Onnagata

Onnagata or oyama (Japanese: 女形・女方, "woman-role") are male actors who play women's roles in Japanese Kabuki theatre.[1]

History

The modern all-male kabuki was originally known as yarō kabuki ("man kabuki") to distinguish it from earlier forms. In the early 17th century, shortly after the emergence of the genre, many kabuki theaters had an all-female cast (onna kabuki), with women playing men's roles as necessary. Wakashū kabuki ("adolescent-boy kabuki"), with a cast composed entirely of attractive young men playing both male and female roles, and frequently dealing in erotic themes, originated circa 1612.[2](p90)

Both onnagata and wakashū (or wakashū-gata), actors specializing in adolescent female roles (and usually adolescents themselves), were the subject of much appreciation by both male and female patrons, and were often prostitutes. All-male casts became the norm after 1629, when women were banned from appearing in kabuki due to the prevalent prostitution of actresses and violent quarrels among patrons for the actresses' favors.[2](pp90–91) This ban failed to stop the problems, since the young male (wakashū) actors were also fervently pursued by patrons.

In 1642, onnagata roles were forbidden, resulting in plays that featured only male characters. These plays continued to have erotic content and generally featured many wakashū roles, often dealing in themes of nanshoku (male homosexuality); officials responded by banning wakashū roles as well.[2](p92) The ban on onnagata was lifted in 1644, and on wakashū in 1652, on the condition that all actors, regardless of role, adopted the adult male hairstyle with shaved pate. Onnagata and wakashū actors soon began wearing a small purple headscarf (murasaki bōshi or katsura) to cover the shaved portion, which became iconic signifiers of their roles and eventually became invested with erotic significance as a result.[2](p132) After authorities rescinded a ban on wig-wearing by onnagata and wakashū actors, the murasaki bōshi was replaced by a wig and now survives in a few older plays and as a ceremonial accessory.[3]

After film was introduced in Japan at the end of the 19th century, the oyama continued to portray females in movies until the early 1920s. At that time, however, using real female actresses was coming into fashion with the introduction of realist shingeki films. The oyama staged a protest at Nikkatsu in 1922 in backlash against the lack of work because of this. Kabuki, however, remains all-male even today.[4]

Oyama continue to appear in Kabuki today, though the term onnagata has come to be used much more commonly.

Every Kabuki actor is expected to have facility with onnagata techniques; and while it is tempting for Western opinion to equate onnagata with mere cross-dressing, or female impersonation, no kabuki actor's training is complete without mastery of what constitutes the techniques the Kabuki onnagata.

"Two Actors Combing Hair"; handpainted ukiyo-e scroll attributed to Hishikawa Morofusa, circa 1700. An onnagata wearing a purple headscarf combs the hair of a wakashū-gata (identifiable by his forelocks and partially shaved head).

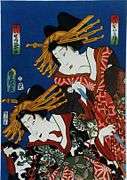

"Two Actors Combing Hair"; handpainted ukiyo-e scroll attributed to Hishikawa Morofusa, circa 1700. An onnagata wearing a purple headscarf combs the hair of a wakashū-gata (identifiable by his forelocks and partially shaved head). Nakamura Shikan IV and Sawamura Tanosuke III as Beautiful Woman/Keise Ikahoru. Print by Toyokuni in 1860, the year of Sawamura's debut under that name on the Kabuki stage.[lower-alpha 1]

Nakamura Shikan IV and Sawamura Tanosuke III as Beautiful Woman/Keise Ikahoru. Print by Toyokuni in 1860, the year of Sawamura's debut under that name on the Kabuki stage.[lower-alpha 1] Nakamura Utaemon V (1866–1940) as Yodo-gimi in the kabuki play Hototogisu Kojō no Rakugetsu

Nakamura Utaemon V (1866–1940) as Yodo-gimi in the kabuki play Hototogisu Kojō no Rakugetsu Nakamura Utaemon VI in costume, preparing to play a female kabuki role, 1951.

Nakamura Utaemon VI in costume, preparing to play a female kabuki role, 1951.- Popular onnagata Daigoro Tachibana dancing in a performance at the Miyoshibashi Theatre in Yokohama, November 2007. His crest, or teimon, can be seen on the red curtain behind him.

Bandō Tamasaburō V (center) in kabuki play Nihonbashi (December 2012)

Bandō Tamasaburō V (center) in kabuki play Nihonbashi (December 2012)

Notable onnagata

- Bandō Tamasaburō V

- Nakamura Utaemon VI

- Yoshizawa Ayame

- Taichi Saotome

- Sawamura Tanosuke III (1845–78; 三代目 沢村田之助; only occasionally Sawamura as 澤村).

See also

- Japanese Theatre

- Kagema for male prostitutes generally

- Cross-gender acting

- Drag show

- Köçek

- Pantomime dame

- Travesti (theatre)

- Womanless wedding

Notes

- Sawamura was, without question, one of the greatest 女形 of all time. Note here his blackened teeth, his お歯黒 [Ohaguro]. Sadly, he died prematurely in 1875, a triple amputee as a result of gangrene, leaving Japan sans a first-rate 女形 through 1900 and beyond (the efforts of Ichikawa Danjuro IX and Onoe Kikugoro V notwithstanding). Sawamura’s fashion sense set contemporaneous female taste, style which, to this day, pervades the Japanese psyche, especially evidenced in bridal wear. Few appeared with him as 女形—but Nakamura Shikan IV, here, was noted for his versatility, both in masculine, heroic roles, and in 女形.

References

- "Three Actors". World Digital Library. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- Leiter, Samuel L. (2006). Historical dictionary of Japanese traditional theatre. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 251. ISBN 0-8108-5527-5.

- Though there are all-female troupes, they represent a separate tradition, performing at separate theatres and for the most part not really playing a part in the 'core' kabuki world.