00410240021003. PMID 8257247.

- Miller, Franklin G.; Meier, Diane E. (2004). "Voluntary Death: A Comparison of Terminal Dehydration and Physician-Assisted Suicide". Annals of Internal Medicine. 128 (7): 559–62. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00007. PMID 9518401.

- Jacobs, Sandra (24 July 2003). "Death by Voluntary Dehydration — What the Caregivers Say". New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (4): 325–326. doi:10.1056/NEJMp038115. PMID 12878738.

- Arehart-Treichel, Joan (16 January 2004). "Terminally Ill Choose Fasting Over M.D.-Assisted Suicide". Psychiatric News. 39 (2): 15–51. doi:10.1176/pn.39.2.0015.

- Smith, Wesley J. (12 November 2003). "A 'Painless' Death?". The Weekly Standard.

- Orentlicher, David (23 October 1997). "The Supreme Court and Physician-Assisted Suicide — Rejecting Assisted Suicide but Embracing Euthanasia". New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (17): 1236–1239. doi:10.1056/NEJM199710233371713. PMID 9340517.

- Frances, Richard J.; Wikstrom, Thomas; Alcena, Valiere (1985). "Contracting AIDS as a means of committing suicide". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (5): 656. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.5.656b. PMID 3985206.

- Flavin, Daniel K.; Franklin, John E.; Frances, Richard J. (1986). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and suicidal behavior in alcohol-dependent homosexual men". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 143 (11): 1440–1442. doi:10.1176/ajp.143.11.1440. PMID 3777237.

- Ronald W. Maris; Alan L. Berman; Morton M. Silverman; Bruce M. Bongar (2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. Guilford Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- "WISQARS Leading Causes of Death Reports". Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- Conner, Andrew; Azrael, Deborah; Miller, Matthew (3 December 2019). "Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014". Annals of Internal Medicine. 171 (12): 885–895. doi:10.7326/M19-1324. PMID 31791066.

- Liptak, Adam (9 February 2008). "Electrocution Is Banned in Last State to Rely on It". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- Fish, RM; Geddes, LA (12 October 2009). "Conduction of electrical current to and through the human body: a review". ePlasty. 9: e44. PMC 2763825. PMID 19907637.

- "SATI". Sos-sexisme.org. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- Diana Kendall (2011). Sociology in Our Times: The Essentials. Cengage Learning. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-111-30550-5.

- Cedric A. Mims (1998). When we die. Robinson. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-85487-529-7.

- Edward Robb Ellis; George N. Allen (1961). Traitor within: our suicide problem. Doubleday. p. 98.

- "Jumpers". The New Yorker. 13 October 2003.

- "Suicide rate by firearm". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Grinshteyn, Erin; Hemenway, David (March 2016). "Violent Death Rates: The US Compared with Other High-income OECD Countries, 2010". The American Journal of Medicine. 129 (3): 266–273. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025. PMID 26551975.

- "NIMH » Suicide". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "A review of suicide statistics in Australia". Government of Australia.

- McIntosh, JL; Drapeau, CW (28 November 2012). "U.S.A. Suicide: 2010 Official Final Data" (PDF). suicidology.org. American Association of Suicidology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Backous, Douglas (5 August 1993). "Temporal Bone Gunshot Wounds: Evaluation and Management". Baylor College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- Miller, M; Azrael, D; Barber, C (April 2012). "Suicide mortality in the United States: the importance of attending to method in understanding population-level disparities in the burden of suicide". Annual Review of Public Health. 33: 393–408. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124636. PMID 22224886.

- Council on Injury, Violence (1 November 2012). "Firearm-Related Injuries Affecting the Pediatric Population". Pediatrics. 130 (5): e1416–e1423. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2481. PMID 23080412.

- Westefeld, John S.; Gann, Lianne C.; Lustgarten, Samuel D.; Yeates, Kevin J. (2016). "Relationships between firearm availability and suicide: The role of psychology". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 47 (4): 271–277. doi:10.1037/pro0000089.

