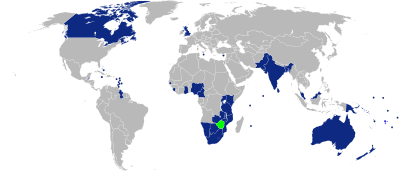

Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth of Nations

Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth of Nations have had a controversial and stormy diplomatic relationship. Zimbabwe is a former member of the Commonwealth, having withdrawn in 2003, and the issue of Zimbabwe has repeatedly taken centre stage in the Commonwealth, both since Zimbabwe's independence and as part of the British Empire.[1]

Zimbabwe was the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, gaining responsible government in 1923. Southern Rhodesia became one of the most prosperous, and heavily settled, of the UK's African colonies, with a system of white minority rule. Southern Rhodesia was integrated into the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. In response to demands for greater black African power in government, the anti-federation white nationalist Rhodesian Front (RF) was elected in 1962, leading to the collapse of federation.

The RF, under the leadership of Ian Smith from 1964, rejected the principle of NIBMAR that the Commonwealth demanded, and the Southern Rhodesian government, now styling itself 'Rhodesia', issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965. The United Kingdom refused to recognise this, and the Commonwealth was at the forefront of rejecting the UDI, imposing sanctions on Rhodesia, ending the break-away, and bringing about Rhodesia's final independence under black majority rule as Zimbabwe in 1980. However, differences of opinion of how to approach Rhodesia exposed structural and philosophical weaknesses that threatened to break-up the Commonwealth.

In recent years, under the presidency of Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe has dominated Commonwealth affairs, creating acrimonious splits in the organisation. Zimbabwe was suspended in 2002 for breaching the Harare Declaration. In 2003, when the Commonwealth refused to lift the suspension, Zimbabwe withdrew from the Commonwealth. Since then, the Commonwealth has played a major part in trying to end the political impasse and return Zimbabwe to a state of normality.

Early history

Towards responsible government

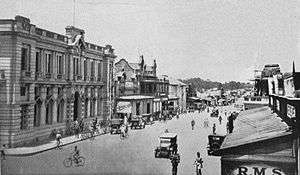

Zimbabwe was formerly known as Southern Rhodesia from 1901, having been colonised by the British South Africa Company (BSAC), headed by Cecil Rhodes. Southern Rhodesia first became a central issue in the Commonwealth in 1910, upon the creation of the Union of South Africa.[1] The South Africa Act 1909 made provisions for the accession of both Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia) to join the union. This was one of three popular options, but actively discouraged by the BSAC, which preferred union with Northern Rhodesia.[2] This was actively pursued by the BSAC administration, under Leander Starr Jameson and Francis Chaplin, as a means of countering an Afrikaner-dominated South Africa.[2]

In the election of March 1914, BSAC-supported candidates (as opposed to supporters of self-government) won twelve of the thirteen elected seats in the Legislative Council.[2] However, when the charter came up for renewal in August of the same year, it was granted only on condition that further political rights were extended: pushing the territory towards self-government.[2] Furthermore, in 1918, the Privy Council ruled that the BSAC did not own any unalienated land. Now being unable to sell land, it decided against investing any further in the colony, but advocated incorporation into South Africa, which would be able to compensate its shareholders.[2]

This, however, was unpopular amongst settlers, who, in the 1920 election, elected ten representatives of the Responsible Government Association.[2] Persuaded of its popular support, Colonial Secretary Viscount Milner formed a commission to investigate, and this commission, the Buxton Commission, ruled that the two options – union with South Africa and responsible government – be put to a referendum. Union was rejected by the Southern Rhodesian people, who voted in the 1922 referendum in favour responsible government, which was granted in 1923.[3]

A status of its own

Southern Rhodesia had been granted a great deal of autonomy, including powers over defence and constitutional amendment,[4] but falling short of dominionhood. However, observers would be forgiven for thinking that Rhodesia had just become the eighth dominion (as, indeed, reported Time magazine).[5] Southern Rhodesian Premiers were routinely invited to Imperial Conferences of dominions' Prime Ministers from 1932 onwards; and, when the Dominions Office was created in 1925, Rhodesia was the only non-dominion to fall under its remit, in recognition of its quasi-independent status.[6]

