Nubia

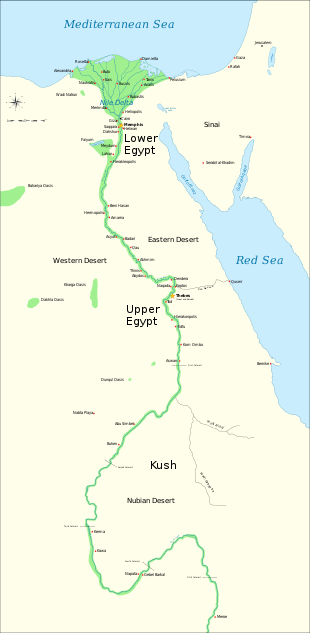

Nubia (/ˈnuːbiə, ˈnjuː-/) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt)[2][3] and the confluence of the blue and white Niles (south of Khartoum in central Sudan)[3] or, more strictly, Al Dabbah.[2][4] It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, as the Kerma culture lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt during the 8th century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its Twenty-fifth Dynasty (to be replaced a century later by the native Egyptian Twenty-sixth Dynasty).

The collapse of Kush in the 4th century AD after more than a thousand years of existence was precipitated by an invasion by Ethiopia's Kingdom of Aksum and saw the rise of three Christian kingdoms, Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia, the last two again lasting for roughly a millennium. Their eventual decline initiated not only the partition of Nubia into the northern half conquered by the Ottomans and the southern half by the Sennar sultanate in the 16th century, but also a rapid Islamization and partial Arabization of the Nubian people. Nubia was again united with the Khedivate of Egypt in the 19th century. Today, the region of Nubia is split between Egypt and Sudan.

The primarily archaeological science dealing with ancient Nubia is called Nubiology.

Linguistics

The name Nubia is derived from that of the Noba people, nomads who settled the area in the 4th century AD following the collapse of the kingdom of Meroë. The Noba spoke a Nilo-Saharan language, ancestral to Old Nubian. Old Nubian was mostly used in religious texts dating from the 8th and 15th centuries. Before the 4th century, and throughout classical antiquity, Nubia was known as Kush, or, in Classical Greek usage, included under the name Ethiopia (Aethiopia).

Historically, the people of Nubia spoke at least two varieties of the Nubian language group, a subfamily that includes Nobiin (the descendant of Old Nubian), Kenuzi-Dongola, Midob and several related varieties in the northern part of the Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan. Until at least 1970, the Birgid language was spoken north of Nyala in Darfur, but is now extinct. However, the linguistic identity of the ancient Kerma Culture of southern and central Nubia (also known as Upper Nubia), is uncertain, with some suggesting that it belonged to the Cushitic branch of Afroasiatic languages,[5][6] and other more recent research indicating that the Kerma culture instead belonged to the Eastern Sudanic branch of Nilo-Saharan languages, and that other peoples of northern (or Lower) Nubia north of Kerma (such as the C-group culture and the Blemmyes) spoke Cushitic languages before the spread of Eastern Sudanic languages from southern (or Upper) Nubia.[7][8][9][10]

Geography

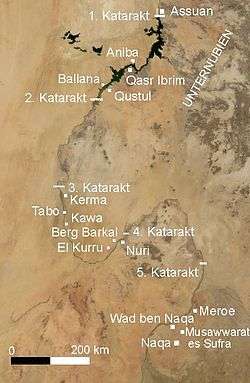

Nubia was divided into three major regions: Upper, Middle, and Lower Nubia, in reference to their locations along the Nile. Lower refers to regions downstream and upper refers to regions upstream. Lower Nubia lies between the First and the Second Cataracts, within the current borders of Egypt. Middle Nubia lies between the Second and the Third Cataracts. Upper Nubia lies south of the Third Cataract.[11]

History

Prehistory

.jpg)

Early settlements sprouted in both Upper and Lower Nubia. Egyptians referred to Nubia as "Ta-Seti," or "The Land of the Bow," since the Nubians were known to be expert archers.[12] Modern scholars typically refer to the people from this area as the "A-Group" culture. Fertile farmland just south of the Third Cataract is known as the "pre-Kerma" culture in Upper Nubia.