- Anglemyer, Andrew; Horvath, Tara; Rutherford, George (21 January 2014). "The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization Among Household Members". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (2): 101–110. doi:10.7326/M13-1301. PMID 24592495.

- Brent, David A. (April 2001). "Firearms and Suicide". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 932 (1): 225–240. Bibcode:2001NYASA.932..225B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05808.x. PMID 11411188.

- Miller, M.; Swanson, S. A.; Azrael, D. (13 January 2016). "Are We Missing Something Pertinent? A Bias Analysis of Unmeasured Confounding in the Firearm-Suicide Literature". Epidemiologic Reviews. 38 (1): 62–9. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxv011. PMID 26769723.

- "Guns and suicide: A fatal link". Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 15 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Studdert, David M.; Zhang, Yifan; Swanson, Sonja A.; Prince, Lea; Rodden, Jonathan A.; Holsinger, Erin; Spittal, Matthew; Wintemute, Garen; Miller, Matthew (2020). "Handgun Ownership and Suicide in California". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382: 2220–2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1916744.

- Lewiecki, E. Michael; Miller, Sara A. (January 2013). "Suicide, Guns, and Public Policy". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (1): 27–31. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300964. PMC 3518361. PMID 23153127.

- Committee on Law and Justice (2004). "Executive Summary". Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review. National Academy of Science. doi:10.17226/10881. ISBN 978-0-309-09124-4.

- Kellermann, A.L.; Rivara, F.P.; Somes, G.; Francisco, Jerry; et al. (1992). "Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership". New England Journal of Medicine. 327 (7): 467–472. doi:10.1056/NEJM199208133270705. PMID 1308093.

- Miller, Matthew; Hemenway, David (2001). Firearm Prevalence and the Risk of Suicide: A Review. Harvard Health Policy Review. p. 2.

One study found a statistically significant relationship between estimated gun ownership levels and suicide rate across 14 developed nations (e.g. where survey data on gun ownership levels were available), but the association lost its statistical significance when additional countries were included.

- Birckmayer, Johanna; Hemenway, David (September 2001). "Suicide and Firearm Prevalence: Are Youth Disproportionately Affected?". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 31 (3): 303–310. doi:10.1521/suli.31.3.303.24243. PMID 11577914.

- Miller, Matthew; Hemenway, David (March 1999). "The relationship between firearms and suicide". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 4 (1): 59–75. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00057-8.

- Brent, D. A.; Bridge, J. (1 May 2003). "Firearms Availability and Suicide: Evidence, Interventions, and Future Directions". American Behavioral Scientist. 46 (9): 1192–1210. doi:10.1177/0002764202250662.

- Briggs, Justin Thomas; Tabarrok, Alexander (March 2014). "Firearms and suicides in US states". International Review of Law and Economics. 37: 180–188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.3579. doi:10.1016/j.irle.2013.10.004.

- Miller, Matthew; Warren, Molly; Hemenway, David; Azrael, Deborah (April 2015). "Firearms and suicide in US cities". Injury Prevention. 21 (e1): e116–e119. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040969. PMID 24302479.

- Miller, M.; Barber, C.; White, R. A.; Azrael, D. (23 August 2013). "Firearms and Suicide in the United States: Is Risk Independent of Underlying Suicidal Behavior?". American Journal of Epidemiology. 178 (6): 946–955. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt197. PMID 23975641.

- Miller, M (1 June 2006). "The association between changes in household firearm ownership and rates of suicide in the United States, 1981-2002". Injury Prevention. 12 (3): 178–182. doi:10.1136/ip.2005.010850. PMC 2563517. PMID 16751449.

- Miller, Matthew; Lippmann, Steven J.; Azrael, Deborah; Hemenway, David (April 2007). "Household Firearm Ownership and Rates of Suicide Across the 50 United States". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 62 (4): 1029–1035. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000198214.24056.40. PMID 17426563.

