1946 California's 12th congressional district election

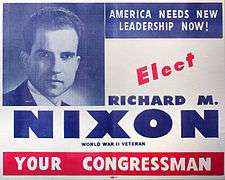

An election for a seat in the United States House of Representatives took place in California's 12th congressional district on November 5, 1946, the date set by law for the elections for the 80th United States Congress. In the 12th district election, the candidates were five-term incumbent Democrat Jerry Voorhis, Republican challenger Richard Nixon, and former congressman and Prohibition Party candidate John Hoeppel. Nixon was elected with 56% of the vote, starting him on the road that would, almost a quarter century later, lead to the presidency.

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

First elected to Congress in 1936, Voorhis had defeated lackluster Republican opposition four times in the then-rural Los Angeles County district to win re-election. For the 1946 election, Republicans sought a candidate who could unite the party and run a strong race against Voorhis in the Republican-leaning district. After failing to secure the candidacy of General George Patton, in November 1945 they settled on Lieutenant Commander Richard Nixon, who had lived in the district prior to his World War II service.

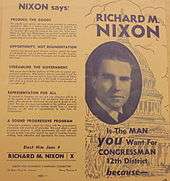

Nixon spent most of 1946 campaigning in the district, while Voorhis did not return from Washington D.C. until the end of August. Nixon's campaign worked hard to generate publicity in the district, while Voorhis, dealing with congressional business in the capital, received little newspaper coverage. Voorhis received the most votes in the June primary elections, but his percentage of the vote decreased from his share in the 1944 primaries. At five debates held across the district in September and October, Nixon was able to paint the incumbent as ineffectual and to suggest that Voorhis was connected to communist-linked organizations. Voorhis and his campaign were constantly on the defensive and were ineffective in rebutting Nixon's contentions. The challenger defeated Voorhis in the November general election.

Various explanations have been put forward for Nixon's victory, from national political trends to red-baiting on the part of the challenger. Some historians contend that Nixon received large amounts of funding from wealthy backers determined to defeat Voorhis, while others dismiss such allegations. These matters remain subjects of historical debate.

Background

District and campaigns

.jpg)

Since its creation following the 1930 census, the 12th district had been represented by Democrats. The 12th stretched from just south of Pasadena to the Orange and San Bernardino county lines, encompassing such small towns as Whittier, Pomona and Covina. The area has since been entirely absorbed into the Los Angeles megalopolis, but at the time it was principally agricultural. The freeway system had barely touched the 12th district; only a small segment of the Pasadena Freeway cut across its northwest corner.[1]

In 1932, John Hoeppel was elected to represent the 12th district. In 1936, Hoeppel was vulnerable as he had been convicted for trying to sell a nomination to West Point.[2] Voorhis defeated Hoeppel in the Democratic primary and easily won the general election.[1] Voorhis, who gained a reputation as a respected and hard-working representative,[3] nicknamed "Kid Atlas" by the press for taking the weight of the world on his shoulders, was loyal to the New Deal.[4]

The 12th district leaned Republican, the more so after 1941 when the Republican-dominated California State Legislature attempted to gerrymander Congressman Voorhis out of office by removing strong Democratic precincts in East Los Angeles from the district during the decennial redistricting.[5] The revamped 12th district had little industry and almost no union influence.[6] Voorhis was left with such Republican strongholds as San Marino, where he did not campaign, concluding that he would receive the same number of votes whether he visited there or not.[6] Despite the maneuvers of the Republicans in the legislature, Voorhis was re-elected in 1942, receiving 57% of the vote, and won with a similar percentage two years later.[5] Voorhis had not faced strong opposition prior to 1946. In his initial election, Voorhis benefited from the Roosevelt landslide of 1936. His 1938 opponent was so shy that Voorhis had to introduce him to the crowd at a joint appearance.[7] In 1940, he faced Captain Irwin Minger, a little-known commandant of a military school,[8] and his 1942 opponent, radio preacher and former Prohibition Party gubernatorial candidate Robert P. Shuler, "embarrassed GOP regulars".[7] In 1944, the 12th district Republicans were bitterly divided, and Voorhis easily triumphed.[7]

Republican search for a candidate

As Voorhis served his fifth term in the House, Republicans searched for a candidate capable of defeating him.[9] Local Republicans formed what became known as the "Committee of One Hundred" (officially, the "Candidate and Fact-Finding Committee") to select a candidate with broad support in advance of the June 1946 primary election.[10] This move caused some editorial concern in the district: The Alhambra Tribune and News, fearing the choice of a candidate was being taken away from voters in favor of a small group, editorialized that the committee formation was "a step in the wrong direction" and an attempt to "shove Tammany Hall tactics down our throats".[11]

The Committee initially wooed State Commissioner of Education (and former Whittier College president) Walter Dexter. Dexter was reluctant to give up his state post to run and sought a guarantee that he would receive another job if his candidacy failed. He continued to consider running for several months without reaching a decision, frustrating local Republicans. As Dexter dithered, Republicans tried to get General George Patton to run, though they were not certain if the general was a Republican.[10] However, a day after the Los Angeles Times speculated on the run, Patton announced from Germany his intent to "keep completely out of politics".[12] The Committee also contacted Stanley Barnes, a rising young Republican attorney and former football star at the University of California, Berkeley. Barnes declined to be considered, skeptical of the chances of defeating Voorhis.[12]