By the 5th millennium BC, the people who inhabited what is now called Nubia participated in the Neolithic revolution. Saharan rock reliefs depict scenes that have been thought to be suggestive of a cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Eastern Africa and the Nile Valley even to this day.[13] Megaliths discovered at Nabta Playa are early examples of what seems to be one of the world's first astronomical devices, predating Stonehenge by almost 2,000 years.[14] This complexity as observed at Nabta Playa, and as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there, likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.[15] Around 3500 BC, the second "Nubian" culture, termed the A-Group, arose.[16] The A-Group people were engaged in trade with the Egyptians. This trade is testified archaeologically by large amounts of Egyptian commodities deposited in the graves of the A-Group people. The imports consisted of gold objects, copper tools, faience amulets and beads, seals, slate palettes, stone vessels, and a variety of pots.[17]

The A-Group culture came to an end around 3100 BCE, when it was destroyed, apparently by the First Dynasty rulers of Egypt.[18]

George Reisner suggested that it was succeeded by a culture that he called the "B-Group", but most archaeologists today believe that this culture never existed and that the area was depopulated from c. 3000 BC to c. 2500 BC, when a-group descendants returned to the area.[19][20] The causes of this are uncertain, but it was perhaps caused by Egyptian invasions and pillaging that began at this time. Nubia is believed to have served as a trade corridor between Egypt and tropical Africa long before 3100 BC. Egyptian craftsmen of the period used ivory and ebony from tropical Africa, which came through Nubia.

Nubia and ancient Egypt

| Nubia in hieroglyphs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ta-seti T3-stj Curved land[21] | |||||||||

Setiu Stjw Curved land of the Nubians[22] | |||||||||

Nehset / Nehsyu / Nehsi Nḥst / Nḥsyw / Nḥsj Nubia / Nubians | |||||||||

| |||||||||

One interpretation is that Nubian A-Group rulers and early Egyptian pharaohs used related royal symbols. Similarities in rock art of A-Group Nubia and Upper Egypt support this position. Ancient Egypt conquered Nubian territory in various eras, and incorporated parts of the area into its provinces. The Nubians in turn were to conquer Egypt under its 25th Dynasty.[23]

.jpg)

However, relations between the two peoples also show peaceful cultural interchange and cooperation, including mixed marriages. The Medjay (mḏꜣ,[24]) represents the name ancient Egypt gave to a region in northern Sudan where an ancient people of Nubia inhabited. They became part of the Egyptian military as scouts and minor workers.

Scholars from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute excavated at Qustul (near Abu Simbel – Modern Sudan), in 1960–64, and found artifacts which incorporated images associated with Egyptian pharaohs. From this Williams concluded that "Egypt and Nubia A-Group culture shared the same official culture", "participated in the most complex dynastic developments", and "Nubia and Egypt were both part of the great East African substratum".[25] Williams also wrote that Qustul in Nubia "could well have been the seat of Egypt's founding dynasty".[26][27] David O'Connor wrote that the Qustul incense burner provides evidence that the A-group Nubian culture in Qustul marked the "pivotal change" from predynastic to dynastic "Egyptian monumental art".[28]

However, "most scholars do not agree with this hypothesis",[29] as more recent finds in Egypt indicate that this iconography originated in Egypt not Nubia, and that the Qustul rulers adopted/emulated the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs.[30][31][32][33][34] Moreover, There's no evidence that the pharaohs of the First dynasty buried at Abydos were of nubian origin.[35]

More recent and broader studies have determined that the distinct pottery styles, differing burial practices, different grave goods and the distribution of sites all indicate that the Naqada people and the Nubian A-Group people were from different cultures. Kathryn Bard further states that "Naqada cultural burials contain very few Nubian craft goods, which suggests that while Egyptian goods were exported to Nubia and were buried in A-Group graves, A-Group goods were of little interest further north."[36]

