AIM-120 AMRAAM

The AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, or AMRAAM (pronounced AM-ram), is an American beyond-visual-range air-to-air missile (BVRAAM) capable of all-weather day-and-night operations. Designed with a 7-inch (180mm) diameter form-and-fit factor, and employing active transmit-receive radar guidance instead of semi-active receive-only radar guidance, it has the advantage of being a fire-and-forget weapon when compared to the previous generation Sparrow missiles. When an AMRAAM missile is launched, NATO pilots use the brevity code Fox Three.[11]

| AIM-120 AMRAAM | |

|---|---|

An AIM-120 AMRAAM mounted on the wingtip launcher of an F-16 Fighting Falcon | |

| Type | Medium-range, active radar homing air-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | September 1991–present |

| Used by | See operators |

| Wars | Operation Deny Flight Operation Allied Force Syrian civil war |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | • Hughes: 1991–97 • Raytheon: 1997–present |

| Unit cost | • $300,000–$400,000 for 120C variants • $1,786,000(FY2014) for 120D[1] US$1,090,000[2] (AIM-120D FY 2019) |

| Variants | AIM-120A, AIM-120B, AIM-120C, AIM-120C-4/5/6/7, AIM-120D |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 335 lb (152 kg) |

| Length | 12 ft (3.7 m) |

| Diameter | 7 in (180 mm) |

| Warhead | High explosive blast-fragmentation • AIM-120A/B: WDU-33/B, 50 pounds (22.7 kg) |

Detonation mechanism | Active RADAR Target Detection Device (TDD) Quadrant Target Detection Device (QTDD) in AIM-120C-6 – lots 13+.[3] |

| Engine | Solid-fuel rocket motor |

| Wingspan | 20.7 in (530 mm) AIM-120A/B |

Operational range | • AIM-120A/B: 55–75 km (30–40 nmi)[4][5] • AIM-120C-5: >105 km (>57 nmi)[6] |

| Maximum speed | Mach 4 (4,900 km/h; 3,045 mph)[8][9][10] |

Guidance system | inertial guidance, terminal active radar homing |

Launch platform | Aircraft:

Surface-launched:

|

The AMRAAM is the world's most popular beyond-visual-range missile, and more than 14,000 have been produced for the United States Air Force, the United States Navy, and 33 international customers.[12] The AMRAAM has been used in several engagements and is credited with ten air-to-air kills.[13] Now over 30 years old in design, the AMRAAM is due to be replaced by the new AIM-260 JATM, which will offer better long-range performance and ability to defeat electronic warfare jamming.[14]

Origins

AIM-7 Sparrow MRM

The AIM-7 Sparrow medium range missile (MRM) was purchased by the US Navy from original developer Hughes Aircraft in the 1950s as its first operational air-to-air missile with "beyond visual range" (BVR) capability. With an effective range of about 12 miles (19 km), it was introduced as a radar beam-riding missile and then it was improved to a semi-active radar guided missile which would home in on reflections from a target illuminated by the radar of the launching aircraft. It was effective at visual to beyond visual range. The early beam riding versions of the Sparrow missiles were integrated onto the F3H Demon and F7U Cutlass, but the definitive AIM-7 Sparrow was the primary weapon for the all-weather F-4 Phantom II fighter/interceptor, which lacked an internal gun in its U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and early U.S. Air Force versions. The F-4 carried up to four AIM-7s in built-in recesses under its belly.

Although designed for use against non-maneuvering targets such as bombers, because of poor performance against fighters over North Vietnam, these missiles were progressively improved until they proved highly effective in dogfights. Together with the short-range, infrared-guided AIM-9 Sidewinder, they replaced the AIM-4 Falcon IR and radar guided series for use in air combat by the USAF as well. A disadvantage to semi-active homing was that only one target could be illuminated by the launching fighter plane at a time. Also, the launching aircraft had to remain pointed in the direction of the target (within the azimuth and elevation of its own radar set) which could be difficult or dangerous in air-to-air combat.

An active-radar variant called the Sparrow II was developed to address these drawbacks, but the U.S. Navy pulled out of the project in 1956. The Royal Canadian Air Force, which took over development in the hopes of using the missile to arm their prospective CF-105 Arrow interceptor, soon followed in 1958.[15] The electronics of the time simply could not be miniaturized enough to make Sparrow II a viable working weapon. It would take decades, and a new generation of digital electronics, to produce an effective active-radar air-to-air missile as compact as the Sparrow.