With little progress made on securing a high-profile candidate, Committee working groups held interviews. Of the eight men who applied, the most prominent was former congressman John Hoeppel, who promised to keep "the Jews and the niggers" out of the district.[2] On October 6, 1945, the Monrovia News Post reported that while Dexter seemed the likely candidate, "of course anything can happen in politics and generally does". The News Post stated that other names discussed by the Committee included "Lt. [sic] Richard Nixon, U.S.N.R., of Whittier."[13] Congressman Voorhis wrote his father and political adviser, Charles Voorhis, on October 15, "I understand the General has decided not to run in the 12th district. Dr. Dexter would, in my opinion, be hard to beat. But at least it would be a clean, decent campaign, and I'm not so sure I wouldn't prefer that even if I lost."[14] Herman Perry, Whittier Bank of America branch manager and Nixon family friend, wrote to Nixon, who was then a lieutenant commander in the Navy, telling him he should apply for the Committee's endorsement. Nixon replied enthusiastically. When Dexter finally turned the Committee down, he recommended Nixon, his onetime student.[10] Dexter died only days later of a heart attack, and Patton died in an auto accident before the 1946 campaign began.[10]

At the time, Nixon was stationed in Baltimore, Maryland, using his legal training to deal with military contract terminations. On November 1, 1945, he flew to California to meet influential Republicans and give a speech at a Committee meeting. The meeting was advertised throughout the district and was open to any potential candidate. However, the advertisements for the meeting noted that Nixon would be flying in to speak.[15] A number of potential rivals also showed up at the meeting on November 2, 1945, including a local judge and assemblyman. Nixon, who spoke last, was "electrifying", according to one Committee member.[16] When the Committee met to vote on November 28, Nixon received over two-thirds of the vote, which was then made unanimous. Committee chairman Roy Day immediately notified the victor of the Committee's endorsement.[17]

Nixon was already arranging to research Voorhis's record and to meet with Republican leaders in Washington, including House Minority Leader (and future Speaker) Joseph W. Martin, Jr. The newly minted candidate wrote to Day regarding Voorhis, "His 'conservative' reputation must be blasted. But my main efforts are being directed toward building up a positive, progressive group of speeches which tell what we want to do, not what the Democrats have failed to do ... I'm really hopped up over this deal, and I believe we can win."[18] However, "wheelhorse" Republicans deemed Nixon's campaign hopeless.[19] Nixon was a virtual unknown outside of his hometown of Whittier and was facing a popular and respected incumbent.[20] Charles Voorhis wrote his son that the Republicans had endorsed a Quaker named Richard Nixon, but hoped that his son would retain a large part of the Quaker vote. The elder Voorhis was confident that his son would triumph again, writing, "It is just another campaign that we have to go through ... In any event, we have nothing to worry about now."[21]

Primary campaign

Nixon was discharged from the Navy at the start of 1946. Within days, he and his wife Pat Nixon, the latter almost eight months pregnant, returned to Whittier. They initially moved in with the candidate's parents, Frank and Hannah. Nixon returned to his old law firm, but spent most of his time campaigning. Roy Day, chairman of the now-dissolved Committee, appointed himself as Nixon's campaign manager. This self-appointment dismayed the candidate somewhat, and Nixon unsuccessfully sought to replace Day.[22]

Voorhis had been in Washington since August 1945, attending to congressional business. He did not return to the district until August 1946, well after the June primary. By his own account, he was busy dealing with:

[The a]mendment of the Social Security Act, the Case Labor bill, the British loan, terminal leave pay for soldiers, and several appropriation bills [and] the most important problem our country had ever faced in all its history—the problem of what to do about atomic energy. I felt sure that the people of the district would rather have me stay on the job than come home to campaign.[23]

Beginning in February, the Republican hopeful began a heavy speaking schedule, addressing civic groups across the 400 square miles (1,000 km2) district.[24] Nixon's efforts to get publicity were aided by the birth of his daughter Tricia in late February. The new father was extensively interviewed and photographed with his infant daughter.[24] Congressman Voorhis's office sent the Nixons a government pamphlet entitled Infant Care, of which representatives received 150 per month to distribute to their constituents. When Richard Nixon sent his rival a note of thanks in early April, the congressman responded with a letter proposing that the two debate once Congress adjourned in August.[25]

In mid-March, Nixon was approached by former congressman Hoeppel,[26] who hated Voorhis.[27] Hoeppel offered to enter the Democratic primary in exchange for a payment of several hundred dollars plus the promise of a civil service job once the Republican was elected. After consulting with his aides, Nixon turned him down. Subsequently, Hoeppel filed as a Prohibition Party candidate. Voorhis was privy to these events through an informant close to the former representative, and was convinced that Roy Day had arranged to pay Hoeppel's filing fee. The congressman feared that Hoeppel would serve as a stalking horse for Nixon, sparing the Republican from any "mudslinging".[26] Voorhis responded to Hoeppel's filing with a letter to his campaign manager, Baldwin Park realtor Jack Long, stating that "it would be worthwhile for us to try our level best to beat him in the Prohibition primary by a write-in campaign".[28]