Indeed, the government of Southern Rhodesian itself was under the same misapprehension. Its official position, which it would hold until UDI, was that Southern Rhodesia was already a member of the Commonwealth, albeit not a dominion.[7] When Robert Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia, found in 1963 that Jack Howman thought that Southern Rhodesia 'is and always has been a member of the Commonwealth', this caused a diplomatic spat that contributed to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence.[7]

Nonetheless, Southern Rhodesia did recognise that it had limits on its self-government. For example, foreign relations were not maintained, nor could the government change the Southern Rhodesian pound from parity against the British pound sterling.[4] The most important derogation was on racial affairs; laws related to racial affairs were to have Royal Assent withheld.[4] However, despite these limits, and the formal supremacy of British statutes under the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865, a convention emerged that Parliament would not legislate for Southern Rhodesia, nor the Governor withhold Assent, without the Legislative Assembly's permission.[4] The threat of intervention may have achieved some successes, such as when the Rhodesian government attempted to ban native Africans from voting outright in 1934, but these were few and far between.[8] The result is that, even though self-government had been tailored to avoid the creation of a system that subjugated the native population, it happened anyway: directly against the zeitgeist of the rest of the Empire at the time.[3]

Bledisloe Commission

Discussions returned on the further integration of Southern Rhodesia with surrounding colonies. Plans to amalgamate with Northern Rhodesia had been rejected by the settler population in 1916 on the grounds that merger with its less developed neighbour would delay self-government.[3] However, when the Hilton Young Commission recommended in 1929 an even wider union, encompassing both central and eastern Africa, a Rhodesian union became the lesser of two evils, and jumped upon.[3]

In the face of this opposition to the recommendations of the Hilton Young Commission, in 1935, Viscount Bledisloe (newly departed Governor-General of New Zealand) was asked to evaluate the future of cooperation and combination of the colonies of central Africa.[9] The government required him to take into account the 'interests of the inhabitants, irrespective of race'. Taking four years to report, and acquiring the nickname 'Viscount Bloody-slow' for this, Bledisloe concluded that there was a single barrier to political integration: Southern Rhodesia's racist legislation.[9] Under the doctrine of non-interference that had been established, this was seen as insurmountable, putting off any political integration, yet allowing for the economic integration that Bledisloe recommended as feasible.[9]

Southern Rhodesia in the Second World War

Southern Rhodesia attempted to show its loyalty to, and independence of, the mother country by symbolically becoming the first colony to affirm the United Kingdom's declaration of war on Nazi Germany in 1939 (like other colonies, as well as Australia and New Zealand, which had not ratified the Statute of Westminster, it had no power to declare war itself).[4] It is often reported that a greater proportion of the population of Southern Rhodesia served in the war than of any other part of the Empire.[4] Even though this has become a part of nationalist folklore, this is to include only the White population (of whom, 15% served), and not the population as a whole (of whom, 2% served).[10] Nonetheless, there developed a nationalist perception that the UK and its empire owed the Southern Rhodesians a debt: which continued right up until the late 1970s.[10]

During the war, Southern Rhodesia benefited from the 'lucrativeness of loyalty', by hosting several bases of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Even though there were no established training facilities before the war, shortly after outbreak, Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins offered to raise three air squadrons, initiating a dialogue that led to the United Kingdom offering a blank cheque to train as many pilots and air crew as Southern Rhodesia could manage.[11] In total, 10,107 service personnel, including 7,730 pilots, were trained in Southern Rhodesia under the plan.[11] The construction and operation of the bases (paid for mostly by the UK and Canada), as well as the location of thousands of service personnel in the colony, boosted the war-time economy of Southern Rhodesia dramatically.[11] Higgins estimated that the training camps were as important to the war-time economy as the gold-mining industry.[11]

Central African Federation

Deliberations

Click here to enlarge map.

