Andromeda (constellation)

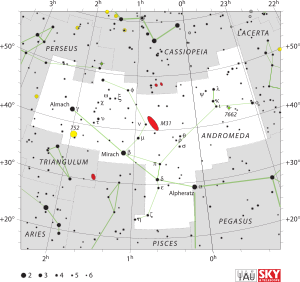

Andromeda is one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century Greco-Roman astronomer Ptolemy and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. Located north of the celestial equator, it is named for Andromeda, daughter of Cassiopeia, in the Greek myth, who was chained to a rock to be eaten by the sea monster Cetus. Andromeda is most prominent during autumn evenings in the Northern Hemisphere, along with several other constellations named for characters in the Perseus myth. Because of its northern declination, Andromeda is visible only north of 40° south latitude; for observers farther south, it lies below the horizon. It is one of the largest constellations, with an area of 722 square degrees. This is over 1,400 times the size of the full moon, 55% of the size of the largest constellation, Hydra, and over 10 times the size of the smallest constellation, Crux.

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | And[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Andromedae |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Symbolism | Andromeda, the Chained Woman[2] |

| Right ascension | 23h 25m 48.6945s– 02h 39m 32.5149s[3] |

| Declination | 53.1870041°–21.6766376°[3] |

| Area | 722[4] sq. deg. (19th) |

| Main stars | 16 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 65 |

| Stars with planets | 12 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 3 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 3 |

| Brightest star | α And (Alpheratz) (2.07m) |

| Messier objects | 3[5] |

| Meteor showers | Andromedids (Bielids) |

| Bordering constellations | |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −40°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of November. | |

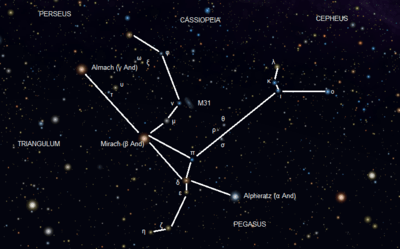

Its brightest star, Alpha Andromedae, is a binary star that has also been counted as a part of Pegasus, while Gamma Andromedae is a colorful binary and a popular target for amateur astronomers. Only marginally dimmer than Alpha, Beta Andromedae is a red giant, its color visible to the naked eye. The constellation's most obvious deep-sky object is the naked-eye Andromeda Galaxy (M31, also called the Great Galaxy of Andromeda), the closest spiral galaxy to the Milky Way and one of the brightest Messier objects. Several fainter galaxies, including M31's companions M110 and M32, as well as the more distant NGC 891, lie within Andromeda. The Blue Snowball Nebula, a planetary nebula, is visible in a telescope as a blue circular object.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars that make up Andromeda were members of four different constellations that had astrological and mythological significance; a constellation related to Andromeda also exists in Hindu mythology. Andromeda is the location of the radiant for the Andromedids, a weak meteor shower that occurs in November.

History and mythology

The uranography of Andromeda has its roots most firmly in the Greek tradition, though a female figure in Andromeda's location had appeared earlier in Babylonian astronomy. The stars that make up Pisces and the middle portion of modern Andromeda formed a constellation representing a fertility goddess, sometimes named as Anunitum or the Lady of the Heavens.[7]

