Aging in the American workforce

The aging workforce, controversially referred to as The Silver Tsunami,[1] refers to the rise in the median age of the United States workforce to levels unseen since the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935. It is projected that by the year 2020, about 25% of the U.S. workforce will be composed of older workers (ages 55 and over).[2] While many factors contribute to the aging workforce, the Post-World War II baby boom created an unusually large birth cohort for the U.S. population, resulting in a large aging population today. This phenomenon has many short-term and long-term implications, affecting many areas, including the U.S. economy, society and public health.

Baby boom

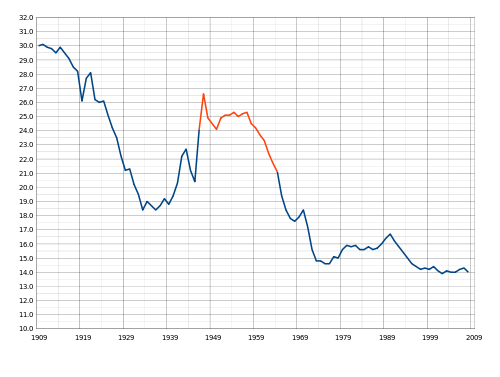

Starting in the years following World War II, from 1946 to 1964, about 76 million people were born in the United States, creating a large birth cohort known as the Baby boomers.[4][5]

Projections

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of April 2014, the labor force participation rate was 62.8%.[6] The overall labor force participation rate is expected to decline for the remainder of the decade, projected to fall to 62.5% in 2020.[7] By the year 2020, the subpopulation of older adults in the United States is expected to reach 97.8 million people, comprising 28.7% percent of the entire U.S. population, a rise from the 24.7% in 2010.[7] This increase in proportion of older adults can be attributed to the entire Baby Boomer cohort joining the older adult population (ages 55+) by 2020.

It is projected that by 2020, the proportion of the U.S. labor force that is composed of older adults will be 25.2%.[2][7] This continues a trend in increasing rates of older adults remaining in the workforce, as the rates were 13.1% in 2000 and 19.5% in 2010.[7] A complementary trend that follows this is the increasing median age of the U.S. workforce. By 2020, the workforce is expected to have a median age of 42.8, which will be an increase from 39.3 in 2000 and 41.7 in 2010.[8]

A further factor contributing to an aging workforce is the fact that employment rates among older workers are increasing. The rate of people who continue working after they are 65 is relatively high in the US, when compared to other developed countries. For example, in 2011, 16.7% among people aged 65 and over and 29.9% among 65–69 were employed in the US.

Impacts

With continuing trends of an aging American workforce and a declining labor force participation rate, there may be many consequences arising from this phenomenon. The impending repercussions from a large aging workforce entering retirement has led some to call this situation "The Silver Tsunami",[9][10][11] although this metaphorical phrase has been controversial due to its ageist connotations.[1]

Economy

Due to a declining labor participation rate, there is expected to be a shortage of workers in the U.S. workforce. Projections show that the demand for labor needed now is not being fulfilled, and the gap between labor needed and labor available will continue to expand over the future.[12][13] Owing to the differences in population size between the Baby Boomers and the following younger generations, there has been negative growth in the working age population.[12][13] The baby "busters", also known as generation X, are not as plentiful as the baby boomer generation. They are spending more time educating themselves and training and are entering the workforce at a later age. Therefore, there are fewer and fewer entering the workforce in their early twenties. Baby boomers retiring, means fewer working people and reduces productivity rates in the workforce. The workforce is also losing those skilled enough to do the jobs we have now. A loss in skilled and capable workers has made it harder for employers to recruit new staff.[14] The retirement of members of the aging workforce could possibly result in the shortage of skilled labor in the future.[2][4] A majority of experienced utility workers and hospital caregivers, for example, will be eligible for retirement.[4]

Social security benefits

The U.S. federal social security system functions through the taxation of large numbers of young workers, in order to support smaller numbers of older dependents.[4] A diminishing workforce, coupled with growing numbers of longer-living elderly can deplete the social security system. The Social Security Administration estimates that the old age dependency ratio (people ages 65+ divided by people ages 20–64) in 2080 will be over 40%, compared to the 20% old age dependency ratio in 2005.[4] Increasing life expectancies of the older population will not only result in decreases in Social Security Benefits, but also devalues private and public pension programs.[4][15] The death of funds supplying programs such as social security and Medicare may be a contributing factor for adults to delay retirement and to continue working.[16]

Occupational safety and health

Because of the many older adults opting to remain in the U.S. workforce, many studies have been done to investigate whether the older workers are at greater risk of occupational injury than their younger counterparts. Due to the physical declines associated with aging, older adults tend to exhibit losses in eyesight, hearing and physical strength.[4] Data shows that older adults have low overall injury rates compared to all age groups, but are more likely to suffer from fatal and more severe occupational injuries.[4][17] Of all fatal occupational injuries in 2005, older workers accounted for 26.4%, despite only comprising 16.4% of the workforce at the time.[17] Age increases in fatality rates in occupational injury are more pronounced for workers over the age of 65.[17] The return to work for older workers is also extended; older workers experience a greater median number of lost work days and longer recovery times than younger workers.[17] Some common occupational injuries and illnesses for older workers include arthritis[16] and fractures.[18] Among older workers, hip fractures are a large concern, given the severity of these injuries.[18]

