Aging of Japan

Japan has the highest proportion of elderly citizens of any country in the world.[1] The country is experiencing a "super-aging" society both in rural and urban areas.[2] According to 2014 estimates, 33.0% of the Japanese population is above the age of 60, 25.9% are aged 65 or above, and 12.5% are aged 75 or above.[3] People aged 65 and older in Japan make up a quarter of its total population, estimated to reach a third by 2050.[4]

Japan had a post-war baby boom between 1947 and 1949. In 1948, Japan legalized abortion under special circumstances. The Eugenic Protection Law of 1948 allowed the involuntary sterilization of babies with intellectual disabilities until the law was overturned in 1996.

This was followed by a prolonged period of low fertility, resulting in the aging population of Japan.[5] The dramatic aging of Japanese society as a result of sub-replacement fertility rates and high life expectancy is expected to continue. Japan's population began to decline in 2011.[6] In 2014, Japan's population was estimated at 127 million; this figure is expected to shrink to 107 million (16%) by 2040 and to 97 million (24%) by 2050 should the current demographic trend continue.[7]

Japanese citizens largely view Japan as comfortable and modern, resulting in no sense of a population crisis.[6] The government of Japan has responded to concerns about the stress that demographic changes place on the economy and social services with policies intended to restore the fertility rate and make the elderly more active in society.[8]

Aging dynamics

In 1950, Japan's population of people over 65 years or older was only 4.9%. However, the rate increased to 11.7% in 1990.[9]

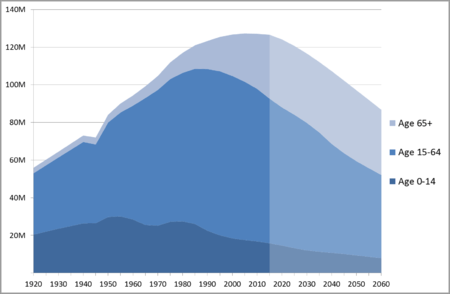

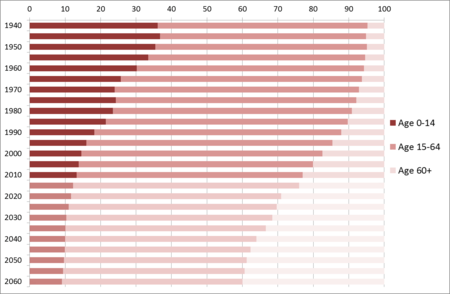

The number of Japanese people with ages 65 years or older nearly quadrupled in the last forty years, to 33 million in 2014, accounting for 26% of Japan's population. In the same period, the number of children (aged 14 and younger) decreased from 24.3% of the population in 1975 to 12.8% in 2014.[3] The number of elderly people surpassed the number of children in 1997, and sales of adult diapers surpassed diapers for babies in 2014.[10] This change in the demographic makeup of Japanese society, referred to as population ageing (kōreikashakai, 高齢化社会),[11] has taken place in a shorter span of time than in any other country.

According to projections of the population with the current fertility rate, over 65s will account for 40% of the population by 2060,[12][13] and the total population will fall by a third from 128 million in 2010 to 87 million in 2060.[14] Economists at Tohoku University established a countdown to national extinction, which estimates that Japan will have only one remaining child in 4205.[15] These predictions prompted a pledge by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe to halt population decline at 100 million.[8][10]

Causes

The aging of the Japanese population is a result of one of the world's lowest fertility rates combined with the highest life expectancy.

High life expectancy

Japan's life expectancy in 2016 was 85 years.[17] The life expectancy is 81.7 for males and 88.5 for females.[18] Since Japan's overall population is shrinking due to low fertility rates, the aging population is rapidly increasing.[19]

Factors such as improved nutrition, advanced medical and pharmacological technologies reduced the prevalence of diseases, improving living conditions. Moreover, peace and prosperity following World War II was integral to the massive economic growth of post-war Japan, leading to longer lifespans.[19] Proportion of health care spending has dramatically increased as Japan's older population spends time in hospitals and visits physicians. 2.9% people aged 75–79 were in a hospital and 13.4% visited physicians on any given day in 2011.[20]

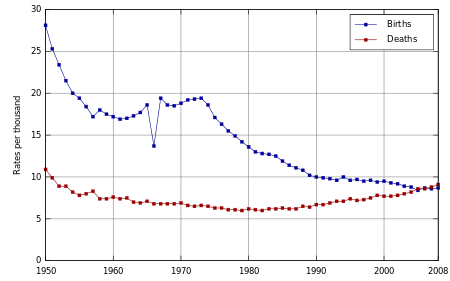

Life expectancy at birth has increased rapidly from the end of World War II, when the average was 54 years for women and 50 for men, as a result of improvements in medicine and nutrition, and the percentage of the population aged 65 years and older has increased steadily from the 1950s. The advancement of life expectancy translated into a depressed mortality rate until the 1980s, but mortality has increased again to 10.1 per 1000 people in 2013, the highest since 1950.[3]

