Alfalfa County, Oklahoma

Alfalfa County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 5,642.[1] The county seat is Cherokee.[2]

Alfalfa County | |

|---|---|

Alfalfa County Courthouse in Cherokee (2007) | |

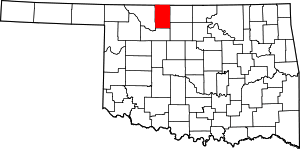

Location within the U.S. state of Oklahoma | |

Oklahoma's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 36°44′N 98°19′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1907 |

| Named for | William H. "Alfalfa Bill" Murray |

| Seat | Cherokee |

| Largest city | Cherokee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 881 sq mi (2,280 km2) |

| • Land | 866 sq mi (2,240 km2) |

| • Water | 15 sq mi (40 km2) 1.7%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018) | 5,754 |

| • Density | 6.5/sq mi (2.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 3rd |

Alfalfa County was formed at statehood in 1907 from Woods County. The county is named after William H. "Alfalfa Bill" Murray, the president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention and ninth governor of Oklahoma. He was instrumental creating the county from the original, much larger Woods county.[3][4]

History

Early history

Indigenous peoples inhabited and hunted in this area for thousands of years. By 1750, the Osage had become a dominant tribe in the area. About one third belonged to the band led by Chief Black Dog (Manka - Chonka). Before 1800 they made the Black Dog Trail starting east of Baxter Springs, Kansas and heading southwest to their summer hunting grounds at the Great Salt Plains in present-day Alfalfa County.[5][6] The Osage stopped at the springs, which attracted migratory birds and varieties of wildlife, for its healing properties on their way to hunting on the plains. The Osage name for this fork of the Arkansas River was Nescatunga (big salt water), what European-Americans later called the Salt Fork.[7] The Osage cleared the trail of brush and large rocks, and made ramps at the fords. Wide enough for eight men riding horses abreast, the trail was the first improved road in Kansas and Oklahoma.[8]

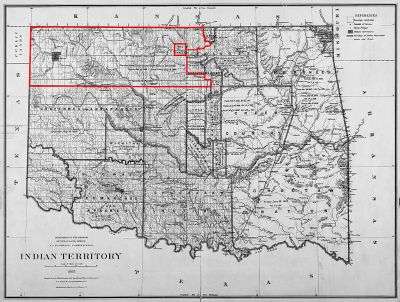

Pre-statehood

The treaties of 1828 and 1835 placed what would later become Alfalfa County within the Cherokee Outlet, which was owned by the Cherokee Nation. Ranching became the primary economic activity from 1870 to 1890; cattle companies that belonged to the Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association leased grazing land from the Cherokee. Prominent rancher, Major Andrew Drumm operated the "U Ranch" here as early as 1870. Its headquarters were southeast of Driftwood on the Medicine Lodge and Salt Fork rivers.[3]

Woods County was created in September 1893 at the same time as the opening of the Cherokee Outlet with the Cherokee Strip Land Run. As population increased and Cherokee land titles were extinguished, the legislature authorized the creation of Alfalfa County in 1907, as part of statehood.[3] The county was named after William H. "Alfalfa Bill" Murray, who served as the president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention and would later be elected as the ninth governor of Oklahoma.[3][4][9] He promoted creation of this county.

Statehood years onward

The city of Cherokee, was designated as the county seat after being chosen by voters in an election held in January 1909. Other towns receiving votes for the honor were Carmen, Ingersoll, and Jet.[3]

Alfalfa County's population was primarily of European-American ancestry. European immigrants and their children were numerous in the early 1900s. Germans from Russia (ethnic Germans who immigrated to American from Russia), many of whom were Mennonites, settled near Ingersoll, Driftwood, Cherokee, and Goltry. Early censuses also reveal a considerable number of Bohemians from the Austro-Hungary Empire. At the turn of the twenty-first century, nearly 17 percent of county residents claimed German ancestry on the census.[3] One Mennonite church (in Goltry) remained as of 2006.[10]