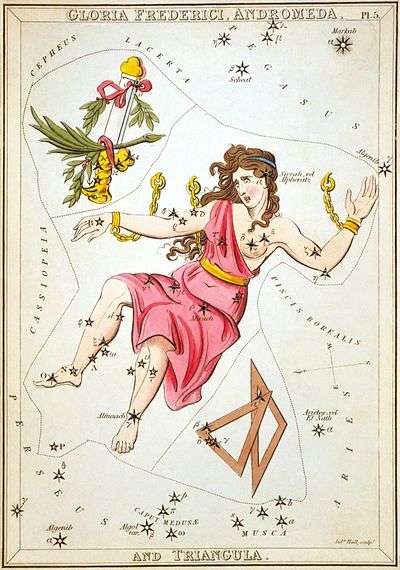

Andromeda is known as "the Chained Lady" or "the Chained Woman" in English. It was known as Mulier Catenata ("chained woman") in Latin and al-Mar'at al Musalsalah in Arabic.[2] It has also been called Persea ("Perseus's wife") or Cepheis ("Cepheus's daughter"),[2][8] all names that refer to Andromeda's role in the Greco-Roman myth of Perseus, in which Cassiopeia, the queen of Ethiopia, bragged that her daughter was more beautiful than the Nereids, sea nymphs blessed with incredible beauty.[9] Offended at her remark, the nymphs petitioned Poseidon to punish Cassiopeia for her insolence, which he did by commanding the sea monster Cetus to attack Ethiopia.[9] Andromeda's panicked father, Cepheus, was told by the Oracle of Ammon that the only way to save his kingdom was to sacrifice his daughter to Cetus.[10][11] She was chained to a rock by the sea but was saved by the hero Perseus, who in one version of the story used the head of Medusa to turn the monster into stone;[12] in another version, by the Roman poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses, Perseus slew the monster with his diamond sword.[11] Perseus and Andromeda then married; the myth recounts that the couple had nine children together – seven sons and two daughters – and founded Mycenae and its Persideae dynasty. After Andromeda's death Athena placed her in the sky as a constellation, to honor her. Several of the neighboring constellations (Perseus, Cassiopeia, Cetus, and Cepheus) also represent characters in the Perseus myth.[10] It is connected with the constellation Pegasus.

Andromeda was one of the original 48 constellations formulated by Ptolemy in his 2nd-century Almagest, in which it was defined as a specific pattern of stars. She is typically depicted with α Andromedae as her head, ο and λ Andromedae as her chains, and δ, π, μ, Β, and γ Andromedae representing her body and legs. However, there is no universal depiction of Andromeda and the stars used to represent her body, head, and chains.[13] Arab astronomers were aware of Ptolemy's constellations, but they included a second constellation representing a fish at Andromeda's feet.[14] Several stars from Andromeda and most of the stars in Lacerta were combined in 1787 by German astronomer Johann Bode to form Frederici Honores (also called Friedrichs Ehre). It was designed to honor King Frederick II of Prussia, but quickly fell into disuse.[15] Since the time of Ptolemy, Andromeda has remained a constellation and is officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union, although like all modern constellations, it is now defined as a specific region of the sky that includes both Ptolemy's pattern and the surrounding stars.[16][17] In 1922, the IAU defined its recommended three-letter abbreviation, "And".[18] The official boundaries of Andromeda were defined in 1930 by Eugène Delporte as a polygon of 36 segments. Its right ascension is between 22h 57.5m and 2h 39.3m and its declination is between 53.19° and 21.68° in the equatorial coordinate system.[3]

In non-Western astronomy

In traditional Chinese astronomy, nine stars from Andromeda (including Beta Andromedae, Mu Andromedae, and Nu Andromedae), along with seven stars from Pisces, formed an elliptical constellation called "Legs" (奎宿). This constellation either represented the foot of a walking person or a wild boar.[11] Gamma Andromedae and its neighbors were called "Teen Ta Tseang Keun" (天大将军, heaven's great general), representing honor in astrology and a great general in mythology.[8][11] Alpha Andromedae and Gamma Pegasi together made "Wall" (壁宿), representing the eastern wall of the imperial palace and/or the emperor's personal library. For the Chinese, the northern swath of Andromeda formed a stable for changing horses (tianjiu, 天厩, stable on sky) and the far western part, along with most of Lacerta, became Tengshe, a flying snake.[11]

An Arab constellation called "al-Hut" (the fish) was composed of several stars in Andromeda, M31, and several stars in Pisces. ν And, μ And, β And, η And, ζ And, ε And, δ And, π And, and 32 And were all included from Andromeda; ν Psc, φ Psc, χ Psc, and ψ Psc were included from Pisces.[14]