AIM-54 Phoenix LRM

The US Navy later developed the AIM-54 Phoenix long-range missile (LRM) for the fleet air defense mission. It was a large 1,000 lb (500 kg), Mach 5 missile designed to counter cruise missiles and the bombers that launched them. Originally intended for the straight-wing Douglas F6D Missileer and then the navalized version of the F-111B, it finally saw service with the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, the only fighter capable of carrying such a heavy missile. Phoenix was the first US fire-and-forget, multiple-launch, radar-guided missile: one which used its own active guidance system to guide itself without help from the launch aircraft when it closed on its target. This, in theory, gave a Tomcat with a six-Phoenix load the unprecedented capability of tracking and destroying up to six targets beyond visual range, as far as 100 miles (160 km) away—the only US fighter with such capability.

A full load of six Phoenix missiles and its 2,000 pounds (910 kg) dedicated launcher exceeded a typical Vietnam-era bomb load. Its service in the US Navy was primarily as a deterrent, as its use was hampered by restrictive rules of engagement in conflicts such as Operations Desert Storm, Southern Watch, and Iraqi Freedom. The US Navy retired the Phoenix in 2004[16] in light of availability of the AIM-120 AMRAAM on the F/A-18 Hornet and the pending retirement of the F-14 Tomcat from active service in late 2006.

ACEVAL/AIMVAL

The Department of Defense conducted an extensive evaluation of air combat tactics and missile technology from 1974 to 1978 at Nellis AFB using the F-14 Tomcat and F-15 Eagle equipped with Sparrow and Sidewinder missiles as the blue force and aggressor F-5E aircraft equipped with AIM-9L all-aspect Sidewinders as the red force. This joint test and evaluation (JT&E) was designated Air Combat Evaluation/Air Intercept Missile Evaluation (ACEVAL/AIMVAL). A principal finding was that the necessity to produce illumination for the Sparrow until impact resulted in the red force's being able to launch their all-aspect Sidewinders before impact, resulting in mutual kills. What was needed was Phoenix-type multiple-launch and terminal active capability in a Sparrow-size airframe. This led to a memorandum of agreement (MOA) with European allies (principally the UK and Germany for development) for the US to develop an advanced, medium-range, air-to-air missile with the USAF as lead service. The MOA also assigned responsibility for development of an advanced, short-range, air-to-air missile to the European team; this would become the British ASRAAM.

Requirements

By the 1990s, the reliability of the Sparrow had improved so much from the dismal days of Vietnam that it accounted for the largest number of aerial targets destroyed in Desert Storm. But while the USAF had passed on the Phoenix and their own similar AIM-47/YF-12 to optimize dogfight performance, they still needed a multiple-launch fire-and-forget capability for the F-15 and F-16. AMRAAM would need to be fitted on fighters as small as the F-16, and fit in the same spaces that were designed to fit the Sparrow on the F-4 Phantom. The European partners needed AMRAAM to be integrated on aircraft as small as the Sea Harrier. The US Navy needed AMRAAM to be carried on the F/A-18 Hornet and wanted capability for two to be carried on a launcher that normally carried one Sparrow to allow for more air-to-ground weapons.

The AMRAAM became one of the primary air-to-air weapons of the new F-22 Raptor fighter, which needed to place all of its weapons into internal weapons bays in order to help achieve an extremely low radar cross-section.

Development

AMRAAM was developed as the result of an agreement (the Family of Weapons MOA, no longer in effect by 1990), among the United States and several other NATO nations to develop air-to-air missiles and to share production technology. Under this agreement the U.S. was to develop the next generation medium range missile (AMRAAM) and Europe would develop the next generation short range missile (ASRAAM). Although Europe initially adopted the AMRAAM, an effort to develop the Meteor, a competitor to AMRAAM, was begun in Great Britain. Eventually the ASRAAM was developed solely by the British, but using another source for its infrared seeker. After protracted development, the deployment of AMRAAM (AIM-120A) began in September 1991 in US Air Force F-15 Eagle fighter squadrons. The US Navy soon followed (in 1993) in its F/A-18 Hornet squadrons.

The Russian Air Force counterpart of AMRAAM is the somewhat similar R-77 (NATO codename AA-12 Adder), sometimes referred to in the West as the "AMRAAMski" Likewise, France began its own air-to-air missile development with the MICA concept that used a common airframe for separate radar-guided and infrared-guided versions.