In 1945, a Central African Council was formed as a consultative body for the three British central African territories: Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland (present-day Malawi).[12] This was the limit of the British wish for integration: fearful for the same reasons Bledisloe had been. However, the conversion in July 1948 of the Northern Rhodesian settler leadership, under Roy Welensky, to supporting federalism (from long-held support for amalgamation) promoted London to reconsider its position.[12]

When Welensky held talks with the Southern Rhodesia leadership at Victoria Falls, he agreed a wide-ranging agreement that, far from loose federalism, seemed more a plot to amalgamate under white Rhodesian leadership.[12] This would be a recurring theme, firstly in April 1950, as a vicious circle of patently unacceptable Rhodesian proposals were made and flatly refused: potentially alienating the promise of resolution, hence pushing white settlers towards South Africa.[12]

The official visit of Gordon Walker to the region in early 1951 was the turning point for the United Kingdom. Startled by the strength of pro-South African support in Salisbury, Walker's report made it clear that, spurned, Southern Rhodesia could turn to outright revolt, as 'potential American colonies – very loyal, but very determined to have their own way'.[12] This, it was feared, would lead to a cataclysmic war between settler-dominated south and east Africa and native-dominated west Africa: ripping apart the nascent Commonwealth.[12] Coupled with the Baxter report from a conference of officials, the report to the cabinet stated unequivocally: "[federation is] urgently desirable in the interests of the territories (including those of the African inhabitants) and of the Commonwealth."[12]

It has been suggested that the main impetus for the British fear of South African domination of central Africa was to avoid South Africa cornering the market in various raw materials: including gold, chrome,[13] and uranium.[14]

Forming a federation

The Federation would be 'the most controversial large-scale imperial exercise in constructive state-building ever untaken by the British government'.[12]

Towards independence?

Collapse

Rhodesia after UDI

Unilateral Declaration of Independence

But for the likely hostile reaction from the rest of the Commonwealth, and hence a threat to its very existence, it is probable that the British government would have accepted an independent Southern Rhodesia upon the death of the Federation in 1963.[3] However, the preservation of the Commonwealth was the predominant concern of the British government, and thus persevered with the gradual introduction of black majority rule to Rhodesia to avoid being forced to 'choose between Southern Rhodesia and the Commonwealth' (in Harold Macmillan's words).[3]

The 1964 Meeting of Commonwealth Prime Ministers was the first held after the collapse of the federation, and, even though federal Prime Ministers had attended during federation, and Southern Rhodesian Prime Ministers had before federation, this invitation was not extended to Prime Minister Ian Smith.[3] This was seen as the utmost slight, particularly as newly independent Malawi – Southern Rhodesia's former federal partner – was in attendance. Before federation, the Southern Rhodesian government had attended every meeting since 1932, and its official position was that it was already a member of the Commonwealth, hence entitled to attend as a matter of right.[7]

On 11 November 1965, Smith issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).

Commonwealth reaction

On the day of UDI, the United Kingdom imposed the most stringent financial and economic constraints it had imposed upon any country (including Egypt during the Suez Crisis) since the Second World War.[15] In vetoing loans to Rhodesia from the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and other institutions; imposing a trade embargo on arms, sugar, and tobacco; making it harder for Rhodesians to access London financial markets than the Soviet Union; and removing Commonwealth Preference, the British government was seen to have done everything possible to punish Rhodesia economically, except to impose an oil embargo,[15] which was itself forthcoming on 17 December 1965.[16]

This was not enough to placate some Commonwealth members, who demanded a military response. Two, Ghana and Tanzania, even suspended diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom as a reaction to the United Kingdom's refusal to use military force to oust Smith.[3] An emergency Meeting of Commonwealth Prime Ministers convened in Lagos, Nigeria (the only one held outside London) on 10 January 1966 to address the crisis. At this meeting, Wilson pledged that sanctions imposed by the Commonwealth would bring the crisis to an end 'within a matter of weeks, not months'.[3] However, on 14 January, Wilson stated that military intervention could not be ruled out,[16] and, on 25 January, also stated that there would be no negotiations with the Rhodesian administration except on how to bring about an orderly return to direct rule.[16]

Negotiate or not?