Low fertility rate

Japan's total fertility rate (the number of children born to each woman in her lifetime) has been below the replacement threshold of 2.1 since 1974 and reached a historic low of 1.26 in 2005.[3] Experts believe that signs of a slight recovery reflect the expiration of a "tempo effect," as fertility rates accommodate a major shift in the timing and number of children, rather than any positive change.[22] As of 2016, the TFR was 1.41 children born/woman.[18]

Economy and culture

A range of economic and cultural factors contributed to the decline in childbirth during the late 20th century: later and fewer marriages, higher education, urbanization, increase in nuclear family households (rather than extended family), poor work–life balance, increased participation of women in the workforce, a decline in wages and lifetime employment along with a high gender pay gap, small living spaces, and the high cost of raising a child.[23][24][25][26]

Many young people face economic insecurity due to a lack of regular employment. About 40% of Japan's labor force is non-regular, including part-time and temporary workers.[27] Non-regular employees earn about 53 percent less than regular ones on a comparable monthly basis, according to the Labor Ministry.[28] Young men in this group are less likely to consider marriage or to be married.[29][30]

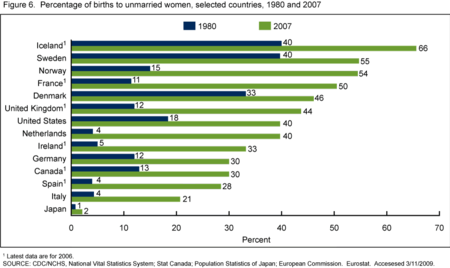

Although most married couples have two or more children,[31] a growing number of young people postpone or entirely reject marriage and parenthood. Conservative gender roles often mean that women are expected to stay home with the children, rather than work.[32] Between 1980 and 2010, the percentage of the population who had never married increased from 22% to almost 30%, even as the population continued to age,[3] and by 2035 one in four men will not marry during their prime parenthood years.[33] The Japanese sociologist Masahiro Yamada coined the term parasite singles (パラサイトシングル, parasaito shinguru) for unmarried women in their late 20s and 30s who continue to live with their parents.[34]

Fatigue and overworked

Yoshoku Sake Co. conducted a survey among working women between 20 and 39 years old in Japan in 2017. More than 60% of women answered that they cannot relax (over-tension, fatigue). They are not interested in wasting time to pursue love relationships (Japanese: renai) that lead to nowhere. The amount of work and responsibility has increased over the years while their physical strength declines with age. Women answered the cause of fatigue in the poll as: 1. Human relations of work (50.2%), 2. Content of work (44.5%), 3. Temperature and humidity (35.2%), 4. Work hours, overtime work and other workloads (30.8%), 5. Financial circumstances, financial unrest (27.2%). The survey by Yoshoku Sake Co. found that nearly 60% of people suffer from 1. chronic fatigue or 2. feel tired to love because of the feeling was or got cold or 3. the lover or family get irritated by little things.[35]

Women have joined the scores of overworked male employees and are too tired for dating. When women do have enough energy to go on a date, 1 in 4 women said they fell asleep during the date. Still 80% of the female respondents said they want a husband to settle down. They find stability (Japanese: antei) more important than showing off with a wedding. Increasing numbers of women use matchmaking (Japanese: konkatsu) to find a husband. Meanwhile, men are not interested in marriage, but 80% want a girlfriend. Men are reluctant to marry, because it would add complications, baggage to their lives and reduce their disposable income. In the 1980s, 60% to 70% of young people in their 20s were in a relationship. In 2017, young people (in their 20s) in a relationship had become part of the minority.[36]

Virginity rates

In 2015, 1 in 10 Japanese adults in their 30s were virgins and had no heterosexual sex experience. Women with heterosexual inexperience from 18 to 39 years old was 21.7 percent in 1992 and increased to 24.6 percent in 2015. Men with heterosexual inexperience from 18 to 39 years old was 20 percent in 1992 and increased to 25.8 percent in 2015. Men with stable jobs and a high income are more likely to have sex. Low income men are 10 to 20 times more likely to have no heterosexual sex experience. Women with lower income are more likely to have had intercourse. This is according to the National Fertility Survey of Japan by the Japanese National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.[37] Men who are unemployed are 8 times more likely to be virgins and men who are part-time or temporary employed have a 4 times higher virginity rate. This means that money and social status are important for men in the dating market.[38]

Herbivore men

There is a phenomenon of Herbivore men (Japanese: Sōshoku-kei danshi). These men are not interested in getting married or having a girlfriend. A 2010 survey with single men found that 61% of men in their 20s and 70% of men in their 30s call themselves herbivores.[39] However, the term "herbivorous men" carry quite a broad meaning-- it does not only mean men who do not pursue romantic interest, but could also imply men who do not conform to the traditional characteristics of a man; men who are gentle, kind and lack romantic assertiveness.