Early railroad construction, from the Choctaw Northern line (1901), the Kansas City, Mexico and Orient (1901), the Arkansas Valley and Western (1904), and the Denver, Enid and Gulf Railroad Company (1904), contributed greatly to the county's early prosperity and caused many small towns to flourish. They would compete as wheat-shipping points and agribusiness centers for many years thereafter.[3] However, by 2000 only one rail line, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe, served the county.[3]

Petroleum exploration and production has been an contributor to Alfalfa County's economy since the time of statehood. Agricultural pursuits, including wheat farming and livestock raising, were major contributors to Alfalfa County's economy during the twentieth century. Small-scale agriculture in its early years supported dozens of towns and dispersed rural communities, many of which no longer exist as a result of transportation and economic changes. After construction of railroads, those towns bypassed by rail service, such as Carroll, Carwile, Keith, and Timberlake, did not prosper for long.

Restructuring of the railroad industry in the late 20th century resulted in abandonment of other lines, and towns such as Ingersoll and Driftwood, for example, had declining populations that made it difficult to sustain educational and city services. Ingersoll (founded 1901) peaked in 1910 with 253 inhabitants and Driftwood (founded 1898) in 1930 with 71. By 1980, neither of these towns was still incorporated. Aline, Amorita, Burlington, Byron, Carmen, Cherokee, Goltry, Helena, Jet, and Lambert remained incorporated as of 2000.[3]

Economy

The largely rural economy is based on agricultural and energy production. Agriculture has altered to be based in industrial-scale farms and production. The county is the second-largest producer of winter wheat in Oklahoma. The USDA estimated the county's winter wheat production at 5,957,000 bushels for 2015.[11] The USDA also listed the county as the state's seventh-largest producer of sorghum in 2015, at 702,000 bushels.[12]

Alfalfa County remains a major producer of petroleum and natural gas. In 2012, it was second (surpassed only by neighboring Woods County) in production of natural gas for Oklahoma counties, with an output of 419,606,514 Mcf (thousand cubic feet). It is also a major producer of crude oil, with total output of 3,395,396 barrels in 2012, which was fifth among Oklahoma counties.[13][14][15]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 881 square miles (2,280 km2), of which 866 square miles (2,240 km2) is land and 15 square miles (39 km2) (1.7%) is water.[16] The Great Salt Plains Lake, as well as the associated Great Salt Plains State Park and Great Salt Plains National Wildlife Refuge lie within the county, approximately 12 miles east of Cherokee.[17] The major waterways in the county are the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River and the Medicine Lodge River.[18]

It is part of the Red Bed plains.

Major highways

Adjacent counties

- Harper County, Kansas (northeast)

- Grant County (east)

- Garfield County (southeast)

- Major County (south)

- Woods County (west)

- Barber County, Kansas (northwest)

National protected area

State Park

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 18,138 | — | |

| 1920 | 16,253 | −10.4% | |

| 1930 | 15,228 | −6.3% | |

| 1940 | 14,129 | −7.2% | |

| 1950 | 10,699 | −24.3% | |

| 1960 | 8,445 | −21.1% | |

| 1970 | 7,224 | −14.5% | |

| 1980 | 7,077 | −2.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,416 | −9.3% | |

| 2000 | 6,105 | −4.8% | |

| 2010 | 5,642 | −7.6% | |

| Est. 2018 | 5,754 | [19] | 2.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] 1790-1960[21] 1900-1990[22] 1990-2000[23] 2010-2015[24] | |||

As of the 2010 census, Alfalfa County had a population of 5,642 people, down from 6,105 people in 2000. Most of the population (89.1%) self-identified as white. Black or African American individuals made up 4.7% of the population and Native Americans made up 2.9% of the population. Less than 1% of the population was Asian.[1]

