Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man".[2] He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders.[3] Newspapers and magazines published photographs of Lilienthal gliding, favourably influencing public and scientific opinion about the possibility of flying machines becoming practical. On 9 August 1896, his glider stalled and he was unable to regain control. Falling from about 15 m (50 ft), he broke his neck and died the next day, 10 August 1896.

Otto Lilienthal | |

|---|---|

Otto Lilienthal, c. 1896 | |

| Born | Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal 23 May 1848 |

| Died | 10 August 1896 (aged 48) |

| Cause of death | Glider crash |

| Resting place | Lankwitz Cemetery, Berlin |

| Nationality | Prussian, German |

| Education | College Mechanical Engineer Major |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Known for | Successful gliding experiments |

| Net worth | $200,000 |

| Height | 6.2 |

| Spouse(s) | Agnes Fischer ( m. 1878–1896) |

| Children | 4[1] |

| Relatives | Gustav Lilienthal, brother |

Early life

Lilienthal was born on 23 May 1848 in Anklam, Pomerania Province, German kingdom of Prussia. His parents were Gustav and Caroline, née Pohle.[4] He was baptised in St. Nicholas church.[5] Some sources identify him as Jewish.[6] Lilienthal's middle-class parents had eight children, but only three survived infancy: Otto, Gustav, and Marie.[7] The brothers worked together all their lives on technical, social, and cultural projects. Lilienthal attended grammar school and studied the flight of birds with his brother Gustav (1849–1933).[8] Fascinated by the idea of manned flight, Lilienthal and his brother made strap-on wings, but failed in their attempts to fly. He attended the regional technical school in Potsdam for two years and trained at the Schwarzkopf Company before becoming a professional design engineer. He later attended the Royal Technical Academy in Berlin.

In 1867, Lilienthal began experiments in earnest on the force of air, but interrupted the work to serve in the Franco-Prussian War. Returning to civilian life, he was a staff engineer with several engineering companies and received a patent, his first, for a mining machine. He founded his own company to make boilers and steam engines.[9]

On 6 June 1878, Lilienthal married Agnes Fischer, daughter of a deputy. Music brought them together; she was trained in piano and voice while Lilienthal played the French horn and had a good tenor voice.[10] After marriage, they took up residence in Berlin and had four children: Otto, Anna, Fritz, and Frida.[1] Lilienthal published his famous book Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation in 1889.

Experiments in flight

Lilienthal's greatest contribution was in the development of heavier-than-air flight. He made his flights from an artificial hill he built near Berlin and from natural hills, especially in the Rhinow region.

The filing of a U.S. Patent in 1894 by Lilienthal directed pilots to grip the "bar" for carrying and flying the hang glider.[11] The A-frame of Percy Pilcher and Lilienthal echoes in today's control frame for hang gliders and ultralight aircraft. Working in conjunction with his brother Gustav, Lilienthal made over 2,000 flights in gliders of his design starting in 1891 with his first glider version, the Derwitzer, until his death in a gliding crash in 1896. His total flying time was five hours.[12]

At the beginning, in 1891, Lilienthal succeeded with jumps and flights covering a distance of about 25 metres (82 ft). He could use the updraft of a 10 m/s wind against a hill to remain stationary with respect to the ground, shouting to a photographer on the ground to manoeuvre into the best position for a photo. In 1893, in the Rhinow Hills, he was able to achieve flight distances as long as 250 metres (820 ft). This record remained unbeaten for him or anyone else at the time of his death.[12]

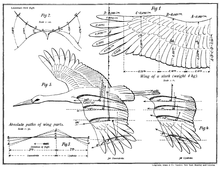

Lilienthal did research in accurately describing the flight of birds, especially storks, and used polar diagrams for describing the aerodynamics of their wings. He made many experiments in an attempt to gather reliable aeronautical data.