Effects

Demographic trends are altering relations within and across generations, creating new government responsibilities and changing many aspects of Japanese social life. The aging and decline of the working-age population has triggered concerns about the future of the nation's workforce, the potential for economic growth, and the solvency of the national pension and healthcare services.[40]

Social

A smaller population could make the country's crowded metropolitan areas more livable, and the stagnation of economic output might still benefit a shrinking workforce. However, the low birthrate and high life expectancy has also inverted the standard population pyramid, forcing a narrowing base of young people to provide and care for a bulging older cohort even as they try to form families of their own.[41] In 2014, the aged dependency ratio (the ratio of people over 65 to those age 15–65, indicating the ratio of the dependent elderly population to those of working age) was 40%, meaning two aged dependents for every five workers.[3] This is expected to increase to 60% by 2036 and to nearly 80% by 2060.[42]

Elderly Japanese have traditionally commended themselves to the care of their adult children, and government policies still encourage the creation of sansedai kazoku (三世代家族, "three-generation households"), where a married couple cares for both children and parents. In 2015, 177,600 people between the ages of 15 and 29 were caring directly for an older family member.[43] However, the migration of young people into Japan's major cities, the entrance of women into the workforce, and the increasing cost of care for both young and old dependents have required new solutions, including nursing homes, adult daycare centers, and home health programs.[44] Every year Japan closes 400 primary and secondary schools, converting some of them to care centers for the elderly.[45]

There are special nursing homes in Japan that offer service and assistance to more than 30 residents. In 2008, it has been recorded that there were approximate 6,000 special nursing homes available that cared for 420,000 Japanese elders.[46] With many nursing homes in Japan, the demand for more caregivers is high. In Japan, Family caregivers are preferred as the main caregiver, because it is a better support system if an elderly person is related to his/her caregiver. Therefore, it is possible that Japanese elderly people can perform activities of daily living (ADLs) with little assistance and live longer if his/her caregiver is a family caregiver.[46]

Many elderly people live alone and isolated, and every year thousands of deaths go unnoticed for days or even weeks, in a modern phenomenon known as kodoku-shi (孤独死, "solitary death").[47]

The disposable income in Japan's older population has increased business in biomedical technologies research in cosmetics and regenerative medicine.[5]

Political

The Greater Tokyo Area is virtually the only locality in Japan to see population growth, mostly due to internal migration from other parts of the country. Between 2005 and 2010, 36 of Japan's 47 prefectures shrank by as much as 5%,[3] and many rural and suburban areas are struggling with an epidemic of abandoned homes (8 million across Japan).[48][49] Masuda Hiroya, a former Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications who heads the private think tank Japan Policy Council, estimated that about half the municipalities in Japan could disappear between now and 2040 as young people, especially young women, move from rural areas into Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya, where around half of Japan's population is already concentrated.[50] The government is establishing a regional revitalization task force and focusing on developing regional hub cities, especially Sapporo, Sendai, Hiroshima, and Fukuoka.[51]

Internal migration and population decline have created a severe regional imbalance in electoral power, where the weight of a single vote depends on where it was cast. Some depopulated districts send three times as many representatives per voter to the National Diet as their growing urban counterparts. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Japan declared the disparities in voting power violate the Constitution, but the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which relies on rural and older voters, has been slow to make the necessary realignment.[41][52][53]

The increasing proportion of elderly people has a major impact on government spending and policies. As recently as the early- 1970s, the cost of public pensions, health care and welfare services for the aged amounted to only about 6% of Japan's national income. In 1992 that portion of the national budget was 18%, and it is expected that by 2025 28% of national income will be spent on social welfare.[54] Because the incidence of chronic disease increases with age, the health care and pension systems are expected to come under severe strain. In the mid- 1980s the government began to reevaluate the relative burdens of government and the private sector in health care and pensions, and it established policies to control government costs in these programs.[55]

The large share of elderly inflation averse voters may also hinder the political attractiveness of pursuing higher inflation consistent with the evidence that ageing may lead to lower inflation.[55] With the increasing older population and decreasing young population, 38% percent of the population will be people aged 65 and older by 2065. This concludes that Japan has the highest amount of public debt in the world because of the low fertility rates and aging population.[56] Japan's government has spent almost half of its tax revenue trying to recover from their debt. According to IMF, Japan has a 246.14 debt percentage of GDP making it the highest public debt.[57]

Economic

.png)

Since the 1980s, there has been an increase of older-age workers and a shortage of young workers in Japan's workforce, from employment practices to benefits to the participation of women. The U.S. Census Bureau estimated in 2002 that Japan would experience an 18% decrease of young workers in its workforce and 8% decrease in its consumer population by 2030. The Japanese labor market is already under pressure to meet demands for workers, with 125 jobs for every 100 job seekers at the end of 2015, as older generations retire and younger generations become smaller in quantity.[58]

Japan made a radical change in how its healthcare system is regulated by introducing long-term care insurance in 2000.[5] The proportion of old Japanese citizens will soon level off, however; there is a decline in young population due to zero growth, death exceeding the births. For example, number of young people under the age of 19 in Japan will constitute only 13 percent in the year 2060, which used to be 40 percent in 1960.[5]