The 1966 full Prime Ministers' Meeting, held in September, saw the Commonwealth as a whole close to collapse, as African members suspected that the UK was on the verge of breaking its pledges not to negotiate over the issue of NIBMAR.[3] Nonetheless, despite Harold Wilson describing it 'by common consent, the worst ever held up to that time',[17] the meeting passed without cataclysm, but led to a hiatus in PM meetings until 1969 (at the behest of Wilson, and opposed by Arnold Smith).[17] Meanwhile, the UK had been conducting exploratory talks with the Rhodesian government, aboard HMS Fearless (in 1966) and HMS Tiger (1968) that led to Rhodesia declining very favourable terms.[6] Similarly favourable terms were proposed in 1971, but discarded when the British government determined that they were largely rejected by the African population.[6]

However, this movement towards negotiation and appeasement of the Salisbury regime was turned on its head over the following two years, thanks in no small part to pressure from the Commonwealth.[3] The Singapore Declaration, issued at the first Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, articulated the political principles of the Commonwealth, including the elimination of racial discrimination.[18] With the incorporation of this implicit commitment to opposing Rhodesia into the Commonwealth's aims, and the increasingly disparity of British economic interests in Africa, the UK chose the Commonwealth over Rhodesia.[3]

Beginning of the end

The hardening of the United Kingdom's line came as part of a wave of bad news for the Rhodesian regime. The Carnation Revolution in Portugal led to the end of Portuguese assistance from Mozambique, and, in its place, put an independent Mozambique with a left-wing government, which was eager to aid guerillas from Rhodesia.[3] South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster attempted détente with the newly independent Angolan and Mozambican governments,[3] and, believing a stable majority-governed country to be in South Africa's interests, persuaded Ian Smith that white minority rule could not continue forever in Rhodesia.[6]

All this brought Rhodesia to the negotiating table with moderate African leaders, leading to the Internal Settlement under which Rhodesia became Zimbabwe Rhodesia.[6] The Commonwealth flatly refused to recognise Rhodesia-Zimbabwe, and did not lift its sanctions. At the 1979 CHOGM, the Heads of Government issued the Lusaka Declaration, once again committing itself to ending racial discrimination. The official communiqué of the meeting invited Rhodesia-Zimbabwe's new Prime Minister Abel Muzorewa and Ian Smith to a constitutional convention with the leading guerilla leaders,[19] giving rise to the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979.

Ceasefire and independence

The agreement demanded a ceasefire, reverted Rhodesia back into the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, with full control from London, and paved the way for an election in 1980. To implement the Lancaster House Agreement, at the behest of Commonwealth Secretary-General Shridath Ramphal and Kenneth Kaunda (and in the face of opposition from Lord Carrington),[20] the Commonwealth created the Commonwealth Monitoring Force (CMF). This included 1,097 Britons, as well as representatives of Australia, Canada, Fiji, Kenya, and New Zealand, totalling 1,548 service personnel.[21] They organised ceasefire assembly places, at which guerillas could disarm and reintegrate into their communities in time for the election. Observers expected the operation to fail, as the composition and swiftness of deployment seemed to fly in the face of convention wisdom.[22] Nonetheless, it succeeded in maintaining peace, demilitarising the militia and guerillas, and presiding over a peaceful election that election observers deemed free and fair.[22]

The resounding victory of Robert Mugabe's ZANU-PF in March 1980 led to Southern Rhodesia's independence as the Republic of Zimbabwe later that year. Upon independence, Zimbabwe joined the Commonwealth: five decades after Southern Rhodesia's government had mistakenly believed that it had in the wake of its invitation to the 1932 British Empire Economic Conference.[7] The end of the Rhodesian crisis was a victory for Commonwealth principles, and their application to the policies of a member: in this case, the United Kingdom itself.[3] Shridath Ramphal played a vital role in the affair, whilst it was the 1979 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting that played host to the deliberations and resolutions of the crisis, and a Commonwealth military force that kept the peace.[20]