Operational features summary

AMRAAM has an all-weather, beyond-visual-range (BVR) capability. It improves the aerial combat capabilities of US and allied aircraft to meet the threat of enemy air-to-air weapons as they existed in 1991. AMRAAM serves as a follow-on to the AIM-7 Sparrow missile series. The new missile is faster, smaller, and lighter, and has improved capabilities against low-altitude targets. It also incorporates a datalink to guide the missile to a point where its active radar turns on and makes terminal intercept of the target. An inertial reference unit and micro-computer system makes the missile less dependent upon the fire-control system of the aircraft.

Once the missile closes in on the target, its active radar guides it to intercept. This feature, known as "fire-and-forget", frees the aircrew from the need to further provide guidance, enabling the aircrew to aim and fire several missiles simultaneously at multiple targets and break a radar lock after the missile seeker goes active and guide themselves to the targets.

The missile also features the ability to "Home on Jamming,"[17] giving it the ability to switch over from active radar homing to passive homing – homing on jamming signals from the target aircraft. Software on board the missile allows it to detect if it is being jammed, and guide on its target using the proper guidance system.

Guidance system overview

Interception course stage

AMRAAM uses two-stage guidance when fired at long range. The aircraft passes data to the missile just before launch, giving it information about the location of the target aircraft from the launch point and its direction and speed. The missile uses this information to fly on an interception course to the target using its built-in inertial navigation system (INS). This information is generally obtained using the launching aircraft's radar, although it could come from an infra-red search and track system, from a data link from another fighter aircraft, or from an AWACS aircraft.

After launch, if the firing aircraft or surrogate continues to track the target, periodic updates—such as changes in the target's direction and speed—are sent from the launch aircraft to the missile, allowing the missile to adjust its course, via actuation of the rear fins, so that it is able to close to a self-homing distance where it will be close enough to "catch" the target aircraft in the basket (the missile's radar field of view in which it will be able to lock onto the target aircraft, unassisted by the launch aircraft).

Not all armed services using the AMRAAM have elected to purchase the mid-course update option, which limits AMRAAM's effectiveness in some scenarios. The RAF initially opted not to use mid-course update for its Tornado F3 force, only to discover that without it, testing proved the AMRAAM was less effective in beyond visual range (BVR) engagements than the older semi-active radar homing BAE Skyflash weapon—the AIM-120's own radar is necessarily of limited range and power compared to that of the launch aircraft.

Terminal stage and impact

Once the missile closes to self-homing distance, it turns on its active radar seeker and searches for the target aircraft. If the target is in or near the expected location, the missile will find it and guide itself to the target from this point. If the missile is fired at short range, within visual range (WVR) or the near BVR, it can use its active seeker just after launch to guide it to intercept.[18]

Boresight Visual mode

Apart from the radar-slaved mode, there is a free guidance mode, called "Visual". This mode is radar guidance-free—the missile just fires and locks onto the first thing it sees. This mode can be used for defensive shots, i.e. when the enemy has numerical superiority.

Kill probability and tactics

General considerations

The kill probability (Pk) is determined by several factors, including aspect (head-on interception, side-on or tail-chase), altitude, the speed of the missile and the target, and how hard the target can turn. Typically, if the missile has sufficient energy during the terminal phase, which comes from being launched at close range to the target from an aircraft with an altitude and speed advantage, it will have a good chance of success. This chance drops as the missile is fired at longer ranges as it runs out of overtake speed at long ranges, and if the target can force the missile to turn it might bleed off enough speed that it can no longer chase the target. Operationally, the missile, which was designed for beyond visual range combat, has a Pk of 63.15% (19 missiles for 12 kills, including the Syrian Su-22 downed by a US Navy F/A-18E).[19] The targets included six MiG-29s, a MiG-25, a MiG-23, two Su-22s, a Galeb and a US Army Blackhawk that was targeted by mistake.[20][21]

Variants and upgrades

Air-to-air missile versions

There are currently four main variants of AMRAAM, all in service with the United States Air Force, United States Navy, and the United States Marine Corps. The AIM-120A is no longer in production and shares the enlarged wings and fins with the successor AIM-120B. The AIM-120C has smaller "clipped" aerosurfaces to enable internal carriage on the USAF F-22 Raptor. AIM-120B deliveries began in 1994.