Japan's aging population is considered economically prosperous profiting the large corporations. Lawson Inc., a Japanese convenience store chain has salons for senior citizens that feature adult wipes and diapers, strong detergents to eliminate urine on bed mats, straw cups, gargling basins, and rice and water.[5] The decline in the working population is impacting the national economy. It is causing a shrinkage of the nation's military.[5] The government has focused on medical technologies such as regenerative medicines and cell therapy to recruit and retain more older population into the work force.[5] A range of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have also pioneered new practices for retaining workers beyond mandated retirement ages, such as through workplace improvements to create working environments better suited to older workers as well as new job tasks specifically for older workers.[59]

Mounting labor shortages in the 1980s and 90s led many Japanese companies to increase the mandatory retirement age from 55 to 60 or 65, and today many allow their employees to continue working after official retirement. The growing number of retirement age people has put strain on the national pension system. In 1986, the government increased the age at which pension benefits begin from 60 to 65, and shortfalls in the pension system have encouraged many people of retirement age to remain in the workforce and have driven some others into poverty.[54]

The retirement age may go even higher in the future if Japan continues to have older age populations in its overall population. A study by the UN Population Division released in 2000 found that Japan would need to raise its retirement age to 77 (or allow net immigration of 17 million by 2050) to maintain its worker-to-retiree ratio.[60][61] Consistent immigration into Japan may prevent further population decline, therefore, it is encouraged that Japan develops policies that will support large influx of young immigrants.[62][6]

Less desirable industries, such as agriculture and construction, are more threatened than others. The average farmer in Japan is 70 years old,[63] and while about a third of construction workers are 55 or older, including many who expect to retire within the next ten years, only one in ten are younger than 30.[64][65]

The decline in working-aged cohorts may lead to a shrinking economy if productivity does not increase faster than the rate of Japan's decreasing workforce.[66] The OECD estimates that similar labor shortages in Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Sweden will depress the European Union's economic growth by 0.4 percentage points annually from 2000 to 2025, after which shortages will cost the EU 0.9 percentage points in growth. In Japan labor shortages will lower growth by 0.7 percentage points annually until 2025, after which Japan will also experience a 0.9 percentage points loss in growth.[67]

Places with high birthrates

These are places in Japan with significant higher birthrates than the national average:

Nagareyama

The city Nagareyama in Chiba Prefecture is 30 kilometers from Tokyo. Most Japanese cities have a shortage of daycare centers and no transit services for children. In early 2000, Nagareyama had an exodus of young people. Men and women are usually occupied with jobs during daytime. However, Nagareyama lets women pursue their career while their children spend time in childcare facilities. In 2003, mayor Yoshiharu Izaki made investments in childcare centers a primary focus of the city's government. It includes a transit service at Nagareyama-centralpark Station where parents can drop off their children on their way to work. The children are shuttled with buses to daycare centers. Senior people of the local community help with shuttling the children. Many parents say this transit service was one of the biggest reasons for them to move to Nagareyama. The result is over the past 13 years (2006-2019) the population has grown by more than 20%. 85% of children have more than one sibling. Young children are expected to outnumber elderly in the future. Parents worry less about having more children, because the whole community helps with raising children and parents don't feel isolated. People in Nagareyama have a strong local network, with a friendly neighborhood. People share information and concerns. There are also many local events and community spaces where children and elderly interact. There's a summer camp for children while their parents work during holidays. These family friendly approaches lured young working parents from Tokyo to Nagareyama.[68]

Okinawa Prefecture

Okinawa prefecture has the highest birthrate in Japan for more than 40 years since recording began in 1899. Okinawa was the only prefecture with a natural population increase compared to the rest of Japan in 2018. The fertility rate was 1.89 while Tokyo had the lowest of 1.20 and the national average was 1.42 in 2018.[69] There were 15,732 births and 12,157 deaths according to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The average age of marriage is lower in Okinawa at 30 years for men and 28.8 years for women. The national average is 31.1 years for men and 29.4 years for women.[70]

Anthropologist Dr. Thang Leng Leng (National University of Singapore) said families tend to have more than two children because of “Okinawa’s sense of social norms, in terms of ‘this is how things should be’,”. It's considered normal to marry and then have children. This is despite Okinawa having less welfare for children compared to other regions in Japan. It's not unusual for women in their 40s to have children. 1 in 20 babies born at the Nanbu Tokushukai Hospital are conceived via IVF. Living in Okinawa is less stressful due to lower incomes and lower living costs. Raising a child is less expensive and fewer students attend university in Okinawa. Dr. Thang said people in Okinawa are more relaxed with a tropical culture and not so punctual as the rest of Japan. Working in Okinawa is more laid back. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's workplace policies enable returning mothers to work more flexible and leave work earlier. There's less competition in the workplace due to less high paying large corporations compared to Osaka and Tokyo. Pediatrician, Chuken Miyagi said there's a culture of mutual help and support called yuimaru. Grandparents and relatives live relatively close to help family members and mothers with raising their children. There's a high sense of closeness among the people of Okinawa, because society is largely rural with more living space. In big cities like Tokyo, people frequently rent houses and live there temporarily which hampers the development of close bonds with the neighborhood and local people. Okinawa has increasing numbers of ikumen; fathers who are actively involved in child-rearing. The ratio of mothers to fathers at the Jinen Pediatric Clinic in Okinawa is 7 to 3 compared to 10 to 0 in mainland Japan (2018).[70]

