Allegheny Observatory

The Allegheny Observatory is an American astronomical research institution, a part of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Pittsburgh. The facility is listed on the National Register of Historical Places (ref. # 79002157, added June 22, 1979)[3] and is designated as a Pennsylvania state[4] and Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation[5] historic landmark.

The observatory in 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Organization | University of Pittsburgh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observatory code | 778 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

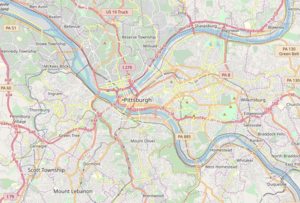

| Location | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40.482525°N 80.020829°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Established | February 15, 1859 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Allegheny Observatory | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Telescopes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Location of Allegheny Observatory | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

.jpg)

The observatory was founded on February 15, 1859, in the city of Allegheny, Pennsylvania (incorporated into the City of Pittsburgh in 1907) by a group of wealthy industrialists calling themselves the Allegheny Telescope Association. The observatory's initial purpose was for general public education as opposed to research, but by 1867 the revenues derived from this had receded. The facility was then donated to the Western University of Pennsylvania, today known as the University of Pittsburgh.

The University hired Samuel Pierpont Langley to be the first director. One of the research programs initiated under his leadership was of sunspots. He drew very detailed drawings of sunspots which are still used in astronomical textbooks to this day. He also had the building expanded to include dark rooms, class rooms, dormitories, and a lecture hall.

In 1869, Langley created income for observatory by selling subscription service to time that was accurately determined by astronomical measurements and transmitted over telegraphs to customers. The Pennsylvania Railroad was the most influential subscriber to the "Allegheny Time" system. The Allegheny Observatory's service is believed to have been the first regular and systematic system of time distribution to railroads and cities as well as the origin of the modern standard time system.[6] By 1870, the Allegheny Time service extended over 2,500 miles with 300 telegraph offices receiving time signals.[7] On November 18, 1883, the first day of railroad standard time in North America, the Allegheny Observatory transmitted a signal on telegraph lines operated by railroads in Canada and the United States. The signal marked noon, Eastern Standard Time, and railroads across the continent synchronized their schedules based on this signal. The standard time that began on this day continues in North American use to this day.[8]

The revenues from the sale of time signals covered Langley's salary and the bills. Allegheny Observatory continued to supply time signals until the US Naval Observatory started offering it for free in 1920.

More recently George Gatewood began using the Allegheny Observatory to search for extrasolar planets as well as to follow up on claims of extrasolar planets, starting in 1972.[9] This is done using astrometry, which is the practice of measuring the position of stars. In addition to studying the positions of stars on the thousands of photographic plates in the vaults of the observatory, George Gatewood also designed the Multichannel Astrometric Photometer (MAP) for use with the Thaw telescope to measure the position of a target star and its close neighbors on images taken 6 months apart. This technique takes advantage of parallax. If the target star has a companion then it will wobble due to the gravitational pull of the unseen companion. The size of the companion can be measured by the size of the wobble.

MAP is no longer in use and the Thaw telescope is in the process of rewiring and upgrading.

A model of the original observatory can be found in the Miniature Railroad & Village exhibit at Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh and in 2012 a documentary film was released covering the observatory's history.[10]

The Lens-napping

Langley was the director when he returned home in Allegheny City on July 8, 1872, following a conference. Observatory staff advised him that the lens of the 13 inch Fitz Telescope had been taken for ransom which Langley refused to pay; an argument with the unknown lens-napper ensued without resolve. It has been speculated that Langley knew the identity of the lens-napper, his or her identity is still a mystery. The lens-napper thought that with the involvement of the newspapers investigating the incidents his identity may be discovered so told Langley he could have back the lens. No clue was given as to its location but it was eventually found in a Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, hotel wastepaper basket. It being scratched made it useless so it was re-ground by lens maker Alvan Clark. When it was reinstalled the clarity was improved so the lens-napping benefited the observatory. In gratitude, Langley added Clark's name to the telescope.[11]

Heavier-than-air flight research

Langley also researched heavier-than-air flight behind the observatory. To study the aerodynamic behavior of different forms traveling at high speeds he built a large spring "whirling arm" to which stuffed birds and wings he made were attached. After leaving Allegheny Observatory to become secretary of the Smithsonian in 1888, he continued his flight research, designing and flying the first, unmanned, aircraft capable of stable continuously powered flight from a houseboat on the Potomac River. His full-size manned Aerodrome was funded by the U.S. Army. Two well-publicized crashes of the Aerodrome in 1903 ended his flight research.

The New Allegheny Observatory

The original observatory building was replaced by the current structure, shown in the photograph above. It was designed in the Classic Revival style by Thorsten E. Billquist. The cornerstone was laid in 1900, and the new structure was completed in 1912. It is located four miles north of downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at Riverview Park. The building is a tan brick and white terra cotta hilltop temple whose Classical forms and decoration symbolize the unity of art and science. The L-shaped building consists of a library, lecture hall, classrooms, laboratories, offices, and three hemispherical domed telescope enclosures. Two were reserved for research; one for use by schools and the general public. The core of the building is a small rotunda, housing an opalescent glass window depicting the Greek muse of astronomy, Urania,[12] designed by artist Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast.[13] A crypt in the basement of the observatory holds the ashes of two eminent astronomers and former directors of the Allegheny Observatory, James Edward Keeler and John Brashear. In addition, the crypt holds the remains of Brashear's wife Phoebe and Keeler's wife Cora Matthews Keeler and son Henry Bowman Keeler.[14]

The original observatory building was converted into an athletics training facility in 1907 and used by the university's football team.[15][16] The original observatory building was sold, along with the rest of the adjacent university buildings, to the Protestant Orphan Asylum prior to the move of the main academic portion of the university to the Oakland section of Pittsburgh in 1909.[17] The original observatory building was torn down in the 1950s and the site is now occupied by Triangle Tech.