Hindu legends surrounding Andromeda are similar to the Greek myths. Ancient Sanskrit texts depict Antarmada chained to a rock, as in the Greek myth. Scholars believe that the Hindu and Greek astrological myths were closely linked; one piece of evidence cited is the similarity between the names "Antarmada" and "Andromeda".[8]

Andromeda is also associated with the Mesopotamian creation story of Tiamat, the goddess of Chaos. She bore many demons for her husband, Apsu, but eventually decided to destroy them in a war that ended when Marduk killed her. He used her body to create the constellations as markers of time for humans.[8][13]

In the Marshall Islands, Andromeda, Cassiopeia, Triangulum, and Aries are incorporated into a constellation representing a porpoise. Andromeda's bright stars are mostly in the body of the porpoise; Cassiopeia represents its tail and Aries its head.[13] In the Tuamotu islands, Alpha Andromedae was called Takurua-e-te-tuki-hanga-ruki, meaning "Star of the wearisome toil",[19] and Beta Andromedae was called Piringa-o-Tautu.[20]

Features

Stars

- α And (Alpheratz, Sirrah) is the brightest star in this constellation. It is an A0p class[9] binary star with an overall apparent visual magnitude of 2.1 and a luminosity of 96 L☉.[21] It is 97 light-years from Earth.[22] It represents Andromeda's head in Western mythology, however, the star's traditional Arabic names – Alpheratz and Sirrah, from the phrase surrat al-faras – [14] sometimes translated as "navel of the steed".[11][23][24] The Arabic names are a reference to the fact that α And forms an asterism known as the "Great Square of Pegasus" with three stars in Pegasus: α, β, and γ Peg. As such, the star was formerly considered to belong to both Andromeda and Pegasus, and was co-designated as "Delta Pegasi (δ Peg)", although this name is no longer formally used.[9][11][21]

- β And (Mirach) is a red-hued giant star of type M0[9][25] located in an asterism known as the "girdle". It is 198 light-years away,[25] has a magnitude of 2.06,[26] and a luminosity of 115 L☉.[21] Its name comes from the Arabic phrase al-Maraqq meaning "the loins" or "the loincloth",[24] a phrase translated from Ptolemy's writing. However, β And was mostly considered by the Arabs to be a part of al-Hut, a constellation representing a larger fish than Pisces at Andromeda's feet.[14]

- γ And (Almach) is an orange-hued bright giant star of type K3[9] found at the southern tip of the constellation with an overall magnitude of 2.14.[21] Almach is a multiple star with a yellow primary of magnitude 2.3 and a blue-green secondary of magnitude 5.0, separated by 9.7 arcseconds.[10][11][23] British astronomer William Herschel said of the star: "[the] striking difference in the colour of the two stars, suggests the idea of a sun and its planet, to which the contrast of their unequal size contributes not a little."[27] The secondary, described by Herschel as a "fine light sky-blue, inclining to green",[27] is itself a double star, with a secondary of magnitude 6.3[10] and a period of 61 years.[21] The system is 358 light-years away.[28] Almach was named for the Arabic phrase ʿAnaq al-Ard, which means "the earth-kid", an obtuse reference to an animal that aids a lion in finding prey.[14][24]

- δ And is an orange-hued giant star of type K3[9] orange giant of magnitude 3.3.[26] It is 105 light-years from Earth.[29]

- ι And, κ, λ, ο, and ψ And form an asterism known as "Frederick's Glory", a name derived from a former constellation (Frederici Honores).[15] ι And is a blue-white hued main-sequence star of type B8, 502 light-years from Earth;[30] κ And is a white-hued main-sequence star of type B9 IVn, 168 light-years from Earth;[31] λ And is a yellow-hued giant star of type G8, 86 light-years from Earth;[32] ο And is a blue-white hued giant star of type B6, 679 light-years from Earth;[33] and ψ And is a blue-white hued main-sequence star of type B7, 988 light-years from Earth.[34]

- μ And is a white-hued main-sequence star of type A5 and magnitude 3.9.[26] It is 130 light-years away.[35]