On March 18, two days before the filing deadline, Nixon filed in both the Republican and Democratic primaries under California's cross-filing system. Voorhis also filed in the two major party primaries. Under cross-filing, if the same candidate won both major party endorsements, he would be effectively elected, with only minor party candidates to stand against him. Day advanced the $200 (the current equivalent of $2,230[29]) for Nixon's filing fees, later noting that he had great difficulty being reimbursed.[30]

By late March, Nixon's stock speeches to civic groups were becoming worn. Day hired political consultant Murray Chotiner for $580 for the primary campaign, and the consultant warned that unless new life came into the campaign, it was in serious danger.[31] In the following years, Chotiner was to become Nixon's campaign manager, adviser, and friend in an association that lasted until Chotiner's death a few months before President Nixon's 1974 resignation.[32]

Chotiner arranged for stories in local papers alleging that Voorhis had been endorsed by "the PAC", hoping that voters would take that to mean the Congress of Industrial Organizations's Political Action Committee (CIO-PAC). The CIO was a labor federation which later merged with the American Federation of Labor to form the AFL-CIO. It had been organized in 1943 and took left-wing stands; its PAC was seen as a communist front organization by some. A second PAC, the National Citizen's Political Action Committee (NCPAC) was also affiliated with the CIO, but was open to those outside the labor movement. Among the 1946 members of the NCPAC were actors Melvyn Douglas and Ronald Reagan.[33] Both PACs had been headed by the late labor leader, Sidney Hillman, and the two organizations shared office space in New York City.[34] While the CIO's national leadership decried communism; some of the local CIO-PAC branches were dominated by Communist Party members.[35] The CIO-PAC, which had endorsed Voorhis in 1944, refused to back him again. The Southern California chapter of the NCPAC endorsed Voorhis on April 1, 1946. Chotiner's strategy was to conflate the two PACs in the public eye.[33]

Nourished by the PAC controversy, the Republican campaign gained new life as Nixon returned to the lecture circuit. After Nixon spoke to a Lions Club meeting on May 1, a worried Voorhis supporter wrote to the congressman, "He carried the group by storm. He is dangerous. You will have the fight of your life to beat him."[36]

The primary was held on June 4, 1946. Both Voorhis and Nixon won his own party's primary, with Voorhis garnering a considerable number of votes in the Republican poll. When all the votes from all primaries were added together, Voorhis outpolled Nixon by 7,000 votes. Voorhis's total percentage of the vote decreased from 60% in the 1944 primaries to 53.5% in 1946.[37] Hoeppel survived the write-in campaign to advance to the general election.[38]

General election

Following a two-week vacation in British Columbia after the primary, Nixon returned to the 12th district. The Republican began the general election campaign by replacing Roy Day with South Pasadena engineer Harrison McCall as campaign manager. As Chotiner was increasingly distracted by his position as Southern California campaign manager for the (successful) reelection bid of Republican Senator William Knowland, the Nixon campaign added publicist William Arnold.[39] Voorhis, on the other hand, remained in Washington, dealing with Congressional business and generating little publicity. He corresponded with his father and with his campaign manager, Jack Long, by letter.[40] Voorhis hoped to return to California in mid-August but while returning from Washington in August, he was forced to have surgery for hemorrhoids in Ogden, Utah.[41] Voorhis spent two weeks in an Ogden hotel recuperating from the operation[42] and did not return to the district until the end of August. Voorhis wrote later, "I can't say I was exactly 'ready for the fray'. But the 'fray' was certainly ready for me."[43]

South Pasadena debate

Nixon did not reply to Voorhis's April debate proposal. In May, the congressman wrote to Long as Nixon's campaign initially made the alleged PAC endorsement an issue. Voorhis suggested that Nixon be challenged to debates as a matter of urgency. Long responded in June, saying that though Nixon was known as a champion debater during his Whittier College days, "with your age and experience the general public might not take kindly to your challenging a boy like Nixon".[39] Long advised awaiting a challenge from Nixon. By August, the two campaigns had settled on a debate to be held before a veteran's group in Whittier on September 20.[39] However, the "Independent Voters of South Pasadena" (IVSP), headed by future Voorhis biographer Paul Bullock,[44] announced a September 13 town meeting on campaign issues at South Pasadena Junior High School. The IVSP's actual purpose in having the meeting was to get a vulnerable Republican assemblyman (who declined his invitation) to debate his Democratic rival, but Senate and 12th district Republican and Democratic candidates were invited. Given that the debate sponsors were liberals, some of Nixon's aides advised him to refuse, but he overrode them. Voorhis also accepted; when it was suggested to him later he should have sent a spokesman, he responded, "I suppose so, but I just couldn't bring myself to refuse."[39] Both Senate candidates declined their invitations, with Senator Knowland sending Chotiner in his place, while Democratic candidate Will Rogers, Jr. sent Representative Chester E. Holifield of the neighboring 19th district.[39]

.jpg)