Government policies

The Japanese government is addressing demographic problems by developing policies to encourage fertility and keep more of its population, especially women and elderly, engaged in the workforce.[71] Incentives for family formation include expanded opportunities for childcare, new benefits for those who have children, and a state-sponsored dating service.[72][73] Some policies have focused on engaging more women in the workplace, including longer maternity leave and legal protections against pregnancy discrimination, known in Japan as matahara (マタハラ, maternity harassment).[71][74] However, "Womenomics," the set of policies intended to bring more women into the workplace as part of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's economic recovery plan, has struggled to overcome cultural barriers and entrenched stereotypes.[75]

These policies could prove useful for bringing women back into the workforce after having children, but they can also encourage the women who opt not to have children to join the workforce. The Japanese government has introduced other policies to address the growing elderly population as well, especially in rural areas. Many young people end up moving to the city in search of work, leaving behind a growing elderly population and a smaller work force to take care of them. Because of this, Japan's national government has tried to improve welfare services such as long-term care facilities and other services that can help families at home such as day-care or in-home nursing assistance. The Gold Plan was introduced in 1990 to improve these services and attempted to reduce the burden of care placed on families, followed by long-term care insurance (LTCI) in 2000.[76] These plans have been upgraded and revised over the years to provide more local welfare services and institutions in rural areas, yet the rapidly increasing elderly population makes these efforts difficult to maintain.

Immigration

A net decline in population due to a historically low birth rate has raised the issue of immigration, as a way to compensate for labor shortages.[77][78] While public opinion polls tend to show low support for immigration, most people support an expansion in working-age migrants on a temporary basis to maintain Japan's economic status.[79][80] Comparative reviews show that Japanese attitudes are broadly neutral and place Japanese acceptance of migrants in the middle of developed countries.[81][82]

Immigrants would have to increase by eight percent in order for Japan's economy to be stable. Japan's government is first trying to increase tourism rates which increases their economy and brings in foreign workers. The government has also recruited international students which allow foreigners to begin work and potentially stay in Japan to help the economy. However, Japan is strict when accepting refugees into their country. Only 27 people out of 7,500 refugee applicants were granted into Japan in 2015. Though, Japan provides high levels of foreign and humanitarian aid.[83] In 2016, there was a 44% increase in asylum seekers to Japan from Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines. Since Japan did not desire low-skilled workers to enter, many people went through the asylum route instead. This allowed immigrants to apply for the asylum and begin work six months after the application. However, it did not allow foreigners without valid visas to apply for work.[77]

Work-life balance

Japan has focused its policies on the work-life balance with the goal of improving the conditions for increasing the birth rate. To address these challenges, Japan has established goals to define the ideal work-life balance that would provide the environment for couples to have more children with the passing of the Child Care and Family Care Leave Law, which took effect in June 2010.[84]

The law provides both mothers and fathers with an opportunity to take up to one year of leave after the birth of a child (with possibility to extend the leave for another 6 months if the child is not accepted to enter nursery school) and allows employees with preschool-age children the following allowances: up to five days of leave in the event of a child's injury or sickness, limits on the amount of overtime in excess of 24 hours per month based on an employee's request, limits on working late at night based on an employee's request, and opportunity for shorter working hours and flex time for employees.[85]

The goals of the law would strive to achieve the following results in 10 years are categorized by the female employment rate (increase from 65% to 72%), percentage of employees working 60 hours or more per week (decrease from 11% to 6%), rate of use of annual paid leave (increase from 47% to 100%), rate of child care leave (increase from 72% to 80% for females and .6% to 10% for men), and hours spent by men on child care and housework in households with a child under six years of age (increase from 1 hour to 2.5 hours a day).[84]

Comparisons with other countries

Japan's population is aging faster than any other country on the planet.[86] The population of those 65 years or older roughly doubled in 24 years, from 7.1% of the population in 1970 to 14.1% in 1994. The same increase took 61 years in Italy, 85 years in Sweden, and 115 years in France.[87] Life expectancy for women in Japan is 87 years, five years more than that of the U.S.[88] Men in Japan with a life expectancy of 81 years, have surpassed U.S. life expectancy by four years.[88] Japan also has more centenarians than any other country (58,820 in 2014, or 42.76 per 100,000 people). Almost one in five of the world's centenarians live in Japan, and 87% of them are women.[89]