In 2300 BC, Nubia was first mentioned in Old Kingdom Egyptian accounts of trade missions. From Aswan, right above the First Cataract, the southern limit of Egyptian control at the time, Egyptians imported gold, incense, ebony, copper, ivory, and exotic animals from tropical Africa through Nubia. As trade between Egypt and Nubia increased, so did wealth and stability. By the Egyptian 6th dynasty, Nubia was divided into a series of small kingdoms. There is debate over whether these C-Group peoples,[37] who flourished from c. 2500 BC to c. 1500 BC, were another internal evolution or invaders. There are definite similarities between the pottery of the A-Group and C-Group, so it may be a return of the ousted Group-As, or an internal revival of lost arts. At this time, the Sahara Desert was becoming too arid to support human beings, and it is possible that there was a sudden influx of Saharan nomads. C-Group pottery is characterized by all-over incised geometric lines with white infill and impressed imitations of basketry.

During the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1640 BC), Egypt began expanding into Nubia to gain more control over the trade routes in Northern Nubia and direct access to trade with Southern Nubia. They erected a chain of forts down the Nile below the Second Cataract. These garrisons seemed to have peaceful relations with the local Nubian people, but little interaction during the period.[38] A contemporaneous but distinct culture from the C-Group was the Pan Grave culture, so-called because of their shallow graves. The Pan Graves are associated with the East bank of the Nile, but the Pan Graves and C-Group definitely interacted. Their pottery is characterized by incised lines of a more limited character than those of the C-Group, generally having interspersed undecorated spaces within the geometric schemes.

During the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, "Medjay" no longer referred to the district of Medja but to a tribe or clan of people. It is not known what happened to the district, but, after the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, it and other districts in Nubia were no longer mentioned in the written record.[39] Written accounts detail the Medjay as nomadic desert people. Over time, they were incorporated into the Egyptian army. In the army, the Medjay served as garrison troops in Egyptian fortifications in Nubia and patrolled the deserts as a kind of gendarmerie.[40] This was done in the hope of preventing their fellow Medjay tribespeople from further attacking Egyptian assets in the region.[41] Later, they were even used during Kamose's campaign against the Hyksos[42] and became instrumental in making the Egyptian state into a military power.[43]

By the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, the Medjay were an elite paramilitary police force.[41] No longer did the term refer to an ethnic group and, over time, the new meaning became synonymous with the policing occupation in general. Being an elite police force, the Medjay were often used to protect valuable areas, especially royal and religious complexes. Though they are most notable for their protection of the royal palaces and tombs in Thebes and the surrounding areas, the Medjay were known to have been used throughout Upper and Lower Egypt.

Some Egyptian pharaohs may have been of Nubian origin. Amenemhet I, founder of the 12th dynasty, "may have had a Nubian mother".[44][45] Mentuhotep II of the 11th dynasty "was quite possibly of Nubian origin".[46] However, According to Yurco, "Egyptian rulers of Nubian ancestry had become Egyptians culturally; as pharaohs, they exhibited typical Egyptian attitudes and adopted typical Egyptian policies".[47] Ahmose-Nefertari was thought by some scholars such as Martin Bernal to be of Nubian origin because of her black skin in most colored depictions of her. However, scholars such as Joyce Tyldesley, Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes, and Graciela Gestoso Singer, argued that her skin color is indicative of her role as a goddess of resurrection, since black is both the color of the fertile land of Egypt and that of the underworld.[48]:90[49][50]

The Kingdom of Cush was deeply influenced by Egyptian Culture,[51][52][53] Amun was its main god, and it used the methods of Egyptian art and writing.[54] The cultural Egyptianization of Nubia was at its highest levels at the times of both Kashta and Piye.[55] At the time of Egyptian domination of Nubia, children of elite Nubian families were sent to be educated in Egypt and then returned to Kush to be appointed in bureaucratic positions to ensure their loyalty. This Nubian elite adopted many Egyptian customs and gave their children Egyptian names, and despite the continuity of some Nubian customs and beliefs, Egyptianization dominated in ideas, practices, and iconography.[56] Nevertheless, the Kushite culture was not just an Egyptian culture in a Nubian environment. The Cushites developed their own language, which was expressed first by Egyptian hieroglyphs, then by their own, and finally with a cursive script. They worshiped the Egyptian gods but did not abandon their gods. And they buried their kings in the pyramids, but not in the Egyptian way.[57]