The median age of the population was 46 years and 18% of the county's population was under the age of 18. Individuals 65 years of age or older accounted for 20.2% of the population.[1]

There were a total of 2,022 households and 1,333 families in the county in 2010. There were 2,763 housing units. Of the 2,022 households, 23.4 percent included children under the age of 18 and slightly more than half (56.3%) included married couples living together. Non-family households accounted for 34.1% of households. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.81.[1]

The median income for a household in the county was $42,730, and the median income for a family was $56,444. The per capita income for the county was $24,080. About 7 percent of families and 11 percent of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.4 percent of those age 65 or over.[1]

Notable people born in Alfalfa County

- R. Orin Cornett (1913 – 2002), physicist, was born in Driftwood. He earned a doctorate of physics and applied mathematics from the University of Texas in 1940, and invented the communication system for the hearing impaired known as Cued Speech. He taught at Oklahoma Baptist University, Penn State, and Harvard University. He also served as a vice president at Oklahoma Baptist and as the Vice President of Long Range Planning for Gallaudet University.[25][26]

- Beryl Clark (1917 – 2000), born in Cherokee. Clark was a football player with the Oklahoma Sooners who was selected as a second-team halfback on the 1939 College Football All-America Team.[27] Clark was drafted by the Chicago Cardinals in the 1940 NFL Draft and played for the Cardinals during the 1940 NFL season.[28]

- Harold Keith (1903 – 1998), born in Lambert.[29] He earned a master's degree in history and became the University of Oklahoma's first sports publicist from 1930 to 1969.[30] He was awarded the 1958 Newbery Medal for his historical novel Rifles for Watie, which is based on the interviews he did for his Master's thesis.[29] Keith was a 1987 inductee into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame (now a part of the Jim Thorpe Association).[31]

- Harold G. Kiner (1924 – 1944), was born in Aline. As a private in the US Army during World War II, he received the U. S. military's highest decoration — the Medal of Honor — for his heroic actions.

- Wallace "Wally" Parks (1913 – 2007) was born in Goltry. Parks was founder in 1951, chairman and president of the National Hot Rod Association, better known as NHRA. It helped establish drag racing as a legitimate amateur and professional motorsport. In 1948, he was named editor of Hot Rod magazine. Parks was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1992 and the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in 1993.[32]

Politics

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of November 1, 2019[33] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 519 | 18.66% | |||

| Republican | 2,026 | 72.85% | |||

| Others | 222 | 7.98% | |||

| Total | 2,781 | 100% | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 85.6% 1,933 | 9.6% 216 | 4.8% 109 |

