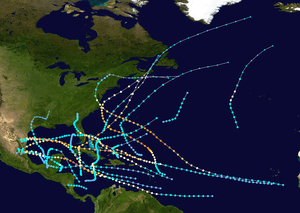

1933 Cuba–Bahamas hurricane

The 1933 Cuba–Bahamas hurricane was last of six major hurricanes, or at least a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale,[nb 1] in the active 1933 Atlantic hurricane season. It formed on October 1 in the Caribbean Sea as the seventeenth tropical storm, and initially moved slowly to the north. While passing west of Jamaica, the storm damaged banana plantations and killed one person. On October 3, the storm became a hurricane, and the next day crossed western Cuba. Advance warning in the country prevented any storm-related fatalities, although four people suspected of looting were shot and killed during a curfew in Havana. The German travel writer Richard Katz witnessed the hurricane while in Havana, and described the experience in his book "Loafing Around the Globe" ("Ein Bummel um Die Welt").[3]

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

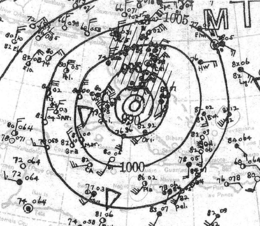

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane near Florida on October 5 | |

| Formed | October 1, 1933 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 9, 1933 |

| (Extratropical after October 8, 1933) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 125 mph (205 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 958 mbar (hPa); 28.29 inHg |

| Fatalities | 10 direct |

| Damage | $1.1 million (1933 USD) |

| Areas affected | Nicaragua, Honduras, Jamaica, Cuba, Florida, The Bahamas, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season | |

After entering the Florida Straits, the hurricane turned to the northeast, producing tropical storm winds along the Florida Keys. High rainfall caused flooding, while three tornadoes spawned by the storm damaged houses in the Miami area. The hurricane reached peak winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) on October 6 while moving through the Bahamas. It subsequently weakened and became extratropical on October 8. The former hurricane lashed the coast of Nova Scotia with high winds and rain, leaving about $1 million (1933 CAD) in damage. Rough seas sank several ships and killed nine people in the region. The remnants of the hurricane eventually dissipated on October 9 to the south of Newfoundland.

Meteorological history

Toward the end of September 1933, there was a large area of disturbed weather across the southern Caribbean Sea.[4] By September 30, a low pressure area developed south of San Andrés island. The next day, observations from a station at Cabo Gracias a Dios and a ship indicated a tropical storm had developed off the eastern coast of Honduras. Low atmospheric pressure suggested the system had winds of tropical storm force despite lack of direct observations. Moving northward, the storm gained size as it slowly intensified. Based on observations and interpolation of data, it is estimated the storm became a hurricane early on October 3 while passing west of Jamaica.[5] That day, a station at South Negril Point that day reported a force 8 on the Beaufort scale, well to the east of the center.[4] While approaching the southern coast of Cuba, the hurricane reached estimated winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[5] At 0900 UTC on October 4, the hurricane made landfall on the Zapata Peninsula of Cuba, followed by a second landfall on the Cuban mainland three hours later. Beginning at 1600 UTC that day, the capital, Havana, observed the passage of the eye, where a pressure of 976 mbar (28.8 inHg) was reported.[5]

The hurricane weakened slightly over land before emerging into the Straits of Florida and re-intensifying. On October 5, it turned to the northeast while remaining southeast of the Florida mainland, although the strongest winds remained over water. Early on October 6 while the hurricane was moving through the Bahamas, a ship reported a pressure of 958 mbar (28.3 inHg), although it was unknown if it was in the center or the periphery of the storm. Based on the data, the maximum sustained winds were estimated at 125 mph (205 km/h), although the ship estimated winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). The storm maintained peak winds for about 18 hours, after which it weakened while accelerating to the northeast. After passing to the west of Bermuda on October 7, the hurricane became extratropical the next day while still maintaining hurricane-force winds. The storm brushed the coast of Nova Scotia before it was last noted approaching another extratropical storm on October 9 to the south of Atlantic Canada.[5]

Preparations and impact

Early in its duration, the developing storm brushed the coast of Honduras with light winds.[5] In Jamaica, gusts approached hurricane force, while heavy rainfall damaged transportation in Kingston. The storm wrecked small houses and damaged the local banana industry. There was one death in Jamaica.[6] The hurricane crossed western Cuba with winds estimated at 105 mph (165 km/h).[5] This prompted officials to declare a curfew for the capital in the midst of political upheaval following a coup. A newspaper described the curfew before the storm as "the most peaceful night in a week."[7] However, the government ordered soldiers in Havana to shoot anyone suspected of looting, and four looters were killed during the storm's passage.[8] Heavy associated rainfall caused rivers to overflow in three provinces, flooding low-lying areas. In Cienfuegos, the storm destroyed several houses. Offshore northern Cuba, two United States ships took shelter at the port in Matanzas due to rough seas.[9] High tides flooded the Havana waterfront up to 3 ft (0.91 m) deep,[10] and several boats sank at the city's harbor.[8] Due to advance warning and evacuations, there were no direct deaths in the country,[9] and 20 people were injured.[8]