In contrast to Japan, a more open immigration policy has allowed Australia, Canada, and the United States to grow their workforce despite low fertility rates.[67] An expansion of immigration is often rejected as a solution to population decline by Japan's political leaders and people. Reasons include a fear of foreign crime, a desire to preserve cultural traditions, and a belief in the ethnic and racial homogeneity of the Japanese nation.[90]

Historically, European countries have had the largest elderly populations by proportion as they became developed nations earlier and experienced the subsequent drop in fertility rates, but many Asian and Latin American countries are quickly catching up. As of 2015, 22 of the 25 oldest countries are located in Europe, but Japan is currently the oldest country in the world and its rapidly aging population displays a trend that other parts of Asia such as South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are expected to follow by 2050.[91] As recently developed nations continue to experience improved health care and lower fertility rates, the growth of the elderly population will continue to rise. In 1970–1975, only 19 countries had a fertility rate that can be considered below-replacement fertility and there were not any countries with exceedingly low fertility (<1.3 children); however, between 2000–2005, there were 65 countries with below-replacement fertility and 17 with exceedingly low fertility.[92]

While there has been a global trend of lower fertility and longer life expectancy, it is first evident in the more developed countries and occurs more rapidly in developing or recently developed countries. One of the most astounding aspects of Japan's elderly population, in particular, is that it is both fast-growing and has one of the highest life expectancies equating to a larger elderly population and an older one. According to the World Health Organization, Japanese people are able to live 75 years without any disabilities and fully healthy compared to other countries. Also, American women usually live to around 81 years and American men 76; but compared to Japan, women live to around 87 years and men to 80 years.[93] There is demographic data that shows Japan is an older and more quickly aging society than United States.[94] Japan, also, has reached the condition aging much faster than other developed countries, and they have the highest life expectancy rate among developed countries. They, also, have the highest proportion of the elderly population as well with the highest population decline of developed countries.

Japan is leading the world in aging demographics, but the other countries of East Asia are following a similar trend. In South Korea, where the fertility rate often ranks among the lowest in the OECD (1.21 in 2014), the population is expected to peak in 2030.[95] The smaller states of Singapore and Taiwan are also struggling to boost fertility rates from record lows and to manage aging populations. More than a third of the world's elderly (65 and older) live in East Asia and the Pacific, and many of the economic concerns raised first in Japan can be projected to the rest of the region.[96][97] India's population is aging exactly like Japan, but with a 50-year lag. A study of the populations of India and Japan for the years 1950 to 2015 combined with median variant population estimates for the years 2016 to 2100 shows that India is 50 years behind Japan on the aging process.[98]

See also

- Children's Day (Japan)

- Demographics of Japan

- Elderly people in Japan

- Marriage in Japan

- Respect for the Aged Day

General:

- List of countries and dependencies by population

- List of countries and dependencies by population density

- Generational accounting

- Sub-replacement fertility

International:

- Aging of Europe

- Aging in the American workforce

- Russian Cross

References

- "Elderly citizens accounted for record 28.4% of Japan's population in 2018, data show". The Japan Times. 15 September 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Muramatsu, Naoko (August 1, 2011). "Japan: Super-Ageing Society Preparing for the Future". The Gerontologist. 51 (4): 425–432. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr067. PMID 21804114.

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, Statistics Bureau. "Japan Statistical Yearbook, Chapter 2: Population and Households". Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "Aging in Japan|ILC-Japan". www.ilcjapan.org. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- "Bold steps: Japan's remedy for a rapidly aging society". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- Armstrong, Shiro (May 16, 2016). "Japan's Greatest Challenge (And It's Not China): Massive Population Decline". The National Interest. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Johnston, Eric (16 May 2015). "Is Japan becoming extinct?". The Japan Times Online. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Yoshida, Reiji (29 October 2015). "Abe convenes panel to tackle low birthrate, aging population". The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Martin, Linda G. "Japan's Golden Plan". 1993 Britannica Medical and Health Annual: 337.

- "Fighting Population Decline, Japan Aims to Stay at 100 Million". Nippon.com. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Traphagan, John W. (2003). Demographic Change and the Family in Japan's Aging Society. Suny Series in Japan in Transition, SUNY Series in Aging and Culture, Suny Series in Japan in Transition and Suny Series in Aging and Culture. SUNY Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0791456491.

- "Japan population to shrink by a third by 2060". The Guardian. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- International Futures. "Population of Japan, Aged 65 and older". Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- Population Projections for Japan (January 2012): 2011 to 2060, table 1-1 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, retrieved 13 January 2016).

- Yoshida, Hiroshi; Ishigaki, Masahiro. "Web Clock of Child Population in Japan". Mail Research Group, Graduate School of Economics and Management, Tohoku University. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- Clyde Haberman (1987-01-15). "Japan's Zodiac: '66 was a very odd year". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency".

- "East Asia/Southeast Asia :: Japan — the World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency".