The town meeting attracted a packed crowd of over a thousand, with Nixon supporters distributing anti-Voorhis literature at the door. The Senate proxies spoke first for their candidates, followed by Voorhis. Nixon, who had notified organizers that he would be late due to another commitment, arrived during Voorhis's speech, and remained backstage until the congressman had completed his talk. He then came onstage, shook hands with Voorhis, and delivered a fifteen-minute address. A question-and-answer period then followed, with a Nixon supporter asking Voorhis about his onetime Socialist registration, and about his views on monetary policy.[45] After the representative responded, a Voorhis supporter asked Nixon why he was making "false charges" about the supposed Voorhis CIO-PAC endorsement.[45] In response, Nixon reached into his pocket and pulled out a copy of a Southern California NCPAC bulletin mentioning the group's endorsement of Voorhis.[45] The congressman was unaware of the endorsement; those of his aides in the know had "completely forgotten" to tell him.[46] Nixon walked halfway across the stage and displayed it to Voorhis, asking him to read it for himself. Voorhis came from his seat and took it,[45] and (according to Bullock, who served as timekeeper at the debate) "mumbled" that this seemed to be a different organization from the CIO-PAC.[46] Nixon reclaimed the document, and began to read out names of the members of the boards of directors of the two groups, "It's the same thing, virtually, when they have the same directors."[45] The crowd began to cheer Nixon, who later wrote, "I could tell by the audience reaction that I had made my point", and to jeer Voorhis, who wrote, "They'd boo and laugh at my remarks, and this disturbed me."[45]

In the midst of the turmoil, Prohibition Party candidate Hoeppel came down the aisle (according to Bullock, possibly drunk)[46] and demanded to know why he had been excluded from the debate. He was permitted to ask one question, of Voorhis, and the evening ended. According to Bullock, "the magnitude of Nixon's triumph did not immediately dawn on us."[46] Congressman Holifield had grasped it, and when Voorhis asked him, "How did it go?" he responded, "Jerry, he cut you to pieces."[45]

Additional debates

On September 19, Voorhis wired the NCPAC's Los Angeles and New York offices, requesting that "whatever qualified endorsement the Citizens PAC may have given me be withdrawn".[47] By this time, newspapers across the district had printed Nixon's charges, along with a Nixon advertisement castigating Voorhis for allegedly accusing Nixon of lying about the PAC endorsement.[47] According to Nixon biographer Roger Morris, the repudiation of NCPAC endorsements did not help Voorhis, as his actions "would seem to many a half-guilty shedding of sinister backing he never had. To the end, as Chotiner had calculated, the PACs were hopelessly entangled."[47] The Nixon campaign distributed 25,000 thimbles[19] labeled "Nixon for Congress/Put the needle in the P.A.C."[48]

The second debate was held at Patriotic Hall in Whittier on September 20. As the debate was sponsored by the Whittier Ex-Servicemen's Association, attendance was limited to veterans.[49] The candidates debated the best way of dealing with the postwar housing shortage. Voorhis favored restricting building of commercial structures to free up materials for housing, while Nixon urged the removal of all building restrictions.[49] When Nixon repeated his PAC allegations, Voorhis noted his request to the NCPAC, stating that he could not be held responsible for its actions. According to Morris, the debate ended as a draw, or perhaps even a Voorhis victory.[47] Chotiner convinced Nixon that he needed to run an aggressive campaign to the end, and McCall challenged the Voorhis campaign to as many as eight additional debates, of which three were actually held.[47]

The debates captured the interest of the public in the district and attracted large crowds. The candidates were compared to Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, who had famously debated in their 1858 senatorial campaign, and bands played marches as each candidate entered the venue.[49] The two candidates' third meeting was held at Bridges Auditorium in Claremont on October 11. Voorhis was, by his own admission, "awfully tired".[50] The candidates discussed labor policy, and Nixon "scored" by detailing a policy for dealing with public strikes that Voorhis too late realized was taken from a bill he had drafted.[50] Nixon took Voorhis aside after the debate and lambasted him for addressing him as "Lieutenant Commander Nixon", accusing him of pandering to former enlisted men's dislike of officers.[50]

In the fourth debate, on October 23 at Monrovia High School, Nixon attacked Voorhis' congressional record. The challenger alleged that in the previous four years, Voorhis only had been able to pass a single bill through Congress and into law. The bill in question transferred jurisdiction over rabbit farming from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture.[51] Nixon chided, "One has to be a rabbit to get effective representation in this congressional district."[lower-alpha 1] Voorhis responded that he had sponsored an act to employ the physically handicapped, but Nixon stated that it was not a law, but a joint resolution.[51] Nixon restated his allegation regarding Voorhis and the PAC; Voorhis retorted that he had repudiated the NCPAC endorsement. Nixon parried with a comment that Voorhis's voting record "earned him the endorsement, whether he wanted it or not".[52] Nixon also contended that in 46 votes, Voorhis had almost entirely followed the CIO-PAC agenda. Distraught, Voorhis stayed up until 4 am studying the votes Nixon had taxed him with. He concluded that due to duplications, there were actually only 27 roll calls in question, on many of which he had opposed the CIO-PAC position. The congressman also found that the votes "friendly" to the CIO-PAC included one authorizing a school lunch program.[53]

The final debate took place October 28 at the San Gabriel Civic Auditorium, to an overflow crowd in excess of a thousand. Voorhis went on the attack, charging Nixon with misrepresenting the "46 votes" to avoid real debate and any discussion of where Nixon himself stood on issues.[54] The Republican candidate stated that he was fighting for "the person on a pension trying to keep up with the rising cost of living ... the white-collar worker who has not had a raise ... Americans have had enough, and they have come to the conclusion that they are going to do something."[55] Nixon sat down to thunderous applause, and the San Gabriel Sun described Voorhis: "He pauses, breathes heavily, scans the audience with tired eyes, adjusts his glasses nervously with both hands, and then strikes the podium with an open hand."[55]