- υ And (Titawin)[36]is a magnitude 4.1[26] binary system that consists of one F-type dwarf and an M-type dwarf. The primary star has a planetary system with four confirmed planets, 0.96 times, 14.57 times, 10.19 times and 1.06 the mass of Jupiter.[37] The system is 44 light-years from Earth.[38]

- ξ And (Adhil) is a binary star 217 light-years away. The primary is an orange-hued giant star of type K0.[39]

- π And is a blue-white hued binary star of magnitude 4.3[26] that is 598 light-years away. The primary is a main-sequence star of type B5.[40] Its companion star is of magnitude 8.9.[26]

- 51 And (Nembus[36]) was assigned by Johann Bayer to Perseus, where he designated it "Upsilon Persei (υ Per)", but it was moved to Andromeda by the International Astronomical Union.[41] It is 177 light-years from Earth and is an orange-hued giant star of type K3.[42]

- 54 And was a former designation for φ Per.[11][41]

- 56 And is an optical binary star. The primary is a yellow-hued giant star of type K0 with an apparent magnitude of 5.7[26] that is 316 light-years away.[43] The secondary is an orange-hued giant star of type K0 and magnitude 5.9 that is 990 light-years from Earth.[26]

- R And is a Mira-type variable star with a period of 409 days. Its maximum magnitude is 5.8 and its minimum magnitude is 14.8,[9] and it is at a distance of 1,250 light-years.[44] There are 6 other Mira variables in Andromeda.[21]

- Z And is the M-type prototype for its class of variable stars. It ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 12.4 to a maximum of 8.0.[21] It is 2,720 light-years away.[45]

- Ross 248 (HH Andromedae) is the ninth-closest star to Earth at a distance of 10.3 light-years.[46] It is a red-hued main-sequence BY Draconis variable star of type M6.[47]

- 14 And (Veritate[36]) is a yellow-hued giant star of type G8 that is 251 light-years away.[48] It has a mass of 2.2 M☉ and a radius of 11 R☉. It has one planet, 14 Andromedae b, discovered in 2008. It orbits at a distance of 0.83 astronomical units from its parent star every 186 days and has a mass of 4.3 MJ.[49]

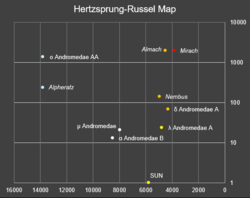

Of the stars brighter than 4th magnitude (and those with measured luminosity), Andromeda has a relatively even distribution of evolved and main-sequence stars.

Deep-sky objects

The constellation of Andromeda lies well away from the galactic plane, so it does not contain any of the open clusters or bright nebulae of the Milky Way. Because of its distance in the sky from the band of obscuring dust, gas, and abundant stars of our home galaxy, Andromeda's borders contain many visible distant galaxies.[10] The most famous deep-sky object in Andromeda is the spiral galaxy cataloged as Messier 31 (M31) or NGC 224 but known colloquially as the Andromeda Galaxy for the constellation.[50] M31 is one of the most distant objects visible to the naked eye, 2.2 million light-years from Earth (estimates range up to 2.5 million light-years)[51]. It is seen under a dark, transparent sky as a hazy patch in the north of the constellation.[51] M31 is the largest neighboring galaxy to the Milky Way and the largest member of the Local Group of galaxies.[50][51] In absolute terms, M31 is approximately 200,000 light-years in diameter, twice the size of the Milky Way.[51] It is an enormous – 192.4 by 62.2 arcminutes in apparent size[10] – barred spiral galaxy similar in form to the Milky Way and at an approximate magnitude of 3.5, is one of the brightest deep-sky objects in the northern sky.[52] Despite being visible to the naked eye, the "little cloud" near Andromeda's figure was not recorded until AD 964, when the Arab astronomer al-Sufi wrote his Book of Fixed Stars.[11][53] M31 was first observed telescopically shortly after its invention, by Simon Marius in 1612.[54]

The future of the Andromeda and Milky Way galaxies may be interlinked: in about five billion years, the two could potentially begin an Andromeda–Milky Way collision that would spark extensive new star formation.[51]