Cut off from Egypt after the fall of the 25th dynasty, the Egyptianized culture of Nubia grew increasingly Africanized until the accession in 45 BCE of Queen Amanishakhete. She temporarily arrested the loss of Egyptian culture, but then it continued unchecked.[58]

Kerma

From the pre-Kerma culture, the first kingdom to unify much of the region arose. The Kerma Culture, named for its presumed capital at Kerma, was one of the earliest urban centers in the Nile region[59] and spoke, either languages of the Cushitic branch[5][6] or, according to more recent research, spoke Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudanic branch.[7][8][9][10] By 1750 BC, the kings of Kerma were powerful enough to organize the labor for monumental walls and structures of mud brick. They also had rich tombs, with possessions for the afterlife and large human sacrifices. George Andrew Reisner excavated sites at Kerma and found distinctive Nubian architecture such as large tombs and palace-like structures. At one point, Kerma came very close to conquering Egypt. Egypt suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Kingdom of Kush.[60][61]

According to Davies, head of the joint British Museum and Egyptian archaeological team, the attack was so devastating that, if the Kerma forces had chosen to stay and occupy Egypt, they might have eliminated it for good and brought the nation to extinction. When Egyptian power revived under the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1532–1070 BC), Egyptians began to expand further southwards. The Egyptians destroyed Kerma's kingdom and capital and expanded the Egyptian empire to the Fourth Cataract.

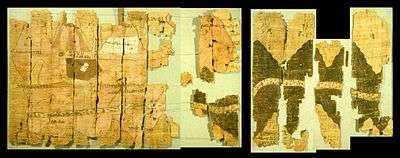

By the end of the reign of Thutmose I (1520 BC), all of northern Nubia had been annexed. The Egyptians built a new administrative center at Napata, and used the area to produce gold and incense.[62][63] The Nubian gold production made Egypt a prime source of the precious metal in the Middle East. The primitive working conditions for the slaves are recorded by Diodorus Siculus, who saw some of the mines at a later time.[64] One of the oldest maps known is of a gold mine in Nubia, the Turin Papyrus Map dating to about 1160 BC; this map is also one of the earliest characterized road maps in existence.[65]

Kush

Napatan period

_%2C_Kerma_Museum%2CSudan_(2).jpg)

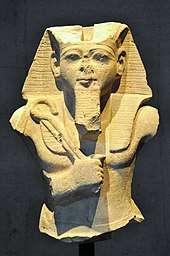

The origins of the Kushite kings of the 25th dynasty are unknown.[66] They are believed to be descended from families of the Egyptianized Nubian elite,[67][68] or possibly from Egyptian settlers or officials in Kush.[69][70] After their conquest of Egypt, "they certainly thought of themselves as Egyptians, and they began to be buried in pyramids".[70]

When the Egyptians pulled out of the Napata region, they left a lasting legacy that was merged with indigenous customs, forming the Kingdom of Kush. Archaeologists have found several burials in the area that seem to belong to local leaders. The Kushites were buried there soon after the Egyptians decolonized the Nubian frontier. The Kingdom of Kush survived longer than that of Egypt, invaded Egypt around 727 BC (under the leadership of king Piye), and controlled Egypt during the 8th century BC as the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt.[71]

The Kushites held sway over their northern neighbors for nearly 100 years, until they were eventually repelled after a long struggle by the invading Assyrians, a campaign which culminated with the Assyrian conquest of Egypt and the sack of Thebes. Although the Assyrians left Egypt immediately after their invasion, the native Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt under Psamtik I forced the Kushite permanently out of Egypt. The heirs of the Kushite empire established their capital at Napata, and later at Meroë. Of the Nubian kings of this era, Taharqa is perhaps the best known. A son and the third successor of the founding pharaoh, Piye, he was crowned in Memphis, Egypt c. 690.[72] Taharqa ruled over both Nubia and Egypt, restored Egyptian temples at Karnak, and built new temples and pyramids in Nubia before being driven from Lower Egypt by the Assyrians.[73][74][75][76]