Final days

In mid October, the Nixon campaign unveiled an advertisement which foreshadowed his run for Senate four years later. After stating that Nixon, at the South Pasadena debate, confronted the congressman with "a photostatic copy of his endorsement by the communist-dominated PAC", the ad stated, "Among the extreme left-wingers with whom Voorhis kept company in voting the PAC line are Helen Gahagan Douglas, Vito Marcantonio ..."[56] On October 29, the Alhambra Post-Advocate and Monrovia News-Post printed identical pieces entitled "How Jerry and Vito voted", comparing the California congressman's voting record with that of Marcantonio, a leftist New York congressman. In 1950, a similar comparison between the voting record of Marcantonio and Democratic Senate nominee Douglas, printed on pink paper, came to be known as the "Pink Sheet".[55]

The Nixon campaign continued to run newspaper ads touching on the PAC issue. One ad suggested Radio Moscow had urged the election of the CIO slate. Others touched on Voorhis's past registration as a Socialist, and stated that his congressional record "is more Socialistic and Communistic than Democratic".[53] The Democrats brought James Roosevelt and other prominent Democrats into the district to campaign for Voorhis.[53] Nixon proposed that his wartime acquaintance, former Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen campaign for him. However, the candidate could not get permission from the California Republican committee for Stassen to visit.[57] Voorhis publicized a letter he had received from the Republican governor, Earl Warren, praising him for a disability insurance proposal he had made. Nixon supporters asked Warren for a letter praising Nixon, or at least a retraction of the Voorhis letter. Warren refused, saying that Voorhis deserved the compliment, and Nixon would not receive an endorsement. This conflict began a contentious relationship between Nixon and Warren which lasted until Warren's death shortly before Nixon's resignation as president.[58]

No polls had been taken during the campaign.[59] On election night, Voorhis took an early lead in the vote count, but was soon overtaken by his challenger, whose margin increased as the night went on. Nixon defeated Voorhis by over 15,000 votes. The Republican won 19 of the 22 municipalities in the district, including Voorhis's home town of San Dimas. Voorhis won the Democratic strongholds of El Monte and Monterey Park, as well as rural Baldwin Park.[58] Time magazine's post-election issue came out in mid-November, and it praised the future president for "politely avoid[ing] personal attacks on his opponent".[19]

Aftermath and analysis

Candidates

The day after the election, Voorhis issued a concession statement, wishing Nixon well in his new position, and stating:

I have given the best years of my life to serving this district in Congress. By the will of the people that work is ended. I have no regrets about the record I have written. I know the principles I have stood for and the measures I have fought for are right. I know, too, that, in broad outline at least, they are vital to the future safety and welfare of our country. I know the day will come when a lot more people will recognize this than was the case on November fifth.[60]

Former congressman Hoeppel, who gathered just over one percent of the vote, wrote Nixon after the election, stating that he had never expected to win, and that his purpose had been "to expose what I considered to be the alien-minded, un-American, PAC, Red, congressional record of the Democratic incumbent".[61] Despite any hard feelings, Voorhis sent Nixon a letter of congratulations in early December 1946. Nixon and Voorhis met for an hour at Voorhis's office, and parted, according to Voorhis, as friends.[62] In 1971, Voorhis said that the two had never spoken again.[63] Voorhis's final letter as a congressman, written on December 31, was to his father, who had been his political adviser throughout his congressional career. Representative Voorhis wrote, "It has been primarily due to your help, your confidence, your advice ... above all to a feeling I have always had that your hand was on my shoulder. Thanks ... God bless you."[62]

Voorhis never ran again for political office, working as an executive in the cooperative movement for twenty years after his defeat.[64] Hoeppel continued as publisher and editor of National Defense magazine, a publication for veterans, until his 1960 retirement, and died in Arcadia in 1976 at age 95.[65][66] Nixon served two terms in the House, and in 1950 was elected to the United States Senate, continuing his political rise, which would lead him to the White House in 1969.[67]

Historical issues

The 12th district race of 1946 was little noticed at the time.[68] As Nixon became prominent, the 1946 race was scrutinized more closely. Nixon biographer Herbert Parmet noted, "Except for Nixon's subsequent reputation, what happened in California's Twelfth would have been indistinguishable from campaigns across the country to elect the Eightieth Congress."[69] Jonathan Aitken, also a biographer of Nixon, attributes the later scrutiny to "the unexpected toppling of a liberal icon and [the Democratic Party's] regret over the meteoric rise of the new Republican hero who won the seat".[68]

Nixon's defeat of Voorhis has been cited as the first of a number of red-baiting campaigns by the future president which elevated him to the House, the Senate, the Vice Presidency, and eventually put him in position to run for president.[70] Nixon, in his 1978 memoir, stated that the central issue in the 1946 campaign was "the quality of life in postwar America",[3] and he won because voters "had 'had enough,' and they decided to do something about it".[71] Voorhis, in his 1947 memoir, indicated that the "most important single factor in the campaign of 1946 was the difference in general attitude between the 'outs' and the 'ins'. Anyone seeking to unseat an incumbent needed only to point out all the things that had gone wrong and all the trouble of the war period and its aftermath."[72]