American astronomer Edwin Hubble included M31 (then known as the Andromeda Nebula) in his groundbreaking 1923 research on galaxies.[53] Using the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory in California, he observed Cepheid variable stars in M31 during a search for novae, allowing him to determine their distance by using the stars as standard candles.[56] The distance he found was far greater than the size of the Milky Way, which led him to the conclusion that many similar objects were "island universes" on their own.[57][58][59] Hubble originally estimated that the Andromeda Galaxy was 900,000 light-years away, but Ernst Öpik's estimate in 1925 put the distance closer to 1.5 million light-years.[56]

The Andromeda Galaxy's two main companions, M32 and M110 (also known as NGC 221 and NGC 205, respectively) are faint elliptical galaxies that lie near it.[5][50] M32, visible with a far smaller size of 8.7 by 6.4 arcminutes,[10] compared to M110, appears superimposed on the larger galaxy in a telescopic view as a hazy smudge, M110 also appears slightly larger and distinct from the larger galaxy;[50] M32 is 0.5° south of the core, M32 is 1° northwest of the core.[26] M32 was discovered in 1749 by French astronomer Guillaume Le Gentil and has since been found to lie closer to Earth than the Andromeda Galaxy itself.[60] It is viewable in binoculars from a dark site owing to its high surface brightness of 10.1 and overall magnitude of 9.0.[10] M110 is classified as either a dwarf spheroidal galaxy or simply a generic elliptical galaxy. It is far fainter than M31 and M32, but larger than M32 with a surface brightness of 13.2, magnitude of 8.9, and size of 21.9 by 10.9 arcminutes.[10]

The Andromeda Galaxy has a total of 15 satellite galaxies, including M32 and M110. Nine of these lie in a plane, which has caused astronomers to infer that they have a common origin. These satellite galaxies, like the satellites of the Milky Way, tend to be older, gas-poor dwarf elliptical and dwarf spheroidal galaxies.[61]

Along with the Andromeda Galaxy and its companions, the constellation also features NGC 891 (Caldwell 23), a smaller galaxy just east of Almach. It is a barred spiral galaxy seen edge-on, with a dark dust lane visible down the middle. NGC 891 is incredibly faint and small despite its magnitude of 9.9,[21] as its surface brightness of 14.6 indicates;[10] it is 13.5 by 2.8 arcminutes in size.[21] NGC 891 was discovered by the brother-and-sister team of William and Caroline Herschel in August 1783.[51] This galaxy is at an approximate distance of 30 million light-years from Earth, calculated from its redshift of 0.002.[51]

Andromeda's most celebrated open cluster is NGC 752 (Caldwell 28) at an overall magnitude of 5.7.[21] It is a loosely scattered cluster in the Milky Way that measures 49 arcminutes across and features approximately twelve bright stars, although more than 60 stars of approximately 9th magnitude become visible at low magnifications in a telescope.[10][26] It is considered to be one of the more inconspicuous open clusters.[9] The other open cluster in Andromeda is NGC 7686, which has a similar magnitude of 5.6 and is also a part of the Milky Way. It contains approximately 20 stars in a diameter of 15 arcminutes, making it a tighter cluster than NGC 752.[21]

There is one prominent planetary nebula in Andromeda: NGC 7662 (Caldwell 22).[21] Lying approximately three degrees southwest of Iota Andromedae at a distance of about 4,000 light-years from Earth, the "Blue Snowball Nebula"[10] is a popular target for amateur astronomers.[62] It earned its popular name because it appears as a faint, round, blue-green object in a telescope, with an overall magnitude of 9.2.[10][62] Upon further magnification, it is visible as a slightly elliptical annular disk that gets darker towards the center, with a magnitude 13.2 central star.[10][26] The nebula has an overall magnitude of 9.2 and is 20 by 130 arcseconds in size.[21]