| 2012 | 84.5% 1,761 | 15.5% 322 | |

| 2008 | 83.1% 2,023 | 16.9% 411 | |

| 2004 | 82.4% 2,201 | 17.6% 470 | |

| 2000 | 75.2% 1,886 | 23.3% 583 | 1.5% 38 |

| 1996 | 56.5% 1,504 | 29.9% 796 | 13.6% 363 |

| 1992 | 51.5% 1,567 | 24.3% 741 | 24.2% 737 |

| 1988 | 62.6% 1,960 | 35.7% 1,117 | 1.8% 55 |

| 1984 | 75.3% 2,715 | 24.0% 866 | 0.8% 27 |

| 1980 | 72.2% 2,628 | 24.7% 899 | 3.2% 115 |

| 1976 | 54.2% 2,113 | 44.3% 1,725 | 1.5% 59 |

| 1972 | 81.5% 3,208 | 16.3% 641 | 2.2% 88 |

| 1968 | 69.5% 2,672 | 22.5% 865 | 8.1% 310 |

| 1964 | 58.6% 2,450 | 41.4% 1,730 | |

| 1960 | 75.7% 3,332 | 24.3% 1,067 | |

| 1956 | 70.3% 3,251 | 29.7% 1,371 | |

| 1952 | 78.8% 4,155 | 21.2% 1,118 | |

| 1948 | 60.1% 2,765 | 39.9% 1,838 | |

| 1944 | 66.3% 3,434 | 33.1% 1,716 | 0.6% 32 |

| 1940 | 56.9% 3,675 | 42.1% 2,720 | 0.9% 60 |

| 1936 | 42.7% 2,573 | 56.4% 3,398 | 0.9% 55 |

| 1932 | 35.9% 2,037 | 64.1% 3,642 | |

| 1928 | 78.0% 4,224 | 20.1% 1,086 | 2.0% 107 |

| 1924 | 57.3% 2,967 | 30.1% 1,558 | 12.7% 656 |

| 1920 | 63.7% 3,005 | 28.6% 1,350 | 7.7% 362 |

| 1916 | 41.6% 1,378 | 41.9% 1,390 | 16.5% 546 |

| 1912 | 50.7% 1,714 | 34.9% 1,179 | 14.4% 485 |

Communities

City

- Cherokee (county seat)

Census-designated place

Other unincorporated places

- Ashley

- Driftwood

- Ingersoll

- Nescatunga

- Yewed

NRHP sites

The following sites in Alfalfa County are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

|

|

References

- "Alfalfa County, Oklahoma". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Dianna Everett, "Alfalfa County," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed January 19, 2016.

- Shirk, George H. (March 15, 1987). Oklahoma Place Names (Revised ed.). University of Oklahoma Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0806120287.

- Burl E. Self, "Black Dog (1780-1848)", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed November 5, 2009

- "Full text of "Wah Kon Tah The Osage And White Man S Road"". Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, "History of the Great Salt Plains Lake" Accessed June 22, 2016

- Louis F. Burns, "Osage", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed November 5, 2009

- "ORIGIN OF COUNTY NAMES IN OKLAHOMA, Vol. 2, No. 1, March 1924". Oklahoma Historical Society's Chronicles of Oklahoma. Oklahoma State University. p. 75. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Bergen, JW. "Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online - Alfalfa County (Oklahoma, USA)". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. GAMEO. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- "Oklahoma Winter Wheat County Estimates" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Service - Southern Plains Regional Field Office. United States Department of Agriculture. December 11, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "Oklahoma Grain Sorghum County Estimates" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Service - Southern Plains Regional Field Office. United States Department of Agriculture. March 2, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Lawter, Jason (2012). "STATISTICAL DEPARTMENT 2012" (PDF). www.occeweb.com. OKLAHOMA CORPORATION COMMISSION - OIL AND GAS CONSERVATION DIVISION. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Wertz, Joe (December 14, 2012). "Map: Where Natural Gas is Produced in Oklahoma". Oklahoma - Economy, Energy, Natural Resources: Policy to People. StateImpact. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Wertz, Joe (December 7, 2012). "Map: Where Oklahoma Oil is Produced". Oklahoma - Economy, Energy, Natural Resources: Policy to People. StateImpact. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, "Welcome to Great Salt Plains Lake." Accessed May 12, 2016

- General Highway Map - Alfalfa County, Oklahoma (PDF) (Map) (1992 ed.). Oklahoma Department of Transportation, Planning Division.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- "Dr. R. Orin Cornett Biography". NCSA. National Cued Speech Association™. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- "Department of Physics History". University of Texas Physics History. University of Texas. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- "Kimbrough Named To INS All America Team". Port Arthur News. November 24, 1939.

- "Beryl Clark". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- "Norman Library literary landmark ceremony honors Harold Keith". The Norman Transcript. May 1, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "Hall of Fame Members-Harold Keith". Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- "3 Oklahomans To Be Inducted Into Sports Hall". NewsOK.com. October 14, 1987.

- Goldstein, Richard (October 4, 2007). "Wally Parks, Drag Racing Pioneer, Dies at 94". The New York Times.

- "Oklahoma Registration Statistics by County" (PDF). OK.gov. November 1, 2019. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 28, 2018.