The AIM-120C deliveries began in 1996. The C-variant has been steadily upgraded since it was introduced. The AIM-120C-6 contained an improved fuse (Target Detection Device) compared to its predecessor. The AIM-120C-7 development began in 1998 and included improvements in homing and greater range (actual amount of improvement unspecified). It was successfully tested in 2003 and is currently being produced for both domestic and foreign customers. It helped the U.S. Navy replace the F-14 Tomcats with F/A-18E/F Super Hornets – the loss of the F-14's long-range AIM-54 Phoenix missiles (already retired) is offset with a longer-range AMRAAM-D. The lighter weight of the advanced AMRAAM enables an F/A-18E/F pilot greater bring-back weight upon carrier landings.

The AIM-120D is an upgraded version of the AMRAAM with improvements in almost all areas, including 50% greater range (than the already-extended range AIM-120C-7) and better guidance over its entire flight envelope yielding an improved kill probability (Pk). Raytheon began testing the D model on August 5, 2008, the company reported that an AIM-120D launched from an F/A-18F Super Hornet passed within lethal distance of a QF-4 target drone at the White Sands Missile Range.[22] The range of the AIM-120D is classified, but is thought to extend to about 100 miles (160 km).[7]

The AIM-120D (P3I Phase 4, formerly known as AIM-120C-8) is a development of the AIM-120C with a two-way data link, more accurate navigation using a GPS-enhanced IMU, an expanded no-escape envelope, and improved HOBS (high off-boresight) capability. The AIM-120D max speed is Mach 4[9] and AIM-120D is a joint USAF/USN project, and is currently in the testing phase. The USN was scheduled to field it from 2014, and AIM-120D will be carried by all Pacific carrier groups by 2020, although the 2013 sequestration cuts could push back this later date to 2022.[23] The Royal Australian Air Force requested 450 AIM-120D missiles, which would make it the first foreign operator of the missile. The procurement, approved by the US Government in April 2016, will cost $1.1 billion and will be integrated for use on the F/A-18F Super Hornet, EA-18G Growler and the F-35 Lightning II aircraft.[24]

There were also plans for Raytheon to develop a ramjet-powered derivative of the AMRAAM, the Future Medium Range Air-Air Missile (FMRAAM). The FMRAAM was not produced since the target market, the British Ministry of Defence, chose the Meteor missile over the FMRAAM for a BVR missile for the Eurofighter Typhoon aircraft.

Raytheon is also working with the Missile Defense Agency to develop the Network Centric Airborne Defense Element (NCADE), an anti-ballistic missile derived from the AIM-120. This weapon will be equipped with a ramjet engine and an infrared homing seeker derived from the Sidewinder missile. In place of a proximity-fused warhead, the NCADE will use a kinetic energy hit-to-kill vehicle based on the one used in the Navy's RIM-161 Standard Missile 3.[25]

The -120A and -120B models are currently nearing the end of their service life while the -120D variant has just entered full production. AMRAAM was due to be replaced by the USAF, the U.S. Navy, and the U.S. Marine Corps after 2020 by the Joint Dual Role Air Dominance Missile (Next Generation Missile), but it was terminated in the 2013 budget plan.[26] Exploratory work was started in 2017 on a replacement called Long-Range Engagement Weapon.

In 2017, work on the AIM-260 Joint Advanced Tactical Missile (JATM) began to create a longer-ranged replacement for the AMRAAM to contend with foreign weapons like the PL-15. Flight tests are planned to begin in 2021 and initial operational capability is slated for 2022, facilitating the end of AMRAAM production by 2026.[27]

Ground-launched systems

Raytheon successfully tested launching AMRAAM missiles from a five-missile carrier on a M1097 Humvee. This system will be known as the SLAMRAAM (Surface Launched (SL) and AMRAAM). They receive their initial guidance information from a radar not mounted on the vehicle. Since the missile is launched without the benefit of an aircraft's speed or high altitude, its range is considerably shorter. Raytheon is currently marketing an SL-AMRAAM EX, purported to be an extended range AMRAAM and bearing a resemblance to the RIM-162 ESSM.