For its part, Mozambique was recognised as a 'cousin state' of the Commonwealth,[23] and was rewarded for its opposition to the Rhodesian regime with accession to the Commonwealth in 1995: becoming the only member without direct constitutional links to another.[23]

Zimbabwe under Mugabe

Zimbabwe and the Harare Declaration

In recent times, Zimbabwe has dominated the agendas of most Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings (CHOGMs). President Robert Mugabe's government is accused of abusing human rights, rigging elections, undermining the Zimbabwean economy.[24] The matters his Government is accused of contravene the basic principles of the Commonwealth, as outlined in the Harare Declaration, issued at the 1991 CHOGM in (ironically enough)[24][25] Zimbabwe's capital, Harare.

After the Zimbabwean people rejected Mugabe's proposed new constitution in a February 2000 referendum, the situation deteriorated rapidly, as violence against opponents increased.[24] To address these issues, in September 2001, Zimbabwe sent a delegation to meet with the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG), which is responsible for upholding the Harare Declaration. Zimbabwe promised to end the violence and defend human rights, as required of them as Commonwealth members, but failed to do so. As a result, the United Kingdom pushed to suspend Zimbabwe from the Commonwealth.[24] This has been characterised by Mugabe, and South African President Thabo Mbeki, as a neo-colonial campaign, but this is derided as ungrounded revionism and racist itself.[24]

Initial 12-month suspension

The 2002 CHOGM was delayed in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States, but Zimbabwe was still top of the agenda.[1]

On 4 March 2002 the CHOGM statement issued at Coolum, Australia implicitly rejected calls by the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand for punitive action to be taken against Zimbabwe for alleged violence and intimidation surrounding the Presidential Election Campaign. CHOGM, instead, "expressed their deep concern", and called on all parties to work together "to create an atmosphere in which there could be a free and fair election". CHOGM also “noted that a Commonwealth Observer Group would report to the Commonwealth Secretary-General immediately after the Zimbabwe presidential election of 9–10 March 2002” and confirmed their agreement to:[26]

mandate the CHOGM Chairman-in-Office as well as the former and next Chairmen-in-Office [i.e. the Troika] in close consultation with the Secretary-General and taking into account the Commonwealth Observer Group Report, to determine appropriate Commonwealth action on Zimbabwe in the event the Report is adverse...which ranges from collective disapproval to suspension

Shortly after the presidential election had concluded, the Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group was submitted to the Troika.[27] Even the Government of Zimbabwe concedes that its conclusions were “adverse”. On 19 March 2002 the Troika, being the competent Commonwealth body, suspended Zimbabwe for a 12-month period. The Zimbabwe government disputes that there were legitimate grounds for its suspension. Zimbabwe considers that the CHOGM statement only permitted the Troika to go beyond an expression of collective disapproval if something adverse was reported on in the Commonwealth Observer Group Report pertaining to the period after the CHOGM statement issued and ending at the time when the voting in the election ended (7 days in total). The Zimbabwe government considers that although adverse findings were contained in the Report, none of them related to that period and therefore the Troika did not have competence to suspend it from the Commonwealth.

Purported further suspension

Unlike all other previous Commonwealth country suspensions, Zimbabwe's was for a definite period of 12 months. In the case of a suspension for a finite period there is no need for such a suspension to be lifted. It automatically lapses unless it is renewed or extended. The Zimbabwe Government and the Southern Africa Development Community contend that this therefore meant that in the absence of a renewal or extension, Zimbabwe's suspension by the Troika would automatically lapse on 19 March 2003. A split emerged in the Troika. Australia was in favour of a further suspension. South Africa and Nigeria (i.e. the majority of the Troika) were not. Indeed, the Zimbabwe Government points to the letter dated 10 February 2003 from the President of Nigeria to the Prime Minister of Australia in which he stated “that the time is now auspicious to lift sanctions on Zimbabwe with regard to her suspension from the Commonwealth Councils.” According to the Zimbabwe Government, the President of South Africa also contacted the Prime Minister of Australia to convey the same message.