In later years, Voorhis had more to say about the reasons for his defeat.[73] In 1958, he alleged that voters had received anonymous phone calls saying that he was a communist, that newspapers had stated that he was a fellow traveler, and that when Nixon got angry, he would "do anything".[73] In November 1962, after Nixon's defeat in the California gubernatorial race, Voorhis appeared on Howard K. Smith's News and Comment program on ABC in the episode entitled "The Political Obituary of Richard M. Nixon" and complained about the way Nixon had conducted himself in the 1946 race. Voorhis's appearance was overshadowed by the controversial participation of Nixon adversary Alger Hiss.[74] In 1972, Voorhis authored a book, The Strange Case of Richard Milhous Nixon, in which he stated that Nixon was "quite a ruthless opponent" whose "one cardinal and unbreakable rule of conduct" was "to win, whatever it takes to do it".[75] In 1981, three years before his death, Voorhis denied in an interview that he had been endorsed by the NCPAC.[76]

In his memoirs, Voorhis alleged that in October 1945, "a representative of a large New York financial house" journeyed to California to meet with a number of influential Californians and "bawl them out" for allowing Voorhis, whom the New Yorker supposedly described as "one of the most dangerous men in Washington", to remain in Congress.[72] In an early draft of his memoir, Voorhis wrote that he had documentation showing that "the Nixon campaign was a creature of big eastern financial interests".[76] Nixon biographer Roger Morris suggested that the amount the Nixon campaign reported "was only a small fraction of what actually went into the campaign."[77] According to Morris, the Committee of One Hundred represented wealthy interests, and Nixon benefited from "the University Club ... the corporate levies, the vastly larger forces arrayed against Voorhis".[78] Nixon himself addressed this point in his memoir:

As I moved up the political ladder, my adversaries tried to picture me as the hand-picked stooge of oil magnates, rich bankers, real estate tycoons and conservative millionaires. But a look at the list of my early supporters shows that they were typical representatives of the Southern California middle class: an auto dealer, a bank manager, a printing salesman, and a furniture dealer.[71]

Nixon biographer Irwin Gellman, writing in 1999, nine years after Morris, disagreed with the latter's conclusions. Gellman argued that the Committee was a "grassroots" group which was "far from sophisticated" in its efforts to find a candidate.[79] Parmet wrote that the campaign was not well financed, "Nixon had to learn that money would be scarce until he became a winner ... The Nixon campaign of 1946 did look like a shoestring affair."[80] Aitken points out that Nixon spent no money on radio advertising during the campaign.[68]

Other allegations center on Murray Chotiner, painting him as the evil genius of the campaign.[79] Voorhis, for example, in his 1972 book, deemed himself "the first victim of the Nixon-Chotiner formula for political success."[75] Several writers, including Kenneth Kurz in his book, Nixon's Enemies,[81] and Ingrid Scobie in her biography of Helen Douglas, Center Stage,[82] describe Chotiner incorrectly as Nixon's 1946 campaign manager. Part of this inflation is due to Chotiner himself, who, in later years, lost no opportunity to exaggerate his role in the 1946 race, to the annoyance of Day and McCall.[79] According to Nixon biographer Stephen Ambrose, "Nevertheless, the legend grew. In the eyes of Nixon's critics, as a candidate he was merely a front man for Chotiner's evil manipulations. But it simply was not so."[83]

A number of biographies on Nixon or Voorhis, or which otherwise touch on the 1946 campaign, state with varying degrees of certainty that during the final weekend of the campaign, anonymous calls were made to district households. The caller would ask "Did you know Jerry Voorhis is a communist?" and then hang up.[84][85] According to Bullock, there was a phone bank staffed by workers who had responded to a newspaper ad, run by the Nixon organization in Alhambra. Bullock cites as his source for this Zita Remley, a "Voorhis admirer", who stated that her niece had worked there.[lower-alpha 2][85] Although the niece died before Bullock's book was written, according to Bullock, Remley's "reputation for veracity is unchallengeable".[85]

Campaigns

Nixon spent most of 1946 campaigning in the district, and worked hard to extend his name recognition beyond his hometown of Whittier.[86] In 1952, as Nixon ran for vice president, the Madera News-Tribune set forth its view of why Nixon beat Voorhis, "He rang doorbells, he talked on street corners and in auditoriums, he kissed babies, patted old ladies on the cheek, and otherwise made himself known wherever and whenever two people would stop and listen to him. He made friends with the press and radio, he went out of his way to be congenial and likable."[87] Bullock indicated that regardless of the tactics used, Nixon would likely have beaten the incumbent given the national Republican tide that swept the party into power in the House of Representatives for the first time since 1931.[lower-alpha 3]

Starting in the primary, the Nixon campaign made determined efforts to woo the district's newspapers. The campaign targeted smaller papers, especially the small weekly newspapers that were distributed for free; Republican surveys found that these were widely read and trusted.[88] Nixon supporter and Republican National Committeeman from California McIntyre Faries arranged to buy ads on behalf of the Nixon campaign on condition that the newspaper run an editorial at its direction (most of the papers were, in any event, Republican in their outlook).[88] These efforts paid off; 26 of the 30 newspapers serving the district endorsed Nixon.[89] According to Nixon biographer Morris, Voorhis was given no coverage in newspapers, or limited to small paid advertisements. The paper owners told the Voorhis campaign that, with the postwar paper shortage, space had to be saved for regular customers.[90]