Storm warnings were issued on the west coast of Florida to Boca Grande and on the east coast to Titusville, with hurricane warnings for the Florida Keys.[11] Although the hurricane passed just southeast of the Florida Keys, the highest winds reported in Florida were 44 mph (70 km/h) in Key West. The storm passed closest to Long Key, where winds were estimated at 63 mph (102 km/h), due to being on the weak side of the storm. Farther north, Miami reported winds of 35 mph (56 km/h).[5] Rainfall reached over 11 in (280 mm) in 24 hours in Key West.[12] There, the storm knocked over several trees and caused some power outages. Portions of the city were flooded while boats were washed ashore.[13] Elsewhere in Florida, three tornadoes were reported during the hurricane's passage. In Fort Lauderdale, a tornado injured one person, and another one in Miami knocked down four homes and injured two. The third tornado was in Hollywood, where several houses were damaged.[13][14]

Later as the hurricane moved through the Bahamas, it produced winds of 100 mph (161 km/h) at Hope Town and 91 mph (146 km/h) at Millville, both on Abaco. The outer periphery of the storm brushed Nantucket to the west with winds of 39 mph (63 km/h) and Bermuda to the east with 46 mph (75 km/h).[5]

While moving offshore Atlantic Canada, the former hurricane produced gale-force winds, peaking at 52 mph (83 km/h) in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[5] There, the storm also dropped heavy rainfall reaching 9.84 in (250 mm) over two days, including 3.6 in (90 mm) in 24 hours. Flooding covered streets in the province, causing traffic jams, and farmlands. In Annapolis Valley, the rainfall washed out a bridge while the winds damaged about one-third of the apple crop. The dam at Chocolate Lake overflowed due to the rainfall, and a dam broke in Great Village, destroying a nearby bridge. Many trees fell during the storm, resulting in power outages after some fell onto lines. Outside Nova Scotia, the storm produced winds of 51 mph (81 km/h) in Shediac, New Brunswick, where high waves left coastal damage. In Newfoundland, the storm washed out three bridges, as well as portions of roads and rails, and flooded one house. Throughout Atlantic Canada, high waves washed ashore, sank, or broke at least ten boats from their moorings, killing nine people including seven from an overturned boat sailing from Boston to Yarmouth. Overall damage in Canada was estimated at around $1 million (1933 CAD), including $250,000 in lost apple crop.[15][nb 2]

See also

- List of Florida hurricanes (1900–49)

Notes

- The Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale was developed in 1971,[1] and has been retroactively applied to the entirety of the Atlantic hurricane database.[2]

- $1 million in 1933 Canadian dollars (CAD) would be $20.5 million in 2013 CAD, adjusted for inflation figures from the Bank of Canada.[16] When converted to USD, the total would be $20.1 million as provided by the Oanda Corporation,[17] which would be about $1.1 million when adjusted for inflation to 1933.[18]

References

- Jack Williams (2005-05-17). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

- Chronological List of All Continental United States Hurricanes: 1851-2012 (Report). Hurricane Research Division. June 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- Katz, Richard (1935). Loafing Around the Globe. Great Britain: William Brendon & Son, Ltd. p. 277.

- Willis E. Hurd (October 1933). "Weather of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 61: 309–310. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..309H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<309b:nao>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1933) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- "Gale Hits Cuba: Heading for U.S." The Pittsburgh Press. United Press. 1933-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- "Gale Halts Cuba Riots". The Calgary Daily Herald. Associated Press. 1933-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- "Four Killed in Havana During Storm Looting". Lewiston Evening Journal. 1933-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- "Hurricane Dampens Cuban Strife Ardor". The Border Cities Star. United Press. 1933-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- "Looting in Havana, Storm Threatens". The Lewiston Daily Sun. United Press. 1933-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- "Florida Keys Fly Warnings of Hurricane". The Meriden Daily Journal. Associated Press. 1933-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- "Storm Moving over Atlantic". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. 1933-10-03. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- Mary O. Souder (October 1933). "Severe Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 61 (10): 319. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..319.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<319:slso>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- "Florida Coast Escapes Fury of Hurricane". Lewiston Evening Journal. Associated Press. 1933-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- Detailed Storm Impacts - 1933-18 (Report). Environment Canada. 2009-11-18. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- "Inflation Calculator". Bank of Canada. 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- "Historical Exchange Rates". Oanda Corporation. 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013). "CPI Inflation Calculator". United States Department of Labor. Retrieved 2013-10-03.