Taharqa's successor Tantamani attempted to regain Egypt, but was chased back to Nubia. However his control over Upper Egypt endured until c. 656 BC. At this date, a native Egyptian ruler, Psamtik I son of Necho, who ruled initially as a vassal of Ashurbanipal, took control of Thebes.[77][78] The last links between Kush and Upper Egypt were severed after hostilities with the Saite kings in the 590s BC.[79]:121–122

Meroitic period

Because of continued intrigues, an Egyptian expedition sacked the capital of Kush, Napata in 592. The Kushite capital was then transferred to Meroe, where the Kushite kingdom survived for another 900 years. The Persians are believed to have tried to invade Nubia (522).[80]

Meroë (800 BC – c. 350 AD) in southern Nubia lay on the east bank of the Nile, about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, ca. 200 km north-east of Khartoum. The people there preserved many ancient Egyptian customs, but were unique in many respects. They developed their own form of writing, first utilizing Egyptian hieroglyphs, and later using an alphabetic script with 23 signs.[81] Since king Arakamani the kings were buried in Meroe.

Achaemenid period

The Achaemenids occupied the Kushan kingdom, possibly from the time of Cambyses (circa 530 BC), and more probably from the time of Darius I (550–486 BC), who mentions the conquest on Kush (Kušiya) in his inscriptions.[82][83]

Strabo describes a clash with the Roman Empire in which the Romans defeated Nubians. According to Strabo, following the Kushite advance, Gaius Petronius (a Prefect of Egypt at the time) prepared a large army and marched south. The Roman forces clashed with the Kushite armies near Thebes and forced them to retreat to Pselchis (Maharraqa) in Kushite lands. Petronius then sent deputies to the Kushites in an attempt to reach a peace agreement and make certain demands.

According to Strabo, the Kushites "desired three days for consideration" in order to make a final decision. However, after the three days, Kush did not respond and Petronius advanced with his armies and took the Kushite city of Premnis (modern Karanog) south of Maharraqa. From there, he advanced all the way south to Napata, the second Capital in Kush after Meroe. Petronius attacked and sacked Napata, causing the son of the Kushite Queen to flee. Strabo describes the defeat of the Kushites at Napata, stating that "He (Petronius) made prisoners of the inhabitants".[84]

During this time, the different parts of the region divided into smaller groups with individual leaders, or generals, each commanding small armies of mercenaries. They fought for control of what is now Nubia and its surrounding territories, leaving the entire region weak and vulnerable to attack. Meroë would eventually meet defeat by the new rising Kingdom of Aksum to their south under King Ezana.

The classification of the Meroitic language is uncertain; it was long assumed to have been one of the Afroasiatic languages like the Egyptian language, but is now considered to have likely been one of the Eastern Sudanic languages.

At some point during the 4th century AD, the region was conquered by the Noba, from which the name Nubia may derive; another possibility is that it comes from the Egyptian word for gold.[85] From then on, the Romans referred to the area as Nobatia.

Christian Nubia

Around 350 AD, the area was invaded by the Kingdom of Aksum and the Meroitic kingdom collapsed. Eventually, three smaller Christian kingdoms replaced it: northernmost was Nobatia between the first and second cataract of the Nile River, with its capital at Pachoras (modern-day Faras, Egypt); in the middle was Makuria, with its capital at Old Dongola; and southernmost was Alodia, with its capital at Soba (near Khartoum). King Silky of Nobatia crushed the Blemmyes, and recorded his victory in a Greek language inscription carved in the wall of the temple of Talmis (modern Kalabsha) around 500 AD.