Projects

During his short flying career, Lilienthal developed a dozen models of monoplanes, wing flapping aircraft and two biplanes.[13] His gliders were carefully designed to distribute weight as evenly as possible to ensure a stable flight. Lilienthal controlled them by changing the center of gravity by shifting his body, much like modern hang gliders. However they were difficult to maneuvre and had a tendency to pitch down, from which it was difficult to recover. One reason for this was that he held the glider by his shoulders, rather than hanging from it like a modern hang glider. Only his legs and lower body could be moved, which limited the amount of weight shift he could achieve.

Lilienthal made many attempts to improve stability with varying degrees of success. These included making a biplane which halved the wing span for a given wing area, and by having a hinged tailplane that could move upwards to make the flare at the end of a flight easier. He speculated that flapping wings of birds might be necessary and had begun work on such a powered aircraft.

| Aircraft produced by Otto Lilienthal[14] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Date | Wing | Glider | Notes | |||

| Span (ft) |

Area (sq ft) |

Max. length (ft) |

Length (ft) |

Weight (kg) | |||

| Derwitzer Glider | 1891 | 25 (later 18) |

108 (later 84) |

6.6 | 12.8 | 18 | Wing curvature: 1/10 of length. |

| Südende Glider | 1892 | 31 | 158 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 24 | Wing curvature: 1/20 of length. |

| Maihöhe Rhinow Glider | 1893 | 22 or 23 | 150 | 8.2 | 14.3 | 20 | |

| Small Ornithopter | 1893–1896 | 22 | 129 | 8.2 | 5.5 | Weight with CO2 cylinder: 10 kg. | |

| Normal soaring apparatus | 1894 | 22 - 23 | 140-146 | 7.9 / 8.2 | 16.1 - 17.4 | 20 | At least nine gliders sold. Original gliders or fragments are preserved in museums in London, Moscow, Munich and Washington. |

| Sturmflügelmodell | 1894 | 20 | 104 | 6.6 | 14.8 | Original can be seen at the Technisches Museum Wien. | |

| Vorflügelapparat | 1895 | 29 | 204 | 9.8 | 18.4 | ||

| Small Biplane | 1895 | 19.7 / 17.1 | 104 / 105 | 7.2 / 6.9 | 15.7 | ||

| Large Biplane | 1895 | 21.6 / 20.7 | 146 / 112 | 7.5 / 7.5 | 16.1 | ||

| Big Ornithopter | 1896 | 27.9 | 188 | 8.2 | 17.4 | ||

While his lifelong pursuit was flight, Lilienthal was also an inventor and devised a small engine that worked on a system of tubular boilers.[15] His engine was much safer than the other small engines of the time. This invention gave him the financial freedom to focus on aviation. His brother Gustav (1849–1933) was living in Australia at the time, and Lilienthal did not engage in aviation experiments until his brother's return in 1885.[16]

There are 25 known Lilienthal patents.[17]

Test locations

Lilienthal performed his first gliding attempts in mid-1891 at the so-called "Windmühlenberg" near to the villages of Krielow and Derwitz which are located west of Potsdam.[18]

In 1892, Lilienthal's training area was a hill formation called "Maihöhe" in Steglitz, Berlin. He built a 4 metres (13 ft) high shed, in the shape of a tower, on top of it. This way, he obtained a "jumping off" place 10 metres (33 ft) high. The shed served also for storing his apparatus.[19]

In 1893, Lilienthal also started to perform gliding attempts in the "Rhinower Berge", at the "Hauptmannsberg" near to Rhinow and later, 1896, at the "Gollenberg" near to Stölln.[20]

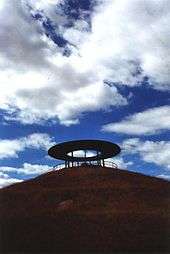

In 1894, Lilienthal built an artificial conical hill near his home in Lichterfelde, called Fliegeberg (lit. "Fly Hill").[21] It allowed him to launch his gliders into the wind no matter which direction it was coming from.[13] The hill was 15 metres (49 ft) high. There was a regular crowd of people that were interested in seeing his gliding experiments.[22]