- Anestis, MD; Houtsma, C (13 March 2017). "The Association Between Gun Ownership and Statewide Overall Suicide Rates". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 48 (2): 204–217. doi:10.1111/sltb.12346. PMID 28294383.

- Stroebe, Wolfgang (November 2013). "Firearm possession and violent death: A critical review". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 18 (6): 709–721. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.025.

- Siegel, Michael; Rothman, Emily F. (July 2016). "Firearm Ownership and Suicide Rates Among US Men and Women, 1981–2013". American Journal of Public Health. 106 (7): 1316–1322. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303182. PMC 4984734. PMID 27196643.

- Cook, Philip J.; Ludwig, Jens (2000). "Chapter 2". Gun Violence: The Real Costs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513793-4.

- Ikeda, Robin M.; Gorwitz, Rachel; James, Stephen P.; Powell, Kenneth E.; Mercy, James A. (1997). Fatal Firearm Injuries in the United States, 1962-1994: Violence Surveillance Summary Series, No. 3. National Center for Injury and Prevention Control.

- Anglemyer, A; Horvath, T; Rutherford, G (21 January 2014). "The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (2): 101–10. doi:10.7326/M13-1301. PMID 24592495.

- Anestis, Michael D.; Khazem, Lauren R.; Law, Keyne C.; Houtsma, Claire; LeTard, Rachel; Moberg, Fallon; Martin, Rachel (October 2015). "The Association Between State Laws Regulating Handgun Ownership and Statewide Suicide Rates". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (10): 2059–2067. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302465. PMC 4566551. PMID 25880944.

- Conner, Kenneth R; Zhong, Yueying (November 2003). "State firearm laws and rates of suicide in men and women". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 25 (4): 320–324. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00212-5. PMID 14580634.

- Chapman, S; Alpers, P; Agho, K; Jones, M (1 December 2006). "Australia's 1996 gun law reforms: faster falls in firearm deaths, firearm suicides, and a decade without mass shootings". Injury Prevention. 12 (6): 365–372. doi:10.1136/ip.2006.013714. PMC 2704353. PMID 17170183.

- Caron, Jean (October 2004). "Gun Control and Suicide: Possible Impact of Canadian Legislation to Ensure Safe Storage of Firearms". Archives of Suicide Research. 8 (4): 361–374. doi:10.1080/13811110490476752. PMID 16081402.

- Caron, Jean; Julien, Marie; Huang, Jean Hua (April 2008). "Changes in Suicide Methods in Quebec between 1987 and 2000: The Possible Impact of Bill C-17 Requiring Safe Storage of Firearms". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 38 (2): 195–208. doi:10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.195. PMID 18444777.

- Cheung, AH; Dewa, CS (2005). "Current trends in youth suicide and firearms regulations". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 96 (2): 131–5. doi:10.1007/BF03403676. PMC 6975744. PMID 15850034.

- Beautrais, A. L.; Fergusson, D. M.; Horwood, L. J. (26 June 2016). "Firearms Legislation and Reductions in Firearm-Related Suicide Deaths in New Zealand". Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 40 (3): 253–259. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01782.x. PMID 16476153.

- Beautrais, Annette L.; Joyce, Peter R.; Mulder, Roger T. (26 June 2016). "Access to Firearms and the Risk of Suicide: A Case Control Study". Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 30 (6): 741–748. doi:10.3109/00048679609065040. PMID 9034462.

- "Firearms, Accidental Deaths, Suicides and Violent Crime: An Updated Review of the Literature with Special Reference to the Canadian Situation". 10 March 1999.

- Mann, JJ; Michel, CA (1 October 2016). "Prevention of Firearm Suicide in the United States: What Works and What Is Possible". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (10): 969–979. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010069. PMID 27444796.