While bishop Athanasius of Alexandria consecrated one Marcus as bishop of Philae before his death in 373, showing that Christianity had penetrated the region by the 4th century, John of Ephesus records that a Miaphysite priest named Julian converted the king and his nobles of Nobatia around 545. John of Ephesus also writes that the kingdom of Alodia was converted around 569. However, John of Biclarum records that the kingdom of Makuria was converted to Catholicism the same year, suggesting that John of Ephesus might be mistaken. Further doubt is cast on John's testimony by an entry in the chronicle of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria Eutychius of Alexandria, which states that in 719 the church of Nubia transferred its allegiance from the Greek to the Coptic Orthodox Church.

By the 7th century, Makuria expanded becoming the dominant power in the region. It was strong enough to halt the southern expansion of Islam after the Arabs had taken Egypt. After several failed invasions the new Muslim rulers agreed to a treaty with Dongola, called Baqt, allowing for peaceful coexistence and trade, contingent on the Nubians making an annual payment consisting of slaves and other tribute to the Islamic Governor at Aswan.[86] This treaty held for six hundred years; it also guaranteed that any runaway slaves were returned to Nubia.[87] Throughout this period, Nubia's main exports were dates and slaves,[88] though ivory and gold were also exchanged for Egyptian ceramics, textiles, and glass.[89] Over time the influx of Arab traders introduced Islam to Nubia and it gradually supplanted Christianity; furthermore, following an interruption in the annual tribute of slaves, the Egyptian Mamluk ruler invaded in 1272 and declared himself sovereign over half of Nubia.[90] While there are records of a bishop at Qasr Ibrim in 1372, his see had come to include that located at Faras. It is also clear that the cathedral of Dongola had been converted to a mosque in 1317.[91]

The influx of Arabs and Nubians to Egypt and Sudan had contributed to the suppression of the Nubian identity following the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom around 1504. A vast majority of the Nubian population is currently Muslim, and the Arabic language is their main medium of communication in addition to their indigenous Nubian language. The unique characteristic of Nubian is shown in their culture (dress, dances, traditions, and music).

Islamic Nubia

.jpg)

In the 14th century, the Dongolan government collapsed and the region became divided and dominated by Arabs. The next centuries would see several Arab invasions of the region, as well as the establishment of a number of smaller kingdoms. Northern Nubia was brought under Egyptian control, while the south came under the control of the Kingdom of Sennar in the 16th century. The entire region would come under Egyptian control during the rule of Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century, and later became a joint Anglo-Egyptian condominium.

Contemporary issues

With the end of colonialism and the establishment of the Republic of Egypt (1953), and the secession of the Republic of Sudan from unity with Egypt (1956), Nubia was divided between Egypt and Sudan.

During the early-1970s, many Egyptian and Sudanese Nubians were forcibly resettled to make room for Lake Nasser after the construction of the dams at Aswan.[92] Nubian villages can now be found north of Aswan on the west bank of the Nile and on Elephantine Island; and many Nubians now live in large cities, such as Cairo.[92]

Notes

- Elshazly, Hesham. "Kerma and the royal cache". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- Janice Kamrin; Adela Oppenheim. "The Land of Nubia". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- Raue, Dietrich (2019-06-04). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-042038-8.

- Bechaus-Gerst, Marianne; Blench, Roger (2014). Kevin MacDonald (ed.). The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography – "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. p. 453. ISBN 978-1135434168. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Behrens, Peter (1986). Libya Antiqua: Report and Papers of the Symposium Organized by Unesco in Paris, 16 to 18 January 1984 – "Language and migrations of the early Saharan cattle herders: the formation of the Berber branch". Unesco. p. 30. ISBN 9231023764. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- Rilly C (2010). "Recent Research on Meroitic, the Ancient Language of Sudan" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rilly C (January 2016). "The Wadi Howar Diaspora and its role in the spread of East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millenia BCE". Faits de Langues. 47: 151–163. doi:10.1163/19589514-047-01-900000010.

- Rilly C (2008). "Enemy brothers. Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Polish Centre for Mediterranean Archaeology. doi:10.31338/uw.9788323533269.pp.211-226. ISBN 9788323533269.