Voorhis's campaign, described by Bullock as "traditionally amateurish and poorly put together",[91] was slow to perceive the threat presented by Nixon[92] and remained continually on the defensive.[93] In 1971, in an article marking the 25th anniversary of the campaign, Voorhis acknowledged that "I never had much of an organization; frankly, there was no form to it. And we needed it badly in 1946."[63] In the same article, the Los Angeles Times described Voorhis's campaign as "undermanned, underfinanced, outgunned, outmaneuvered and he apparently was on the wrong side of most of the issues of the day".[63] His one avenue of outreach in the press was his newspaper column, People's Business, which ran in most local newspapers. In July 1946, Voorhis chose to suspend this column lest it be thought that he was using it as a means of campaigning. According to Gellman, this weakened Voorhis's political outreach.[94]

One blunder identified by Gellman was Voorhis's decision to debate Nixon, as it raised the challenger's profile to the same level as the incumbent's.[87] This decision was described by Morris as "quiet hubris".[76] Nixon later stated, "In 1946, a damn fool incumbent named Jerry Voorhis debated a young unknown lawyer, and it cost him the election."[lower-alpha 4] Gellman itemized Voorhis's other errors: "He never established a viable Democratic organization; instead he relied on his father and friends to evaluate voters' likely habits. Rather than return to campaign in the primary when he recognized Nixon's attractiveness, he remained in the capital, allowing Nixon to court newspaper publishers and reporters as well as constituents who wanted to have firsthand contact with their congressional representative. Even when Voorhis returned to the district, he made one blunder after another."[92]

Ambrose summed up his chapter on the 1946 campaign:

For Whittier and the 12th district, Nixon's first campaign produced the first Nixon haters and the first group of Nixon supporters. This was a consequence of his campaigning style and his penchant for polarizing his constituents over basic issues. The numbers of both groups would grow in the years ahead, until virtually everyone in the nation belonged to either one or the other.[95]

Results

General election, November 5, 1946

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Richard Nixon | 65,586 | 56.02 | |||

| Democratic | Jerry Voorhis (incumbent) | 49,994 | 42.70 | |||

| Prohibition | John Hoeppel | 1,476 | 1.26 | |||

| Total votes | 117,069 | 100.0 | ||||

| Republican gain from Democratic | ||||||

Party primaries, June 4, 1946

Hometowns in parentheses, as is any other relevant information.

Democratic

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jerry Voorhis (incumbent, San Dimas) | 25,048 | 79.96 | |

| Richard Nixon (Whittier) | 5,077 | 16.21 | |

| William Kinnett (Monterey Park) | 1,200 | 3.83 | |

| Total votes | 31,325 | 100.00 | |

Republican

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard Nixon | 24,397 | 64.09 | |

| Jerry Voorhis | 12,125 | 31.85 | |

| William Kinnett | 1,532 | 4.02 | |

| Total votes | 38,064 | 100.00 | |

Prohibition

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Hoeppel (Alhambra) | 139 | 60.43 | |

| Jerry Voorhis (write in) | 91 | 39.57 | |

| Total votes | 230 | 100.00 | |

Notes

Explanatory notes

- Morris 1990, p. 328. Some sources attribute this discussion to the fifth debate.

- Helen Douglas, in her memoir, A Full Life, mentions a Zita Remley as a paid staffer who put together a pamphlet for her, Catholics for Douglas. Douglas 1982, p. 323

- Bullock 1978, p. 278. The Republicans kept a narrow majority in the House in the 1930 elections but lost it due to deaths, resignations, and subsequent special elections before the House convened in December 1931.

- Morris 1990, pp. 335–36. Nixon stated this at a 1960 campaign staff meeting when he indicated his opposition to debating John Kennedy, some weeks before he agreed to do so. Halberstam 1979, pp. 328–29.

Citations

- Morris 1990, p. 286.

- Parmet 1990, pp. 92–93.

- Nixon 1978, p. 41.

- Morris 1990, pp. 258–259.

- Mazo 1959, p. 43.

- Morris 1990, p. 287.

- Gellman 1999, pp. 27–28.

- Bullock 1978, p. 148.

- Fowler & 1984-09-12.

- Parmet 1990, pp. 91–92.

- Alhambra Tribune and News & 1945-10-18.

- Morris 1990, p. 273.

- Monrovia News Post & 1945-10-06.

- Voorhis & 1945-10-15.

- Morris 1990, p. 276.

- Morris 1990, pp. 280–281.

- Morris 1990, p. 282.

- Mazo 1959, p. 44.

- Time & 1946-11-18.

- Bullock 1978, pp. 243–244.

- Gellman 1999, p. 40.

- Morris 1990, p. 285.

- Voorhis 1947, p. 332.

- Gellman 1999, pp. 43–44.

- Gellman 1999, p. 47.

- Morris 1990, p. 291.

- Bullock 1978, p. 116.

- Voorhis & 1946-03-27.

- MeasuringWorth.

- Gellman 1999, p. 45.

- Morris 1990, pp. 291–292.

- Lydon & 1974-01-31.

- Morris 1990, pp. 293–294.

- Bochin 1990, p. 15.

- Gellman 1999, p. 52.