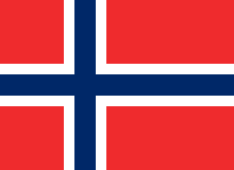

The Norwegian Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS), developed by Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace, consists of a number of vehicle-pulled launch batteries (containing six AMRAAMs each) along with separate radar trucks and control station vehicles. A more recent version of the program is the High Mobility Launcher, made in cooperation with Raytheon (Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace was already a subcontractor on the SLAMRAAM system), where the launch-vehicle is a Humvee (M1152A1 HMMWV), containing four AMRAAMs each.[28]

While still under evaluation for replacement of current US Army assets, the SL-AMRAAM has been deployed in several nations' military forces. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has requested the purchasing of SL-AMRAAM as part of a larger $7 billion foreign military sales package. The sale would include 288 AMRAAM C-7 missiles.[29]

The US Army has test fired the SL-AMRAAM from a HIMARS artillery rocket launcher as a common launcher, as part of a move to switch to a larger and more survivable launch platform.[30][31]

On January 6, 2011, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates announced that the U.S. Army has decided to terminate acquisition of the SLAMRAAM as part of a budget-cutting effort.[32]

The National Guard Association of the United States has sent a letter asking for the U.S. Senate to stop the Army's plan to drop the SLAMRAAM program because without it there would be no path to modernize the Guard's AN/TWQ-1 Avenger Battalions.[33]

On 22 February 2015, Raytheon announced an Extended Range upgrade to NASAMS-launched AMRAAM, calling it AMRAAM-ER. This combines the AMRAAM seeker with the ESSM rocket motor.[34]

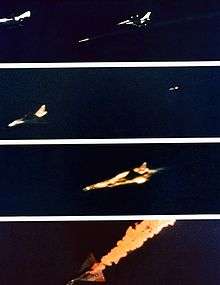

Operational history

The AMRAAM was used for the first time on December 27, 1992, when a USAF F-16D shot down an Iraqi MiG-25 that violated the southern no-fly-zone.[35] This missile had been returned from the flight line as defective a day earlier. AMRAAM gained a second victory in January 1993 when an Iraqi MiG-23 was shot down by a USAF F-16C.

The third combat use of the AMRAAM was in 1994, when a Republika Srpska Air Force J-21 Jastreb aircraft was shot down by a USAF F-16C that was patrolling the UN-imposed no-fly zone over Bosnia. In that engagement, at least three other Serbian aircraft were shot down by USAF F-16C fighters using AIM-9 missiles (see Banja Luka incident for more details). At that point, three launches in combat had resulted in three kills, resulting in the AMRAAM's being informally named "slammer" in the second half of the 1990s.

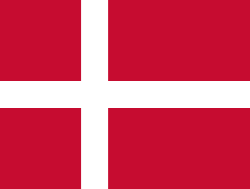

In 1998 and 1999 AMRAAMs were again fired by USAF F-15 fighters at Iraqi aircraft violating the No-Fly-Zone, but this time they failed to hit their targets. During spring 1999, AMRAAMs saw their main combat action during Operation Allied Force, the Kosovo bombing campaign. Six Serbian MiG-29 were shot down by NATO (four USAF F-15Cs, one USAF F-16C, and one Dutch F-16A MLU), all of them using AIM-120 missiles (the supposed kill by the F-16C may have actually been friendly fire, an SA-7 MANPADS fired by Serbian infantry).[13]

On 18 June 2017, a US F/A-18E Super Hornet engaged and shot down a Sukhoi Su-22 of the Syrian Air Force over northern Syria,[21] using an AIM-120. The Su-22 had previously avoided an AIM-9X Sidewinder; it was initially thought this was done by using flares,[36][37][38] although first-hand account by the F/A-18E pilot, Lt. Cmdr. Michael Tremel, was that the AIM-9X malfunctioned and failed to acquire the target, with no use of flares by the Su-22.[39]

As of 2017, the AIM-120 AMRAAM has shot down eleven aircraft (six MiG-29s, one MiG-25, one MiG-23, one Su-22, one Soko J-21 Jastreb, and one UH-60 Black Hawk).[13] The latter was a friendly fire incident in 1994 when two USAF F-15 fighters patrolling Iraq's Northern No-Fly Zone inadvertently shot down a pair of U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters, one by an AIM-9 Sidewinder.[40]

On 7 August 2018, a Spanish Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon accidentally launched a missile in Estonia.[41] There were no human casualties, but a ten-day search operation for missile remains was unsuccessful.[41][42]

On 27 February 2019, Pakistan Air Force downed an Indian Air Force MiG-21 Bison with its F-16s; Indian officials displayed fragments of the alleged AIM-120C-5 missile.[43] Pakistan denies the use of F-16 in this aerial engagement.

