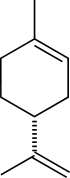

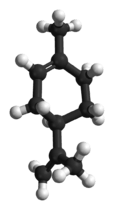

Limonene

Limonene is a colorless liquid aliphatic hydrocarbon classified as a cyclic monoterpene, and is the major component in the oil of citrus fruit peels.[1] The D-isomer, occurring more commonly in nature as the fragrance of oranges, is a flavoring agent in food manufacturing.[1][2] It is also used in chemical synthesis as a precursor to carvone and as a renewables-based solvent in cleaning products.[1] The less common L-isomer is found in mint oils and has a piny, turpentine-like odor.[1] The compound is one of the main volatile monoterpenes found in the resin of conifers, particularly in the Pinaceae, and of orange oil.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1-Methyl-4-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-1-ene | |||

| Other names

1-Methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)cyclohexene 4-Isopropenyl-1-methylcyclohexene p-Menth-1,8-diene Racemic: DL-Limonene; Dipentene | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL |

| ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.848 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H16 | |||

| Molar mass | 136.238 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | colorless to pale-yellow liquid | ||

| Odor | Orange | ||

| Density | 0.8411 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −74.35 °C (−101.83 °F; 198.80 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 176 °C (349 °F; 449 K) | ||

| Insoluble | |||

| Solubility | Miscible with benzene, chloroform, ether, CS2, and oils soluble in CCl4 | ||

Chiral rotation ([α]D) |

87–102° | ||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.4727 | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−6.128 MJ mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Skin sensitizer / Contact dermatitis – After aspiration, pulmonary oedema, pneumonitis, and death[1] | ||

| GHS pictograms |     | ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

GHS hazard statements |

H226, H304, H315, H317, H400, H410 | ||

| P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P261, P264, P272, P273, P280, P301+330+331, P302+352, P303+361+353, P304+340, P312, P333+313, P362, P370+378, P391, P403+233, P235, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 50 °C (122 °F; 323 K) | ||

| 237 °C (459 °F; 510 K) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Limonene takes its name from French limon ("lemon").[3] Limonene is a chiral molecule, and biological sources produce one enantiomer: the principal industrial source, citrus fruit, contains D-limonene ((+)-limonene), which is the (R)-enantiomer.[1] Racemic limonene is known as dipentene.[4] D-Limonene is obtained commercially from citrus fruits through two primary methods: centrifugal separation or steam distillation.

Chemical reactions

Limonene is a relatively stable monoterpene and can be distilled without decomposition, although at elevated temperatures it cracks to form isoprene.[5] It oxidizes easily in moist air to produce carveol, carvone, and limonene oxide.[1][6] With sulfur, it undergoes dehydrogenation to p-cymene.[7]

Limonene occurs commonly as the D- or (R)-enantiomer, but racemizes to dipentene at 300 °C. When warmed with mineral acid, limonene isomerizes to the conjugated diene α-terpinene (which can also easily be converted to p-cymene). Evidence for this isomerization includes the formation of Diels–Alder adducts between α-terpinene adducts and maleic anhydride.

It is possible to effect reaction at one of the double bonds selectively. Anhydrous hydrogen chloride reacts preferentially at the disubstituted alkene, whereas epoxidation with mCPBA occurs at the trisubstituted alkene.

In another synthetic method Markovnikov addition of trifluoroacetic acid followed by hydrolysis of the acetate gives terpineol.

Biosynthesis

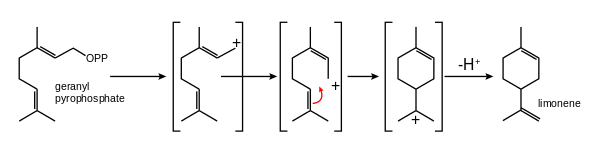

In nature, limonene is formed from geranyl pyrophosphate, via cyclization of a neryl carbocation or its equivalent as shown.[8] The final step involves loss of a proton from the cation to form the alkene.

The most widely practiced conversion of limonene is to carvone. The three-step reaction begins with the regioselective addition of nitrosyl chloride across the trisubstituted double bond. This species is then converted to the oxime with a base, and the hydroxylamine is removed to give the ketone-containing carvone.[2]

In plants

D-Limonene is a major component of the aromatic scents and resins characteristic of numerous coniferous and broadleaved trees: red and silver maple (Acer rubrum, Acer saccharinum), cottonwoods (Populus angustifolia), aspens (Populus grandidentata, Populus tremuloides) sumac (Rhus glabra), spruce (Picea spp.), various pines (e.g., Pinus echinata, Pinus ponderosa), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), larches (Larix spp.), true firs (Abies spp.), hemlocks (Tsuga spp.), cannabis (Cannabis sativa spp.),[9] cedars (Cedrus spp.), various Cupressaceae, and juniper bush (Juniperus spp.).[1] It contributes to the characteristic odor of orange peel, orange juice and other citrus fruits.[1][10] To optimize recovery of valued components from citrus peel waste, d-limonene is typically removed.[11]

Safety and research

D-Limonene applied to skin may cause irritation from contact dermatitis, but otherwise appears to be safe for human uses.[12][13] Limonene is flammable as a liquid or vapor and it is toxic to aquatic life.[1]

Uses

Limonene is common as a dietary supplement and as a fragrance ingredient for cosmetics products.[1] As the main fragrance of citrus peels, D-limonene is used in food manufacturing and some medicines, such as a flavoring to mask the bitter taste of alkaloids, and as a fragrance in perfumery, aftershave lotions, bath products, and other personal care products.[1] D-Limonene is also used as a botanical insecticide.[1][14] D-Limonene is used in the organic herbicide "Avenger".[15] It is added to cleaning products, such as hand cleansers to give a lemon or orange fragrance (see orange oil) and for its ability to dissolve oils.[1] In contrast, L-limonene has a piny, turpentine-like odor.

