Tanggu Truce

The Tanggu Truce, sometimes called the Tangku Truce (Japanese: 塘沽協定, Hepburn: Tōko kyōtei, simplified Chinese: 塘沽协定; traditional Chinese: 塘沽協定; pinyin: Tánggū Xiédìng), was a ceasefire signed between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan in Tanggu District, Tianjin on May 31, 1933. It formally ended the Japanese invasion of Manchuria which had begun two years earlier.

Background

After the Mukden Incident of September 18, 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria, and by February 1932, it had captured the entire region. The last emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Puyi, who was living in exile in the Foreign Concessions in Tianjin, was convinced by the Japanese to accept the throne of the new Empire of Manchukuo, which remained under the control of the Imperial Japanese Army. In January 1933, to secure Manchukuo’s southern borders, a joint Japanese and Manchukuo force invaded Rehe. After conquering that province by March, it drove the remaining Chinese armies in the northeast beyond the Great Wall into Hebei Province.

From the start of hostilities, China had appealed to its neighbors and the international community but received no effective support.[1] When China called an emergency meeting of the League of Nations, a committee was established to investigate the affair. The Lytton Commission's report ultimately condemned Japan's actions but offered no plan for intervention. In response, the Japanese simply withdrew from the League on March 27, 1933.[1][2]

The Japanese army was under explicit instructions from Japanese Emperor Hirohito, who wanted a quick end to the China conflict, not to venture beyond the Great Wall.[3] Its negotiating position was very strong, as the Chinese republicans were under severe pressure from their simultaneous full-scale civil war with the Chinese communists.[1]

Negotiations

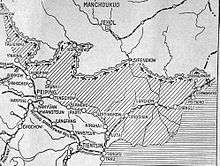

On May 22, 1933, Chinese and Japanese representatives met to negotiate the end of the conflict. The Japanese demands were severe: a demilitarized zone extending 100 km south of the Great Wall from Beijing to Tianjin was to be created, with the Great Wall itself under Japanese control. No regular Kuomintang military units were to be allowed in the demilitarized zone although the Japanese were allowed to use reconnaissance aircraft or ground patrols to ensure that the agreement was maintained. Public order within the zone was to be maintained by a lightly-armed Demilitarized Zone Peace Preservation Corps.

Two secret clauses excluded any of the Anti-Japanese Volunteer Armies from the Peace Preservation Corps and provided for any disputes that could not be resolved by the Peace Preservation Corps to be settled by agreement between the Japanese and the Chinese governments. Harried by their civil war with the communists and unable to win international support, Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese government agreed to virtually all of Japan's demands.[1] Furthermore, the new demilitarized zone was mostly within the remaining territory of the discredited Manchurian warlord Zhang Xueliang.[4]

Aftermath

The Tanggu Truce resulted in the de facto recognition of Manchukuo by the Kuomintang government and acknowledgement of the loss of Rehe.[5] It provided for a temporary end to the combat between China and Japan and relations between the two countries briefly improved. On May 17, 1935, the Japanese legation in China was raised to the status of embassy, and on June 10, 1935, the He-Umezu Agreement was concluded. The Tanggu Truce gave Chiang Kai-shek time to consolidate his forces and to concentrate his efforts against the Chinese Communist Party, albeit at the expense of northern China.[5]

However, Chinese public opinion was hostile to terms so favorable to Japan and so humiliating to China. Although the truce provided for a demilitarized buffer zone, Japanese territorial ambitions towards China remained, and the truce proved to be only a temporary respite until hostilities erupted again with the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

See also

- Unequal treaties

- Japanese imperialism

References

- Kitchen, p. 140–141.

- Van Ginneken, p. 115.

- http://www.republicanchina.org/war.htm#Chang-Cheng-Zhi-Zhan Battles of the Great Wall

- Fenby, p. 282.

- Bix, p. 272.

Sources

- Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

- Fenby, Jonathan (2003). Chiang Kai-shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1318-6.

- Hane, Mikiso (2001). Modern Japan: A Historical Survey. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3756-9.

- Kitchen, Martin (1990). A World in Flames: A Short History of the Second World War in Europe and Asia, 1939–1945. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-03407-8.

- Van Ginneken, Anique H. M. (2006). Historical Dictionary of the League of Nations. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810865136.