- "Population Aging and Aged Society: Population Aging and Life Expectancy" (PDF). International Longevity Center Japan. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- "Health Status: Utilization of Health Care" (PDF). International Longevity Center Japan. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- "Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States". CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. May 13, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- Harding, Robin (4 February 2016). "Japan birth rate recovery questioned". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. "Statistical Handbook of Japan 2014". Chapter 5. Retrieved 18 January 2016.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Yamada, Masahiro (3 August 2012). "Japan's Deepening Social Divides: Last Days for the "Parasite Singles"". Nippon.com. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Why the Japanese are having so few babies". The Economist. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- http://www.demogr.mpg.de/papers/working/wp-2013-004.pdf

- "1 in 4 men, 1 in 7 women in Japan still unmarried at age 50: Report". The Japan Times Online. 2017-04-05.

- Nohara, Yoshiaki (1 May 2017). "Japan Labor Shortage Prompts Shift to Hiring Permanent Workers". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- IPSS, "Attitudes toward Marriage and Family among Japanese Singles" (2011), p. 4.

- Hoenig, Henry; Obe, Mitsuru (8 April 2016). "Why Japan's Economy Is Laboring". Wall Street Journal.

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS). "Marriage Process and Fertility of Japanese Married Couples." (2011). pp. 9–14.

- Soble, Jonathan (January 1, 2015). "The New York Times". Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Yoshida, Reiji (31 December 2015). "Japan's population dilemma, in a single-occupancy nutshell". The Japan Times. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Wiseman, Paul (2 June 2004). "No sex please we're Japanese". USA Today. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- Ishimura, Sawako (October 24, 2017). "お疲れ女子の6割は恋愛したくない!?「疲労の原因」2位は仕事内容、1位は?(60% of tired women do not want to love!? "Cause of fatigue" second place work content, first place?)". Cocoloni Inc. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Shoji, Kaori (December 2, 2017). "Women in Japan too tired to care about dating or searching for a partner". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Shibuya, Kenji (8 April 2019). "First national estimates of virginity rates in Japan". The University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- Shibuya, Kenji (8 April 2019). "Let's Talk About (No) Sex: A Closer Look at Japan's 'Virginity Crisis'". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Harney, Alexandra. "Japan panics about the rise of "herbivores"—young men who shun sex, don't spend money, and like taking walks. - Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Hashimoto, Ryutaro (attributed). General Principles Concerning Measures for the Aging Society. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved 2011-3-5.

- Soble, Jonathan (26 February 2016). "Japan Lost Nearly a Million People in 5 Years, Census Says". New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Population Projections for Japan (January 2012): 2011 to 2060, table 1-4 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, retrieved 13 January 2016).

- Oi, Mariko (16 March 2015). "Who will look after Japan's elderly?". BBC. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Kelly, William. "Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Transpositions of Everyday Life." Ed. Andrew Gordon. Postwar Japan as History. University of California Press, 1993. pp. 208–10.

- McNeill, David (2 December 2015). "Falling Japanese population puts focus on low birth rate". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Olivares-Tirado, Pedro (2014). Trends and Factors in Japan's Long-term Care Insurance System: Japan's 10-year Experience. Springer. pp. 80–130. ISBN 978-94-007-7874-0.

- Bremner, Matthew (26 June 2015). "The Lonely End". Slate. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Otake, Tomoko (7 January 2014). "Abandoned homes a growing menace". The Japan Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Soble, Jonathan (23 August 2015). "A Sprawl of Ghost Homes in Aging Tokyo Suburbs". New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Tadashi, Hitora (25 August 2014). "Slowing the Population Drain From Japan's Regions". Nippon.com. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- "Abe to target revitalization at regional level". The Japan Times. Jiji. 21 July 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Masunaga, Hidetoshi (12 December 2013). "The Quest for Voting Equality in Japan". Nippon.com. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Takenaka, Harukata (30 July 2015). "Weighing Vote Disparity in Japan's Upper House". Nippon.com. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Faiola, Anthony (28 July 2006). "The Face of Poverty Ages In Rapidly Graying Japan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Vlandas, T (2018). "Grey power and the economy: Ageing and inflation across advanced economies" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies. 51 (4): 514–552. doi:10.1177/0010414017710261.

- "Japan's population set to plummet by 40 million in a generation". The Independent. 2017-04-11. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- "The 20 countries with the greatest public debt". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- Warnock, Eleanor (24 December 2015). "Japan consumer prices up, but spending sluggish". Market Watch. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Martine, Julien; Jaussaud, Jacques (2018). "Prolonging working life in Japan: Issues and practices for elderly employment in an aging society". Contemporary Japan. 30 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/18692729.2018.1504530.

- Unknown (2000). "Aging Populations in Europe, Japan, Korea, Require Action". India Times. Archived from the original on 2007-12-01. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- Schlesinger, Jacob M. (2015). "Aging Gracefully: entrepreneurs and exploring robotics and other innovations to unleash the potential of the elderly". WSJ: 1–15.