On 1 March 2020, Turkish Air Force downed two Su-24s belonging to the Syrian Assad regime using two AIM-120C7s that launched by an F-16.[44][45]

Foreign sales

Canadair, now Bombardier, had largely helped with the development of the AIM-7 Sparrow and Sparrow II, and assisted to a lesser extent in the AIM-120 development. Canada had placed an order for 256 AIM-120's, but cancelled half of them after engine ignition problems due to cold weather conditions. The AIM-9X & AIM-7 were ordered as replacements.

In early 1995 South Korea ordered 88 AIM-120A missiles for its KF-16 fleet. In 1997 South Korea ordered 737 additional AIM-120B missiles.[46][47]

In 2006 Poland received AIM-120C-5 missiles to arm its new F-16C/D Block 52+ fighters.[48]

In early 2006, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) ordered 500 AIM-120C-5 AMRAAM missiles as part of a $650 million F-16 ammunition deal to equip its F-16C/D Block 50/52+ and F-16A/B Block 15 MLU fighters. The PAF got the first three F-16C/D Block 50/52+ aircraft on July 3, 2010 and first batch of AMRAAMs on July 26, 2010.[49]

In 2007, the United States government agreed to sell 218 AIM-120C-7 missiles to Taiwan as part of a large arms sales package that also included 235 AGM-65G-2 Maverick missiles. Total value of the package, including launchers, maintenance, spare parts, support and training rounds, was estimated at around US$421 million. This supplemented an earlier Taiwanese purchase of 120 AIM-120C-5 missiles a few years ago.[48]

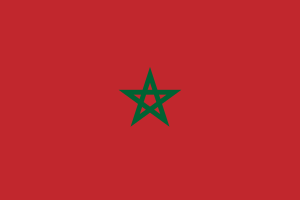

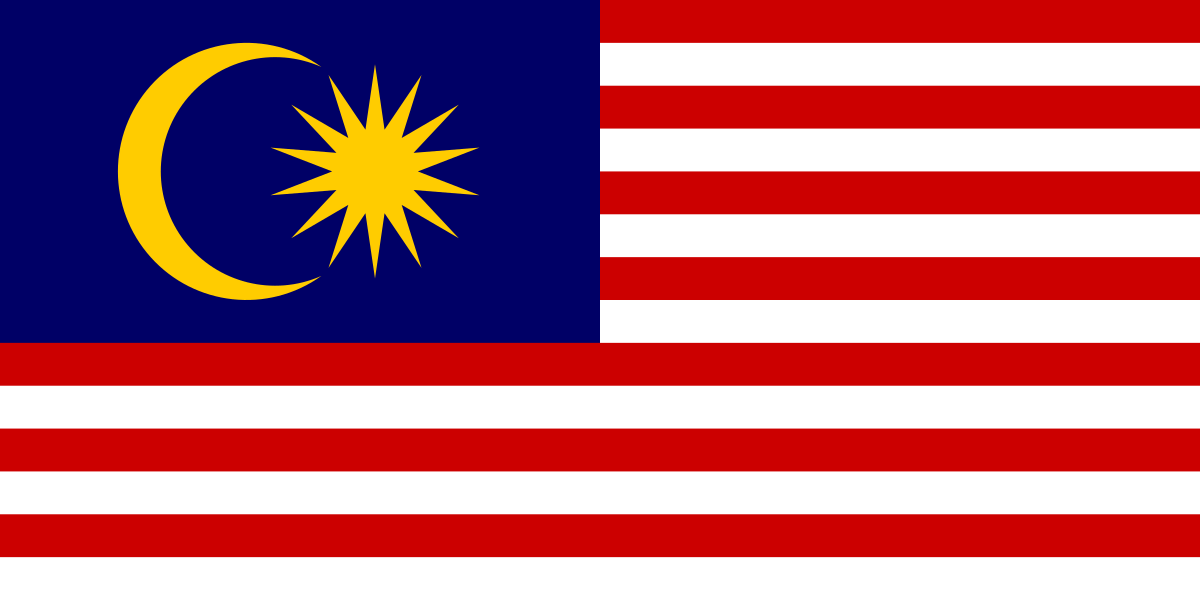

2008 has brought announcements of new or additional sales to Singapore, Finland, Morocco and South Korea; in December 2010 the Swiss government requested 150 AIM-120C-7 missiles.[50] Sales to Finland have stalled, because the manufacturer has not been able to fix a mysterious bug that causes the rocket motors of the missile to fail in cold tests.[51] In May 5, 2015, the State Department has made a determination approving a possible Foreign Military Sale to Royal Malaysian Air Force for AIM-120C7 AMRAAM missiles and associated equipment, parts and logistical support for an estimated cost of $21 million.[52][53]