- Cooper J (2017). "Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubian placenames in the Third and Second Millenium BCE: a view from Egyptian Records". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4.

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 2, 90, 106. ISBN 9780415369886.

- Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the study of the ancient world. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- "Dr. Stuart Tyson Smith". ucsb.edu.

- PlanetQuest: The History of Astronomy – Retrieved on 2007-08-29

- Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa – by Fred Wendorf (1998)

- Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert, eds. (2002). A Dictionary of Archaeology. Wiley. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-631-23583-5.

- Hafsaas, Henriette. "Hierarchy and heterarchy – the earliest cross-cultural trade along the Nile". Connecting South and North. Sudan Studies from Bergen in Honour of Mahmoud Salih. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- "Ancient Nubia: A-Group 3800–3100 BC". The Oriental Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert, eds. (2002). A Dictionary of Archaeology. Wiley. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-631-23583-5.

- Török, László (2008). Between Two Worlds:The Frontier Region between Ancient Nubia and Egypt 3700 BC – 500AD. Brill. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9789004171978.

- Elmar Edel: Zu den Inschriften auf den Jahreszeitenreliefs der "Weltkammer" aus dem Sonnenheiligtum des Niuserre, Teil 2. In: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Nr. 5. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1964, pp. 118–119.

- Christian Leitz et al.: Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, Bd. 6: H̱-s. Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-429-1151-4, p. 697.

- Barbara Watterson, The Egyptians. Blackwell, Oxford. pp. 50–117

- Erman & Grapow, Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, 2, 186.1–2

- Williams, Bruce (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- "The Nubia Salvage Project | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". oi.uchicago.edu.

- O'Connor, David Bourke; Silverman, David P (1995). Ancient Egyptian Kingship. ISBN 978-9004100411. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- O'Connor, David (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- Shaw, Ian (2003-10-23). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. p. 63. ISBN 9780191604621. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- D. Wengrow (2006-05-25). The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa …. p. 167. ISBN 9780521835862. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- Peter Mitchell (2005). African Connections: An Archaeological Perspective on Africa and the Wider World. p. 69. ISBN 9780759102590. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- https://books.google.com/books?id%3DAR1ZZO6niVIC%26pg%3DPA194%26dq%3DQustul+burner%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DX%26ei%3DLo7-UITgFYqa0QWNnYDYDA%26ved%3D0CEcQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Qustul%20burner&f=false. Retrieved January 27, 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - László Török (2009). Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt …. p. 577. ISBN 978-9004171978. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. ISBN 9780313325014. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- Hill, Jane A. (2004). Cylinder Seal Glyptic in Predynastic Egypt and Neighboring Regions. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84171-588-9.

- An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, by Kathryn A. Bard, 2015, p. 110

- The C-Group people in Lower Nubia, 2500 – 1500 BC. Cattle pastoralists in a multicultural setting. www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- Hafsaas, Henriette. "Between Kush and Egypt: The C-Group people of Lower Nubia during the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period". Between the Cataracts. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- Gardiner, op.cit., p. 76*

- Bard, op.cit., p. 486

- Wilkinson, op.cit., p. 147

- Shaw, op.cit., p. 201

- Steindorff & Seele, op.cit., p. 28

- Bromiley, Geoffrey William (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3782-0.

- Morris, Ellen (2018-08-06). Ancient Egyptian Imperialism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-3677-8.

- Lobban, Richard A. (2003-12-09). Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6578-5.

- F. J. Yurco, "The ancient Egyptians..", Biblical Archaeology Review (Vol 15, no. 5, 1989)

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- Hodel-Hoenes, S & Warburton, D (trans), Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes, Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 268.

- Graciela Gestoso Singer, "Ahmose-Nefertari, The Woman in Black". Terrae Antiqvae, January 17, 2011

- Drury, Allen (1980). Egypt: The Eternal Smile : Reflections on a Journey. Doubleday.

- "Museums for Intercultural Dialogue - Statue of Iriketakana". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- "Cush (Kush)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- "statue | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- "Nubia | Definition, History, Map, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- Shillington, Kevin (2013-07-04). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45669-6.