- Harding, Robin (21 February 2016). "Japan seeks to bank on global appetite for sushi and wagyu beef". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Builders face lack of young workers". The Japan Times. Kyodo. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Takami, Kosuke; Wamoto, Takako; Itsuki, Kotaro (22 February 2014). "Young laborer shortage growing dire on Japan's construction sites".

- “Into the Unknown.” The Economist, http://search.proquest.com/docview/807974249

- Paul S. Hewitt (2002). "Depopulation and Ageing in Europe and Japan: The Hazardous Transition to a Labor Shortage Economy". International Politics and Society. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- "Japan Baby Boom: City's policies turn around population decline". TRT World. 2019-09-14. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) - Number of newborns in Japan fell to record low while population dropped faster than ever in 2018

- Elizabeth Lee (2019-12-21). "Fertility secrets of Okinawa give birth to hope in sexless, ageing Japan". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- "Urgent Policies to Realize a Society in Which All Citizens are Dynamically Engaged" (PDF). Kantei (Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet). Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- "Young Japanese 'decline to fall in love'". BBC News. 2012-01-11.

- Ghosh, Palash (21 March 2014). "Japan Encourages Young People To Date And Mate To Reverse Birth Rate Plunge, But It May Be Too Late". International Business Times. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Rodionova, Zlata (16 November 2015). "Half of Japanese women workers fall victim to 'maternity harassment' after pregnancy". The Independent. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Chen, Emily S. (6 October 2015). "When Womenomics Meets Reality". The Diplomat. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Tanaka, Kimiko; Iwasawa, Miho (October 2010). "Aging in Rural Japan—Limitations in the Current Social Care Policy". Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 22 (4): 394–406. doi:10.1080/08959420.2010.507651. ISSN 0895-9420. PMC 2951623. PMID 20924894.

- CNN; Jozuka, Emiko; Ogura; CNN Graphics by Natalie Leung. "Can Japan survive without immigrants?". CNN. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- Brasor, Philip (27 October 2018). "Proposed reform to Japan's immigration law causes concern". Japan Times. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "51% of Japanese support immigration, double from 2010 survey - AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Ajw.asahi.com. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- Facchini, G.; Margalit, Y.; Nakata, H. (2016), Countering Public Opposition to Immigration: The Impact of Information Campaigns (PDF), p. 19,

Our findings indicate that among the non-treated sample, only 29% of the population supported an increase in levels of immigration, a finding that is consistent with the restrictive immigration policy stance currently pursued by the Japanese government.

- Simon, Rita J.; Lynch, James P. (1999). "A Comparative Assessment of Public Opinion toward Immigrants and Immigration Policies". The International Migration Review. 33 (2): 455–467. doi:10.1177/019791839903300207. JSTOR 2547704.

- "New Index Shows Least, Most Accepting Countries for Migrants". Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- Green, David (2017-03-27). "As Its Population Ages, Japan Quietly Turns to Immigration". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Introduction to the Revised Child Care and Family Care Leave Law,” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html, accessed May 22, 2011.

- Japanese government's Employment Service Center “雇用継続給付” https://www.hellowork.go.jp/insurance/insurance_continue.html, Retrieved April 24, 2017

- "Japan's demography: The incredible shrinking country". The Economist. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Statistical Handbook of Japan". Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Jacob Schlesinger; Alexander Martin (November 29, 2015). "The Wall Street Journal". Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- "Centenarians in Japan: 50,000-Plus and Growing". Nippon.com. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Burgess, Chris (18 June 2014). "Japan's 'no immigration principle' looking as solid as ever". The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- He, Wan; Goodkind, Daniel; Kowal, Paul (March 2016). "An Aging World : 2015". International Population Reports. 16: 1–30.

- Naohiro Ogawa; Rikiya Matsukura (2007). "Ageing in Japan: The health and wealth of older persons" (PDF). un.org. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "Japan Has The Highest Life Expectancy Of Any Major Country. Why?". NBC News. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- Karasawa, Mayumi; Curhan, Katherine B.; Markus, Hazel Rose; Kitayama, Shinobu S.; Love, Gayle Dienberg; Radler, Barry T.; Ryff, Carol D. (2011). "Cultural Perspectives on Aging and Well-Being: A Comparison of Japan and the U.S." International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 73 (1): 73–98. doi:10.2190/AG.73.1.d. PMC 3183740. PMID 21922800.

- Kwanwoo, Jun (11 July 2014). "South Korea's Youth Population Slips Under 10 Million". Wall Street Journal (Korea Realtime blog). Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "Rapid Aging in East Asia and Pacific Will Shrink Workforce and Increase Public Spending". World Bank. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "The Future of Population in Asia: Asia's Aging Population" (PDF). East West Center. Honolulu: East-West Center. 2002. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "Is India Aging Like Japan? Visualizing Population Pyramids". SocialCops Blog. 2016-06-22. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

External links

- Japanese Statistics Bureau Statistical Yearbook

- Another Tsunami Warning: Caring for Japan's Elderly, (NBR Expert Brief, April 2011)