- Cage, Feilding; Dance, Gabriel (16 January 2013). "Gun laws in the US, state by state – interactive". the Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Prasad, Ritu (11 June 2018). "Why US suicide rate is on the rise". Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Loftin, Colin; McDowall, David; Wiersema, Brian; Cottey, Talbert J. (5 December 1991). "Effects of Restrictive Licensing of Handguns on Homicide and Suicide in the District of Columbia". New England Journal of Medicine. 325 (23): 1615–1620. doi:10.1056/nejm199112053252305. PMID 1669841.

- Britt, Chester L.; Kleck, Gary; Bordua, David J. (1996). "A Reassessment of the D.C. Gun Law: Some Cautionary Notes on the Use of Interrupted Time Series Designs for Policy Impact Assessment". Law & Society Review. 30 (2): 361–380. doi:10.2307/3053963. JSTOR 3053963.

- Lee, Sing; et al. (2003), "Suicide as Resistance in Chinese Society", Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 297, ISBN 9780415301701.

- Lee, Jonathan H.X.; et al. (2011), Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife, ABC-CLIO, p. 11, ISBN 9780313350672.

- Lee, Evelyn (1997), Working with Asian Americans: A Guide for Clinicians, Guilford Press, p. 59, ISBN 9781572305700.

- Bourne, P G (August 1973). "Suicide among Chinese in San Francisco". American Journal of Public Health. 63 (8): 744–50. doi:10.2105/AJPH.63.8.744. PMC 1775294. PMID 4719540.

- Ronald W. Maris; Alan L. Berman; Morton M. Silverman; Bruce Michael Bongar (2000). Comprehensive Textbook of Suicidology. Guildford Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- Hughes, Robert (1988). The Fatal Shore, The Epic Story of Australia's Founding (first ed.). Vintage Books.

- "South African Police Say Man Killed Himself by Going Into Croc-Infested Waters". NewsCore. 27 March 2015.

- "BBC NEWS - Asia-Pacific - Thai woman eaten by crocodiles". news.bbc.co.uk. 11 August 2002.

- "Thai woman in crocodile pit suicide". BBC News. 16 September 2014 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Method Used in Completed Suicide". HKJC Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "遭家人責罵:掛住上網媾女唔讀書 成績跌出三甲 中四生跳樓亡". Apple Daily. 9 August 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- W.G. Eckert; W.S. Reals (1978). "Air disaster investigation". Legal Medicine Annual: 57–70. PMID 756947.

- David Dolinak; Evan W. Matshes; Emma O. Lew (2005). Forensic pathology: principles and practice. Academic Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-12-219951-6.

- Allison, Rebecca (20 June 2002). "Depressed pilot leapt to death". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "SAS soldier dies in plane plunge". CNN. 10 January 2002. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "Falkland veterans claim suicide toll". BBC News. 13 January 2002. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- Dyer, Clare (16 January 2002). "The forgotten army". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- https://www.theguardian.com/g2/story/0,3604,630819,00.html - Addley, Esther "The Suicide of an Ex-SAS Man, Into the Abyss", 11 January 2002, Paragraph 8 - The Guardian

- Clive Emsley, Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief: Crime and the British Armed Services since 1914 (2013). Page 193. ISBN 978-0-19-965371-3.

- Michael Kennedy, Soldier 'I' - The Story of an SAS Hero (2011). Page 350. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781849086509

- Tony Banks, Storming the Falklands, My War and After (2012). Chapter 6. Little Brown Publishing. ISBN 9780748130603

- "Poisoning drugs". Forums.yellowworld.org. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Ministry of Terror - The Jonestown Cult Massacre, Elissayelle Haney, Infoplease, 2006.

- "Poisoning methods". Ctrl-c.liu.se. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "Share of suicide deaths from pesticide poisoning". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, Konradsen F (2007). "The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: Systematic review". BMC Public Health. 7: 357. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-357. PMC 2262093. PMID 18154668.

- "Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2018 Request". wonder.cdc.gov. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Griffiths, Daniel (4 June 2007). "Rural China's suicide problem". BBC News. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- A Ohberg; J Lonnqvist; S Sarna; E Vuori; A Penttila (1995). "Trends and availability of suicide methods in Finland. Proposals for restrictive measures". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1192/bjp.166.1.35. PMID 7894873.