- Morris 1990, p. 294.

- Mazo 1959, p. 45.

- Jordan 1946, p. 17.

- Morris 1990, pp. 315–316.

- Morris 1990, pp. 304–305.

- Gellman 1999, p. 67.

- Morris 1990, p. 305.

- Voorhis 1947, p. 333.

- Gellman 1999, p. 69.

- Morris 1990, pp. 318–319.

- Bullock 1978, pp. 260–262.

- Morris 1990, pp. 320–321.

- Morris 1990, p. 314.

- Bochin 1990, p. 18.

- Morris 1990, p. 327.

- Gellman 1999, p. 78.

- Ambrose 1988, p. 134.

- Gellman 1999, p. 79.

- Gellman 1999, pp. 80–81.

- Morris 1990, p. 331.

- Morris 1990, p. 325.

- Gellman 1999, p. 75.

- Gellman 1999, pp. 75–77.

- Nixon 1978, p. 40.

- Voorhis 1947, pp. 346–347.

- Gellman 1999, pp. 82–83.

- Gellman 1999, p. 84.

- Seelye & 1971-07-21.

- Bioguide, Voorhis.

- Bioguide, Hoeppel.

- The Los Angeles Times & 1976-09-22.

- Bioguide, Nixon.

- Aitken 1993, p. 130.

- Parmet 1990, p. 97.

- Voorhis 1972, p. 23.

- Nixon 1978, p. 42.

- Voorhis 1947, p. 334.

- Gellman 1999, p. 85.

- Ambrose 1988, p. 673.

- Voorhis 1972, p. 9.

- Morris 1990, p. 336.

- Morris 1990, p. 337.

- Morris 1990, p. 335.

- Gellman 1999, p. 87.

- Parmet 1990, p. 102.

- Kurz 1998, p. 49.

- Scobie 1992, p. 245.

- Ambrose 1988, p. 125.

- Morris 1990, p. 332.

- Bullock 1978, p. 277.

- Ambrose 1988, p. 122.

- Gellman 1999, p. 452.

- Morris 1990, p. 296.

- Aitken 1993, p. 125.

- Morris 1990, p. 297.

- Bullock 1978, p. 268.

- Gellman 1999, p. 88.

- Morris 1990, p. 322.

- Gellman 1999, p. 68.

- Ambrose 1988, p. 140.

- Graf 1947, p. 3.

References

- Aitken, Jonathan (1993). Nixon: A Life. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-489-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ambrose, Stephen (1988). Nixon: The Education of a Politician, 1913–1962. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-65722-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bochin, Hal (1990). Richard Nixon: Rhetorical Strategist. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26108-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bullock, Paul (1978). Jerry Voorhis: The Idealist as Politician. Vantage Press. ISBN 978-0-533-03120-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Douglas, Helen Gahagan (1982). A Full Life. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-11045-7. OCLC 7796719.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gellman, Irwin (1999). The Contender. The Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4165-7255-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halberstam, David (1979). The Powers That Be. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-252-06941-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurz, Kenneth (1998). Nixon's Enemies. Lowell House. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7373-0000-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mazo, Earl (1959). Richard Nixon: A Political and Personal Portrait. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morris, Roger (1990). Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of an American Politician. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-1834-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nixon, Richard (1978). RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. New York, NY: Grosset and Dunlop. ISBN 978-0-671-70741-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parmet, Herbert (1990). Richard Nixon and His America. Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-082-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scobie, Ingrid (1992). Center Stage: Helen Gahagan Douglas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506896-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Voorhis, Jerry (1947). Confessions of a Congressman. The Country Life Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Voorhis, Jerry (1972). The Strange Case of Richard Milhous Nixon. Popular Library. ISBN 978-0-8397-7917-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Other sources

- "A step in the wrong direction". Alhambra Tribune and News. 1945-10-18. p. 8.

- "Hoeppel, John Henry". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- "Nixon, Richard Milhous". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- "Voorhis, Horace Jeremiah (Jerry)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- Graf, William (1947). "Statistics of the Congressional Election of November 5, 1946" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. p. 3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Glenn (1984-09-12). "Jerry Voorhis, '46 Nixon foe" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-20. (subscription required)

- Jordan, Frank (1946). "Primary Election, June 4, 1946". State of California Statement of Vote. California State Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Ex-Rep. Hoeppel, veterans affairs activist, dies at 95". The Los Angeles Times. 1976-09-22. Retrieved 2009-07-21. (subscription required)

- Lydon, Christopher (1974-01-31). "Murray Chotiner, Nixon mentor dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-13. (subscription required)

- "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2009-08-22. (Consumer bundle)

- "Dexter seems favored by Republicans". Monrovia News Post. 1945-10-06. p. 1.

- Seelye, Howard (1971-07-21). "Voorhis recalls Nixon's entry into politics" (PDF). The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-07-21. (subscription required)

- "New faces in the House". Time. 1946-11-18. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- Voorhis, Jerry (1945-10-15). "October 15, 1945 letter to Charles B. Voorhis". Box 109, Voorhis archives. Hannold-Mudd Library, Claremont, CA.

- Voorhis, Jerry (1946-03-27). "March 27, 1946 letter to V. R. (Jack) Long". Box 30, Voorhis archives. Hannold-Mudd Library, Claremont, CA.

rev_(cropped).jpg)