In 1932, the Fliegeberg was redesigned by a Berlin architect Fritz Freymüller as a memorial to Lilienthal.[23] On top of the hill was built a small temple-like construction, consisting of pillars supporting a slightly sloping round roof. Inside is placed a silver globe inscribed with particulars of famous flights.[24] Lilienthal's brother Gustav and the old mechanic and assistant Paul Baylich attended the unveiling ceremony on 10 August 1932 (36 years after Otto's death).

Worldwide notice

Reports of Lilienthal's flights spread in Germany and elsewhere, with photographs appearing in scientific and popular publications.[25] Among those who photographed him were pioneers such as Ottomar Anschütz and American physicist Robert Williams Wood. He soon became known as the "father of flight" as he had successfully controlled a heavier-than-air aircraft in sustained flight.

Lilienthal was a member of the Verein zur Förderung der Luftschifffahrt, and regularly detailed his experiences in articles in its journal, the Zeitschrift für Luftschifffahrt und Physik der Atmosphäre, and in the popular weekly publication Prometheus. These were translated in the United States, France and Russia. Many people from around the world came to visit him, including Samuel Pierpont Langley from the United States, Russian Nikolai Zhukovsky, Englishman Percy Pilcher and Austrian Wilhelm Kress. Zhukovsky wrote that Lilienthal's flying machine was the most important invention in the aviation field. Lilienthal corresponded with many people, among them Octave Chanute, James Means, Alois Wolfmüller and other flight pioneers.

Final flight

On 9 August 1896, Lilienthal went, as on previous weekends, to the Rhinow Hills. The day was very sunny and not too hot (about 20 °C, or 68 °F). The first flights were successful, reaching a distance of 250 metres (820 ft) in his normal glider. During the fourth flight Lilienthal's glide pitched forward heading down quickly. Lilienthal had previously had difficulty in recovering from this position because the glider relied on weight shift which was difficult to achieve when pointed at the ground. His attempts failed and he fell from a height of about 15 metres (49 ft), while still in the glider.[26]

Paul Beylich, Lilienthal's glider mechanic, transported him by horse-drawn carriage to Stölln, where he was examined by a physician. Lilienthal had a fracture of the third cervical vertebra and soon became unconscious. Later that day he was transported in a cargo train to Lehrter train station in Berlin, and the next morning to the clinic of Ernst von Bergmann, one of the most famous and successful surgeons in Europe at the time. Lilienthal died there a few hours later (about 36 hours after the crash).

There are differing accounts of Lilienthal's last words. A popular account, inscribed on his tombstone, is "Opfer müssen gebracht werden!" ("Sacrifices must be made!"). The director of the Otto Lilienthal Museum doubts that these were his last words.[27] Otto Lilienthal was buried at Lankwitz public cemetery in Berlin.

Legacy

Lilienthal's research was well known to the Wright brothers, and they credited him as a major inspiration for their decision to pursue manned flight. However, they abandoned his aeronautical data after two seasons of gliding and began using their own wind tunnel data.[28]

Of all the men who attacked the flying problem in the 19th century, Otto Lilienthal was easily the most important. ... It is true that attempts at gliding had been made hundreds of years before him, and that in the nineteenth century, Cayley, Spencer, Wenham, Mouillard, and many others were reported to have made feeble attempts to glide, but their failures were so complete that nothing of value resulted.

— Wilbur Wright[29]

Berlin's busiest airport, Berlin Tegel "Otto Lilienthal" Airport, is named after him.

In September 1909, Orville Wright was in Germany making demonstration flights at Tempelhof aerodrome. He paid a call to Lilienthal's widow and, on behalf of himself and Wilbur, paid tribute to Lilienthal for his influence on aviation and on their own initial experiments in 1899.