- Hvistendahl, M. (2013). "In Rural Asia, Locking Up Poisons to Prevent Suicides". Science. 341 (6147): 738–9. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..738H. doi:10.1126/science.341.6147.738. PMID 23950528.

- Philip Nitschke. The Peaceful Pill Handbook. Exit International US, 2007. ISBN 0-9788788-2-5, p 33

- Howard M, Hall M, Jeffrey D et al., "Suicide by Asphyxiation due to Helium Inhalation, Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2010; accessed 12 May 2014

- "Drug Overdose Deaths | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Guide to a Humane Self-Chosen Death by Dr. Pieter Admiraal et al. WOZZ Foundation www.wozz.nl, Delft, The Netherlands. ISBN 90-78581-01-8.

- Brock, Anita; Sini Dominy; Clare Griffiths (6 November 2003). "Trends in suicide by method in England and Wales, 1979 to 2001". Health Statistics Quarterly. 20: 7–18. ISSN 1465-1645. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- Docker, C (2013). Five Last Acts - The Exit Path. p. 368.

- Hay, Phillipa J; Denson, Linley A; van Hoof, Miranda; Blumenfeld, Natalia (August 2002). "The neuropsychiatry of carbon monoxide poisoning in attempted suicide". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 53 (2): 699–708. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00424-5. PMID 12169344.

- Carbon monoxide poisoning: Four kinds of survivors "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 12 May 2014

- Vossberg B, Skolnick J (1999). "The role of catalytic converters in automobile carbon monoxide poisoning: a case report". Chest. 115 (2): 580–1. doi:10.1378/chest.115.2.580. PMID 10027464.

- Howe, A. (2003). "Media influence on suicide". BMJ. 326 (7387): 498. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7387.498. PMC 1125377. PMID 12609951.

- "Japanese girl commits suicide with detergent". Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.

- CSCS.txstate.edu

- "Home". tena911.

- "DCFA.org" (PDF).

- Lester, D. (March 1990). "Changes in the methods used for suicide in 16 countries from 1960 to 1980". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 81 (3): 260–261. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06492.x. PMID 2343750.

- "Mr. A. Braxton Hicks held an inquiry at Battersea". Times [London, England]. The Times Digital Archive. 25 September 1894. p. 10.

- "Suicides By Poison". The British Medical Journal. 1 (1693): 1238. 1893. JSTOR 20224772.

- See:

- Strabo, Geographica, Book 17, Chapter 1, paragraph 10: Octavian "forced Antony to put himself to death and Cleopatra to come into his power alive; but a little later she too put herself to death secretly, while in prison, by the bite of an asp or (for two accounts are given) by applying a poisonous ointment" …

- Sextus Propertius, Elegies, Book 3, number 11: … "I saw your [Cleopatra's] arms bitten by the sacred asps, and your limbs draw sleep in by a secret path." … Available on-line at: Poetry in Translation

- Horace, Odes, Book 1, Ode 37: … "And she [Cleopatra] dared to gaze at her fallen kingdom / with a calm face, and touch the poisonous asps / with courage, so that she might drink down / their dark venom, to the depths of her heart," … Available on-line at: Poetry in Translation

- Virgil, Aeneid, Book 8, lines 696-697: … "The queen in the centre signals to her columns with the native sistrum, not yet turning to look at the twin snakes at her back." … Available on-line at: Poetry in Translation

- Jeremiah, Ken. Living Buddhas: The Self-mummified Monks of Yamagata, Japan. McFarland, 2010

- Feminist Spaces: Gender and Geography in a Global Context, Routledge, Ann M. Oberhauser, Jennifer L. Fluri, Risa Whitson, Sharlene Mollett

- Sophie Gilmartin (1997), The Sati, the Bride, and the Widow: Sacrificial Woman in the Nineteenth Century, Victorian Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 25, No. 1, p. 141, Quote: "Suttee, or sati, is the obsolete Hindu practice in which a widow burns herself upon her husband's funeral pyre..."