Current work

The main active research pursuit at the Allegheny Observatory involves detections of extrasolar planets.[18] This is done using photometry, which is the practice of measuring the brightness of stars. The brightness of a target star and its close neighbors are measured on digital images taken every 30–60 seconds, and if a planet crosses (transits) in front of its parent star's disk, then the observed visual brightness of the star drops a small amount. The amount the star dims depends on the relative sizes of the star and the planet. The research team consists of students at the University of Pittsburgh whose observations have recently contributed to a collaborative effort to observe a transit of the planet HD 80606 b.[19] The group is also actively contributing to upgrading the Allegheny Observatory.

In 2009, the university's Department of Geology and Planetary Science installed Western Pennsylvania's only seismic station, which is connected to IRIS Consortium networks, in the observatory.[20]

Tours

When the new Allegheny Observatory was designed it was done with the public in mind; the floor plan included a lecture hall. When the new facility first went into operation, on every clear evening it was opened for the public to look through the 13" telescope but if it were a cloudy night "they would be given an illustrated lecture on astronomy." John Brashear once said "the Allegheny observatory would remain forever free to the people" and to this day it has[21] although in modern times the free public tours are only offered a couple nights each week.

See also

- List of astronomical observatories

- Samuel Pierpont Langley, Allegheny Observatory's first director.

- James Edward Keeler

- John A. Brashear

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Allegheny Observatory – PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Allegheny Observatory" (PDF). July 21, 1977. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Allegheny Observatory". Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission: Historical Markers Program. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- "Internet Archive: Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation: PHLF Plaques & Registries". January 27, 2007. Archived from the original on January 27, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- Walcott, Charles Doolittle (April 1912). Biographical Memoir of Samuel Pierpont Langley, 1834–1906. National Academy of Sciences. p. 248.

- Butowsky, Harry (1989). "Allegheny Observatory". Astronomy and Astrophysics. National Park Service. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- Parkinson, J. Robert (February 15, 2004). "When it comes to time zones in the United States, it's all business". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 25, 2006. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- Alan Boss (1998). Looking For Earths. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Vancheri, Barbara (April 20, 2012). "Film Notes: 'Undaunted' shows pioneers who reached for the stars at Allegheny Observatory". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- "Fitz-Clark Telescope at Allegheny Observatory Website".

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070822115959/http://wordpress.phlf.org/wordpress/?cat=22

- "Mary E. Tillinghast and Urania, The Muse of Astronomy". Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Zapadka, Pete. "Crypt at Allegheny Observatory". YouTube. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- Davis, C. E., ed. (October 1907). "Athletics". Courant. 23 (1): 16. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- The Owl. Pittsburgh, PA: Junior Class of Western University of Pennsylvania. 1909. p. 240. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- Starrett, Agnes Lynch (1937). Through One Hundred and Fifty Years: the University of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 219. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- Schmitt, Ben (Fall 2014). "The Awe of Night". Pittsburgh Quarterly. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Shporer, A; Winn, J. N; Dreizler, S; Colon, K. D; Wood-Vasey, W. M; Choi, P. I; Morley, C; Moutou, C; Welsh, W. F; Pollaco, D; Starkey, D; Adams, E; Barros, S. C. C; Bouchy, F; Cabrera-Lavers, A; Cerutti, S; Coban, L; Costello, K; Deeg, H; Diaz, R. F; Esquerdo, G. A; Fernandez, J; Fleming, S. W; Ford, E. B; Fulton, B. J; Good, M; Hebrard, G; Holman, M. J; Hunt, M; et al. (2010). "Ground-based multisite observations of two transits of HD 80606b". The Astrophysical Journal. 722: 880–887. arXiv:1008.4129. Bibcode:2010ApJ...722..880S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/722/1/880.

- Kelly, Morgan (November 2, 2009). "Pitt's New Seismic Station Connects Region With Global Network Of Scientists Unraveling Earth's Structure". Pitt Chronicle. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- Brashear, John A. "John A. Brashear; the autobiography of a man who loved the stars." American Society of mechanical engineers. 1924.

- Toker, Franklin (1994) [1986]. Pittsburgh: An Urban Portrait. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-5434-7.

- Miniature Railroad & Village training manual.

- Allegheny Observatory tour

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Allegheny Observatory. |

.jpg)

- Allegheny Observatory Homepage

- National Park Service history of the observatory with photos

- Photographs from the Allegheny Observatory Collection 1850–1967

- Finding aid to the Allegheny Observatory Records at the Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh

- The Parallax Project on the University of Pittsburgh's Digital Research Library

- 360° panorama of the Thaw Memorial Refractor telescope in the main dome

- Pittsburgh Clear Sky Clock (weather forecast for observing conditions)

Video

- "Undaunted: The Forgotten Giants of the Allegheny Observatory"

- YouTube: Stars and Domes in Motion

- WQED OnQ: Allegheny Observatory

- WQED OnQ: John Brashear's Legacy

| Preceded by Thaw Hall |

University of Pittsburgh Buildings Allegheny Observatory Constructed: 1900–1912 |

Succeeded by Gardner Steel Conference Center |