In 1972, Lilienthal was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame.[30]

In 2013, American aviation magazine Flying ranked Lilienthal No. 19 on their list of the "51 Heroes of Aviation".[31]

In popular culture

- In the music video for "Losing My Religion" by R.E.M., workers build an ornithopter named "Otto" in honor of Lilienthal.[32]

- Lilienthal plays a major part (in absentia) in Theodora Goss's short story "The Wings of Meister Wilhelm," nominated for a World Fantasy Award and published in her anthology In the Forest of Forgetting.

- A fictional characterization of Lilienthal was resurrected as an evil clone in the Japanese Read or Die (2001) novels, anime, and manga.

- A Lilienthal glider serves as a major plot element in Paul Gazis's Webserial "The Airship Flying Cloud, R-505".[33]

- "Lilienthals Traum" ("Lilienthal's Dream") is a song by Reinhard Mey that charts Lilienthal's flights and death.[34]

Gallery

Lilienthal was regularly joined by photographers at his request. Most of them are well known, like Ottomar Anschütz. Lilienthal was also constantly taking his own photographs of his flying machines after 1891.[35] There are at least 145 known photographs documenting his test flights, some of excellent quality. All of them are available online at the Otto Lilienthal Museum website. The only negatives, preserved in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, were destroyed during World War II.[25]

Flight attempt of Lilienthal on the Derwitzer Glider,

Flight attempt of Lilienthal on the Derwitzer Glider,

Derwitz, 1891 Lilienthal preparing for a Small Ornithopter flight,

Lilienthal preparing for a Small Ornithopter flight,

16 August 1894- Vorflügelapparat,

29 May 1895  Normal soaring apparatus with the enlarged tail,

Normal soaring apparatus with the enlarged tail,

29 June 1895

See also

- Lilienthal Gliding Medal

- Otto Lilienthal Museum

- Aviation history

- Albrecht Berblinger

- Abbas Ibn Firnas

- George Cayley

- Jean-Marie Le Bris

- John Joseph Montgomery

- Percy Pilcher

- German inventors and discoverers

References

Notes

- "Otto Lilienthal." Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004. Retrieved: 7 January 2012.

- "Killed In Trying To Fly", New York Herald, August 12, 1896, retrieved 11 June 2019

- DLR baut das erste Serien-Flugzeug der Welt nach 2017. Retrieved: 3 March 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-02-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "St Nicholas' church". IKAREUM Lilienthal Flight Museum. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Singer, Isidore (1906). "LILIENTHAL, OTTO". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

"Lindbergh Pays Tribute to the Jewish Avlation Pioneer, Otto Lilienthal". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. August 28, 1928. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

Chessin, Judy (July 3, 2003). "The man who inspired the Wright brothers". Cleveland Jewish News. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

Bush, Lawrence (August 8, 2013). "August 9: The Jewish Wright Brothers". Jewish Currents. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

Freeman, Tzvi. "Hang Gliding". Chabad.org. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

Skaldman, Rami. "The Wright Brother's First Flight". Israel Philatelic Federation. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Anderson 2001, p. 156.

- Encyclopedia of Transportation. New York: Rand-McNally, 1977.

- "Archived copy". Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- Anderson 2001, p. 157.

- "Flying-Machine Otto Lilienthal. Patents. Retrieved: 16 November 2012.

- "From Lilienthal to the Wrights." Otto Lilienthal Museum. Retrieved: 8 January 2012.

- "Pioneers of Flight: Otto Lilienthal." Discovery Channel. Retrieved: 8 January 2012.

- Nitsch: Die Flugzeuge von Otto Lilienthal. Anklam 2016. ISBN 978-3-941681-88-0

- "Documentation of the only preserved Lilienthal engine" Otto Lilienthal Museum. Retrieved: 12 February 2018.