- On attested Rajput practice of sati during wars, see, for example Leslie, Julia (1993). "Suttee or Sati: Victim or Victor?". In Arnold, David; Robb, Peter (eds.). Institutions and Ideologies: A SOAS South Asia Reader. 10. London: Routledge. p. 46. ISBN 978-0700702848.

- "Hinduism - Euthanasia and Suicide". BBC. 25 August 2009.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (2008) [1899]. Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Universität zu Köln. p. 708. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

abstaining from food and awaiting in a sitting posture the approach of death

- "Prayopavesa". Orientalia.

- "Book excerptise: The Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom: An Anthology of Poems from Classical Tamil, the Purananuru by George L. (tr.) Hart and Hank Heifetz (tr.)". Department of Computer Science and Engineering, IIT Kanpur. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

Kapilar for King Pari #107 — When Vel Pari is killed in battle, kapilar is supposed to have committed suicide by vadakirrutal - facing North and starving.

- "From the annals of history". The Hindu. 25 June 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Sundara, A. "Nishidhi Stones and the ritual of Sallekhana" (PDF). International School for Jain Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- Dundas-Grant, J. (26 January 1929). "ASTHMA". BMJ. 1 (3551): 179. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3551.179. ISSN 0959-8138.

- Nathan, John. Mishima: A biography, Little Brown and Company: Boston/Toronto, 1974.

- Cecelia Klein. "The Ideology of Autosacrifice at the Templo Mayor" in E. H. Boone, ed. The Aztec Templo Mayor pp. 293-370. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. 1987 ISBN 0-88402-149-1

- Jürgen Kremer; Fausto Uc Flores (1993). "The Ritual Suicide of Maya Rulers". Eighth Palenque Round Table. 10: 79–91.

- Justin Kerr. "The Transformation of Xbalanqué or The Many Faces of God A1". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies.

- Miranda Eberle Shaw (2006). Buddhist goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-691-12758-3.

- George Cœdès (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Docker, Chris (2013). "Compression". Five Last Acts - The Exit Path. ISBN 9781482594096.

- Docker C, The Art and Science of Fasting in: Smith C, Docker C, Hofsess J, Dunn B, Beyond Final Exit 1995

- Greer, John Michael (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult - John Michael Greer - Google Books. ISBN 9781567183368. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- Radford, Tim (19 April 2002). "Thor Heyerdahl dies at 87". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- Wallis, Lucy (19 April 2002). "Beth's Story: What is it like to be sectioned?". BBC News. London. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- Purvis, June (19 September 2014). "Force-feeding of hunger-striking suffragettes". Times Higher Education. London.

- Kurzban, Robert (7 February 2011). "Why Can't You Hold Your Breath Until You're Dead?". Web. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Deaths Involving the Inadvertent Connection of Air-line Respirators to Inert Gas Supplies".

- Goldstein M (December 2008). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of Emergency Nursing. 34 (6): 538–542. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2007.11.014. PMID 19022078.

- Hilkevitch, Jon (4 July 2004). "When death rides the rails". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar (26 January 2005). "Suicide by Train Is a Growing Concern". Los Angeles Times.

- Mueller, Mark (18 June 2009). "Death By Train". The Star Ledger.

- Netherlands, Statistics. "Suicide death rate up to 1,647". www.cbs.nl.

- Baumert J, Erazo N, Ladwig KH (April 2006). "Ten-year incidence and time trends of railway suicides in Germany from 1991 to 2000". European Journal of Public Health. 16 (2): 173–178. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki060. PMID 16093307.

- "Ist Ihnen egal, was die Menschen von Ihnen denken?". Bild. 4 February 2009.