Limonene is used as a solvent for cleaning purposes, such as adhesive remover, or the removal of oil from machine parts, as it is produced from a renewable source (citrus essential oil, as a byproduct of orange juice manufacture).[11] It is used as a paint stripper and is also useful as a fragrant alternative to turpentine. Limonene is also used as a solvent in some model airplane glues and as a constituent in some paints. Commercial air fresheners, with air propellants, containing limonene are used by philatelists to remove self-adhesive postage stamps from envelope paper.[16]

Limonene is also used as a solvent for fused filament fabrication based 3D printing.[17] Printers can print the plastic of choice for the model, but erect supports and binders from HIPS, a polystyrene plastic that is easily soluble in limonene. As it is combustible, limonene has also been considered as a biofuel.[18]

In preparing tissues for histology or histopathology, D-limonene is often used as a less toxic substitute for xylene when clearing dehydrated specimens. Clearing agents are liquids miscible with alcohols (such as ethanol or isopropanol) and with melted paraffin wax, in which specimens are embedded to facilitate cutting of thin sections for microscopy.[19][20][21]

See also

References

- "D-Limonene". PubChem Compound Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information, US National Library of Medicine. 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Fahlbusch, Karl-Georg; Hammerschmidt, Franz-Josef; Panten, Johannes; Pickenhagen, Wilhelm; Schatkowski, Dietmar; Bauer, Kurt; Garbe, Dorothea; Surburg, Horst (2003). "Flavors and Fragrances". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- Merriam-Webster's dictionary entry for "limonene". Accessedon 2020-03-16.

- Simonsen, J. L. (1947). The Terpenes. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. OCLC 477048261.

- Pakdel, H. (2001). "Production of DL-limonene by vacuum pyrolysis of used tires". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 57: 91–107. doi:10.1016/S0165-2370(00)00136-4.

- Karlberg, Ann-Therese; Magnusson, Kerstin; Nilsson, Ulrika (1992). "Air oxidation of D-limonene (the citrus solvent) creates potent allergens". Contact Dermatitis. 26 (5): 332–340. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00129.x. PMID 1395597.

- Weitkamp, A. W. (1959). "I. The Action of Sulfur on Terpenes. The Limonene Sulfides". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 81 (13): 3430–3434. doi:10.1021/ja01522a069.

- Mann, J. C.; Hobbs, J. B.; Banthorpe, D. V.; Harborne, J. B. (1994). Natural Products: Their Chemistry and Biological Significance. Harlow, Essex: Longman Scientific & Technical. pp. 308–309. ISBN 0-582-06009-5.

- Booth, Judith K.; Page, Jonathan E.; Bohlmann, Jörg (29 March 2017). Hamberger, Björn (ed.). "Terpene synthases from Cannabis sativa". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0173911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173911. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5371325. PMID 28355238.

- Perez-Cacho, Pilar Ruiz; Rouseff, Russell L. (10 July 2008). "Fresh squeezed orange juice odor: A review". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 48 (7): 681–695. doi:10.1080/10408390701638902. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 18663618.

- Sharma, Kavita; Mahato, Neelima; Cho, Moo Hwan; Lee, Yong Rok (2017). "Converting citrus wastes into value-added products: Economic and environmentally friendly approaches". Nutrition. 34: 29–46. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2016.09.006. ISSN 0899-9007. PMID 28063510.

- Kim, Y.-W.; Kim, M.-J.; Chung, B.-Y.; Bang Du, Y.; Lim, S.-K.; Choi, S.-M.; Lim, D.-S.; Cho, M.-C.; Yoon, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, K.-B.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kwack, S.-J.; Lee, B.-M. (2013). "Safety evaluation and risk assessment of D-Limonene". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B. 16 (1): 17–38. doi:10.1080/10937404.2013.769418. PMID 23573938.

- Deza, Gustavo; García Bravo, Begoña; Silvestre, Juan F.; Pastor Nieto, Maria A.; González Pérez, Ricardo; Heras Mendaza, Felipe; Mercader, Pedro; Fernández Redondo, Virginia; Niklasson, Bo; Giménez Arnau, Ana M; GEIDAC (2017). "Contact sensitization to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides in Spain: A GEIDAC prospective study" (PDF). Contact Dermatitis. 76 (2): 74–80. doi:10.1111/cod.12714. hdl:10230/33527. PMID 27896835.

- EPA Fact Sheet on Limonene, September 1994

- Avenger Material Safety Data Sheet http://nebula.wsimg.com/07de45c0af774ba73e06362ad1a56f06?AccessKeyId=C67FD801C8FC93742D64&disposition=0&alloworigin=1

- Butler, Peter (October 2010). "It's Like Magic; Removing Self-Adhesive Stamps from Paper" (PDF). American Philatelist. American Philatelic Society. 124 (10): 910–913.

- "Using D-Limonene to Dissolve 3D Printing Support Structures". Fargo 3D Printing. 26 April 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Cyclone Power to Showcase External Combustion Engine at SAE Event, Green Car Congress, 20 September 2007

- Wynnchuk, Maria (1994). "Evaluation of Xylene Substitutes For A Paraffin Tissue Processing". Journal of Histotechnology (2): 143–149. doi:10.1179/014788894794710913.

- Carson, F. (1997). Histotechnology: A Self-Instructional Text. Chicago, IL: ASCP Press. p. 28–31. ISBN 0-89189-411-X.

- Kiernan, J. A. (2008). Histological and Histochemical Methods (4th ed.). Bloxham, Oxon. pp. 54, 57. ISBN 978-1-904842-42-2.