Notwithstanding that there had been no Troika decision, on 12 February 2003, the Prime Minister of Australia and the Secretary General of the Commonwealth announced that Zimbabwe would remain suspended until the next CHOGM in December 2003. This “purported” further suspension was disputed by the other members of the Troika and Zimbabwe for the reasons described above. Moreover, the Southern African Development Community formally confirmed its position that Zimbabwe's one-year suspension had lapsed on 19 March 2003. This was reaffirmed at a meeting of the troika of the SADC Organ for Politics, Defence and Security — namely Lesotho (chair), Mozambique and South Africa, with Zimbabwe invited — in Pretoria in late November 2003.[28]

Final suspension and Zimbabwe’s withdrawal

Failing to get Mugabe to meet with the opposition MDC Morgan Tsvangirai, Chairperson-to-be Obasanjo refused to invite Mugabe to the CHOGM.[24]

The rest of the CHOGM's deliberations on Zimbabwe were marked by the same African disunity, foiling Mbeki's repeated attempts to have Zimbabwe readmitted. Ultimately he CHOGM rejected the Mbeki led minority group and implicitly rejected the views of the majority of the Troika that Zimbabwe's suspension had already terminated.[26] Instead, the CHOGM statement (tabled by Canada and Kenya) treated Zimbabwe as a country that was still suspended and determined to continue its suspension for an indefinite period, appointing a six-member panel to advise on the way forward. The committee, composed of the Heads of Government of South Africa, Mozambique, Nigeria, India, Jamaica, Australia, and Canada, ruled by six-to-one (South Africa being the one) against lifting Zimbabwe's suspension.[24]

Following the CHOGM, the SADC (supported by Uganda) issued a statement in which it expressed deep concern at what it called the ‘dismissive, intolerant and rigid attitude’ shown by some Commonwealth members toward Zimbabwe. SADC has consistently pleaded for greater patience and understanding of Zimbabwe, and cautioned against lecturing and hectoring.[28] A separate and not directly related matter at the CHOGM was an attempt by Mbeki to oust Secretary-General Don McKinnon,[29] who was up for election but whom convention dictated should not be challenged.[30] However, only seven (of eighteen) African Heads of Government voted for Mbeki's candidate (along with the four South Asian countries),[24] Sri Lanka's Lakshman Kadirgamar, allowing McKinnon to win by 40 votes to 11.[29]

Zimbabwe withdraws and reaction

In an official letter to the Commonwealth Secretariat dated 11 December 2003, Zimbabwe formally terminated with effect from 7 December 2003 its membership in the Commonwealth. This confirmed President Mugabe's decision to leave the organisation following the CHOGM statement issued in Nigeria, which indefinitely suspended Zimbabwe from the Commonwealth.[28] On 19 November 2003, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Zimbabwe made a detailed statement on the whole affair to the Parliament of Zimbabwe.[31]

The withdrawal marked only the third occasion (after South Africa in 1961 and Pakistan in 1971) that a country had withdrawn voluntarily, although Ireland had voluntarily declared itself a republic in 1949 thereby ending its membership.[29]

Since Zimbabwe's withdrawal

The next CHOGM, held in Abuja, Nigeria, in December 2003, was once more dominated by the Zimbabwe crisis.[32] Failing to get Mugabe to meet with the opposition MDC Morgan Tsvangirai, Chairperson-to-be Obasanjo refused to invite Mugabe to the CHOGM.[24] At the CHOGM, Mbeki attempted to oust Secretary-General Don McKinnon,[29] who was up for election but whom convention dictated should not be challenged.[30] However, only seven (of eighteen) African Heads of Government voted for Mbeki's candidate (along with the four South Asian countries),[24] Sri Lanka's Lakshman Kadirgamar, allowing McKinnon to win by 40 votes to 11.[29]

