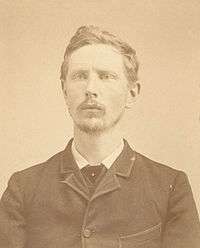

Adolph Fischer

Adolph Fischer (1858 – November 11, 1887) was an anarchist and labor union activist tried and executed after the Haymarket Riot.

Adolph Fischer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1858 |

| Died | November 11, 1887 (age 28-29) Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Occupation | Printer |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Conspiracy |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

Early life

Adolph Fischer was born in Bremen, Germany and attended school there for eight years. His father frequently attended socialist meetings, but in school Fischer was taught that socialism was an unhealthy lifestyle. However, after observing the working conditions in Germany, Fischer reached the opposite conclusion.

Fischer immigrated to the United States in 1873 at the age of 15. He became an apprentice compositor in a printing shop in Little Rock, Arkansas. Later, in 1879, he moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he joined the German Typographical Union and in 1881, married Johanna Pfauntz (they would have three children – one daughter and two sons). Adolph and his wife moved in 1881 to Nashville, Tennessee, where he worked for his brother as a compositor for Anzeiger des Südens, a journal for German immigrants.[1]

In 1883, he moved his family to Chicago, where he became a compositor at the Arbeiter-Zeitung, a pro-labor newspaper run by August Spies and Michael Schwab. It was around then that he also joined the International Working Person's Association and the Lehr-und-Wehr Verein, a radical offshoot which was formed to teach workers to defend themselves.

Haymarket Riot

Pre-riot

After the riot at the McCormick Reaper Plant on May 3, 1886, in which several workers were killed, Fischer attended a meeting at Greif's Hall, on Lake Street, to formulate a response. This was the infamous "Monday Night Conspiracy" which prosecution would use to prove foreknowledge of the bombing the following day. Also in attendance were George Engel and Godfried Waller, who chaired the meeting and who would later testify for the state in return for immunity (Waller was also arrested after the bombing).

The meeting concluded with a plan for a meeting the following night in the Haymarket. Fischer was charged with printing handbills to announce the meeting. The first handbills, which were printed in English and German, contained the line "Workingmen, arm yourselves and appear in full force."[2] Spies, who had been invited to speak at the meeting refused unless this line was removed, so Fischer prepared another circular without the offending line.[3]

Riot

Fischer attended the Haymarket meeting the following night and listened to speeches by Spies, Albert Parsons, and Samuel Fielden. Towards the end of Fielden's speech, he went to a local saloon, Zepf's Hall, which is where he was when the bomb and resulting riot occurred. After the commotion, he went home. He was arrested the following day. According to police he had in his possession at the time of his arrest, a loaded revolver, a sharpened file and a fulminating cap, used to detonate bombs.

Trial

The evidence presented against Fischer at trial consisted mainly of his role in the Monday Night Conspiracy and his role in printing the Haymarket circulars. His membership in the Lehr und Wehr Verein was also highlighted. Waller testified that Fischer had been the one who proposed the Haymarket meeting (Fischer claimed it was Waller) and that they should be ready to attack the police should there be any trouble.[4] He also testified that Fischer had given him a bomb the year previously, which he stated used against the police.[5] Another witness claimed that Fischer was standing with the bomb thrower at the time of the bombing.[6]

Fischer was convicted with the rest of the eight and, except for two who were given prison sentences, was sentenced to death by hanging.[7]

After two of his fellow defendants wrote to Illinois governor, Richard James Oglesby, Fischer pointedly refused to ask for clemency. He was hanged on November 11, 1887, along with Spies, Parsons and George Engel. His last words were, "Hurrah for anarchy! This is the happiest moment of my life!"[8]

Post-riot family life

After Adolph's death, his wife Johanna and children returned to the St. Louis area, living near her brother Rudolph Pfountz in Maplewood, a suburb of St Louis, Missouri.

See also

References

- Wood, E. Thomas (2008-05-02). "Nashville now and then: A fatal fervor". NashvillePost.com.

- "Illinois vs. August Spies et al. trial evidence book. People's Exhibit 5. "Attention Workingmen" flier, 1886 May 4." Chicago Historical Society.

- "Illinois vs. August Spies et al. trial evidence book. Defense Exhibit 1. "Attention Workingmen" flier, 1886 May 4." Chicago Historical Society.

- "Illinois vs. August Spies et al. trial transcript no. 1. Testimony of Godfried Waller (first appearance), 1886 July 16. Volume I, 53-75, 23 p." Chicago Historical Society.

- "Illinois vs. August Spies et al. trial transcript no. 1. Testimony of Godfried Waller (first appearance resumed), 1886 July 16. Volume I, 96-100, 5 p." Chicago Historical Society.

- "Illinois vs. August Spies et al. trial transcript no. 1. Testimony of Harry L. Gilmer (first appearance), 1886 July 28. Volume K, 405-497, 93 p." Chicago Historical Society.

- Linder, Douglas O. "Meet the Haymarket Defendants." Famous Trials: The Haymarket Riot Trial (State of Illinois v. Albert Spies, et al.). University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School of Law. Accessed December 30, 2017.

- Avrich, Paul (1984). The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-691-00600-0.

Works

- Autobiography of Adolph Fischer

- The Accused the Accusers: The Famous Speeches of the Chicago Anarchists in Court: On October 7th, 8th, and 9th, 1886, Chicago, Illinois. Chicago: Socialistic Publishing Society, n.d. [1886].

Further reading

- David, Henry. The History of the Haymarket Affair. New York: Collier Books, 1963.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Adolph Fischer |