In March 2016, the US government approved the sales of AIM-120C-7 missiles to the Indonesian Air Force to equip their fleet of F-16 C/D Block 52ID. The AIM-120C-7 is also equipped for the upgraded F-16 A/B Block 15 OCU through Falcon Star-eMLU upgrade project.[54][55][56]

In March 2019, the US Department of State and Defense Security Cooperation Agency have formally signed off on a US$240.5 million foreign military sale to support Australia’s introduction of the NASAMS and LAND 19 Phase 7B program. As part of the deal, the Australian government requested up to 108 Raytheon AIM-120C-7 AMRAAM, six AIM-120C-7 AMRAAM Air Vehicles Instrumented; and six spare AIM-120C-7 AMRAAM guidance sections.[57]

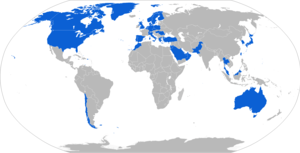

Operators

Current operators

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Japan Air Self-Defense Force (Test uses)

- Royal Air Force of Oman (RAFO)

- Pakistani Air Force

See also

Similar weapons

References

- Notes

- "United States Department Of Defense Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Request Program Acquisition Cost By Weapon System" (pdf). Office Of The Under Secretary Of Defense (Comptroller)/ Chief Financial Officer. March 2014. p. 53. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/32277/here-is-what-each-of-the-pentagons-air-launched-missiles-and-bombs-actually-cost. Retrieved February 15, 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Updated Weapons File" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC). 2003–2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - M-120, Designation Systems, archived from the original on January 30, 2005, retrieved January 8, 2005

- Richardson, Doug (2002), Stealth – Unsichtbare Flugzeuge (in German), Dietkion-Zürich: Stocker-Schmid, ISBN 978-3-7276-7096-1

- Aim-120c-5, Designation Systems, archived from the original on January 30, 2005, retrieved January 8, 2005

- "New long-range missile project emerges in US budget". November 2, 2017. Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- Parsch, Andreas. "Raytheon (Hughes) AIM-120 AMRAAM". Designation Systems. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Multi-service Air-Air, Air-Surface, Surface-Air brevity codes" (PDF). DTIC. April 25, 1997: 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Precision Strike: Enabler for Force Domination" (PDF). Air Armament Center, via DTIC. June 10, 2008. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Air Power Australia (March 15, 2008). "Air Power Australia: Technical Report APA-TR-2008-0301". Ausairpower.net. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 30, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/28636/meet-the-aim-260-the-air-force-and-navys-future-long-range-air-to-air-missile

- "Raytheon AIM/RIM-7 Sparrow". designation-systems.net. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Navy Retires AIM-54 Phoenix Missile, United States: Navy, archived from the original on March 5, 2011, retrieved November 26, 2011

- "Military Analysis Network: AIM-120 AMRAAM Slammer". FAS. April 14, 2000. Archived from the original on March 16, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- "AIM-120 AMRAAM". U.S. Air Force. U.S. Air Force. April 1, 2003.

- "Coffin Corners for the Joint Strike Fighter". ausairpower.net. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Dr C Kopp (March 15, 2008). "The Russian Philosophy of Beyond Visual Range Air Combat". ausairpower.net. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- "US coalition downs first Syria government jet." Archived September 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Raytheon Press Release, 5 August 2008 Archived November 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Greenert, Admiral Jonathan (September 18, 2013). "Statement Before The House Armed Services Committee on Planning For Sequestration in FY 2014 And Perspectives of the Military Services on the Strategic Choices And Management Review" (PDF). US House of Representatives. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- Drew, James (April 25, 2016). "Australia seeks DOD's newest air-to-air missile, the AIM-120D". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Defense Industry Daily report, 20 November 2008". Defenseindustrydaily.com. November 20, 2008. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- "USAF cancels AMRAAM replacement". Flight International. February 14, 2012. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- Air Force Developing AMRAAM Replacement to Counter China Archived June 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Air Force Magazine. 20 June 2019.