The rest of the CHOGM's deliberations on Zimbabwe were marked by the same African disunity, foiling Mbeki's repeated attempts to have Zimbabwe readmitted. To resolve the impasse, Canada and Kenya proposed a committee to resolve the issue of whether to lift Zimbabwe's suspension. The committee, composed of the Heads of Government of South Africa, Mozambique, Nigeria, India, Jamaica, Australia, and Canada, ruled by six-to-one (South Africa being the one) against lifting Zimbabwe's suspension.[24] In response, Robert Mugabe announced on 7 December that Zimbabwe was withdrawing from the Commonwealth: marking only the third occasion (after South Africa in 1961 and Pakistan in 1971) that a country had withdrawn voluntarily.[29]

British Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary David Miliband and outgoing Secretary-General Don McKinnon both expressed their approval of Zimbabwe's return to the Commonwealth if the country resolved its infringements of the Harare Declaration, especially under a new government.[33] Mugabe has stated that Zimbabwe would never rejoin the Commonwealth, calling it an 'evil organisation'.[34] Before the 2008 parliamentary election, opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, whose party won the vote,[35] announced that, under his leadership, Zimbabwe would seek a return to the Commonwealth.[36] It has been compared to South Africa's withdrawal in 1961, on the occasion of which Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker said that there would always be a 'candle in the window' until South Africa returned: the reentry of Zimbabwe would vindicate the Commonwealth's moral commitment to the Zimbabwean people and its principles.[37]

Emmerson Mnangagwa, who replaced Robert Mugabe as President of Zimbabwe in late 2017 has indicated that Zimbabwe may return to the Commonwealth in time for the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, England, following The Gambia's return to the Commonwealth under Adama Barrow on 8 February 2018, and The Gambia's return to the Commonwealth Games Federation on 31 March 2018.

On May 15, 2018, Mnangagwa submitted an application to rejoin the Commonwealth.[38]

In February 2019, Harriett Baldwin, Minister of State for Africa & International Development, said: "As of today, the UK would not be able to support this application because we don’t believe that the kinds of human rights violations that we are seeing from security forces in Zimbabwe are the kind of behaviour that you would expect to see from a Commonwealth country." In retaliation, Mnangagwa mentioned in an interview with French TV news channel France 24 that: "The Commonwealth has never told us that they are not considering our application. The view of one member is not the view of the Commonwealth".[39]

Footnotes

- "The Commonwealth at and immediately after the Coolum CHOGM". The Round Table. 91 (364): 125–9. April 2002. doi:10.1080/00358530220144139.

- Wood (2005), p. 8

- McWilliam, Michael (January 2003). "Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth". The Round Table. 92 (368): 89–98. doi:10.1080/750456746.

- Wood (2005), p. 9

- "New Dominion". Time. 24 September 1923. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- Lord Saint Brides (April 1980). "The Lessons of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia". International Security. The MIT Press. 4 (4): 177–84. doi:10.2307/2626673. JSTOR 2626673.

- Watts, Carl P. (July 2007). "Dilemmas of Intra-Commonwealth Representation during the Rhodesian Problem, 1964–65". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 45 (3): 323–44. doi:10.1080/14662040701516904.

- Louis et al. (1999), p. 552–3

- Louis et al. (1999), p. 270

- McLaughlin, Peter (July 1978). "The Thin White Line: Rhodesia's Armed Forces since the Second World War". Journal Zambezia. 6 (2): 175–88.

- Marshall, Peter (April 2000). "The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan". The Round Table. 89 (354): 267–78. doi:10.1080/750459434.

- Hyam, Ronald (March 1987). "The Geopolitical Origins of the Central African Federation: Britain, Rhodesia, and South Africa". Historical Journal. 30 (1): 145–72. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00021956.

- Gupta, Partha Sarathi (1975). Imperialism and the British Labour Movement, 1914–1964. London: Macmillan. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8419-0191-9.

