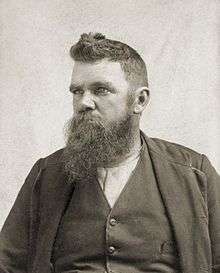

Samuel Fielden

Samuel "Sam" Fielden (February 25, 1847 – February 7, 1922) was an English-born American Methodist pastor, socialist, anarchist and labor activist who was one of eight convicted in the 1886 Haymarket bombing.

Biography

Early life

Samuel Fielden was born in Todmorden, Lancashire, England, to Abraham and Alice (née Jackson) Fielden. Fielden barely knew his mother, who died when he was 10 years old. His father was an impoverished foreman at a cotton mill and was, himself, an active labor and social activist. He was active in the 10-hour day movement in England and was also a chartist.[1]

Samuel Fielden went to work at the age of eight in the cotton mills and was impressed with the poor working conditions. He emigrated to the United States after he had come of age. In 1869, he moved to Chicago where he worked various jobs, sometimes even traveling to the south to pursue work opportunities. Finally he settled permanently in Chicago and became a self-employed teamster. He also studied Theology and became a lay preacher of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Although the church never ordained him, he served as a lay pastor in several congregations of workers in downtown Chicago.[1]

There he became acquainted with socialist thinking and in 1884, joined the cause full-time, becoming a member of the American Group faction of the International Working Men's Association, and later being appointed its treasurer. He became a frequent and eloquent speaker in the labor rights cause. He married in 1880 and had two children, the second of which was born while he was in prison.[2]

Haymarket

On May 4, 1886, Fielden was working delivering stone to German Waldheim Cemetery and had not heard of the planned demonstration at Haymarket for that night. He had promised to speak to some workers, but upon returning home, he learned of an urgent meeting of the American Group at the office of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, a German-language workers rights newspaper. Feeling it was his duty to attend this meeting as treasurer of the American Group, he abandoned his other engagement. It was only after he arrived at the meeting that he learned of the Haymarket demonstration.[3]

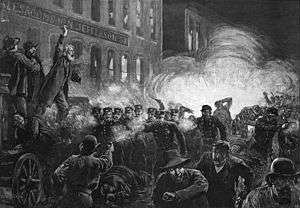

A short time later, there was a request from the Haymarket for additional speakers and Fielden, along with Albert Parsons, agreed to go and speak. They arrived just as August Spies was finishing a speech of his own. Parson then made a lengthy speech, but as the weather was growing threatening and the crowd growing thin, Fielden was reluctant to make a speech of his own, but was finally persuaded. He spoke for approximately 10 (reported as 20) minutes on the alliance of socialism and the working class and how the law - then current - was the enemy of the working man.[4]

Toward the end of his speech he was interrupted by a delegation of police who arrived headed by police captain John Bonfield who ordered the meeting to disperse. Fielden briefly protested before he stepped down from the wagon on which he had been speaking. At that moment, someone threw a bomb which exploded in the midst of the crowd. Fielden was shot and slightly wounded in the knee as he fled in the resulting chaos (he was the only Haymarket defendant to be wounded). After he had the wound dressed he returned home. He was arrested the following day and charged with conspiracy in the bombing.[5]

Trial and aftermath

At the trial, Fielden was accused of inciting the crowd to riot and violence. A Pinkerton detective reported that Fielden had, in the past, advocated the use of dynamite and the shooting of police officers.[6] Other witnesses declared that he had incited the crowd, proclaiming from the wagon as the police arrived, "Here comes the blood-hounds now; men do your duty and I will do mine".[7] Several police officers reported seeing Fielden produce a gun and fire into their ranks.[8][9][10] Fielden denied all of this and several other witnesses denied hearing Fielden make these remarks or seeing him fire any weapon.

Fielden was sentenced to death along with six other defendants, but after writing to Illinois governor Richard James Oglesby asking for clemency, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on November 10, 1887. He spent six years in prison until he was finally pardoned, along with co-defendants Michael Schwab and Oscar Neebe, by governor John Peter Altgeld on June 26, 1893. After being released, he purchased a ranch along Indian Creek in the La Veta valley of Colorado, where he made his home with his wife and children.[11]

Death and legacy

Sam Fielden died at his Colorado ranch in 1922 and is the only Haymarket defendant not buried near Chicago at the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument. Instead, he is buried with his wife Sarah (1845–1911), son Samuel Henry "Harry" (1886–1972), and daughter Alice (1884–1975)[12] at La Veta (Pioneer) Cemetery at Huerfano County, Colorado (though Fielden's own grave erroneously marks his year of birth as 1848).[13]

Works

- Autobiography of Samuel Fielden

- Testimony of Samuel Fielden, Illinois v. August Spies, Trial Transcript, Vol. M, 308-365, August 6, 1886.

- The Accused the Accusers: The Famous Speeches of the Chicago Anarchists in Court: On October 7th, 8th, and 9th, 1886, Chicago, Illinois. Chicago: Socialistic Publishing Society, n.d. [1886].

Footnotes

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, pp. 100–101.

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, pp. 102–103.

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, pp. 201–202.

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, pp. 202–206.

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, pp. 205–207, 229.

- HADC - Testimony of Andrew C. Johnson (first appearance), 1886 July 24. at Chicago Historical Society

- HADC - Testimony of Louis Haas (second appearance), 1886 July 27. at Chicago Historical Society

- HADC - Testimony of Charles Spierling, 1886 July 19. at Chicago Historical Society

- HADC - Testimony of Louis C. Baumann (first appearance), 1886 July 19. at Chicago Historical Society

- HADC - Testimony of Martin Quinn (first appearance), 1886 July 17. at Chicago Historical Society

- Lizzie M. Holmes, "Ranchman Fielden: The Peaceful Haven of a Storm-Tossed Life," St. Louis Union-Record, vol. 10, whole no. 300 (Aug. 31, 1895), pg. 2.

- http://kmitch.com/Huerfano/laveta/4-311.jpg

- Huerfano County La Veta Cem at kmitch.com

Works cited

- Avrich, Paul (1984). The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00600-0.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Samuel Fielden |