- "New capability in the NASAMS air defence system". Kongsberg.com. June 21, 2013. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- "DSCA Announces Billions in Military Sales". Aviation Week. September 11, 2008. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- HIMARS Launcher Successfully Fires Air Defense Missile Archived August 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Raytheon, Army test new SLAMRAAM platform". Upi.com. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- "Statement on Department Budget and Efficiencies" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. January 6, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- "U.S. Army Recommends SLAMRAAM Termination". Defensenews.com. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- Judson, Jen (October 4, 2016). "Raytheon's Extended Range AMRAAM Missile Destroys Target in First Flight Test". www.defensenews.com. Sightline Media Group. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- Bjorkman, Eileen, "Small, fast and in your face", Air & Space, February/March 2014, p. 35.

- Mizokami, Kyle (June 27, 2017). "How Did a 30-Year-Old Jet Dodge the Pentagon's Latest Missile?". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Browne, Ryan (June 22, 2017). "New details on US shoot down of Syrian jet". CNN. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- "A U.S. aircraft has shot down a Syrian government jet over northern Syria, Pentagon says" Archived June 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Rogoway, Tyler. "Here's The Definitive Account Of The Syrian Su-22 Shoot Down From The Pilots Themselves". www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- R. Gordon, Michael (April 15, 1994). "U.S. Jets Over Iraq Attack Own Helicopters in Error; All 26 on Board Are Killed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- "Spanish fighter jet accidentally fires missile In Estonia". Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- "Sanción mínima para el piloto al que se le escapó un misil en Estonia". Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- "After India Loses Dogfight to Pakistan, Questions Arise About Its 'Vintage' Military". New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Turkey shoots down two Syrian fighter jets over Idlib". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ŞAHİN, ANIL (March 1, 2020). "İki Su-24'ü aynı Türk pilotu vurdu". SavunmaSanayiST (in Turkish). Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "네이버 뉴스 라이브러리". naver.com. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- "AIM-120 AMRAAM Report Between 1995 and 2014". deagel.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- "Air-to-Air Missiles >> AIM-120 AMRAAM". www.deagel.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2011.

- Raytheon Press Release, 15 January 2007 Archived January 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "defence.professionals". defpro.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- "Outo vika pysäytti ohjuskaupan". HS.fi. September 3, 2012. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- "Malaysia-AIM-120C7 AMRAAM". Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- "US approves sale of AIM-120C7 AMRAAM missiles to Malaysia". airforce-technology.com. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- "Indonesia - AIM-120C-7 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAMs)". Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Franz-Stefan Gady. "US Clears Sale of Advanced Missiles to Indonesia". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Iwj, Pen Lanud. "Kasau Apresiasi Program Falcon Star-eMLU Pesawat F-16 A/B Block 15". TNI Angkatan Udara (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- Kuper, Stephen; Kuper, Stephen (March 14, 2019). "US approves foreign military sale for Australian Air Defence Capability". www.defenceconnect.com.au. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) (February 14, 2018). "The Military Balance 2018". The Military Balance. 118.

- Gurney, Kyra (August 15, 2014). "Infiltration of Chile Air Force Emails Highlights LatAm Cyber Threats". InSightCrime. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- "Czech Air force has bought 24 AMRAAMs". Radio.cz. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- "Raytheon Receives $19M Contract Modification for AMRAAM Missile Production Program". Defpost.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "AIM-120 ADVANCED MEDIUM-RANGE, AIR-TO-AIR MISSILE (AMRAAM)". The U.S. Navy. U.S. Navy. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Bibliography

- Bonds, Ray; Miller, David (2002). "AIM-120 AMRAAM". Illustrated Directory of Modern American Weapons. Zenith. ISBN 978-0-7603-1346-6.

- Clancy, Tom (1995). "Ordnance: How Bombs Got 'Smart'". Fighter Wing. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-255527-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AIM-120 AMRAAM. |

- Official website{{Dead link|date=August 2019 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}

- AIM-120 at Designation-Systems.

- Stephen Trimble (February 6, 2017). "ANALYSIS: Raytheon hits milestone for missile that changed air warfare". Flight Global. Washington, D.C.