- Butler, L. J. (October 2008). "The Central African Federation and Britain's Post-War Nuclear Programme: Reconsidering the Connections". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 36 (3): 509–25. doi:10.1080/03086530802318573.

- "Facing the Rhodesian Crisis". The Times. 12 November 1965. p. 13.

- "Chronology: Rhodesia UDI: Road to Settlement". London School of Economics. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Alexander, Philip (September 2006). "A Tale of Two Smiths: the Transformation of Commonwealth Policy, 1964–70". Contemporary British History. 20 (3): 303–21. doi:10.1080/13619460500407004.

- "Singapore Declaration of Commonwealth Principles 1971". Commonwealth Secretariat. 22 January 1971. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- "The Lusaka Communique, Commonwealth Heads of Government, August 1979, on Rhodesia". African Affairs. 79 (314): 115. January 1980.

- Chan, Stephen; Mudhai, Okoth F. (November 2001). "Commonwealth Residualism and the Machinations of Power in a Turbulent Zimbabwe". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 39 (3): 51–74. doi:10.1080/713999562.

- Verrier, Anthony (Winter 1994). "Peacekeeping or peacemaking? The Commonwealth Monitoring Force, Southern Rhodesia-Zimbabwe, 1979-1980". International Peacekeeping. 1 (4): 440–61. doi:10.1080/13533319408413524.

- Griffin, Stuart (November 2001). "Peacekeeping, the United Nations, and the Future Role of the Commonwealth". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 39 (3): 150–64. doi:10.1080/713999560.

- McIntyre, W. David (April 2008). "The Expansion of the Commonwealth and the Criteria for Membership". The Round Table. 97 (395): 273–85. doi:10.1080/00358530801962089.

- Taylor, Ian (July 2005). "'The Devilish Thing': The Commonwealth and Zimbabwe's Dénouement". The Round Table. 94 (380): 367–80. doi:10.1080/00358530500174630.

- Hatchard, John; Ndulo, Muna; Slinn, Peter (2004). Comparative Constitutionalism and Good Governance in the Commonwealth: an Eastern and Southern African Perspective. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-58464-7.

- The Commonwealth at the Summit – Communiques of Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings 1997 – 2005, Commonwealth Secretariat 2007

- The Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group, Commonwealth Secretariat

- SADC Barometer, January 2004 edition

- "Editorial: CHOGM 2003, Abuja, Nigeria". The Round Table. 93 (373): 3–6. January 2004. doi:10.1080/0035853042000188139.

- Baruah, Amit (7 December 2003). "PM, Blair for representative government in Iraq soon". The Hindu. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Parliament of Zimbabwe, 19 November 2003 (Hansard) Archived June 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Ingram, Derek (January 2004). "Abuja Notebook". The Round Table. 93 (373): 7–10. doi:10.1080/0035853042000188157.

- "Britain eyes Zimbabwe return to Commonwealth". Agence France-Presse. 3 April 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- "EU, the Commonwealth and Zimbabwe". Harare Tribune. 20 September 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- "Mugabe's Zanu-PF loses majority". BBC News. 3 April 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Chimakure, Constantine (28 February 2008). "Zim to rejoin Commonwealth – MDC". The Zimbabwe Independent. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Ingram, Derek (October 2007). "Twenty Commonwealth steps from Singapore to Kampala". The Round Table. 96 (392): 555–563. doi:10.1080/00358530701625877.

- "Zimbabwe applies to re-join Commonwealth, 15 years after leaving". CNN. 21 May 2018.

- "Mnangagwa lashes out over UK's stance on Commonwealth re-entry". Times Live. 11 February 2019.

References

- Wood, J.R.T. (2005). So Far and No Further!: Rhodesia's Bid for Independence During the Retreat from Empire 1959-1965. Victoria: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-4952-8.

- Louis, William Roger; Brown, Judith Margaret; Low, Alaine M.; Canny, Nicholas P.; Porter, Andrew; Marshall, Peter James; Winks, Robin W. (1999). The Oxford History of the British Empire – Volume IV: The Twentieth Century. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820564-7.