Panavia Tornado ADV

The Panavia Tornado Air Defence Variant (ADV) is a long-range, twin-engine interceptor version of the swing-wing Panavia Tornado. The aircraft's first flight was on 27 October 1979, and it entered service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1986. It was also previously operated by the Italian Air Force (AMI) and the Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF).

| Tornado ADV | |

|---|---|

| |

| RAF Tornado F3 of No. 111 (Fighter) Squadron | |

| Role | Interceptor |

| Manufacturer | Panavia Aircraft GmbH |

| First flight | 27 October 1979 |

| Introduction | 1 May 1985 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force (historical) Royal Saudi Air Force (historical) Italian Air Force (historical) |

| Number built | 194[1] |

| Unit cost |

£14 million (1980)[2] |

| Developed from | Panavia Tornado IDS |

The Tornado ADV was originally designed to intercept Soviet bombers as they were traversing across the North Sea with the aim of preventing a successful air-launched nuclear attack against the United Kingdom. In this capacity, it was equipped with a powerful radar and beyond-visual-range missiles, however initial aircraft produced to the F2 standard lacked radars due to development issues. The F3 standard was the definitive variant used by the RAF, the RSAF and the AMI (which leased RAF aircraft).

During its service life, the Tornado ADV received several upgrade programmes which enhanced its aerial capabilities and enabled it to perform the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) mission in addition to its interceptor duties. Ultimately, both the RAF and RSAF retired their Tornado ADV fleets; the type has been replaced in both services by the Eurofighter Typhoon.

Design and development

Origins

The Tornado ADV had its origins in an RAF Air Staff Requirement 395 (or ASR.395), which called for a long-range interceptor to replace the Lightning F6 and Phantom FGR2.[3] The requirement for a modern interceptor was driven by the threat posed by the large Soviet long-range bomber fleet, in particular the supersonic Tupolev Tu-22M.[4] From the beginning of the Tornado IDS's development in 1968, the possibility of a variant dedicated to air defence had been quietly considered; several American aircraft had been evaluated, but found to be unsuitable.[5] However, the concept proved unattractive to the other European partners on the Tornado project, thus the UK elected to proceed in its development alone. On 4 March 1976, the development of the Tornado ADV was approved and it was announced that 165 of the 385 Tornados that were on order for the RAF would be of the air defence variant.[6][7]

In 1976, The British Aircraft Corporation was contracted to provide three prototype aircraft.[7][8] The first prototype was rolled out at Warton on 9 August 1979, before making its maiden flight on 27 October 1979 with David Eagles.[7] The second and third development aircraft made their first flights on 18 July and 18 November 1980, respectively.[6][4] During the flight testing, the ADV demonstrated noticeably superior supersonic acceleration to the IDS, even while carrying a full weapons loadout.[9] The testing of the prototypes was greatly aided by the use of real-time telemetry being broadcast back to ground technicians from aircraft in flight.[10] The third prototype was primarily used in the testing of the new Marconi/Ferranti AI.24 Foxhunter airborne interception radar.[6][11]

The Tornado ADV's differences compared to the IDS include a greater sweep angle on the wing gloves, and the deletion of their kruger flaps, deletion of the port cannon, a longer radome for the Foxhunter radar, slightly longer airbrakes and a fuselage stretch of 1.36 m to allow the carriage of four Skyflash semi-active radar homing missiles.[3][12] The stretch was applied to the Tornado front fuselage being built by the UK, with a plug being added immediately behind the cockpit, which had the unexpected benefit of reducing drag and making space for an additional fuel tank (Tank '0') carrying 200 imperial gallons (909 L; 240 U.S. gal) of fuel.[13] The artificial feel of the flight controls was lighter on the ADV than on the IDS.[14] Various internal avionics, pilot displays, guidance systems and software also differed.[15]

The Tornado F2 was the initial version of the Tornado ADV in Royal Air Force service, with 18 being built. It first flew on 5 March 1984 and was powered by the same RB.199 Mk 103 engines used by the IDS Tornado, capable of four wing sweep settings, and fitted to carry only two underwing Sidewinder missiles.[16] Serious problems were discovered with the Foxhunter radar, which meant that the aircraft were delivered with concrete and lead ballast installed in the nose as an interim measure until they could be fitted with the radar sets. The ballast was nicknamed Blue Circle, which was a play on the Rainbow Codes nomenclature, and a British brand of cement called Blue Circle.[3][17]

Tornado F3

Production of the Tornado ADV was performed between 1980 and 1993.[6] The Tornado F3 made its maiden flight on 20 November 1985.[7] Enhancements over the F2 included RB.199 Mk 104 engines, which were optimised for high-altitude use with longer afterburner nozzles, the capacity to carry four underwing Sidewinder missiles rather than two, and automatic wing sweep control.[17] The F3's primary armament when it entered into service was the short-range Sidewinder and the medium-range Skyflash missiles, a British design based on the American AIM-7 Sparrow.[18] The F.3 (originally F.Mk3) became operational in 1989, with an automatic maneuver device system incorporated, enabling the flight control computer to automatically adjust the sweeping the wing to obtain the optimum flight characteristics. This was similar in concept to the automatic sweeping wing (ASW) capability of F-14, a capability that greatly enhanced maneuverability but did not exist on any previous Tornado IDS and ADV models.[19]

Capability Sustainment Programme

In order to maintain the Tornado F3 as an effective platform up to its planned out-of-service date of 2010, the Ministry of Defence initiated the Capability Sustainment Programme (CSP). This £125 million project, announced on 5 March 1996, involved many elements, including the integration of ASRAAM and AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missiles, and radar upgrades to improve multi-target engagement. Additionally, pilot and navigator displays would be improved, along with the replacement of several of the onboard computer systems.[20][21] The CSP saw the removal of a non-standard state of aircraft; various upgrades, in particular to the Foxhunter radar, had led to a situation described as "fleets within fleets".[20] The Foxhunter radar caused difficulties in the upgrade programme, in particular the integration of the new AMRAAM missile.[22]

Cost saving decisions meant that the CSP did not fully exploit the capabilities of the AMRAAM or ASRAAM missiles. AMRAAM uses two mid-course updates after launch to refresh target information prior to its own seeker taking over; however, the CSP did not include the necessary datalink to provide this capability. The ASRAAM was not fully integrated, which prevented the full off-boresight capability of the missile being used.[23] However, in June 2001, the MoD signed a contract for a further upgrade to allow for these midcourse updates.[24] This upgrade, together with updated IFF, was known as the AMRAAM Optimisation Programme (AOP) and was incorporated in the remaining F3 fleet between December 2003 and September 2006.[24]

A further upgrade, disclosed in early 2003, was the integration of the ALARM anti-radiation missile to enable several Tornado ADVs to conduct Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) missions.[25] The F3's existing radar warning receivers formed the basis of an Emission Location System (ELS), which can be employed to detect and locate operational radar systems in the aircraft's vicinity. These modified aircraft were re-designated Tornado EF3 and operated by No. 11 Squadron RAF.[26]

Performance

According to aviation historian Michael Leek, from the onset of the type's development, the Tornado ADV encountered "...controversy and many questions over the ADV's performance and suitability - controversy which stayed with the aircraft for much of its service life".[6]

The Tornado ADV was designed to serve in the role of an interceptor against the threat of Soviet bombers, rather than as an air superiority fighter for engaging in prolonged air combat manoeuvering with various types of enemy fighters.[12] In order to perform its anti-bomber primary mission, it was equipped with long range beyond visual range missiles such as the Skyflash, and later the AMRAAM; the aircraft also had the ability to stay aloft for long periods and remain over the North Sea and Northern Atlantic in order to maintain its airborne patrol.[27]

The capability of its weapon systems was a dramatic improvement over its predecessors.[28] Compared with the Phantom, the Tornado had greater acceleration, twice the range and loiter time, and was more capable of operating from short 'austere' air strips.[29] Older aircraft were reliant on a network of ground-based radar stations, but the F3's Foxhunter radar was capable of performing much longer and wider scans of surrounding airspace; the Tornado could track and engage targets at far greater distances.[12] The Tornado also had the ability to share its radar and targeting information with other aircraft via JTIDS/Link 16 and was one of the first aircraft to have a digital data bus, used for the transmission of data between onboard computers.[30][31]

Operational history

Royal Air Force

On 5 November 1984, the first interim Tornado F2 was first delivered to the RAF, and its short career came to an end shortly following the improved Tornado F3 entered service. These aircraft were used primarily for training by No. 229 Operational Conversion Unit RAF until they were placed in storage. The F2s were intended to be updated to Tornado F2A standard (similar to the F3 but without the engine upgrade) but only one F2A, the Tornado Integrated Avionics Research Aircraft (TIARA) was converted, having been customised by QinetiQ for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) trials at MoD Boscombe Down.[32]

In November 1987, No. 29 (Fighter) Squadron became the first RAF squadron to be declared operational with the Tornado ADV.[6]

The Tornado F3 made its combat debut in the 1991 Gulf War with 18 aircraft deployed to Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The aircraft deployed to the region were later upgraded in a crash program with improved radar and engines, better defensive countermeasures and several adaptions to the weapons systems to improve combat performance in the Iraqi theatre;[33] however, they still lacked modern IFF and secure communications equipment. They therefore flew patrols further back from Iraqi airspace where encounters with enemy aircraft were less likely, and did not get the opportunity to engage any enemy aircraft.[34] From August 1990 to March 1991, the RAF's F3 detachment flew more than 2000 combat air patrol sorties.[35]

Following the Gulf War, the RAF maintained a small squadron of F3s in Saudi Arabia to continue routine patrols of Iraqi no-fly zones. The Tornado F3 saw further combat service, from 1993 to 1995 as escort fighters in Operation Deny Flight over Bosnia, and in 1999 flying combat air patrols during Operation Allied Force in Yugoslavia;[36] during these extended overseas deployments, the F3 proved troublesome to maintain at operational readiness when based outside the UK.[37] Following lengthy delays in the Eurofighter programme to develop a successor to the F3 interceptor, in the late 1990s the RAF initiated a major upgrade program to enhance the aircraft's capabilities, primarily by integrating several newer air-to-air missiles.[38]

In 2003, the Tornado F3 was one of the assets used in Operation Telic, Britain's contribution to the Iraq War. An expeditionary force composed of No. 43 (F) and No. 111 (F) Squadrons (known as Leuchars Fighter Wing) was deployed to the region to carry out offensive counter-air operations. The Tornado F3's of Leuchars Fighter Wing operated all over Iraq, including missions over and around Baghdad, throughout Operation Telic. Due to a lack of airborne threats materialising in the theatre, the F3s were withdrawn and returned to European bases that same year.[39]

As part of the Delivering Security in a Changing World White Paper, on 21 July 2004, Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon detailed plans to reduce the number of Tornado F3 squadrons by one to three squadrons.[40] This represented 16 aircraft and was the first stage in the transition to the F3's replacement, the Eurofighter Typhoon, which entered operational service with the RAF in 2005. In April 2009, it was announced that the Tornado F3 force would be reduced to one squadron of 12 aircraft in September 2009.[41] The last operational Tornado F3s in RAF service were retired when No. 111 (F) Squadron, located at RAF Leuchars, was disbanded on 22 March 2011.[42]

In addition to the RAF's Tornado F3s, in 2007, QinetiQ leased four Tornado F3s from the MOD for the purpose of conducting weapons testing activities.[43] QinetiQ's force of four F3s remained flying beyond the RAF's retirement of the type, in their latter service they were being used for aerial testing of the new MBDA Meteor air-to-air missile, and thus were the only flying examples in the UK for a time. Their final mission was flown on 20 June 2012, and the last three flown to RAF Leeming for scrapping on 9 July 2012.[6][44]

Italian Air Force

In the early 1990s, the Italian Air Force (Aeronautica Militare Italiana, or AMI) identified a requirement for a fighter to boost its air defence capabilities pending introduction of the Eurofighter Typhoon, expected around 2000.[45] These fighters were to operate alongside the service's obsolescent F-104ASA Starfighters. The Tornado ADV was selected from, amongst others, the F-16. On 17 November 1993, Italy signed an agreement with the RAF to lease 24 Tornado F3s from the RAF for a period of ten years. The lease included 96 Sky Flash TEMP missiles (a lower standard than the version in RAF service), training, logistical supply for ADV-specific equipment and access to the RAF facility at Saint Athan.[46]

First training of AMI pilots began in March 1995 at RAF Coningsby while technicians gained experience at RAF Cottesmore and Coningsby. The first aircraft was accepted on 5 July 1995 and flown to its Italian base the same day. Delivery of the first batch was completed by 1996; these aircraft were deployed at Gioia del Colle in Southern Italy.[47] The second batch was delivered between February and July 1997, these aircraft were of a slightly higher specification.[46] In early 1997, the AMI cancelled a series of scheduled upgrades to its Tornado fleet, stating that it was placing priority for funding on the developing Eurofighter instead.[48]

The Tornado proved unreliable in Italian service, achieving serviceability rates of 50% or less. Air Forces Monthly ascribed to the AMI underestimating the different support requirements versus the Tornado IDS, a lack of spare engines (which were not included in the lease agreement), and a lack of equipment.[46]

In 2000, with major delays hampering the Eurofighter, the AMI began a search for another interim fighter. While the Tornado itself was considered, any long term extension to the lease would have involved upgrade to RAF CSP standard and structural modifications to extend the airframes' service life and thus was not considered cost effective.[46] In February 2001, Italy announced its arrangement to lease 35 F-16s from the United States.[49] The AMI returned its Tornados to the RAF, with the final aircraft arriving at RAF Saint Athan on 7 December 2004. One aircraft was retained by the Italian Air Force for static display purposes.[50]

Royal Saudi Air Force

On 26 September 1985, Saudi Arabia and Britain signed a memorandum of understanding towards what would be widely known as the Al-Yamamah arms deal, for the provision of various military equipment and services.[51] The September 1985 deal involved the purchase of a large number of Tornado aircraft; including the Tornado ADV variant, along with armaments, radar equipment, spare parts and a pilot-training programme for the inbound fleet, in exchange for providing 600,000 barrels of oil per day over the course of several years.[52] The first Al-Yamamah agreement ordered 24 Tornado ADVs and 48 Tornado IDSs.[52] The RSAF received its first ADV on 9 February 1989.[7]

Historian Anthony Cordesman commented that "the Tornado ADV did not prove to be a successful air defence fighter... The RSAF's experience with the first eight Tornado ADVs was negative".[53] In 1990, the RSAF signed several agreements with the US to later receive deliveries of the McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle, and thus had a reduced need for the Tornado ADV;[54] Saudi Arabia chose to convert further orders for up to 60 Tornado ADVs to the IDS strike variant instead.[55]

In 1991, during Operation Desert Storm over neighbouring Iraq, RSAF Tornado ADVs flew 451 air-defence sorties, operating in conjunction with RSAF F-15s.[56] In 2006, it was announced that, in addition to Saudi Arabia's contract to purchase the Eurofighter Typhoon, both the Tornado IDS and ADV fleets would undergo a £2.5 billion program of upgrades, allowing them to remain in service to at least 2020.[57] The Eurofighter has now replaced the Tornado ADV in the air-defence role.[42]

Variants

- Tornado F2

- Two-seat all-weather interceptor fighter aircraft, powered by two Turbo-Union RB.199-34R Mk 103 turbofan engines. Initial production version, 18 built.

- Tornado F2A

- F2 upgrade to F3 standard, but retaining F2 engines, one converted.

- Tornado F3

- Improved version, powered by two Turbo-Union RB.199-34R Mk 104 engines, with automatic wing sweep control, increased AIM-9 carriage and avionics upgrades.[17] 171 built for the Royal Air force (RAF) and Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF).

- Tornado EF3

- Unofficial designation for F3 aircraft modified with ALARM missile capability.[25]

Operators

- Italian Air Force (1995–2004)

- Gioia del Colle Air Base, Bari

- 12° Gruppo (1995–2004)

- 21° Gruppo (1999–2001)

- Cameri Air Base, Novara

- 21° Gruppo (1997–1999)

- Gioia del Colle Air Base, Bari

- Royal Saudi Air Force (1989–2006)

- Dhahran Airfield, Eastern Province

- 29th Squadron (1989–2006)

- 34th Squadron (1989–1992)

- Dhahran Airfield, Eastern Province

- Royal Air Force (1979–2011)

- RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, England

- No. V (AC) Squadron (1987–2003)[60]

- No. 29 (F) Squadron (1987–1998)[61]

- No. 41 (R) Squadron (2006–2011)[62][63]

- No. 65 (R) Squadron (Shadow identity of No. 229 OCU) (1986–1992)

- No. 56 (R) Squadron (1992–2003)[65]

- No. 229 Operational Conversion Unit RAF (1984–2003)

- RAF Leeming, North Yorkshire, England

- No. XI (F) Squadron (1988–2005)[66]

- No. 23 (F) Squadron (1988–1994)[67]

- No. XXV (F) Squadron (1989–2008)[68]

- RAF Leuchars, Fife, Scotland

- No. 43 (F) Squadron (1989–2009)[69]

- No. 56 (R) Squadron (2003–2008)[65]

- No. 111 (F) Squadron (1990–2011)[70]

- RAF Mount Pleasant, East Falkland, Falkland Islands

- No. 1435 Flight (1992–2009)

- RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, England

Specifications (Tornado F3)

.jpg)

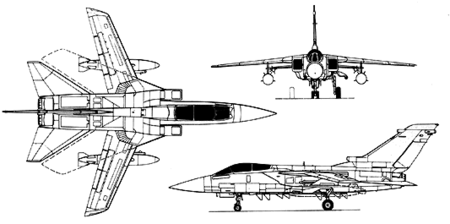

| Tornado ADV F2 cutaway illustration | |

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1993–94,[71]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 18.68 m (61 ft 3 in)

- Wingspan: 13.91 m (45 ft 8 in) at 25° sweep

- 8.6 m (28 ft) at 67° sweep

- Height: 5.95 m (19 ft 6 in)

- Wing area: 26.6 m2 (286 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 14,500 kg (31,967 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 27,986 kg (61,699 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Turbo-Union RB199-34R afterburning 3-spool turbofan, 40.5 kN (9,100 lbf) thrust each dry, 73.5 kN (16,500 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 2,400 km/h (1,500 mph, 1,300 kn) / M2.2 at 9,000 m (29,528 ft)

- 1,482 km/h (921 mph; 800 kn) near sea level

- Combat range: 1,853 km (1,151 mi, 1,001 nmi) subsonic

- >556 km (345 mi) supersonic

- Ferry range: 4,265 km (2,650 mi, 2,303 nmi) with four external tanks[72]

- Endurance: 2 hr combat air patrol at 560–740 km (348–460 mi) from base

- Service ceiling: 15,240 m (50,000 ft) [73]

Armament

- Guns

- 1 × 27 mm (1.063 in) Mauser BK-27 revolver cannon with 180 rounds (internally mounted under starboard side of fuselage, versus 2× BK-27 mounted on Panavia Tornado IDS)

- Hardpoints: 10 total (4× semi-recessed under-fuselage, 2× under-fuselage, 4× swivelling under-wing) holding up to 9000 kg (19,800 lb) of payload, the two inner wing pylons have shoulder launch rails for 2× Short-Range AAM (SRAAM) each

- 4× AIM-9 Sidewinder or ASRAAM

- 4× British Aerospace Skyflash or AIM-120 AMRAAM (mounted on 4 semi-recessed under-fuselage hardpoints)

- Others:

- Up to 2× drop tanks for extended range/loitering time. Up to 4 drop tanks for ferry role (at the expense of 4 Skyflash/AMRAAM).

Avionics

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References

Citations

- "Panavia Tornado ADV total production source from panavia homepage".

- Pym, Francis. "Armaments (Replacement Cost)". millbanksystems. Hansard. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Laming 1996, p. 97.

- Eden 2004, p. 370

- Aeroguide 21 1988, p. 3.

- Leek 2015, p. 23

- Taylor 2001, pp. 189–190

- Aeroguide 21 1988, p. 1.

- Eagles 1991, p. 91.

- Eagles 1991, pp. 90–91.

- Eagles 1991, p. 92.

- Eagles 1991, p. 88.

- Evans 1999, p.121

- Eagles 1991, p. 89.

- Aeroguide 21 1988, pp. 6–7.

- Aeroguide 21 1988, p. 7.

- Evans 1999, p. 126

- Butler 2001, p. 101.

- Panavia Tornado ADV (Air Defense Variant)

- Nicholas 2000, pp. 29–30.

- Nicholas, Jack C (July 2000). "Sustaining the F.3". Air International. Key Publishing.

- Hall, Macer "RAF abandons missile system after near miss." The Telegraph, 23 January 2002.

- Nicholas 2000, p. 30.

- Willis, David (December 2007). "Tornado F.3 – At its Peak". Air International. 73 (6). Stamford, Lincs, England: Key Publishing. pp. 22–26. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "Tornado F3". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- "Welcome to the VRAF: Number XI Squadron". VRAF.org. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Butler 2001,

- Smith 1980, p. 134.

- Aeroguide 21 1988, p. 2.

- Moir and Seabridge 2011, pp. 447–448.

- Aeroguide 21 1988, p. 6.

- "Pilotless Passenger Jet Flown Remotely By RAF." Archived 29 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force, 3 April 2007.

- Szejnmann 2010, pp. 214–215.

- Lake 1997, p. 126.

- Szejnmann 2010, p. 216.

- McGrath, Mark. "Tornado F3 Bows Out." Fence Check, Retrieved: 11 July 2012.

- Szejnmann 2010, pp. 221–222.

- Szejnmann 2010, p. 222.

- "U.K. Begins Moving Some Forces Home."newsmax.com, 12 April 2003. Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Hoon announces broad military cuts." The Scotsman, 21 July 2004.

- Urquhart, Frank (17 April 2009). "Historic squadron is disbanded – but Fighting Cocks may fly again". The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- Hoyle, Craig. "UK retires last Tornado F3 fighters." Flight International, 22 March 2011.

- "QinetiQ wins contract to use Tornado F3 for BVRAAM trials." Archived 9 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine QinetiQ, 16 May 2007.

- Lake, Jon. "Meteor Development Complete". Air International, Vol 83 No 2, August 2012, p. 8.

- Bevins, Anthony and Chris Godsmark. "£15bn go-ahead for Eurofighter." The Independent, 3 September 1996.

- Sacchetti, Renzo (October 2003). "Italy's British Tornados". AirForces Monthly. Key Publishing. pp. 50–54.

- "Italian air force faces tough 12 months as cash cuts bite." Flight International, 11 January 1995.

- "Italy cuts projects to protect EF2000 interest". Flight International, 12 March 1997.

- "Italy to lease 35 F-16 jets from USA until Eurofighter operational". ANSA News Agency, 1 February 2001.

- "Final AMI Tornados F3s Returned". AirForces Monthly. Key Publishing. February 2005. p. 9.

- "Briefing for the Prime Minister's Meeting with Prince Sultan." Ministry of Defence, 26 September 1985.

- Cordesman 2003, pp. 217–218.

- Cordesman 2003, pp. 218–219.

- "BAE official denies reports of Tornado sale cancellation." Defense Daily, 5 October 1990.

- Cordesman 2003, pp. 219.

- Al Saud, Turki K. "The Royal Saudi Air Force and Long-term Saudi National Defence: A Strategic Vision." United States Marines Corps Command and Staff College, 6 May 2002.

- "The 2006 Saudi Shopping Spree: BAE Wins Tornado Fleet Upgrade Contract." Defense Industry Daily, 12 September 2006.

- "5 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "29 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "41 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "41 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "56 (Reserve) Squadron". RAF Leuchars. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "11 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "23 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "25 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "No 43 (Fighter) Squadron Disbanded". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 10 December 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Historic RAF squadron disbanded as F3 retires". gov.uk. Ministry of Defence. 5 April 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Lambert 1993, pp. 173–175.

- Mason 1992, p. 424.

- RAF: Equipment – Tornado F3 Specifications Archived 14 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Air Force. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

Bibliography

- Aeroguide 21: Panavia Tornado F Mk 2/Mk 3. Ongar, UK: Linewrights Ltd. 1988. ISBN 0-946958-26-2.

- Butler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Jet Fighters Since 1950. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-095-8.

- Cordesman, Anthony. Saudi Arabia Enters the Twenty-first Century: The military and international security dimensions. Greenwood Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-275-97997-0.

- Eden, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Eagles, J.D. "Preparing a Bomber Destroyer: The Panavia Tornado ADV." Putnam Aeronautical Review (Naval Institute Press), Volume 2, 1991, pp. 88–93.

- Evans, Andy. Panavia Tornado. Wiltshire UK: Crowood Press, 1999. ISBN 1861262019.

- Jackson, Robert. Air War at Night. Charlottesville, Virginia: Howell Press Inc. 2000. ISBN 1-57427-116-4 (see pp. 139–144).

- Lake, Jon. "Panavia Tornado Variant Briefing:Part Two". World Air Power Journal, Volume 31, Winter 1997. London: Aerospace Publishing. pp. 114–131. ISBN 1-86184-006-3. ISSN 0959-7050.

- Lambert, Mark. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1993–94. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Data Division, 1993. ISBN 0-7106-1066-1.

- Laming, Tim. Fight's On: Airborne with the Aggressors. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, 1996. ISBN 0-7603-0260-X.

- Leek, Michael. The Panavia Tornado: A Photographic Tribute. Pen and Sword, 2015. ISBN 1-4738-6914-5.

- Nicholas, Jack C. "Sustaining the F.3". Air International, July 2000, Vol 59 No 1. pp. 28–31. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Fighter since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55750-082-7.

- Moir, Ian and Allan Seabridge. Aircraft Systems: Mechanical, Electrical and Avionics Subsystems Integration. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2011. ISBN 1-119-96520-9.

- Smith, Dan. The defence of the realm in the 1980s. Taylor & Francis, 1980. ISBN 0-85664-873-6.

- Szejnmann, Claus-Christian W. Rethinking History, Dictatorship and War: New Approaches and Interpretations. Continuum International, 2010. ISBN 0-82644-323-0.

- Taylor, Michael J.H (2001). Flight International World Aircraft & Systems Directory (3rd ed.). United Kingdom: Reed Business Information. ISBN 0-617-01289-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panavia Tornado. |

- Panavia website

- BAe Tornado at FAS.org

- Tornado ADV at Aerospaceweb.org

- Unofficial Panavia Tornado site