- "Sudan | History, Map, Flag, Government, Religion, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- "Nubia | Definition, History, Map, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette (2009). "The Kingdom of Kush: An African Centre on the Periphery of the Bronze Age World System". Norwegian Archaeological Review. 42 (1): 50–70. doi:10.1080/00293650902978590. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- Tomb Reveals Ancient Egypt's Humiliating Secret The Times (London, 2003)

- "Elkab's hidden treasure". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15.

- James G. Cusick (5 March 2015). Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology. SIU Press. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-0-8093-3409-4.

- Richard Bulliet; Pamela Crossley; Daniel Headrick (1 January 2010). The Earth and Its Peoples. Cengage Learning. pp. 66–. ISBN 0-538-74438-3.

- Anne Burton (1973). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. BRILL. pp. 129–. ISBN 90-04-03514-1.

- James R. Akerman; Robert W. Karrow (2007). Maps: Finding Our Place in the World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-01075-5.

- Fage, John; Tordoff, with William (2013-10-23). A History of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79727-2.

- "Sudan | History, Map, Flag, Government, Religion, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- "Piye | king of Cush". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- Middleton, John (2015-06-01). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.

- Fage, John; Tordoff, with William (2013-10-23). A History of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79727-2.

- "Ancient Sudan~ Nubia: History: The Kushite Conquest of Egypt". ancientsudan.org.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- Török, László. The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: Brill, 1997. Google Scholar. Web. 20 Oct. 2011.

- Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq pp. 330–332

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 2, 75, 77–78. ISBN 9780415369886.

- "Nubia | Definition, History, Map, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- Meroë: writing – digitalegypt

- Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9004091726.

- Curtis, John; Simpson, St John (2010). The World of Achaemenid Persia: History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East. I.B.Tauris. p. 222. ISBN 9780857718013.

- Nubian Queens in the Nile Valley and Afro-Asiatic Cultural History – Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, Professor of Anthropology, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston U.S.A, August 20–26, 1998

- "Nubia". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- "Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum".

- "Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum".

- "Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum".

- "Medieval Nubia | the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago".

- "Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum".

- Hassan, Arabs, 125.

- "About Nubia". Nubian Foundation. 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

Further reading

- Adam, William Y. (1977): Nubia: Corridor to Africa, London.

- Bell, Herman (2009): Paradise Lost: Nubia before the 1964 Hijra, DAL Group.

- "Black Pharaohs", National Geographic, Feb 2008

- Bulliet et al. (2001): Nubia, The Earth and Its Peoples, pp. 70–71, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

- Drower M. (1970): Nubia A Drowning Land, London: Longmans.

- Emberling, Geoff (2011): Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World.

- Fisher, Marjorie, et al. (2012): Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile. The American University in Cairo Press.

- Hassan, Yusuf Fadl (1973): The Arabs and the Sudan, Khartoum.

- Jennings, Anne (1995) The Nubians of West Aswan: Village Women in the Midst of Change, Lynne Reinner Publishers.

- Thelwall, Robin (1978): "Lexicostatistical relations between Nubian, Daju and Dinka", Études nubiennes: colloque de Chantilly, 2–6 juillet 1975, 265–286.

- Thelwall, Robin (1982) 'Linguistic Aspects of Greater Nubian History', in Ehret, C. & Posnansky, M. (eds.) The Archeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History. Berkeley/Los Angeles, 39–56.

- Török, László (1997): The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Brill Academic Publishers.

- Valbelle, Dominique, and Bonnet, Charles (2006): The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press.

External links

![]()

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Nubia. |

- African Kingdoms

- Ancient Sudan Website

- Racism and the Rediscovery of Ancient Nubia

- Medieval Sai Project

- "Journey to Ethiopia, Eastern Sudan, and Nigritia" was written by Pierre Trémaux in 1862-63. It features extensive descriptions and drawings of Nubia.

- 1960s Nubia Scrapbook

- Nubian Foundation for Preserving a Cultural Heritage