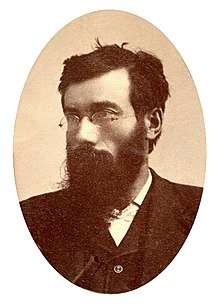

Michael Schwab

Michael Schwab (August 9, 1853 – June 29, 1898) was a German-American labor organizer and one of the defendants in the Haymarket Square incident.

Biography

Early years

Michael Schwab was born in Bad Kissingen, Franconia in Germany in 1853. He was a bookbinder by trade. Schwab emigrated to the United States in 1879 and lived variously in Chicago, Milwaukee and the Western U.S. before settling permanently in Chicago in 1881.

Schwab was married to the sister of Rudolph Schnaubelt (1863-1901), a Chicago anarchist believed by many to have actually thrown the bomb at Haymarket.[1] Together the couple would have three children.[1]

Activism

Schwab became an activist even before emigrating to the United States, having written articles for several radical German newspapers. He joined the German Social Democratic Party in 1872. In the U.S., he became involved in the workers' rights movement, first joining the Socialist Labor Party and later joining the International Working Persons Association and helping to form North-Side Group faction of that organization. He began writing and eventually became co-editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, an anarchist newspaper for German immigrant workers. He was very active in the 8-hour day movement.

Haymarket

On the night of May 4, 1886, Schwab left the office of Arbeiter-Zeitung, and stopped at the Haymarket meeting to look for fellow editor, August Spies. Not finding him, Schwab spoke briefly with his brother-in-law, Rudolph Schnaubelt, who was later accused of being the bombthrower. Schwab contended that he was at the Haymarket for no more than five minutes. He left there to speak at a meeting of workers at the Deering Reaper Works at the corner of Fullerton and Clybourn streets. This is where he remained throughout the bombing and left there to go straight home.

Schwab was arrested with the other six Haymarket rioters, while Albert Parsons turned himself in. In court, he was convicted along with his co-defendants and sentenced to death, while Oscar Neebe was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Amnesty and later years

Schwab wrote to Illinois governor Richard James Oglesby for lenience and on November 10, 1887, Oglesby commuted his sentence, along with that of Samuel Fielden, to life imprisonment. He served six years at Joliet Penitentiary before being pardoned with the other two by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld on June 26, 1893. After his release, he continued to write for the Arbeiter-Zeitung and opened a shoe store from which he also sold books on labor rights, but his health was poor since leaving prison and the store failed.

During his last years Schwab abandoned anarchist doctrine and embraced international socialism, speaking and writing in opposition to the notion of revolution by force.[1]

Death and legacy

Schwab was troubled by "intestinal and pulmonary troubles" during his last several years, for which he was hospitalized at the Alexian Brothers' Hospital in Chicago for the same on November 12, 1897.[1] He would remain hospitalized for the last seven months of his life, undergoing an operation in the middle of May 1898 in a vain effort to reverse his fate.[1] Schwab expired from his chronic internal ailment at 3:30 am on the morning of June 29, 1898.[1] He was 44 years old at the time of his death.

Arrangements for Schwab's funeral were handled by the Social Turnverein of Chicago, which announced plans for the cremation of Schwab's body immediately after his death at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.[1] Schwab was cremated the morning of July 6, with his ashes turned over to his widow for disposition at her pleasure.[2]

A memorial to Schwab was erected at Waldheim Cemetery where it stands along headstones of other Haymarket martyrs.

Footnotes

- "M. Schwab, the Anarchist, Passes Away," Chicago Dispatch, June 29, 1898, unspecified page. Copy preserved in The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834-1945 microfilm edition, reel 9.

- "M. Schwab's Body Burned: Ashes of Dead Socialist Leader Will be Disposed of By His Wife: Under No Circumstances Will They Be Buried at Waldheim Cemetery," Chicago Dispatch, July 6, 1898, unspecified page. Copy preserved in The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834-1945 microfilm edition, reel 9.

Works

- The Accused the Accusers: The Famous Speeches of the Chicago Anarchists in Court: On October 7th, 8th, and 9th, 1886, Chicago, Illinois. Chicago: Socialistic Publishing Society, n.d. [1886].

Further reading

- Testimony of Michael Schwab, Illinois v. August Spies, Trial Transcript, Vol. N, p. 1-17, August 9, 1886.

- Meet the Haymarket Defendants.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Michael Schwab |

- Chicago History: Michael Schwab

- John P. Altgeld, "Reasons for Pardoning Fielden, Neebe and Schwab," Chicago Historical Society, www.chicagohs.org/