Health care

With larger numbers of older adults, there will be an increased need for geriatric care. Older adults will have to deal with more chronic diseases; older adults who have worked in the construction industry have shown high rates of chronic diseases.[15][19] Experts suggest that the number of geriatricians will have to triple to meet the demands of the rising elderly.[9] There is expected to be a similarly increased demand in other healthcare professionals, such as nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists and dentists.[9] In addition, there is expected to be an increasing demand over common geriatric care consumption needs, such as medications, joint replacements and cardiovascular operations.[9]

Society

Population aging can potentially change American society as a whole. Many companies use an antiquated system, in which older, tenured workers get raises and benefits over time, eventually hitting retirement.[10] With larger numbers of older workers in the workforce, this model is possibly unsustainable. In addition, perceptions of older adults in society will change, as the elderly are living longer lives and more active than before. A University of Alabama at Birmingham article stated that society faces a cultural ageism in the perceptions about older adults, which will change over time.[9]

See also

- Baby boomer

- Demography

- Old age

- Post-World War II baby boom

- The Silver Tsunami (metaphor)

References

- Barusch, Amanda (2013). "The Aging Tsunami: Time for a New Metaphor?". Journal of Gerontological Social Work 56: 181–4.

- Chosewood, L. Casey (July 19, 2012). "CDC - NIOSH Science Blog - Safer and Healthier at Any Age: Strategies for an Aging Workforce". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- CDC Bottom of this page https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/vsus.htm "Vital Statistics of the United States, 2003, Volume I, Natality", Table 1-1 "Live births, birth rates, and fertility rates, by race: United States, 1909–2003."

- Silverstein, Michael (2008). "Meeting the challenges of an aging workforce". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 51 (4): 269–280. doi:10.1002/ajim.20569. PMID 18271000.

- Toossi, Mitra (November 2006). "A new look at long-term labor force projections to 2050". Monthly Labor Review. 129 (11): 19–39.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (July 26, 2012). "Bureau of Labor Statistics Data". Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- Toossi, Mitra (January 2012). "Labor force projections to 2020: a more slowly growing workforce". Monthly Labor Review. 135 (1): 43–64.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (February 1, 2012). "Median age of the labor force, by sex, race and ethnicity". Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- Bob Shepard, The University of Alabama at Birmingham (December 30, 2010). "Beware the "silver tsunami" - the boomers turn 65 in 2011". The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- The Economist (February 4, 2010). "Schumpeter: The silver tsunami". The Economist. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- Alliance for Aging Research (Summer 2006). "Alliance for Aging Research: Publications: Preparing for the Silver Tsunami". Alliance for Aging Research. Archived from the original on 2012-08-07. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- Howard, John (March 23, 2011), "The Future Workforce and Applied Ergonomics", 14th Annual Applied Ergonomics conference & Expo, Orlando, Florida

- Schill, Anita L. (May 18, 2011), The Future of Work & the Aging Workforce, Electricity Safety Summit, Washington, District of Columbia

- Woolley, Josephine (2006). Ageism in the Era of Workforce Shrinkage. Greenleaf Publishing (IngentaConnect). pp. 113–129. ISBN 9781909493605.

- Schwatka, Natalie V.; Butler, Lesley M.; Rosecrance, John R. (2012), "An aging workforce and injury in the construction industry", Epidemiologic Reviews, 34: 156–167, doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr020, PMID 22173940

- Caban-Martinez, Alberto J.; Lee, David J.; Fleming, Lora E.; Tancredi, Daniel J.; Arheart, Kristopher L.; LeBlanc, William G.; McCollister, Kathryn E.; Christ, Sharon L.; Louie, Grant H.; Muennig, Peter A. (2011), "Arthritis, occupational class, and the aging US workforce", American Journal of Public Health, 101 (9): 1729–1734, doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300173, PMC 3154222, PMID 21778483

- Grosch, James W.; Pransky, Glenn S. (2010), "Safety and Health Issues for an Aging Workforce", in Czaja, Sara J; Sharit, Joseph (eds.), Aging and Work: Issues and Implications in a Changing Landscape, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011), "Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses among older workers - United States, 2009", Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60 (16): 503–508, PMID 21527887

- Dong, Xiuwen S.; Wang, Xuanwen; Daw, Christina; Ringen, Knut (2011), "Chronic disease and functional limitations among older construction workers in the United States: a 10-year follow-up study", Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53 (4): 372–380, doi:10.1097/jom.0b013e3182122286, PMID 21407096