- Runge and Lukasch: Erfinderleben. Die Brüder Otto und Gustav Lilienthal. Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3-8333-0467-5

- "Patent archives of the Museum." Otto Lilienthal Museum. Retrieved: 12 February 2018.

- Seifert and Waßermann: Otto Lilienthal. Leben und Werk. Eine Biographie. Hamburg 1992: pp. 62–65. ISBN 3-924562-02-4

- Chanute, O. "The Flying Man." Progress in Flying Machines. Retrieved: 16 November 2012.

- Seifert and Waßermann: Otto Lilienthal. Leben und Werk. Eine Biographie. Hamburg 1992: pp. 73–80. ISBN 3-924562-02-4

- "The man who jumped off hills: Otto Lilienthal's Fliegerberg." Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine journeytoberlin.com. Retrieved: 8 January 2012.

- Shlomovitz, Netanel. "Before the Beginning." Israeli Air Force. Retrieved: 8 January 2012.

- "From Lichtenrade to Lichterfelde Süd" (in German) Archived 2012-01-21 at the Wayback Machine Berlin.de. Retrieved: 8 January 2012.

- "Monument to Otto Lilienthal". Nature. 130 (3277): 270. 1932. Bibcode:1932Natur.130R.270.. doi:10.1038/130270b0.

- "Lilienthal Photo archives." Otto Lilienthal Museum. Retrieved: 13 January 2012.

- Harsch, Viktor; Bardrum, Benny; Illig, Petra (October 2008). "Lilienthal's Fatal Glider Crash in 1896: Evidence Regarding the Cause of Death". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 79 (101): 993–994. doi:10.3357/ASEM.2283.2008. PMID 18856192.

- Reichhardt, Tony (August 10, 2016). "The Last Words of Otto Lilienthal". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- Crouch 1989, pp. 226–228.

- Aero Club of America Bulletin, September 1912.

- Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.

- "51 Heroes of Aviation" Flying. Retrieved: March 24, 2019

- "R.E.M. - Losing My Religion (Official Music Video)" (go to 3:06 mark) YouTube. Retrieved: 10 October 2017.

- "The Airship Flying Cloud, R-505." airships.paulgazis.com. Retrieved: 16 November 2012.

- Mey, Reinhard, lyrics: 'Lilienthals Traum' Reinhard Mey. Retrieved: 21 December 2016.

- Lukasch, Bernd. "Lilienthal and Photography." Otto Lilienthal Museum. Retrieved: 13 January 2012.

Bibliography

- Anderson, John D. A History of Aerodynamics and Its Impact on Flying Machines. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, First edition 1999. ISBN 978-0-521-66955-9.

- Crouch, Tom D. The Bishop's Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989. ISBN 0-393-30695-X.

- Lilienthal, Otto. Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation. First edition, 1911 reprinted 2001: ISBN 0-938716-58-1. (Translation from German edition, Berlin 1889: Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst reprinted 2003: ISBN 3-9809023-8-2.)

- Nitsch, Stephan. Vom Sprung zum Flug (From the jump to the flight). Berlin, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, 1991. ISBN 3-327-01090-0. Modified second edition: Die Flugzeuge von Otto Lilienthal. Technik - Dokumentation - Rekonstruktion. (The airplanes of Otto Lilienthal. Technique - Documentation - Reconstruction). Otto-Lilienthal-Museum Anklam, 2016. ISBN 978-3-941681-88-0.

External links

- Biography / family tree of Otto Lilienthal

- Lilienthal's appendix from Chanute's book Progress in Flying Machines 1893.

- Movies and simulations

- "Lilienthal in England" a 1967 Flight article

- Otto Lilienthal at Answers.com

- Otto Lilienthal (1889) Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst - digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library

- Otto Lilienthal (1911) Birdflight as the basis of aviation, compiled from the results of numerous experiments made by O. and G. Lilienthal - digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library

- Newspaper clippings about Otto Lilienthal in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW