2017 German federal election

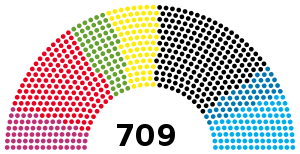

Federal elections were held in Germany on 24 September 2017 to elect the members of the 19th Bundestag. At stake were all 598 seats in the Bundestag, as well as 111 overhang and leveling seats determined thereafter.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 709 seats in the Bundestag, including 111 overhang and leveling seats 355 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 61,688,485 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 46,976,341 (76.2%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

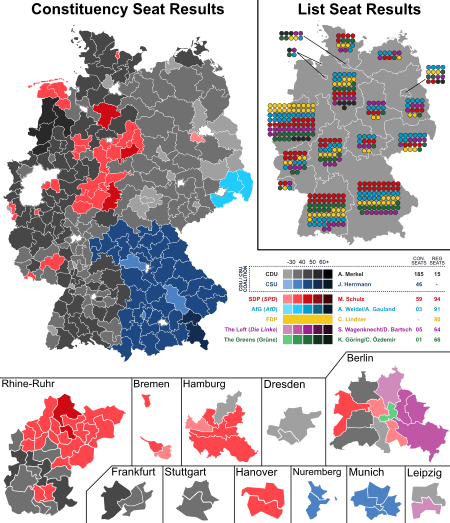

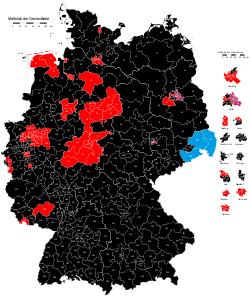

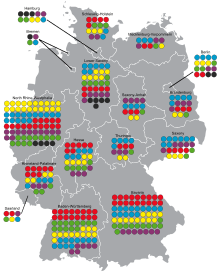

The left side shows constituency winners of the election by their party colours. The right side shows Party list winners of the election for the additional members by their party colours. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

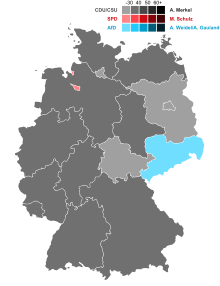

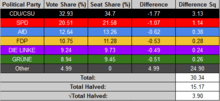

The Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), led by Chancellor Angela Merkel, won the highest percentage of the vote with 33%, though suffered a large swing against it of more than 8%. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) achieved its worst result since the Second World War with only 21% of the vote. Alternative for Germany (AfD)—which was previously unrepresented in the Bundestag—became the third party in the Bundestag with 12.6% of the vote, whilst the Free Democrats (FDP) won 10.7% of the vote and returned to the Bundestag after losing all their seats in the 2013 election. It was the first time since 1957 that a party to the right of the CDU/CSU Union gained seats in the Bundestag.

The other parties to achieve representation in the Bundestag were the Left and the Greens, who each won close to 9% of the vote. In the 709 member Bundestag, the CDU/CSU won 246 seats (200 CDU and 46 CSU), SPD 153, AfD 94, FDP 80, the Left (Linke) 69, and the Greens 67. A majority is 355.

For the second consecutive occasion, the CDU/CSU reached a coalition agreement with the SPD to form a grand coalition, the fourth in post-war German history. The new government took office on 14 March 2018. The agreement came after a failed attempt by the CDU/CSU to enter into a "Jamaica coalition" with the Greens and the Free Democrats, which the latter pulled out of citing irreconcilable differences between the parties on migration and energy policy.

Background

At the previous federal election in 2013, the incumbent government—composed of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the Christian Social Union (CSU), and the Free Democratic Party (FDP)—had failed to maintain a majority of seats. The FDP[1] failed to get over 5% of the vote in 2013, denying the party seats in the Bundestag for the first time in its history. In contrast, the CDU/CSU obtained their best result since 1990, with nearly 42% of the vote and just short of 50% of the seats. The CDU/CSU then successfully negotiated with the Social Democrats (SPD) to form a grand coalition for the third time.[2]

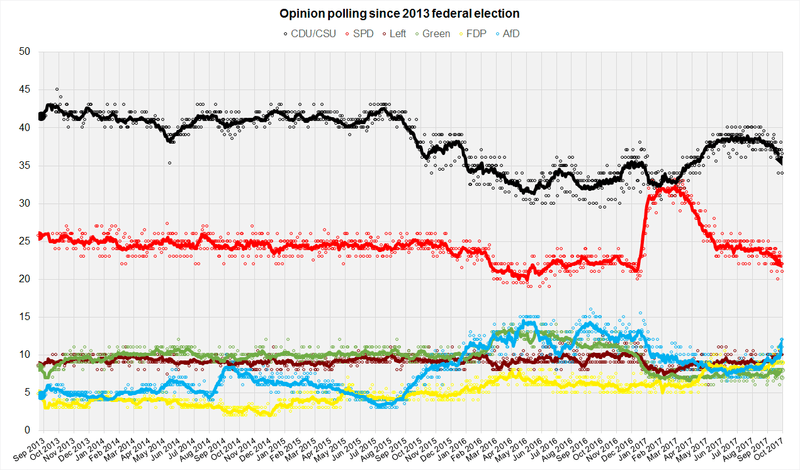

In March 2017, the SPD chose Martin Schulz, the former President of the European Parliament, as their leader and chancellor candidate. Support for the SPD initially increased; however, the CDU afterward regained its lead, with polls generally showing a 13–16% lead over the SPD.

Date

German law requires that a new Bundestag shall be elected on a Sunday or on a nationwide holiday between 46–48 months after the last Bundestag's first sitting (Basic Law Article 39 Section 1).[3] In January 2017, then-President Joachim Gauck scheduled the election for 24 September 2017.[4]

After the election, the 19th Bundestag had to hold its first sitting within 30 days. Until that first sitting, the members of the 18th Bundestag remained in office (Basic Law Article 39 Section 1 and 2).[3]

Electoral system

Germany uses the mixed-member proportional representation system, a system of proportional representation combined with elements of first-past-the-post voting. The Bundestag has 598 nominal members, elected for a four-year term; these seats are distributed between the sixteen German states in proportion to the states' population eligible to vote.

Every elector has two votes: a constituency and a list vote. 299 members are elected in single-member constituencies by first-past-the-post, based just on the first votes. The second votes are used to produce an overall proportional result in the states and then in the Bundestag. Seats are allocated using the Sainte-Laguë method. If a party wins fewer constituency seats in a state than its second votes would entitle it to, it receives additional seats from the relevant state list. Parties can file lists in each single state under certain conditions; for example, a fixed number of supporting signatures. Parties can receive second votes only in those states in which they have successfully filed a state list.

If a party by winning single-member constituencies in one state receives more seats than it would be entitled to according to its second vote share in that state (so-called overhang seats), the other parties receive compensation seats. Owing to this provision, the Bundestag usually has more than 598 members. The 18th Bundestag, for example, started with 631 seats: 598 regular and 33 overhang and compensation seats. Overhang seats are calculated at the state level, so many more seats are added to balance this out among the different states, adding more seats than would be needed to compensate for overhang at the national level in order to avoid negative vote weight.

In order to qualify for seats based on the party-list vote share, a party must either win three single-member constituencies or exceed a threshold of 5% of the second votes nationwide. If a party only wins one or two single-member constituencies and fails to get at least 5% of the second votes, it keeps the single-member seat(s), but other parties that accomplish at least one of the two threshold conditions receive compensation seats. (In the most recent example of this, during the 2002 election, the PDS won only 4.0% of the party-list votes nationwide, but won two constituencies in the state of Berlin.) The same applies if an independent candidate wins a single-member constituency (which has not happened since 1949). In the 2013 election, the FDP only won 4.8% of party-list votes; this cost it all of its seats in the Bundestag.

If a voter has cast a first vote for a successful independent candidate or a successful candidate whose party failed to qualify for proportional representation, their second vote does not count to determine proportional representation. However, it does count to determine whether the elected party has exceeded the 5% threshold.

Parties representing recognized national minorities (currently Danes, Frisians, Sorbs and Romani people) are exempt from the 5% threshold, but normally only run in state elections.[5]

Parties and leaders

Altogether 38 parties have managed to get on the ballot in at least one state and can therefore (theoretically) earn proportional representation in the Bundestag.[6] Furthermore, there are several independent candidates, running for a single-member constituency. The major parties that are likely to either exceed the threshold of 5% second votes or to win single-member constituencies (first votes) were:

| Name | Ideology | Leading candidate(s) |

2013 result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (%)[lower-alpha 8] | Seats | ||||||

| CDU/CSU | CDU | Christian Democratic Union of Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands |

Christian democracy | Angela Merkel | 34.1% | 311 / 631 | |

| CSU | Christian Social Union in Bavaria Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern |

Joachim Herrmann | 7.4% | ||||

| SPD | Social Democratic Party of Germany Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands |

Social democracy | Martin Schulz | 25.7% | 193 / 631 | ||

| Linke | The Left Die Linke |

Democratic socialism | Dietmar Bartsch Sahra Wagenknecht |

8.6% | 64 / 631 | ||

| Grüne | Alliance 90/The Greens Bündnis 90/Die Grünen |

Green politics | Cem Özdemir Katrin Göring-Eckardt |

8.4% | 63 / 631 | ||

| FDP | Free Democratic Party Freie Demokratische Partei |

Liberalism | Christian Lindner | 4.8% | 0 / 631 | ||

| AfD | Alternative for Germany Alternative für Deutschland |

National conservatism | Alexander Gauland Alice Weidel |

4.7% | 0 / 631 | ||

Traditionally, the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), which refer to each other as 'sister parties', do not compete against each other. The CSU only contests elections in Bavaria, while the CDU contests elections in the other fifteen states. Although these parties have some differences, such as the CSU's opposition to the previous government's immigration policies,[7] the CDU and CSU share the same basic political aims and are allowed by the Regulations of the Bundestag to join into one parliamentary Fraktion (a parliamentary group composed of at least 5% of the members of the Bundestag, entitled to specific rights in parliament) after the elections,[8] as they do in the form of the CDU/CSU group.

As the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) were likely to win the most seats in the election, their leading candidates are referred to as 'Chancellor candidates'. This does not, however, mean that the new Bundestag is legally bound to elect one of them as Chancellor.

Opinion polling

Results

The CDU/CSU and the SPD remained the two largest parties in the Bundestag, but both received a significantly lower proportion of the vote than they did in the 2013 election.

The AfD received enough votes to enter the Bundestag for the first time, taking 12.6 percent of the vote—more than double the five percent threshold required to qualify for full parliamentary status. It also won three constituency seats, which would have qualified it for proportionally-elected seats in any event.

The FDP returned to the Bundestag with 10.7 percent of the vote. Despite improving their results slightly and thus gaining a few more seats, the Left and the Greens remained the two smallest parties in parliament.

| ||||||||||||||

| Party | Constituency | Party list | Total seats |

+/– | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | |||||||||

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU)[lower-alpha 9] | 14,030,751 | 30.2 | 185 | 12,447,656 | 26.8 | 15 | 200 | −55 | ||||||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 11,429,231 | 24.6 | 59 | 9,539,381 | 20.5 | 94 | 153 | −40 | ||||||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD)[lower-alpha 10] | 5,317,499 | 11.5 | 3 | 5,878,115 | 12.6 | 91 | 94 | +94 | ||||||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 3,249,238 | 7.0 | 0 | 4,999,449 | 10.7 | 80 | 80 | +80 | ||||||

| The Left (DIE LINKE) | 3,966,637 | 8.6 | 5 | 4,297,270 | 9.2 | 64 | 69 | +5 | ||||||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (GRÜNE) | 3,717,922 | 8.0 | 1 | 4,158,400 | 8.9 | 66 | 67 | +4 | ||||||

| Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU)[lower-alpha 9] | 3,255,487 | 7.0 | 46 | 2,869,688 | 6.2 | 0 | 46 | −10 | ||||||

| Free Voters | 589,056 | 1.3 | 0 | 463,292 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Die PARTEI | 245,659 | 0.5 | 0 | 454,349 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Human Environment Animal Protection | 22,917 | 0.0 | 0 | 374,179 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| National Democratic Party | 45,169 | 0.1 | 0 | 176,020 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Pirate Party Germany | 93,196 | 0.2 | 0 | 173,476 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Ecological Democratic Party | 166,228 | 0.4 | 0 | 144,809 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Basic Income Alliance | – | – | – | 97,539 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| V-Partei³ | 1,201 | 0.0 | 0 | 64,073 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| German Centre | – | – | – | 63,203 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Democracy in Motion | – | – | – | 60,914 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Bavaria Party | 62,622 | 0.1 | 0 | 58,037 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| AD-DEMOCRATS | – | – | – | 41,251 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Animal Protection Alliance | 6,114 | 0.0 | 0 | 32,221 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Marxist–Leninist Party | 35,760 | 0.1 | 0 | 29,785 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Party for Health Research | 1,537 | 0.0 | 0 | 23,404 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| German Communist Party | 7,517 | 0.0 | 0 | 11,558 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Human World | 2,205 | 0.0 | 0 | 11,661 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| The Greys | 4,300 | 0.0 | 0 | 10,009 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Civil Rights Movement Solidarity | 15,960 | 0.0 | 0 | 6,693 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| The Humanists | – | – | – | 5,991 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Magdeburger Garden Party | 2,570 | 0.0 | 0 | 5,617 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Alliance for Germany | 6,316 | 0.0 | 0 | 9,631 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| The Urbans | 772 | 0.0 | 0 | 3,032 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| The Right | 1,142 | 0.0 | 0 | 2,054 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Socialist Equality Party | 903 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,291 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Bergpartei, die "ÜberPartei" | 672 | 0.0 | 0 | 911 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | New | ||||||

| Party of Reason | 242 | 0.0 | 0 | 533 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| The Violets | 2,176 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Alliance C – Christians for Germany | 1,717 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | New | ||||||

| New Liberals | 884 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | New | ||||||

| The Union | 371 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | New | ||||||

| Family Party | 506 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| The Women | 439 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | New | ||||||

| Renter's Party | 1,352 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | New | ||||||

| Others | 100,889 | 0.2 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | – | ||||||

| Independents | 2,458 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 586,726 | – | – | 460,849 | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Total | 46,976,341 | 100 | 299 | 46,976,341 | 100 | 410 | 709 | +78 | ||||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 61,688,485 | 76.2 | – | 61,688,485 | 76.2 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Source: Bundeswahlleiter | ||||||||||||||

Results by state

Second Vote ("Zweitstimme", or votes for party list) by state[9]

| State | Union | SPD | AfD | FDP | Linke | Grüne | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34.4 | 16.4 | 12.2 | 12.7 | 6.4 | 13.5 | 4.5 | |

| 38.8 | 15.3 | 12.4 | 10.2 | 6.1 | 9.8 | 7.5 | |

| 22.7 | 17.9 | 12.0 | 8.9 | 18.8 | 12.6 | 7.0 | |

| 26.7 | 17.6 | 20.2 | 7.1 | 17.2 | 5.0 | 6.3 | |

| 25.0 | 26.3 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 13.5 | 11.0 | 4.3 | |

| 27.2 | 23.5 | 7.8 | 10.8 | 12.2 | 13.9 | 4.5 | |

| 30.9 | 23.5 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 8.1 | 9.7 | 4.4 | |

| 33.1 | 15.1 | 18.6 | 6.2 | 17.8 | 4.3 | 4.9 | |

| 34.9 | 27.4 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 8.7 | 3.6 | |

| 32.6 | 26.0 | 9.4 | 13.1 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 3.8 | |

| 35.9 | 24.2 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 3.9 | |

| 32.4 | 27.2 | 10.1 | 7.6 | 12.9 | 6.0 | 3.9 | |

| 26.9 | 10.5 | 27.0 | 8.2 | 16.1 | 4.6 | 6.7 | |

| 30.3 | 15.2 | 19.6 | 7.8 | 17.8 | 3.7 | 5.7 | |

| 34.0 | 23.3 | 8.2 | 12.6 | 7.3 | 12.0 | 2.7 | |

| 28.8 | 13.2 | 22.7 | 7.8 | 16.9 | 4.1 | 6.5 |

Additional member seats by state

Second Vote ("Zweitstimme", or votes for party list) seats allocated by each of the 16 states by party.

| State[9] seats | CDU/CSU | SPD | AfD | FDP | LINKE | GRÜNE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16 | 11 | 12 | 6 | 13 | 58 | |

| 0 | 18 | 14 | 12 | 7 | 11 | 62 | |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 16 | |

| 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 15 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | |

| 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 28 | |

| 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 10 | |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 36 | |

| 4 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 12 | 12 | 78 | |

| 0 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 22 | |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 22 | |

| 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 14 | |

| 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 15 | |

| 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

Constitution of the 19th Bundestag

On 24 October 2017 the 19th Bundestag held its opening session, during which the Bundestag-members elected the Presidium of the Bundestag, i.e. the President and the Vice Presidents of the Bundestag. By tradition the biggest parliamentary group (in this case the CDU/CSU-group) has the right to propose a candidate for President of the Bundestag and following the rules of order every group has the right to be represented by at least one Vice President in the presidium. However, the Bundestag may decide to elect additional Vice Presidents. Every member of the presidium had to be elected by an absolute majority of the members of the Bundestag (in this case 355 votes). Until the election of the President of the Bundestag, the father of the house, the member of parliament with the longest membership, presided over the opening session.[10]

- Since he had been a member of the Bundestag for 45 years (since 1972), Wolfgang Schäuble would have been the father of the house.[11] However, since Schäuble was also a candidate for President of the Bundestag and would therefore likely have had to declare his own election, he refused the office. Hermann Otto Solms, who had been a member of the Bundestag for 33 years (1980–2013 and since 2017), stood in for him.[12][13]

- The CDU/CSU group proposed Wolfgang Schäuble to be President of the Bundestag.[14] Schäuble was elected on the first ballot (501 yes votes, 173 no votes, 30 abstentions, 1 invalid vote).

- The CDU/CSU group proposed Hans-Peter Friedrich to be a Vice President of the Bundestag.[15] Friedrich was elected on the first ballot (507 yes votes, 112 no votes, 82 abstentions, 2 invalid votes).

- The SPD group proposed Thomas Oppermann to be a Vice President of the Bundestag. Oppermann was elected on the first ballot (396 yes votes, 220 no votes, 81 abstentions, 6 invalid votes).

- The AfD group proposed Albrecht Glaser to be a Vice President of the Bundestag.[16] On 2 October 2017 the groups of the SPD, the FDP, The Left and Alliance 90/The Greens criticised the nomination because of controversial remarks about Islam and the basic right of religious freedom made by Glaser during the AfD's election campaign and asked the AfD group to nominate someone else to the post. The AfD group declined to accede to the request and nominate someone else.[17] Glaser failed to get a majority on three ballots, although even a plurality would have been sufficient on the third (first ballot: 115 yes votes, 550 no votes, 26 abstentions, 12 invalid votes, second ballot: 123 yes votes, 549 no votes, 24 abstentions, 1 invalid vote, third ballot: 114 yes votes, 545 no votes, 26 abstentions).

- The FDP group proposed Wolfgang Kubicki to be a Vice President of the Bundestag. Kubicki was elected on the first ballot (489 yes votes, 100 no votes, 111 abstentions, 3 invalid votes).

- The Left group proposed Petra Pau, who has held this position since 2006, to be a Vice President of the Bundestag. Pau was elected on the first ballot (456 yes votes, 187 no votes, 54 abstentions, 6 invalid votes).

- The Alliance 90/Greens group proposed Claudia Roth, who already held this position in the previous legislative session, to be a Vice President of the Bundestag.[18] Roth was elected on the first ballot (489 yes votes, 166 no votes, 45 abstentions, 3 invalid votes).

The AfD's seat in the Presidium has remained vacant since the first session. On 7 November 2018, the AfD-group nominated Mariana Harder-Kühnel to the post.[19] Harder-Kühnel failed to secure a majority on the first ballot on 29 November 2018 (223 yes votes, 387 no votes, 44 abstentions), on the second ballot on 12 December 2018 (241 yes votes, 377 no votes, 41 abstentions), or on the third ballot on 4 April 2019 (199 yes votes, 423 no votes, 43 abstentions)[20][21][22] On 9 April 2019, the AfD nominated Gerold Otten to the post; however, he has failed to secure a majority on the first ballot on 11 April 2019 (210 yes votes, 393 no votes, 31 abstentions),[23][24] on the second ballot on 16 May 2019 (205 yes votes, 399 no votes, 26 abstentions),[25] or on the third ballot on 6 June 2019 (211 yes votes, 426 no votes, 30 abstentions).[26]

Government formation

Jamaica Coalition

The SPD's leader and Chancellor candidate Martin Schulz and other party leaders stated that the SPD would not continue the current grand coalition government after unsatisfactory election results.[27] Following the SPD's announcement that it would return to the opposition, the media speculated that Chancellor Angela Merkel might need to form a Jamaica coalition (black-yellow-green) with the Free Democrats and the Greens as that was the only viable coalition without the AfD or The Left, both of which had been ruled out by Merkel as coalition partners before the election.[28] On 9 October 2017 Merkel officially announced that she would invite the Free Democrats and the Greens for talks about building a coalition government starting on 18 October 2017.[29][30]

In the final days of the preliminary talks, the four parties had still failed to come to agreement on migration and climate issues.[31] Preliminary talks between the parties collapsed on 20 November after the FDP withdrew, arguing that the talks had failed to produce a common vision or trust.[32]

Grand coalition

After the collapse of these coalition talks, the German President appealed to the SPD to change their hard stance and to consider a grand coalition with the CDU/CSU.[33] On 24 November, Schulz said he wants party members to be polled on whether to form another grand coalition with CDU/CSU after a meeting with President Frank-Walter Steinmeier the day before.[34] According to CDU deputy leader Julia Klöckner, talks were unlikely to begin until early 2018.[35] On 6 December the SPD held a party congress in which a majority of the 600 party delegates voted to start preliminary coalition talks with the CDU/CSU.[36] This decision was met with reluctance by the party's youth wing, which organised protests outside the convention hall.[37] Martin Schulz's backing of the coalition talks was interpreted by media organisations as a U-turn, as he had previously ruled out considering a grand coalition.[38][39][40]

On 12 January, the CDU/CSU and the SPD announced that they had reached a breakthrough in the preliminary talks and agreed upon an outline document to begin formal negotiations for the grand coalition.[41] On 21 January, the SPD held an extraordinary party conference of 642 delegates in Bonn.[42] The conference voted in favour of accepting the conclusion of preliminary talks and launching formal coalition negotiations with the CDU/CSU.[43] The formal coalition talks finally began on 26 January.[44][45]

On 7 February, the CDU/CSU and SPD announced that the final coalition agreement had been reached between the parties to form the next government.[46] According to terms of the agreement, the SPD received six ministries in the new government including the finance, foreign affairs and labour portfolios while the CDU received five and the CSU three ministries. The agreement stipulated there would be rises in public spending, an increase in German financing of the EU and a slightly stricter stance taken towards immigration.[47][48] SPD chairperson and Europe expert Martin Schulz was to step down as party leader and join the cabinet as foreign minister,[49] despite having previously stated that he would not serve under a Merkel-led government.[50] However, only days after these reports were published, Schulz renounced his plan to be foreign minister reacting on massive criticism by the party base.[51] The complete text of the coalition agreement was published on 7 February.[52] The coalition deal was subject to approval of the approximately 460,000 members of the SPD in a postal vote.[53][54] The results of the vote were announced on 4 March. In summary, 66% of respondents voted in favour of the deal and 34% voted against it.[55] Approximately 78% of the SPD membership responded to the postal vote.[55] The result allowed the new government to take office immediately following Bundestag approval of Merkel's fourth term on 14 March 2018.[56] This had been by far the longest government formation in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, as it was the first time a proposed coalition formation negotiation had collapsed and to be replaced by another coalition.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2017 Germany Bundestagswahl. |

- Ran in Frankfurt (Oder) - Oder - Spree (lost).

- Ran in Bodensee (lost).

- Ran in Rheinisch-Bergischer Kreis (lost).

- Ran in Rostock – Landkreis Rostock II (lost).

- Ran in Düsseldorf II (lost).

- Ran in Erfurt – Weimar – Weimarer Land II (lost).

- Ran in Stuttgart I (electoral district) (lost).

- Second votes (party list)

- The Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union of Bavaria call themselves sister parties. They do not compete against each other in the same states and they form one group within the Bundestag.

- Including Frauke Petry, who will not take the AfD whip or sit with the party.

References

- "Official German election results confirm Merkel's victory". Deutche Welle. Deutche Welle. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Bundesregierung: Die Große Koalition ist besiegelt" [The grand coalition (deal) is sealed]. Die Zeit (in German). 16 December 2013. ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Art 39 GG – Einzelnorm". Gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Bundespräsident Gauck fertigt Anordnung über Bundestagswahl aus". Bundespraesident.de. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Wahlsystem der Bundestagswahl in Deutschland – Wahlrecht und Besonderheiten". Wahlrecht.de. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "Bundestagswahl 2017 – Übersicht: Eingereichte und zugelassene Landeslisten der Parteien". Wahlrecht.de. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "Angela Merkel's Bavarian allies CSU threaten rightward shift". DW. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Deutscher Bundestag - IV. Fraktionen". Deutscher Bundestag.

- Officer, The Federal Returning. "Results - The Federal Returning Officer". www.bundeswahlleiter.de.

- "Deutscher Bundestag - Startseite". Deutscher Bundestag (in German). Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Braun, Stefan (25 September 2017). "Ein historisches Amt für Wolfgang Schäuble". sueddeutsche.de (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Müller, Volker. "Deutscher Bundestag - Wolfgang Schäuble mit Abstand dienstältester Abgeordneter". Deutscher Bundestag (in German). Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Sitzordnung im Bundestag noch umstritten". n-tv.de (in German). Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Böcking, David; Fischer, Sebastian (27 September 2017). "Künftiger Bundestagspräsident Schäuble: Der Alleskönner" – via Spiegel Online.

- "Hans-Peter Friedrich kandidiert zum Bundestags-Vizepräsidenten". inFranken.de (in German). Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Stichwahl in der Fraktion: AfD will Glaser als Bundestags-Vizepräsident". 27 September 2017 – via Spiegel Online.

- "Bundestagsvizepräsident: Widerstand gegen AfD-Vorschlag". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Neuer Bundestag: Die Grünen wollen Roth sehen". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "AfD nominiert Harder-Kühnel als Bundestags-Vize". tagesschau.de.

- "Deutscher Bundestag - Startseite". Deutscher Bundestag.

- Germany, Süddeutsche de GmbH, Munich. "Bundestag im zweiten Wahlgang gegen AfD-Abgeordnete". Süddeutsche.de.

- "AfD lawmaker Mariana Harder-Kühnel fails again in vice presidency bid | DW | 04.04.2019". DW.COM.

- Felten, Uwe. "Parlament soll Donnerstag abstimmen: Jetzt schickt die AfD Gerold Otten in die Wahl zum Bundestagsvize". RP ONLINE.

- "Deutschland: AfD scheitert auch mit Kandidat Otten bei Wahl zum Bundestagsvizepräsidenten". 11 April 2019 – via Die Zeit.

- "AfD-Kandidat scheitert bei Wahl zum Vize-Bundestagspräsidenten". NP - Neue Presse.

- "AfD-Politiker Gerold Otten scheitert auch im dritten Anlauf als Bundestagsvizepräsident". 6 June 2019 – via www.welt.de.

- Donahue, Patrick; Jennen, Birgit; Delfs, Arne (24 September 2017). "Merkel Humbled as Far-Right Surge Taints Her Fourth-Term Victory". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Andreas Rinke (29 August 2017). "Germany's Merkel rules out coalition with far left, far right". reuters.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Koalition: Merkel lädt ab Mittwoch kommender Woche zu Jamaika-Gesprächen". Spiegel Online. 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Paun, Carmen (7 October 2017). "Angela Merkel Ready to Move Forward with Jamaica Coalition". Politico. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Endspurt mit strittigen Themen". tagesschau. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "FDP bricht Jamaika-Sondierungen ab". tagesschau. 20 November 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "German coalition talks: Merkel and Schulz set to meet". DW. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Connolly, Kate (24 November 2017). "Germany's SPD is ready for talks to end coalition deadlock". The Guardian. Berlin. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Oltermann, Philip (27 November 2017). "German grand coalition talks unlikely to begin until new year". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "SPD agrees to open government talks with Merkel after Schulz pleads for green light". The Local Germany. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Escritt, Thomas. "German SPD backs talks with Merkel after impassioned Europe speech". Reuters. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Connolly, Kate. "Martin Schulz seeks backing for grand coalition to end Germany crisis". Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Charter, David. "Germany's 'grand coalition' could return as Schulz makes U-turn". Times. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Germany's SPD to join talks on resolving government impasse". Washington Post. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Knight, Ben. "German coalition talks reach breakthrough: A look at what comes next". DW. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Germany's Social Democrats vote for formal coalition talks with Angela Merkel". Economist. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Jones, Timothy; Martin, David. "Germany's SPD gives the go-ahead for coalition talks with Angela Merkel's CDU". DW. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "Germany: Angela Merkel's conservatives and SPD open grand coalition talks". DW. DeutscheWelle. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Thurau, Jens. "The major sticking points in Germany's upcoming coalition talks". DW. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Escritt, Thomas. "Few cheers at home for Germany's last-resort coalition". Reuters. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Chazan, Guy. "German conservatives smart at coalition concessions". Financial Times. FT. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- van der Made, Jan. "Europe, immigration key to Merkel's coalition deal with Social Democrats". Radio France Internationale. RFI. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Cole, Deborah. "Germany's top parties reach deal". Herald Live. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "Hero to 'loser': the broken promises of SPD leader Schulz". local.de. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "German coalition in crisis as Schulz ditches foreign minister plan". Politico Europe. 9 February 2018.

- "Ein neuer Aufbruch für Europa Eine neue Dynamik für Deutschland Ein neuer Zusammenhalt für unser Land" (PDF). cdu.de. CDU. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Knight, Ben. "Germany's Angela Merkel finally reaches coalition deal with SPD". DeutscheWelle. DW. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "Germany coalition deal reached after months of wrangling". BBC. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "Germany's Social Democrats endorse grand coalition". Politico Europe. 4 March 2018.

- "Bundestag reelects Merkel as chancellor". Politico Europe. 14 March 2018.

Further reading

- Dilling, M. 2018. “Two of the Same Kind? The Rise of the AfD and Its Implications for the CDU/CSU.” German Politics and Society 36 (1): 84–104

- Dostal, Jörg Michael. "The German Federal Election of 2017: How the wedge issue of refugees and migration took the shine off Chancellor Merkel and transformed the party system." Political Quarterly 88.4 (2017): 589-602. online

- Faas, Thorsten, and Tristan Klingelhöfer. "The more things change, the more they stay the same? The German federal election of 2017 and its consequences." West European Politics 42.4 (2019): 914-926.

- Franzmann, Simon T., Heiko Giebler, and Thomas Poguntke. "It’s no longer the economy, stupid! Issue yield at the 2017 German federal election." West European Politics 43.3 (2020): 610-638. online

- Hansen, Michael A., and Jonathan Olsen. "Flesh of the same flesh: A study of voters for the alternative for Germany (AfD) in the 2017 federal election." German Politics 28.1 (2019): 1-19. online

- Olsen, J. 2018. “The Left Party and the AfD. Populist Competitors in Eastern Germany.” German Politics and Society 36 (1): 70–83.

- Patton, D. 2017. “Monday, Monday: Eastern Protest Movements and German Party Politics since 1989.” German Politics 26 (4): 480–497.

- Schmidt, I. 2017. “PEGIDA: A Hybrid Form of a Populist Right Movement.” German Politics and Society 35 (4): 105–117.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)