Meteor showers

Each November, the Andromedids meteor shower appears to radiate from Andromeda.[63] The shower peaks in mid-to-late November every year, but has a low peak rate of fewer than two meteors per hour.[64] Astronomers have often associated the Andromedids with Biela's Comet, which was destroyed in the 19th century, but that connection is disputed.[65] Andromedid meteors are known for being very slow and the shower itself is considered to be diffuse, as meteors can be seen coming from nearby constellations as well as from Andromeda itself.[66] Andromedid meteors sometimes appear as red fireballs.[67][68] The Andromedids were associated with the most spectacular meteor showers of the 19th century; the storms of 1872 and 1885 were estimated to have a peak rate of two meteors per second (a zenithal hourly rate of 10,000), prompting one Chinese astronomer to compare the meteors to falling rain.[65][69] The Andromedids had another outburst on December 3–5, 2011, the most active shower since 1885, with a maximum zenithal hourly rate of 50 meteors per hour. The 2011 outburst was linked to ejecta from Comet Biela, which passed close to the Sun in 1649. None of the meteoroids observed were associated with material from the comet's 1846 disintegration. The observers of the 2011 outburst predicted outbursts in 2018, 2023, and 2036.[70]

See also

References

Citations

- Russell 1922, p. 469.

- Allen 1899, pp. 32–33.

- IAU, The Constellations, Andromeda.

- Ridpath, Constellations.

- Bakich 1995, p. 54.

- Bakich 1995, p. 26.

- Rogers, Mediterranean Traditions 1998.

- Olcott 2004, pp. 22–23.

- Moore & Tirion 1997, pp. 116–117.

- Thompson & Thompson 2007, pp. 66–73.

- Ridpath, Star Tales Andromeda.

- Pasachoff 2000, p. 132.

- Staal 1988, pp. 7–14, 17.

- Davis 1944.

- Bakich 1995, p. 43.

- Bakich 1995, p. 11.

- Pasachoff 2000, pp. 128–129.

- Russell 1922, pp. 469–471.

- Makemson 1941, p. 255.

- Makemson 1941, p. 279.

- Moore 2000, pp. 328–330.

- SIMBAD Alpha And.

- Ridpath & Tirion 2009, pp. 61–62.

- Odeh & Kunitzsch 1998.

- SIMBAD Mirach.

- Ridpath 2001, pp. 72–74.

- French 2006.

- SIMBAD Gamma1 Andromedae.

- SIMBAD Delta Andromedae.

- SIMBAD Iota And.

- SIMBAD Kappa Andromedae.

- SIMBAD Lambda Andromedae.

- SIMBAD Omicron Andromedae.

- SIMBAD Psi Andromedae.

- SIMBAD 37 Andromedae.

- "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ExoPlanet ups And.

- SIMBAD Ups And.

- SIMBAD Xi Andromedae.

- SIMBAD 29 And.

- Wagman 2003, p. 240.

- SIMBAD 51 And.

- SIMBAD 56 And.

- SIMBAD R And.

- SIMBAD Z And.

- RECONS, The 100 Nearest Star Systems.

- SIMBAD HH And.

- SIMBAD 14 And.

- ExoPlanet Planet 14 And b.

- Pasachoff 2000, p. 244.

- Wilkins & Dunn 2006, pp. 348, 366.

- Bakich 1995, p. 51.

- Higgins 2002.

- Rao 2011.

- "Sharpest ever view of the Andromeda Galaxy". www.spacetelescope.org. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Hoskin & Dewhirst 1999, pp. 292–296.

- ESA, Edwin Powell Hubble.

- PBS, Edwin Hubble 1998.

- HubbleSite, About Edwin Hubble 2008.

- Block 2003.

- Koch & Grebel 2006.

- Pasachoff 2000, p. 270.

- Bakich 1995, p. 60.

- Lunsford, Meteor Shower List 2012.

- Jenniskens 2008.

- Lunsford, Activity Nov 19–23 2011.

- Sherrod & Koed 2003, p. 58.

- Jenniskens & Vaubaillon 2007.

- Jenniskens 2006, p. 384.

- Wiegert et al. 2012.