- Weber, Christian (2 February 2012). "Die Opfer der Lebensmüden". sueddeutsche.de (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

Alle Lokführer werden nach einem traumatischen Ereignis erst mal freigestellt, Obmänner sollen sich vor Ort um die Betroffenen kümmern, bei anhaltenden Störungen gibt es sogar eine mit der Deutschen Bahn kooperierende spezialisierte Klinik in Bad Malente

- bsh. "Ein Pionier der Psychosomatik | shz.de". shz (in German). Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Lokführer erhält Schmerzensgeld vom Witwer einer Selbstmörderin". Der Spiegel. 8 December 2006.

"Lokführer bekommt Schmerzensgeld von Hinterbliebenen". Der Spiegel. 19 September 2011. - "Travel chaos to continue ALL day at busy London station after death on tracks". Dailystar.co.uk. 11 July 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- "Les suicides coûtent 2 millions à la SNCB qui tente de se faire rembourser auprès des familles". sudinfo.be.

- French, Howard W. (6 June 2000). "Kunitachi City Journal; Japanese Trains Try to Shed a Gruesome Appeal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- New, Ultra Super. "Blood on the tracks: Who pays for deadly railway accidents? | Yen for Living".

- Noah Bierman (9 February 2010). "Striving to prevent suicide by train". Boston.com. Boston Globe.

- Martino, Michael et al. (2013). Defining Characteristics of Intentional Fatalities on Railway Rights-of-Way in the United States, 2007–2010. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration.

- Coats, T J; Walter, D P (9 October 1999). "Effect of station design on death in the London Underground: observational study". BMJ. 319 (7215): 957. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7215.957. PMC 28249. PMID 10514158.

- Selzer, M. L.; Payne, C. E. (1992). "Automobile accidents, suicide, and unconscious motivation". American Journal of Psychiatry. 119 (3): 237–40 [239]. doi:10.1176/ajp.119.3.237. PMID 13910542.

- Schmidt, Jr., C. W.; Shaffer, J. W.; Zlotowitz, H. I.; Fisher, R. S. (1977). "Suicide by vehicular crash". American Journal of Psychiatry. 134 (2): 175–178. doi:10.1176/ajp.134.2.175. PMID 835740.

- Peck, DL; Warner, K (1995). "Accident or suicide? Single-vehicle car accidents and the intent hypothesis". Adolescence. 30 (118): 463–72. PMID 7676880.

- Murray, D.; de Leo, D. (September 2007). "Suicidal behavior by motor vehicle collision". Traffic Inj Prev. 8 (3): 244–7. doi:10.1080/15389580701329351. PMID 17710713.

- Bills, Corey B.; Grabowski, Jurek George; Li, Guohua (2005). "Suicide by Aircraft: A Comparative Analysis". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 76 (8): 715–9. PMID 16110685.

- Clark, Nicola; Bilefsky, Dan (26 March 2015). "Germanwings Co-Pilot Deliberately Crashed Airbus Jet, French Prosecutor Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 4U9525: Co-pilot put plane into descent, prosecutor says". CBC News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Wescott, Richard (16 April 2015). "Flight MH370: Could it have been suicide?". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Pells, Rachael (23 July 2016). "MH370 pilot flew 'suicide route' on a simulator 'closely matching' his final flight". The Independent. The Independent. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Hines, Kevin (12 November 2006). "He jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge . . . and lived!". BBC News. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

Further reading

- Suicide factsheet - World Health Organization

- Humphry, Derek (1997). Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. Dell. p. 240.

- Nitschke, Philip (2007). The Peaceful Pill Handbook. US: Exit International. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-9788788-2-5.

- Stone, G. (2001). Suicide and Attempted Suicide: Methods and Consequences. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-0940-3.

External links

- Hawton, K. (1 June 2000). "Doctors who kill themselves: a study of the methods used for suicide". QJM. 93 (6): 351–357. doi:10.1093/qjmed/93.6.351. PMID 10873184.

_seated%2C_holding_cup_of_hemlock_LCCN2002737399.jpg)