Bibliography

- Allen, Richard H. (1899). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. G. E. Stechert. OCLC 30773662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bakich, Michael E. (1995). The Cambridge Guide to the Constellations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44921-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, George A. Jr. (1944). "The Pronunciations, Derivations, and Meanings of a Selected List of Star Names". Popular Science. 52: 8. Bibcode:1944PA.....52....8D.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- French, Sue (January 2006). "Winter wonders: star-studded January skies offer deep-sky treats for every size telescope". Sky and Telescope. 111 (1): 83.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (subscription required)

- Higgins, David (November 2002). "Exploring the depths of Andromeda". Astronomy: 88.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koch, A.; Grebel, E. K. (March 2006). "The Anisotropic Distribution of M31 Satellite Galaxies: A Polar Great Plane of Early-type Companions". Astronomical Journal. 131 (3): 1405–1415. arXiv:astro-ph/0509258. Bibcode:2006AJ....131.1405K. doi:10.1086/499534.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoskin, Michael; Dewhirst, David (1999). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57291-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenniskens, Peter (2006). Meteor Showers and Their Parent Comets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85349-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58582-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7503-0620-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olcott, William Tyler (2004) [1911]. Star Lore: Myths, Legends, and Facts. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43581-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pasachoff, Jay M. (2000). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-93431-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rao, Joe (October 2011). "Skylog". Natural History. 119 (9): 42.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (subscription required)

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2009). The Monthly Sky Guide (8th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13369-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ridpath, Ian (2001). Stars and Planets Guide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08913-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (2): 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

- Russell, Henry Norris (October 1922). "The new international symbols for the constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherrod, P. Clay; Koed, Thomas L. (2003). A Complete Manual of Amateur Astronomy: Tools and Techniques for Astronomical Observations. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42820-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Hubble Essentials: About Edwin Hubble". HubbleSite. Space Telescope Science Institute. 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Staal, Julius D.W. (1988). The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars (2nd ed.). The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-04-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Robert Bruce; Thompson, Barbara Fritchman (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars. McDonald and Woodward Publishing. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe (1st ed.). Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Online sources

- Block, Adam (17 October 2003). "M32". Kitt Peak National Observatory. Retrieved 14 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Star: ups And". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- "Planet 14 And b". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Edwin Powell Hubble – The man who discovered the cosmos". European Space Agency. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Andromeda constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Jenniskens, Peter (3 April 2008). "The Mother of All Meteor Storms". Space.com. Retrieved 2 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenniskens, P.; Vaubaillon, J. (2007). "3D/Biela and the Andromedids: Fragmenting versus Sublimating Comets". The Astronomical Journal. 134 (3): 1037. Bibcode:2007AJ....134.1037J. doi:10.1086/519074.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lunsford, Robert (17 November 2011). "Meteor Activity Outlook for November 19–23, 2011". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Lunsford, Robert (16 January 2012). "2012 Meteor Shower List". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Odeh, Moh'd; Kunitzsch, Paul (1998). "ICOP: Arabic Star Names". Islamic Crescents' Observation Project. Retrieved 1 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Edwin Hubble". A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries. PBS. 1998. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "The 100 Nearest Star Systems". Research Consortium on Nearby Stars. 1 January 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations". Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Andromeda". Star Tales. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Wiegert, Paul A.; Brown, Peter G.; Weryk, Robert J.; Wong, Daniel K. (22 September 2012). "The return of the Andromedids meteor shower". The Astronomical Journal. 145 (3): 70. arXiv:1209.5980. Bibcode:2013AJ....145...70W. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/145/3/70.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Alpha And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Mirach". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Gamma1 Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Delta Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Iota And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Kappa Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Lambda Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Omicron Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Psi Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "37 Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Ups And – High proper-motion Star". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Xi Andromedae". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "29 And (Pi And)". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "51 And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "56 And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "R And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Z And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- "HH And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "14 And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

External links

![]()

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Andromeda

- The clickable Andromeda

- Star Tales – Andromeda

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (over 170 medieval and early modern images of Andromeda)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 975.